Earlier this week, Nadim Damluji wrote a post discussing the painful Orientalism of Craig Thompson’s Habibi. Nadim sums up his argument as follows:

Wanatolia represents the poignant identity crisis at the heart of Habibi: it wants to be a fairytale and commentary on capitalism at the same time. The problem is that in sampling both genres so fluidly, Thompson breaks down the boundaries that keep the Oriental elements in the realm of make-believe. In other words, the way in which Wanatolia is portrayed as simultaneously savage and “modern” reinforces how readers conceive of the whole of the Middle East. Although Thompson is coming from a very different place, he is presenting the same logic here that stifles discourse in the United States on issues like the right to Palestinian statehood. If we are able to understand Arabs in a perpetual version of Arabian Nights, then we are able to deny them a seat at the table of “civilized discourse.”

Thompson self-consciously presents his Orientalism as a fairy-tale. Yet the fairy tale is so riveting, and his interest in the reality of the Middle East so tenuous, that he ends up perpetuating and validating the tropes he claims not to endorse. Here, as so often, what you say effectively determines what you believe rather than the other way around.

Thinking about this, I was reminded of one of Neil Gaiman’s most admired Sandman stories — Ramadan, written in the early 1990s and drawn by the great P. Craig Russell.

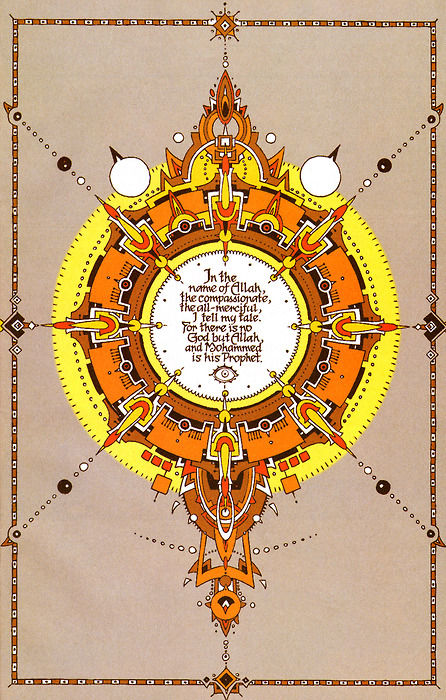

The beautiful opening page of Gaiman/Russell’s “Ramadan”.

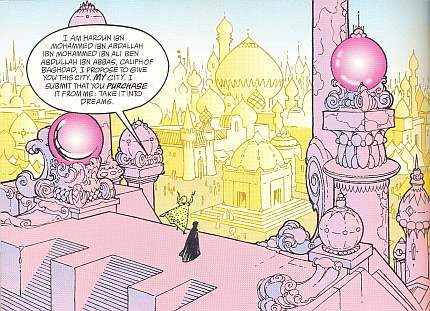

I haven’t read Thompson’s Habibi, but from Nadim’s description, it seems that Gaiman and Russell are even more explicit in treating Orientalism as a trope or fantasy. The protagonist of “Ramadan” is Haroun al Raschid, the king of Baghdad, the most marvelous city in the world. Baghdad is, in fact, the mystical distillation of all the magical stories of the mysterious East. Gaiman’s prose evokes, with varying success the exotic/poetic flourishes of Western Oriental fantasy. At his best, he captures the opulent wonder of a well-told fairy-tale:

And there was also in that room the other egg of the phoenix. (For the phoenix when its time comes to die lays two eggs, one black, one white.

From the white egg hatches the phoenix-bird itself, when its time comes.

But what hatches from the black egg no one knows.)

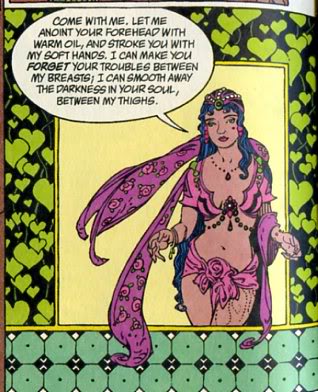

At his worst, he sounds like a sweatily clueless slam poet: there’s just no excuse for dialogue like “I can smooth away the darkness in your soul between my thighs”.

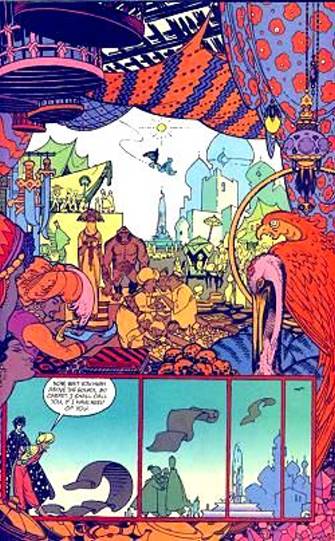

But if Gaiman’s hold on his material wavers at times, Russell makes up for any lapses. Beneath his able pen, the Arabian Nights is transformed into sweeping art nouveauish landscapes, a ravishingly familiar foreign decadence.

As I said, this is all clearly marked as fantasy — both because there are flying carpets and Phoenixes and magical globes filled with demons, and because the whole point of the narrative is that it’s a story. As the story opens, Haroun al Raschid is dissatisfied with his city, because, despite all its marvels, it will not last forever. So he makes a bargain; he will sell Baghdad to Dream, and in return Dream agrees to preserve the city forever. The bargain made, the city vanishes into dream and story. And not just the Phoenix and the magic carpet disappear, but all the marvelous wealth and luxury and wisdom of the east, from the luxurious harems to the fantastic quests. Orientalism, as it is for Craig Thompson, becomes just a story which never was.

Gaiman and Russell, then, avoid Thompson’s error; they do not conflate reality and fantasy. Fantasy is in a bottle in the dream king’s realm, forever accessible, but never actual. The real Middle East, on the other hand, must deal with a grimmer truth; the last pages of the story show Iraq as it was in the early 90s — ravaged by sanctions, brutally impoverished, and generally a gigantic mess by any objective standards (though not, of course, by the standards of the Iraq of a decade later.) In this real Iraq of starvation and misery, the other Iraq is only a dream. As Gaiman says, speaking of an Iraqi child picking his way through the ruins, “he prays…prays to Allah (who made all things) that somewhere in the darkness of dreams, abides the other Baghdad (that can never die), and the other egg of the Phoenix.”

So that’s all good then. Except…whose is this dream of Orientalism, exactly? Well, it’s the Iraqi boys, as I said, and before his, it was Haroun al Raschid’s. But really, of course, it isn’t theirs at all. It’s Gaiman and Russell’s.

Orientalism does have some roots in Arabic stories; I’m not denying that. But this particular conception of the folklore of Arabia as a single, marvelous whole, containing all that is wonderful in the East, in contrast to a sordid, depressing reality — I don’t believe Gaiman and Russell when they say that that’s a thing in the mind of Iraqis. Habin al Raschid giving up his dream is a dream itself, and the dreamer doesn’t live anywhere near Baghdad.

“Ramadan,” then, is a tale about losing a fantastic land to fantasy — but it isn’t Habin al Raschid who loses it. Rather, it’s Gaiman and Russell and you and me, (presuming you and me are Western readers.) Gaiman and Russell are, like Thompson, nostalgic for Orientalism — they know it’s a dream, a vision in a bottle, but they just can’t bear to put the bottle down. Our fantasy Middle East is so much more glamorous than the real Middle East, even the people who live there must despair that our tropes are not their reality. Surely they want to be what we want them to be, democrats or kings, sensuous harem maidens or strong independent women. Thus the magical Arabia and the sordid, debased (but potentially modern!) Arabia live on together in the world of story, comforting Western tellers with the eternal beauty of loss. Our Orient is gone. Long live our Orient.

_______________

Nadim’s thoughts have inspired an impromptu roundtable on Orientalism. which can be read here as it develops.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Jury weighs fate of Michael George | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Orientalism does have some roots in Arabic stories; I’m not denying that. But this particular conception of the folklore of Arabia as a single, marvelous whole, containing all that is wonderful in the East, in contrast to a sordid, depressing reality — I don’t believe Gaiman and Russell when they say that that’s a thing in the mind of Iraqis…

————————

Isn’t it an — if not universal, certainly widespread — phenomenon for countless cultures to have fantasies of a “golden age,” before decadence set in, when righteousness prevailed and rulers were wise and just, heroes walked the earth?

For many fundamentalist Muslims, it’s the caliphate: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caliphate .

Also, when Western media, through its massive image-making and propagating power, creates idealized images, such as those of American Indian life in “Dances With Wolves,” cannot modern Indians in the “rez” be far more moved by those fantasies, find them more appealing than actual history?

—————————

Our fantasy Middle East is so much more glamorous than the real Middle East, even the people who live there must despair that our tropes are not their reality.

—————————

Indeed so…

—————————–

Gaiman and Russell, then, avoid Thompson’s error; they do not conflate reality and fantasy.

—————————–

Yes; it makes a big difference that Russell’s art is in his more stylized mode, rather than the heavily photo-referenced “realistic” approach he’s used for stories like his adaptation of Coraline ( http://vulpeslibris.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/coraline8.jpg , http://vulpeslibris.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/coraline9.jpg ).

While Thompson said Habibi was set in “more like a fairytale landscape,” that he “was self-consciously proceeding with an embrace of Orientalism, the Western perception of the East,” “borrowing self-consciously Orientalist tropes from French Orientalist paintings and the Arabian Nights,” ( http://www.guernicamag.com/interviews/3073/thompson_interview_9_15_11/ ) the story — even in its excerpts — comes across as dramatically compelling; the characters not obvious fictions post-modernly commenting on the faux-reality of Orientalism, but full-bloodedly alive.

Thompson wanted to have his cake (the deliciously exotic fantasy image of the Orient) and eat it too (inhabit it with vividly realized characters living a powerful story). Unfortunately, that then makes the stereotypes of Orientalism seem more real, more alive…

“Isn’t it an — if not universal, certainly widespread — phenomenon for countless cultures to have fantasies of a “golden age,”

I had a similar thought, the idea of the ‘golden age’ is, as far as I’ve experienced, pretty central to post-independance rhetoric in the Middle East, the whole, “we used to be the greatest artistic/intellectual/military power in the world: what went wrong?” sort of cry.

But it doesn’t avoid the point that the dream which Gaiman portrays isn’t the Arab ‘golden age’ dream, its a quite explicitly Orientalist dream.

Its unfortunate that its the dissonance with that final section with the Iraqi boy which ruins the exercise. If that was, say a young American journalist waking up in Baghdad then ‘poof’, it becomes a critique of orientalism. Of course that might ruin the narrative a little, but still.

I find it quite interesting to wonder what this would be like as an Arab comic exploring the relationship between the ‘golden age’ dream and reality. Far more complex for a start. Its also made me wonder about how the past is portrayed (from the few issues I’ve read) in the ’99’ comics. Its nothing like as openly stereotyped as ‘Ramadan’ but the elements of magic and mysticism still feel more like orientalist tropes than actually drawn from aspects of Arab culture (such as Sufism)?

Yes; imagining a golden age would certainly be reasonable. But the idea that the golden age is a fantasy, and that deliberately choosing reality over fantasy is somehow a tragic decision — that just seems very much like a Western projection. The message seems to be that the Western dream is better than the reality, which just seems really problematic, not to mention imperialist.

I also agree with Ben that this story seems like it’s almost at a place where it could critique Orientalism, or at least question it. Treating Orientalism as a fantasy seems like a big first step in that direction. But you’d have to move to seeing the fantasy as having real-world consequences (many of them bad) rather than just expressing nostalgia for it.

Faulkner’s somebody who both has nostalgia for this kind of racist fantasy in some ways *and* who manages to see the fantasies as oppressive and causing real-world harm. Gaiman/Russell aren’t Faulkner, though….

Noah: “Gaiman/Russell aren’t Faulkner, though….”

No kidding? This Gaiman cult is yet another proof that something is really wrong with the comicsverse.

Sheesh! Making a perfectly obvious observation invoking a literary great hardly meant that Noah (not exactly a member of the Gaiman cult,” as his critique makes apparent) was saying the comics team was anywhere near Faulkner’s level.

————————-

Ben says:

…the idea of the ‘golden age’ is, as far as I’ve experienced, pretty central to post-independance rhetoric in the Middle East, the whole, “we used to be the greatest artistic/intellectual/military power in the world: what went wrong?” sort of cry.

But it doesn’t avoid the point that the dream which Gaiman portrays isn’t the Arab ‘golden age’ dream, its a quite explicitly Orientalist dream.

—————————

Certainly; but the Western media has far bigger budgets, a more global outreach. So you may end up with a situation such as my example of the idealized version of Native American life depicted in “Dances with Wolves” being possibly more appealing to modern Indians than the inescapably more drab and complex historic reality. The fictionalized past overcoming the actual past…

—————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

…But the idea that the golden age is a fantasy, and that deliberately choosing reality over fantasy is somehow a tragic decision — that just seems very much like a Western projection. The message seems to be that the Western dream is better than the reality, which just seems really problematic, not to mention imperialist.

—————————–

For sure! However, aren’t there many times where an idealized fantasy can be more inspiring to nobler behavior, better call forth “the better angels of our nature” than messy, actual history?

What would better inspire American Indian youth to admirable behavior? A reality where some Indian tribes had slaves; others hideously tortured captured enemies; where many tribes constantly warred, stole, and kidnapped women from each other; where a woman caught cheating could get her nose cut off; where rather than always being eco-minded protectors of the land, some would pull stunts like driving entire herds of bison off cliffs, just so they could more easily harvest their tasty tongues?

…Or the fictional but overwhelmingly positive image of the noble Red Man living in harmony with nature shown in well-meaning works by sympathetic Whites, or most art dealing with the Old West, for that matter?

No, I’m not suggesting that fiction is better than history; but for eliciting positive behavior, or creating inspiring images of a better future to work towards, “a spoonful of unreality helps the medicine go down”…

I think noble savage fantasies can be pretty stifling, just as angel in the house fantasies are stifling for women. Being placed on a pedestal is limiting. Having the option to be a human being, warts and all, is generally better.

Oh; re Gaiman. I do think the Sandman is pretty good. Much, much better than the Gaiman novels I’ve read, for what that’s worth.

Not much, I guess…

Well, here’s my review of Neverwhere.

Try The Wolves in the Walls. It’s a kids picture book…probably Gaiman’s best work…and it’ll only take you about 10 mins. to read.

Gaiman’s best work is a kid’s picture book which you can read in 10min? Talk about damning with faint praise.

Now, Maurice Sendak’s “best work is a kid’s picture book which you can read in 10min” (“Where the Wild Things Are”), and it’s a masterpiece!

Though I can’t say I’ve run across anything from Gaiman which grabbed me so…

———————-

eric b says:

Try The Wolves in the Walls. It’s a kids picture book…probably Gaiman’s best work…

———————

Um, not to my tastes; rather too cutesy (as Gaiman unfortunately gets fairly regularly; look at the titles of some of his stuff!).

Gaiman’s work (and the quality thereof) is all over the place; perhaps a side-effect of being as fecund as he is. I’ve far from having read a fraction of his work, though have read a lot of his comics work (never got into “Sandman,” though loving Mark Hempel’s art moved me to get the “Kindly Ones” story arc).

I do recall a pretty good “Babylon 5” episode (“Day of the Dead,” where an alien holiday brings back apparitions of deceased loved ones) and, likely his nadir, that “Marvel superheroes in Elizabethan times” thing (“Marvel 1602”)…

Certainly, in comics his “voice” is an unusual one, his approach helping him stand out. (For instance, his “Black Orchid” miniseries — his first comics work, I think — beautifully painted by Dave McKean, ends in a quiet, peaceful resolution, as would “Hold Me” years later.

A John Constantine story — “Hold Me,” art by Dave McKean (“Hellblazer” #27, 1990) — was a moving, melancholy twist on the ghost story.

“One Life Furnished in Early Moorcock” (art by P. Craig Russell, 1996) was an autobio story where, aside from telling of his youthful interest in fantasy lit, we learned of Gaiman — passed out from being asphyxiated by a schoolyard bully — lived an entire life in another world in the span of a few minutes. (Dennis Eichhorn told of his anoxia-induced hallucinatory experience, also at the hands of a school bully, in one of his comics stories)

I’ve got a couple of Gaiman novels have not got around to reading. Did buy and read his story collection “Smoke and Mirrors,” where “Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar” was an amusing take on Lovecraft, and one story, involving a Murder, Inc.-type firm hired to kill the whole world, had some genuinely creepy moments.

More info at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neil_Gaiman_bibliography .

Um, is there a more knowledgeable Gaiman fan here to adequately sing his praises?

One thing I think could be looked at is the fact that with works like this, Habibi and others based on Middle Eastern themes done by Westerners is the fact that they’re even TRYING to flesh out these characters. They might be doing it incorrectly or otherwise badly but the idea that they’re wanting to explore the culture of that part of the world in more than just a Holy Terror/Arab Henchman capacity to me is interesting.

Of course a white guy raised in the US isn’t going to fully understand Persia or the Middle East in a past or even present tense! But I think the fact that they’re trying (albeit in a misguided manner) also shows that people are trying to open up to that part of the world in some capacity. If that is really what’s going on here then I think it should be fostered and encouraged so that it can be done in a better, more informed capacity.

There’s a real problem with good intentions, though. The U.S. went into Iraq with good intentions. We were liberating them and bringing democracy, yay. If you don’t think through what you’re doing with other cultures, good intentions can lead to really bad results.

Noah, that was just the cover story for invading Iraq. It’s kind of naive (and insulting to some) to equate war and the death of thousands with art that tries to understand other cultures…no matter how flawed the art is.

It wasn’t just the cover story. Bush and co believed they were bringing democracy there. They were stupid, not (or in addition to being) Machiavellian.

Stories are stories are narratives. People tell themselves stories to explain/justify what they do, how they act, and why. Again, saying that you’re telling the stories with good intentions isn’t really the point. Everybody has good intentions. Bush had good intentions. Hitler did too. So did Rudyard Kipling and Winsor McCay when he made the imp (he was just trying to entertain people.) Good intentions don’t give you a pass for saying stupid shit.

If you believe stories matter (and you seem to, since you’re arguing that someone telling a story trying to understand another culture can be worthwhile and helpful), then that cuts both ways. He’s a high-profile cartoonist with an audience; what he says about the Middle East is part of how our culture thinks about the Middle East. Nadim thought that some of how he approached the topic was worthwhile and interesting and some was less so. But good intentions don’t mean we should focus only on the intentions and forget about the bits that are a problem. Especially since, as I said, good intentions and imperialism really have a very long and very unpleasant history together.

In terms of Gaiman and Russell — the interest in the middle east itself seems pretty tacked on; an easy way to get an ironic twist ending and some liberal heart-tugging. I don’t know; it doesn’t seem very impressive to me. They seem much more interested in the Orientalism itself, which I think they pull off with a good deal of imagination and panache. There disinterest/distaste for actual Middle Eastern people undercuts the enjoyment somewhat for me, though not entirely.

Argh; sorry, I was logged in as another user to set up a post and forgot to change. I’ve corrected things; sorry about the confusion.

I guess we’re looking at different parts here. I do agree that hinging a particular story on racial stereotypes is never good and I’m not really defending the stories in question so much as commenting on the general notion of Western artists exploring Eastern themes in what I would consider a more positive light than the “Arab Henchman/Holy Terror” type stories that have been out there for so long. Sure they messed up because they didn’t fully understand what they were working with but it’s not much different from the 80s when there were a lot of Martial Arts, ninjas and other Asian adventure themes being sprinkled in American action movies with an obvious lack of understanding of the actual culture. I think that eventually led to more authentic attempts using Asian themes (such as Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon). That’s not to say that Asians are given three dimensions in popular media these days but it’s miles above the triangle had and bucktooth characters that were all you really saw on TV and film not too long ago.

I’m not looking to excuse an artist for mishandling a subject through ignorance and bad writing but I don’t think someone should be demonized for getting a subject wrong just because we really want Middle Easterners to like us.

I still really like the idea of some academic in the field of Middle Eastern History and Orientalism is a great idea as mentioned in previous comments.

Well Noah, if that IS your real name!

Yeah; argh. Sorry about that.

I’m working on the academics. We’ll see what happens.

I don’t know that we’re disagreeing all that much. I don’t think Thompson or Gaiman/Russell should be demonized, certainly. I really like Russell’s art in general, and Gaiman has written some stories I like a lot. I think this could have worked too with some tweaking; they just didn’t manage it.

Ninjas are really interesting in this context. They’re a completely fanciful trope invented by the Japanese themselves, originally for theatrical productions, and then adopted wholesale by the U.S. (mostly through films.) So it becomes something of a shared fantasy, rather than a fantasy created by one group to explain the other, at least in some ways. (Japanese are still sort of wearisomely cast as ninjas in, say, superhero comics, of course…the fact that Westerners often imagine that ninja are somehow real (even historically) causes some weirdness also.)

I did research on ninjas a bit back, and it was actually somewhat difficult to pin down that they were just made up; popular writers in English (which was what I could read) were reluctant to come right out and say they weren’t real, and more academic writers didn’t really talk about them at all, presumably because they weren’t real and you’d look silly talking about them.

Ninjas were very real and references of them date back to 14th Century Japan, actually. That’s not too important to the discussion, though.

I was mentioning Ninja as one basic item but there are plenty more…like the idea that all Asian kids know martial arts. That’s pretty 80s and is probably offensive to a lot of Asian kids that don’t know martial arts. However, since we aren’t at odds with their culture right now, it’s not a big deal and something that just get rolled eyes instead of outright calls of racism. I bet it would be a completely different story if we were in a conflict with Japan or China now, though.

I think ultimately it’s just really important to actually know people from the culture you’re about to explore or at least someone that knows the history so you don’t have the appearance of being insensitive. These days you run the risk of being vilified by some people who are eager to point out Western racism and injustice just to exorcise their own white guilt.

And by “know somebody” I mean have somebody to check your work with…not a “it’s okay I have black friends” situation.

Nope, no ninjas. Apparently, ninja was originally a verb of sorts; samurai would go on stealth operations, which was referred to as ninjaing, more or less. But a particular group who dressed in black and had special weapons and were specially trained assassins — never happened. Really; I looked in books and books on the subject.

The ninjas black costume comes from the fact that they were in plays; they wore black for the same reason puppeteers wear black; it was a costume.

Someone made up a lot of shit on Wikipedia, then.

Yeah, I don’t really doubt that. The internet was pretty unhelpful.

I looked at that Turnbull book they use as a source for a bunch of it. If I’m remembering it right, it was pretty amusing in the way it sort of tiptoed around the fact that there maybe probably weren’t really ninjas.

The last paragraph of the Wikipedia introduction sort of walks it back a bit, doesn’t it?

This was all a while ago that I was researching this, unfortunately, so I can’t cite chapter and verse now, alas. It was a pretty frustrating/weird process. I started out trying to nail down when/where exactly the idea of ninjas came from, and couldn’t do it and couldn’t do it…and slowly it became clear that the reason I couldn’t do it was that it was a trope.

It seems like there were some real-life antecedents for the trope, but it’s a lot more tenuous than the link between, say, actual cowboys and film cowboys. More like the the link between actual law-enforcement personnel and superheroes, I think.

Noah’s a comment ninja.

The Turnbull book is by Osprey press; if it’s the same series I’m thinking of, it’s kind of pop military history. Not bad per se, but more directed to those doing reading for fun or in school, and liable to address topics with a light hand.

I could probably get our East Asian bibliographer to suggest some better sources, if anyone is really interested.

I will spare everyone my Obligatory Cranky Academic Librarian Rant Featuring Eyebrows of Doom and a Frowny Face about the quality of Wikipedia.

Pop military history is right. Pretty good, but not interested in puncturing anyone’s dreams of ninja.

I know I’m coming late to this discussion, but I wanted to comment. Certainly the depiction of Iraqi kids playing in the rubble of Baghdad at the end of the story, in the shadow of this mourned Dream-Baghdad, is a cliche that Edward Said would have hated. I don’t remember Gaiman’s text exactly, though, but I think one way Gaiman could have massaged the message of the story is by how he framed the carnage of Baghdad at the end. In essence, to de-Orientalize this Orientalist story a bit, Gaiman would have to explicitly point out the Iraq war and Western complicity in the ruinous state of Baghdad, to overcome the Western tendency to automatically blame the Arabs for everything that’s wrong with their present-day country and why it doesn’t jive with the Western fantasy vision.

That said, though, I don’t think the idea of the Iraqi kid fantasizing about the Arabian Nights is necessarily unrealistic. I mean, the 1001 Nights *is* an Arab story. Costume period dramas with knights riding through the desert on horseback *are* produced on Arab television. These things don’t have quite the same extra flavor of exoticism that the West overlays on them, it’s not all “savagery” and “fallen-from-grace lost civilizations” and all those cliches of course, but it is possible to see dudes in turbans fighting eachother with swords in media produced in the Middle East, not merely in Frank Miller comics.

Still… …. … yeah, it *is* unlikely that some random poor Iraqi kid is dreaming about the Arabian Nights, since the general assumption (reality?) is that poor people don’t spend as much time fantasizing about total fantasies and fairy tales as bourgeois/rich people. But is that to say that *no* barely-eking-out-an-existence people in the Third World are into that stuff? That there’s no poor kids who like science fiction and fantasy and whatnot? That seems reductionisitic in its own way. People do self-exoticize their own cultural past too, not just the pasts of other cultures, after all; I mean, look at Renaissance Faires. Of course, Renaissance Faires are a Western invention. As an American colonial in an invaded land, I can’t imagine what it’s like to have a ‘history’ literally at my feet the way people do in other countries, and perhaps it’s this distance from history that makes Americans like this sort of stuff so much… although this sort of exoticized-history fantasy-love also happens in European countries and to an extent in China and Japan and really anywhere where people have a certain standard of living and the leisure time to fantasize about these things. My personal feelings are that self-exoticization and the whole idea of ‘exoticism’ is a luxury for bourgeois/rich people, but rather than criticize the idea of exoticism itself, I’d rather dream about a world where everyone lived in such comfort that they were able to indulge in such fantasies: Renaissance Faires for everyone! Perhaps having such fantasies continually projected onto you from without, though, makes one less interested in them.

Yeah; that all makes sense.

I think it’s the way that the story blames the king for not clinging to the fantasy and thereby leaving the Middle East in misery that rankles, too. Not that Iraqis aren’t responsible for their own mess in a lot of ways…but suggesting that they’d all be better off if an Orientalist (and in this case, Western-created) vision had been more thoroughly foisted on them seems really problematic.

Hi Noah! I started writing another comment before I saw your post…! “Ramadan” is an Orientalist story in a liberal self-aware way, but no more so than any Western story about genies and flying carpets. It’s certainly not as egregious as “Habibi”, with its sexual stereotypes and pretensions of teaching the reader about Islam and Arabic culture. But my point is, it’s not particularly unrealistic to depict an Iraqi kid thinking about the 1001 Nights; remember, this is a *kid*, after all, not some adult intellectual, and secondly, the 1001 Nights are originally Arabic, regardless of whatever stereotypes Western culture has overlaid upon them. It’s like he’s fantasizing about Disney’s “Aladdin” (although given the world-spanning grip of Western pop culture, who knows which is more likely… :/ )

It’s been ages since I read it, but I didn’t feel that the story blamed the king for his decision. My impression was more like he managed to save the fantasy, even though the reality was doomed to collapse with time.

I did reread it for the post; I definitely felt like he was being chastised for his hubris…but maybe if you reread it you can tell me what you think!