During our ominously metastasizing roundtable on R. Crumb’s Genesis, one of the big questions that kept coming up was about whether you should compare comics to other things. Is it fair to set comics next to your meatloaf and say, “You know — comics. Not so tasty”? Is it okay to put them on the wall next to a crucified copy of Kierkegaard and then complain because your cloned angst-ridden philosopher is dripping blood all over a perfectly good Walt Kelly original, and you can’t appreciate the witty swamp patois because of the agonized ratiocinating?

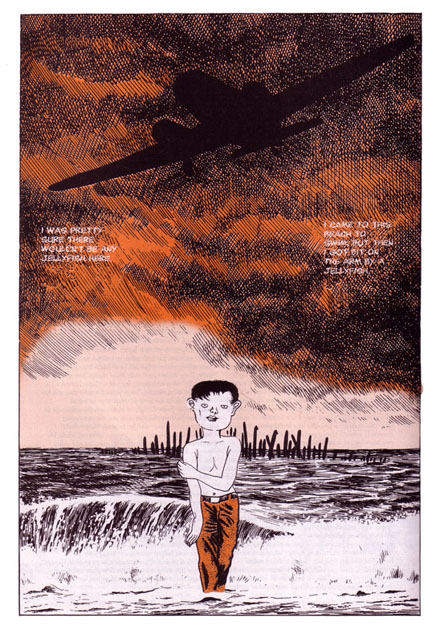

In any case, I was thinking about these issues (more or less) while reading this piece by Matt Seneca. The post focuses on a single panel from Green Lantern #171, drawn by Alex Toth.

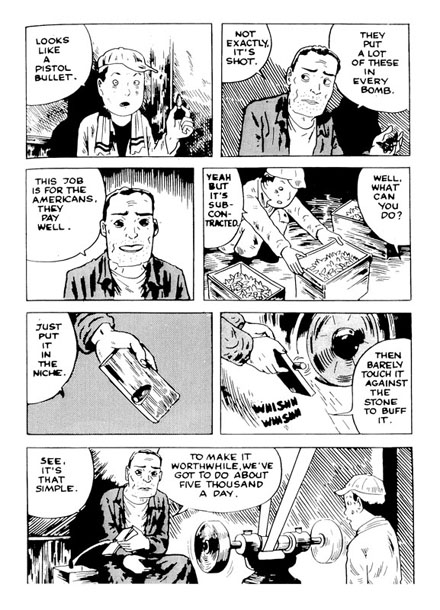

Cartooning is a white-knuckle walk down a tightrope with no end. The point of departure is illustrative drawing — the presentation of images from life, as observed in life. Plenty of artists never make it out of that realm, and as far as comics go there’s no reason why that has to be a problem. From Hal Foster to Jim Steranko, this medium has seen some fine realist artwork. But the realists ignore a fundamental challenge of the comics form: the creation of true picture-writing. Making the visuals simple and iconic enough that they carry instant meaning for the reader, with no contemplation required and no illustrative details slowing down the story. This hieroglyphic ideal is one of the more frequently stated goals of comics, I’d imagine because it separates the form from its two closest cousins, prose and illustration. Pictures that tell stories without words put comics outside the realm of the literary; and images used to inform rather than immerse fall beyond the illustrative.

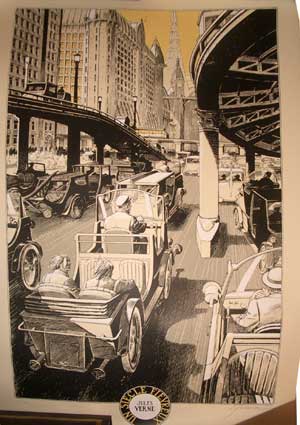

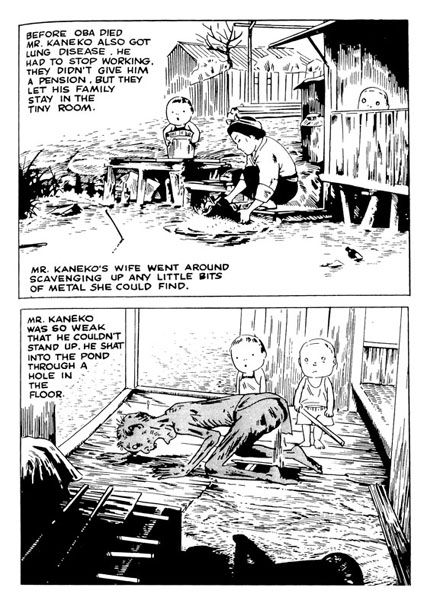

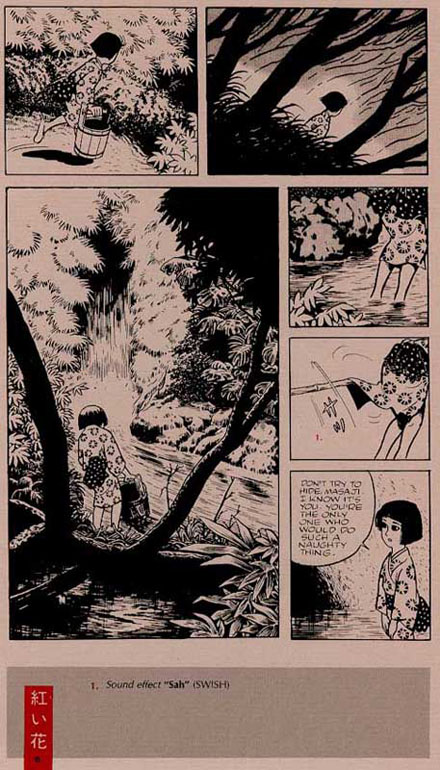

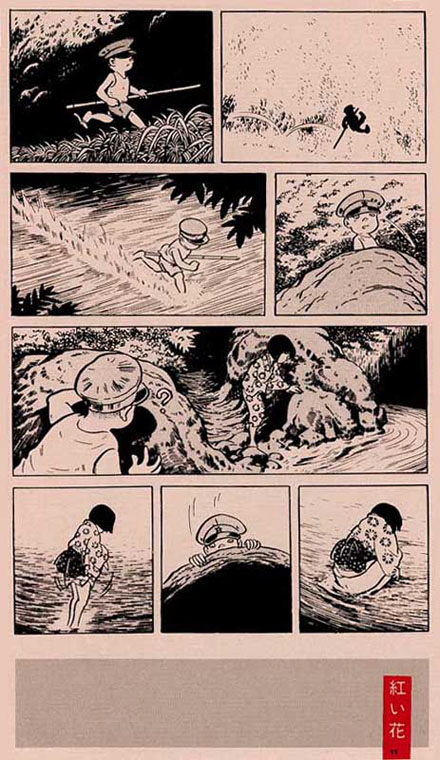

But for all the hypothetical advantages of this “ideal” mode of comics, there’s an aspect of the medium it fails to consider: the sheer beauty of illustrative artwork. Charles Schulz and Jules Feiffer, to name the two artists who’ve perhaps gotten closest to a pure-iconographic realm of comics, read better, more smoothly, than pretty much any illustrative artist you care to name. However, I personally have always found something to be missing from the experience of their work as compared to that of Alex Toth, a devoted minimalist who nonetheless took pains to keep an inoculation level of illustrative information in his panels. All three of these artists searched relentlessly to strip excess pieces from their staging, excess lines from their rendering, excess detail from their shaping of forms. But where Feiffer typically dropped his backgrounds altogether, where Schulz indicated setting with sections of rigid fence post or bits of scrubby grass, and where both essentially drew everything with the same lineweight, Toth (along with the rest of his ilk, Mignola, Crane, Yokoyama) put just enough illustrative variation into devices like line and camera angles to give his version of iconographic minimalism the added verve of pretty pictures, of the visual world’s beauty.

Seneca goes on to argue that the split here between iconic/illustrative can be mapped onto that old standby, mind/body:

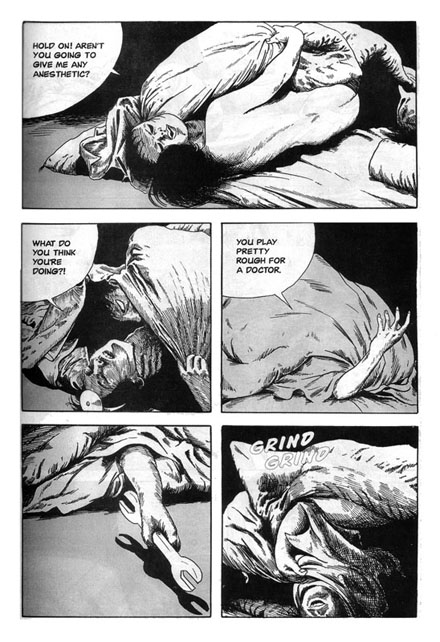

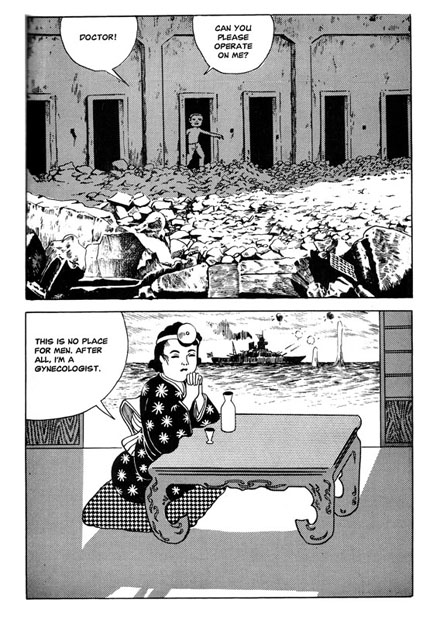

Schulz and Feiffer’s works (and those of R.O. Blechman and Ernie Bushmiller and, at times, Chris Ware) are comics of the mind, whether they be emotionally-based wanderings or dialectic ideas or even simple sight gags. But Toth drew action comics — comics of the body, of landscapes, of things that wouldn’t make sense if we couldn’t see them. This was his reason for shying away from the final pare-downs that the great strip cartoonists made: without the scraps of illustrative-comics grammar Toth employed, the environmental richness and kinetic cutting and hyperbolic figurework and variated lines, the material he drew simply wouldn’t have worked.

So, at first glance, you might say that this is an example of comparing comics to other things — specifically, the illustrative tradition.

The initial sentence, though, leads one to doubt. “Cartooning is a white-knuckle walk down a tightrope with no end.” That’s a statement of comics exceptionalism which, to me, doesn’t make a whole lot of sense unless you’re trying fairly hard not to think about other artforms. Cartooning is more white-knuckle than, say video art, which is poised between film on the one hand and the drop into television on the other? Or more of a tightrope than doom metal, poised between easy-listening fluff and the tectonic obliteration of your worthless soul? Or than performance art, poised between buckets of cow urine and tragic self parody? Any art involves difference — not that choice but this one, not this one but that one. That’s because communication and meaning are made out of difference. You might as well say asking for peas at the dinner table is a white knuckle walk, since you might slip and ask for corn or intimate sex acts instead. Indeed, Freud would actually say that (the bit about asking for peas being a white-knuckle ride, I mean, not the intimate sex acts. Though perhaps that as well, on second thought.)

Seneca then, is seeing comics as special. To do that, you need to don certain kinds of blinkers. In this case, those blinkers prevent Seneca from seeing illustration except in its relation to comics. Specifically, he argues that “The point of departure [for cartooning] is illustrative drawing — the presentation of images from life, as observed in life.” Illustration here, then, is realistic drawings meant to capture the look of life. This makes sense if you are talking about the pulp illustration that is important to the kinds of drawing Alex Toth does. It makes less sense, though, if you look at, say, this.

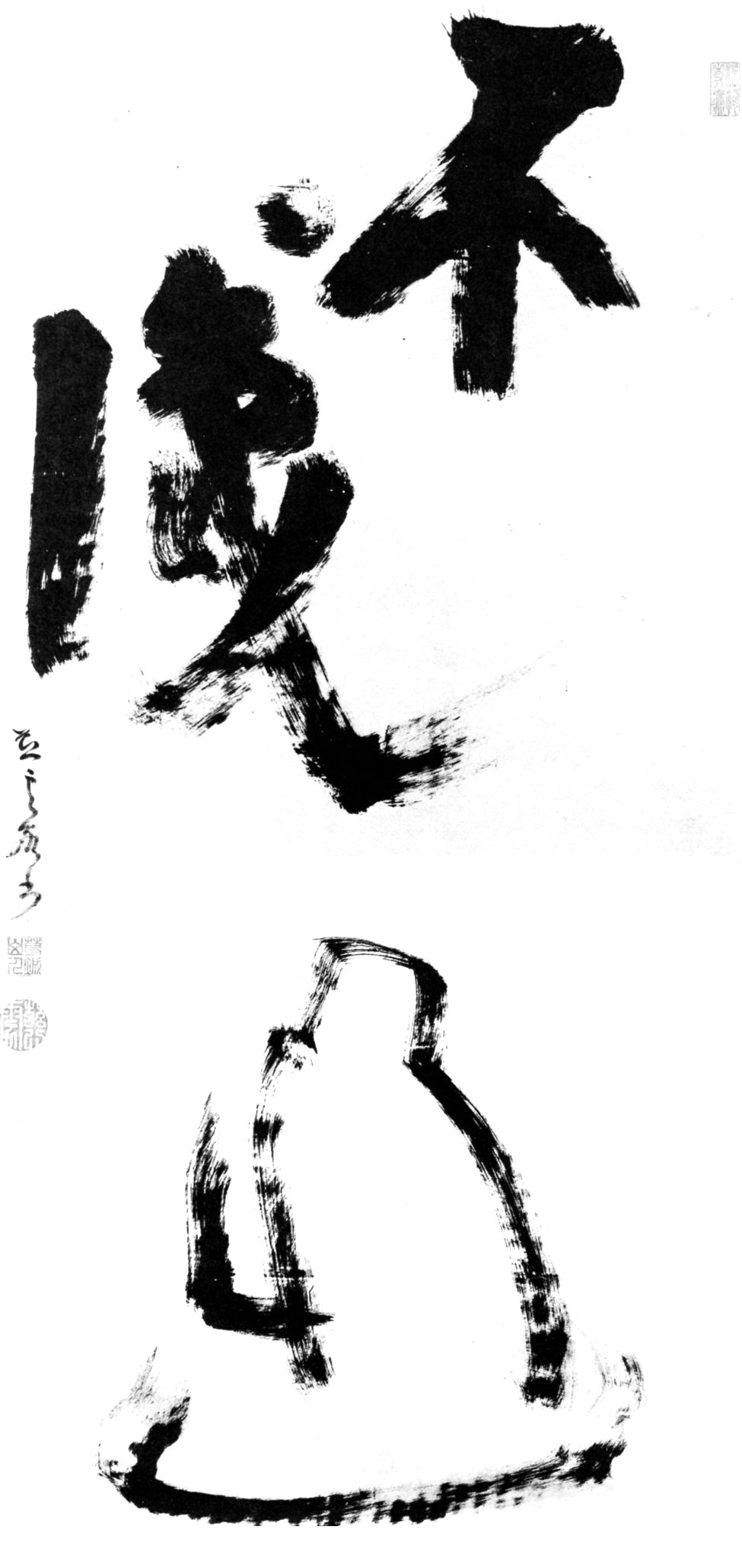

That’s an ink painting by Jiun Onko, an 18th century Buddhist priest. I wrote about it at length here. In this context, though, my point is simple…that’s an illustration.

Not only is it an illustration, but it’s a kind of illustration that is by no means marginal to the mainstream illustrative tradition. As you can see if you look at the below.

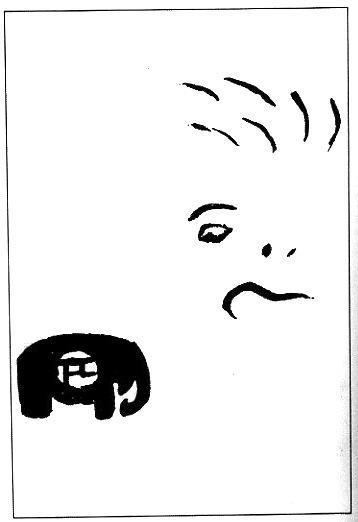

That’s Ooops! by Toulouse Lautrec, an artist who was consciously influenced by Japanese ink paintings…and whose drawings and posters, in turn, certainly seem to have been a forerunner of Toth’s style, even if they weren’t a direct influence.

So, if these are illustrations, then what does that do to the binaries Seneca has constructed?

First of all, it clearly calls into question the connection Seneca is making between illustration and realism. More than that, though, it upends the argument about the rationale for iconographic cartoons. Seneca is arguing that illustrative work is realistic and beautiful, but that cartoonists have to abandon that to make their pictures more readable. For Seneca, minimalism is chosen for ease of reading.

But if you look at the Jiun Onko and Toulouse-Lautrec drawings, it’s pretty clear that this is not a sufficient explanation. Jiun Onko, in particular, is more relentlessly iconographic than Schulz or Bushmiller; he provides less information. Indeed, he almost turns his image into a Japanese letter, or character. In that sense, his drawing is there to be “read” as Seneca suggests — but not in the interest of the sequential ease of information transmission. Rather, the image makes a connection between words, pictures, and reality — it’s an image which demands the reader/viewer/supplicant actively participate in constructing all three. Thus, the choice of an icon here is not utilitarian, but aesthetically meaningful. To draw iconically is not a default failure to incorporate the illustrative tradition. It’s an integral part of that tradition.

Drawings such as Toulouse-Lautrec’s and Jiun Onko’s also strongly call into question Seneca’s effort to make Schulz/Toth equivalent to mind/body. Look at this example of iconic artwork.

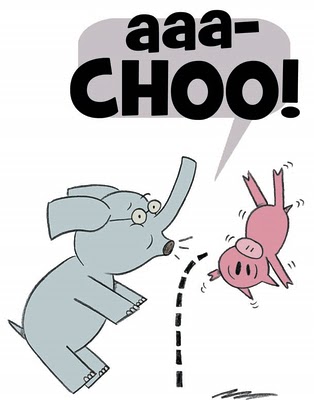

That’s a drawing by the wonderful children’s author and illustrator Mo Willems from Pigs Make Me Sneeze! Willems, as you see here, often includes dashed motion lines as part of his iconic, legible style. And what do you think my son often does when I’m reading him the book and he sees those lines?

It’s not hard to figure out; he traces them with his finger. If you look at the Toth panel up at the top there, though, nobody is going to trace that with your finger, because why would you? On the other hand, the Jiun Ito drawing or the Toulouse-Lautrec — you could see running your hand across those curves, in part because you can see the artist’s hand running across those curves. The same is true with a lot of early Peanuts; because the illustration is pared back and the linework is so instantly visible, you have the feeling of interacting directly with the hand of the creator.

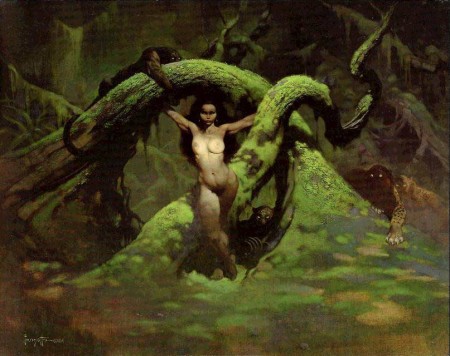

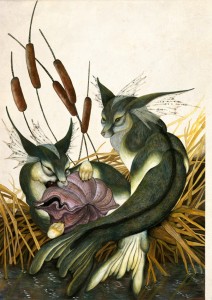

On the other hand, slick illustrational work tends to place the viewer as an onlooker, rather than pulling you in for interaction. Take a drawing like Frazetta’s Cat Girl:

You are placed as voyeur; the flesh is on display. The image is a window, the surface the line between two separate worlds rather than the place where the creator and the viewer meet. In this sense, realism can be seen not as body, but rather as body exiled to mind, while the more iconic illustrational style can be seen as mind manifested, or embodied.

The point here isn’t that Schulz and Bushmiller are better artists than Toth, or that iconic is better than realism in illustration or cartoons. Realism can be great; I like Vermeer excessively, as just one for instance. But…well, here’s Seneca’s conclusion.

What’s illustrative is how much of this environment Toth sees, the amount of visual information packed into the panel borders, the panoramic shape of the frame itself. Toth gets to his place of realness, of beauty, by piling it on, adding subtraction to subtraction to abstraction until his minimal world holds as much as the real. As much shadow, as much light, as much texture, as much scope. It’s just arranged more subtly, seen more poetically, changed into something both familiar and strikingly different. It’s art, to make it simple.

Obviously, I disagree that illustration must mean a great deal of information. I also question the parallel made in the phrase “his place of realness, of beauty”, as if realness and beauty are one and the same thing. But the real (as it were) disagreement is that Seneca equates art with muchness. What’s great about Toth is that there is “as much shadow, as much light, as much texture, as much scope” as in reality. Moreover, this muchness is arranged even more muchly than in the world — “more subtly…more poetically…both familiar and strikingly different.” Toth’s art is about getting the whole world and magically turning less into more.

Surely, though, art’s beauty is as much about curtailment as replication; as much about emptying creation as filling it. The minimal is not beautiful because it manages to get all the essential and arrange it better; it is beautiful because of its absences. What makes that Toth illustration art is not that it gives us the big world sensitively arranged, nor that it fools the eye by packing in more than can possibly be there. Rather, the art is that it doesn’t fool the eye. Instead, the blocky shapes, the distant silhouettes, encourage us to participate in pulling something out of everything — the pleasurable act of creation, which is also the act of subtraction.

So now, having disagreed with everything Seneca said, I should, in theory, conclude by lambasting him for his too narrow vision; for relating comics only to comics, and so being confused about the nature of comics, of illustration, and of art. I’m not going to do that though because — well, I’ve just been praising subtraction, haven’t I? Seneca takes a small bit of the world, turns it over, cuts it down, and ends up with a panel of flatter, more circumscribed reality. The pleasure or art in his piece is not dependent on that flatter world including the whole of the real world. Rather, the beauty is in watching and engaging with the mind that moves within the arbitrary parameters. As I suspect Seneca would agree, the point is not just what you manage to include within the lines you draw, but how you draw them.