Those of us who have made a commitment to popular culture are inevitably faced with a choice—to take a bit of entertainment at its face value, ignoring or discarding the aspects we find problematic, or to reimagine, rework or otherwise engage with the raw material to make it relevant to ourselves and our experiences. English-language comic book or television fans from virtually any time other than the past decade or so will be well-acquainted with this conundrum.

Bewitched, that sixties stalwart of witchery and sexual politics, is no exception to this dilemma. For those not in the know, the show is a 1964 situation-comedy about a witch of almost boundless power that willingly submits to life as a mortal to please her new husband. I’ve recently been rewatching the first season with Joy DeLyria, whose not-so-favorable appraisal of the show is heavy in omission and metaphor. And there’s plenty of metaphorical territory to be mined– Samantha’s inherited magical powers and other-ness could conceivably be stand-ins for a whole host of perceived problems; perhaps Samantha is Jewish, or Catholic, or is a Communist, or possesses an advanced degree, or some other similarly distancing and disturbing fact that must be hidden from the neighbors. But to look at the show’s premise metaphorically is to deny the deliciousness of the high-concept conceit itself—the delight of the metaphor made literal.

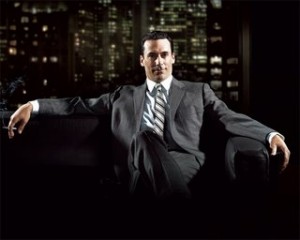

As Joy suggests, Bewitched is so thorough in its concept that invoking magical powers is hardly needed to suggest Samantha’s superiority to Darrin. She is literally, demonstrably, smarter, more attractive, more worldly and experienced, and even more creative than her bumbling, ineffectual husband, who, we are told, is a successful creative man at a fairly successful ad agency. (The evidence on the ground, however, is weak—some anemically rendered, under-realized concept sketches for campaigns that Pete Campbell himself would laugh out of a meeting room).

Samantha’s mother Endora effectively extends this argument for womanly superiority. Like her daughter, Endora is witty, intelligent, broadly skilled, and almost painfully attractive. Unlike her daughter, though, Endora is self-actualized, having taken her skills and self-assurance and tempered them in the crucible of independence. Endora does as she pleases, how and when she pleases, and with whom she pleases, for as long as it should please her. It’s this fierce, dangerous unpredictability that makes her a threat to the ineffectual Darrin, and to the social structure in which her daughter has chosen to play, if only for a little while.

And although it does so in a hesitant way, episodes of the show are not above teasing out some of the implications of the premise, including the radical concept that two beings with such powers and such long lives might look upon human beings in the way that humans do dogs — as animals that we have aligned ourselves with, are capable of having regard and even affection for, but will never truly see as equals. The show implies in several episodes that Endora is at least several millenia old, and that Samantha is already several hundred years old herself. Her husband, this man who desires normalcy so strongly that he will deny his wife her true self and the full realization of her abilities, and will even deny himself the luxury and power her skills might bring them, will himself age, quickly, gracelessly, a time-lapse photo, a blurry imitation of life compared to the richness of experience and pleasure that awaits Samantha. How can she possibly love this may-fly, this transitory creature, this animal that says so much and thinks so little? The only conclusion that is possible, a conclusion only occasionally made explicit in the show, is that Samantha is playing at being a human, not the way that a little boy and girl might play house with aprons and plastic food and furniture, rehearsing their future worlds, but the way an Olympic athlete might sit in on a pickup game of basketball, or an acclaimed novelist might pen some ad copy for her church potluck. And if Daren lives until he’s eighty, well, what’s fifty years to someone that will live for millennia? Samantha can be patient with all of Darrin’s whims, with his insecurities and his need to control every aspect of her action, because it’s part of the game of being human.

It is at this extreme that a metaphorical take on the show necessarily breaks down. Samantha might evoke the plight of intelligent, capable women of the early sixties and the lengths they had to go to conceal their true selves from their husbands, and cultures, but she’ll never literally be that woman. Samantha is ultimately safe from censure, from the consequences of the culture around her, even safe from physical harm, because of her magical powers.

At this point a different kind of literalist than myself might invoke intention. “The show’s not on their side!” this contrarian might insist. “Listen to the laugh track. Endora’s supposed to be funny, not right. She’s a caricature of the nightmare mother-in-law.” And while I’d have to concede that, yes, the presentation of the show can be problematic, I would argue that what a show seems to be saying through its laugh track, through its cinematography, is not necessarily the only thing it is saying. Some of this (mostly unrealized) potential for nuance is due to the writing, which can be quite sympathetic to the characters, but a great deal of it seems to rest on, and perhaps be inspired by, the outstanding performances of Elizabeth Montgomery as Samantha and the remarkable Agnes Moorehead, who positively sparkles as the noctiluminescent Endora. It doesn’t matter how you cut your footage or mix your laugh track– in a scene between Darrin and Endora, Darrin will forever be the bloodless, schlubby husband, Endora the preening, confident cat, a goddess in a world of garbage.

The Mad Men comparison is natural due primarily to Bewitched‘s setting and Darrin’s job as an ad man—the comparison is also instructive. It would be interesting to see what the unflinching eye of Mad Men would make of Darrin and Samantha’s relationship, what other consequences could be teased out of Samantha’s forfeiture of her powers. What would a merger of Sterling, Cooper, Draper, Price and McMann and Tate look like? How would Don Draper react to Samantha? His physical reaction is self-evident, but in addition to his much-remarked interest in the female form, he has a track record of recognition of the unrecognized, an ability to ferret out the abilities of others, and, when it is in his own interests to do so, help those others develop those abilities. But what would he make of a woman truly more than his equal, not only blessed with intelligence and insight and grace, but magical powers as well?

As for Samantha’s reaction to Don, I have no doubt she would have little interest in him, just as she shows little interest in her mother’s offers of setting her up with “some nice warlock”. Don is, after all, not unlike the warlocks we see on the show, in his arrogance, his swagger. It’s the arrogance that comes with true, unchallenged superiority, with having won every battle for a very long time; of being a god among the mortals.

No, Samantha would be content to do as she’s always done since she began to play in the sandbox of the flesh and blood—she would continue to love and care for her controlling, but doting husband, to play by his rules, in letter if not in spirit, for as long as he lives, caring for and condescending to him until he dies, at which point she can return once more to her mother, to her freedom, the world of the unbound.

I am named after “Darrin” spelled “Darren”

Samantha is perfect.

Don had a habit of being attracted to a lot of fairly strong, independent-minded women/potential mistresses throughout Mad Men, and a lot of them ended up dumping him in the end. I think he liked the challenge of trying to conquer something he can’t, or attain something unattainable. So yeah, I think he would have chased Samantha, with the same result occurring as with the rest of the other mistresses. Although, Samantha would never cheat on Darrin. The thing is, she does have a sort of virginal purity to her persona–despite her vast powers–that made her so appealing to a broad audience of that show’s time period.

The fact that Samantha had a child with Darrin later in the show works against this reading. You wouldn’t choose to reproduce with an animal.

I haven’t seen the show, so I’m at something of a disadvantage…but it strikes me that your reading fits some standard male fantasy tropes, Sean. The ugly guy/gorgeous woman meme is pretty widespread; there’s definitely a cultural button for guys about imagining themselves with someone way out of their league in terms of beauty or even power. In this case, you could see it as an Oedipal fantasy too, especially given the age discrepancy you emphasize.

Samantha slumming also makes me think of Wonder Woman slumming; throwing aside her power to be with/serve Steve. Steve openly admires WW’s power, though, whereas this seems more furtive/ambivalent.

Pallas- If you’ve committed yourself to living as a human being, I don’t see why one wouldn’t want to fully experience all that human life has to offer, and that would inevitably include children. Hell, the Greek Gods did it all the time as well-there’s precedence!

Noah, you should really watch an episode or two–first season, that is. I can’t vouch for the entertainment value of anything beyond there, at least not yet, and even then I’d say it’s about 50/50 hit and miss. Though the gender relations have to be seen to be believed. Joy and I have both, conveniently, left out Samantha’s next door neighbor, Glades Cravitz, who is convinced by circumstance and back luck, over and over again, that she’s hallucinating the various magical things happening around her, and thus is force fed her “medicine” from a bottle that her husband keeps at the ready for those occasions. No, really.

I can’t believe I’m writing this, but I always filtered Bewitched through class as opposed to gender. Samantha, as I saw her, was a part of the idle rich. She could have everything she ever wanted when she wanted it. Like the gentry of yore, talking about work was considered vulgar. Having to work was not something they could get their minds around.

The result of this metaphorical wealth for Samantha was she was bored. By marrying a mortal (my romantic nature wants me to believe she did love him, she just wasn’t slumming) her choices have real consequence. By not getting everything she wants, and having to sacrifice and work, what she works for becomes so much precious to her.

If you look at her other relatives, Uncle Arthur – a practical joke-playing buffoon, or cousin Serena – someone with the attention span of a goldfish, or her father, a pompous windbag forever boasting about how he knew William Shakespeare, you get the sense of people doing things just to keep themselves occupied. Their main goals in life seemed to be about killing boredom, not building or creating. I always got the impressin that father Maurice envied the mortal playwrights he always quoted. It was they who had a kind of magic and power of creation that he didn’t have.

Having said that, even as a kid, I recognized that Darren really needed to lighten up. But with Dick York, you really saw the insecurity come through. He was really scared that his great wife would someday come to her senses and leave him. Still he’s a bit of a control freak and if the show were to be remade today, his character would be the one who would have to really be rewritten.

I always got the impression that Samantha was enchanted with the mortal world and sincerely enjoyed living the life, which is something no one else in her family could even comprehend, let alone respect.

On the other hand, maybe it was just a kids’ show where the writers had to come up with 32 episodes a year and thus did a lot of tapdancing.

Jim–thanks for the comment!

I think that’s a valid, and defensible, interpretation, although perhaps a little less so from the point in the series from which I’m standing, about 25 episodes into the first season. So far we’ve only met Samantha’s mother, briefly her father, and her aunties, who seemed like caricatures of eccentric old women to me, rather than any coherent statement. That being said, there’s definitely an element of that–Samantha explaining to Endora that shopping, and limits, can be fun.

As for this– >>On the other hand, maybe it was just a kids’ show where the writers had to come up with 32 episodes a year and thus did a lot of tapdancing.>>>>

I hinted at this in the article–that the types of games we’re capable of playing with this material, whether metaphorical or literal, criticism or fan-fiction, which is in itself a kind of criticism, are the result of both the strength of the premise, and the poor way the thing itself is constructed. In other words, I have an impulse to write and restructure the show because the show itself doesn’t live up to its promise, because the concepts themselves are so rich but generally, are so shallowly treated. So I would make the argument that those 32 episodes a year, combined with sometimes indifferent writing and the aforementioned tapdancing, all contribute to our ability to hold multiple defensible views of the material.

Just a thought, anyway. Not yet sure if it is defensible!

@Sean Michael Robinson

Defensible or not, the article’s opening sentence and your post give me some good quotes to use for explaining my own position regarding certain pop culture artifacts. Thanks!

Cuc- Thanks! That’s great to hear. I have a kind of complicated relationship with pop media myself. On one hand, there’s so many decisions that are obviously driven by marketing strategies and the like that it’s hard to ascribe any kind of intentionality to a television program or big-budget movie. On the other hand, that lack of intentionality, once accepted, can be very freeing for reorganizing and reinterpreting to taste. Of course, in a world before draconian copyright law, that kind of reworking was part of these public stories–everyone had a crack at their favorites, and the best versions survive. Not as much these days….

“that are obviously driven by marketing strategies and the like that it’s hard to ascribe any kind of intentionality to a television program”

But the marketing department surely has an intentionality too? In terms of Bewitched, corporate america certainly had an interest in keeping housewives where they were as a marketing demographic. There were tons of products organized around the mythos of the happy housewife….

Noah– yeah, you’re completely right. I should have been clearer– the oftentimes conflicting goals of all of the various hands involved in a television or movie production make it difficult to discuss intentionality in a way that one might invoke it in a discussion on a novel or some other form of art/storytelling where there are less hands involved in the process. Should have clarified! Certainly there are pop cultural works, ala Transformers, He-Man, most kids entertainment, where the commercial considerations are so naked, and so unmitigated by other intelligences, that I think it’s fair to ascribe them. But in this case, in many cases, things are so tangled that they become up for grabs again. At least, IMHO.

“The Reality of Bewitched“:

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/TheRealityofBewitched.jpg

And…

———————–

Some episodes take a backdoor approach to such topics as racism, as seen in the first season episode, “The Witches Are Out”, in which Samantha objects to Darrin’s demeaning ad portrayal of witches as ugly and deformed. Such stereotypical imagery often causes Endora and other witches to flee the country until November. “Sisters at Heart” (season 7), whose story was submitted by a tenth-grade English class, involved Tabitha altering the skin tone of herself and a black friend with coordinating polka-dots, so that people would treat them alike.

In the 1969 episode, “Tabitha’s Weekend”, when offered homemade cookies by Darrin’s mother, Endora asks, “They’re not by chance from an Alice B. Toklas recipe?” Phyllis replies, “They’re my recipe”, to which Endora retorts, “Then I’ll pass.” Toklas had been known for her recipes being laced with marijuana.

———————–

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bewitched ; which also tells about the five foreign TV versions of “Bewitched”! Including Argentinian, Russian, Japanese… (Clips from those at http://www.bewitched.net/ )

A sculpture of “Samantha at Night, in Salem: http://www.panoramio.com/photo/6272071

If the show was reworked for today, Samantha would have to juggle more as a woman. She’d still have her husband-and later child-and she’d have her home to dutifully “house keep” along with the cooking and cleaning (made easier with more household appliances). However, she’d also have a career to maintain. This career could be moderately successful, but she’d have to carefully avoid being more successful than Darrin because if she made a higher salary or was in higher position than Darrin, he’d struggle with new feelings of insecurity. She should be good at her job, but not better than her husband. This could open up a whole new season of hilarity based around her career and workplace colliding with her home responsibilities.

In essence her role as suburban wife would have gotten harder, not easier over the 47 year lapse from when the show was originally produced. Perhaps the overworked, exhausted career women with families of our generation would appreciate this humorous, yet relevant view of their positions. After all, with the advancement of females in the workplace has come a whole new level of tired.