In terms of mainstream culture, Chester Brown’s Paying for It—a diaristic account of his experiences of paying for sex between 1999-2002—has been the most discussed comic of the year. And apart from Robert Crumb’s Genesis, probably the most widely exposed of the past half-decade or so. This is not surprising, since it addresses polemically a difficult and largely unacknowledged but perennially challenging issue: prostitution and the underlying question of how sexuality straddles identity and commodity.

In an pre-publication comment on this site, Noah took issue with an early review by Tom Spurgeon, which he saw as unwilling to engage with the socio-political issues addressed in the book—something he took as emblematic of how comics critics tend to prioritize form over content, simply put. Never mind that his examples of such priorities in comics criticism were highly tendentious, he has a point that there is a holdover from traditional comics appreciation that privileges form, even if contemporary criticism increasingly transcends it.

In an pre-publication comment on this site, Noah took issue with an early review by Tom Spurgeon, which he saw as unwilling to engage with the socio-political issues addressed in the book—something he took as emblematic of how comics critics tend to prioritize form over content, simply put. Never mind that his examples of such priorities in comics criticism were highly tendentious, he has a point that there is a holdover from traditional comics appreciation that privileges form, even if contemporary criticism increasingly transcends it.

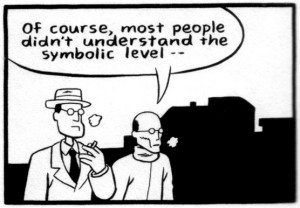

As it has turned out, however, the reception of Paying for It has generally engaged Brown’s polemics head-on, to the extent—ironically—that the form in which they are presented has been largely ignored. Noah himself has done better than most on this issue. In his review, for example, he makes the important observation that Brown’s dispassionate presentation and robotic self-portrayal can be seen to reflect and inform his ideology and political message.

Beyond that, however, he reveals a lack of sensitivity to Brown’s artistic achievement. In a subsequent comment, he writes about the book: “formally it doesn’t really do very much…but I guess that’s autobio comics for you….”

Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form.

Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form.

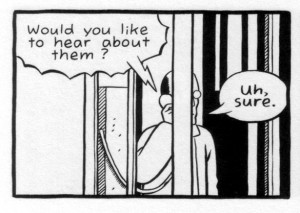

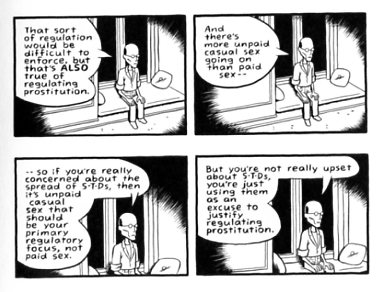

As a polemic, the book is forceful and compelling, but it founds its basically well-reasoned political stance on an idiosyncratic, ineptly argued rationale. Brown’s position that prostitution should be decriminalized but not regulated, though founded in libertarian ideology, is pragmatically rational. Much of the rest of his discourse, however, is less so: not only does the basic premise, that romantically founded relationships are (probably) inherently wrong, seem more of a personal exorcism than a universal truth, but more specific arguments also grate against lived experience. Readers with any knowledge of substance abuse, for example, may find themselves mystified by Brown’s assertion that dependency boils down to rational choice and has no physical symptoms (appendix 17).

Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).

Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).

Dubious in relation to any human relation, the libertarian notion of humans as autonomous engines of dispassionate choice and our bodies as property rather than incarnation (appendix 4) is downright absurd when applied to something as emotionally fraught and psychologically complex as sexuality and its commodification in society. Brown seems to believe that hard currency is some kind of elixir for human relations. Although he clearly does not even contemplate fatherhood, he for instance expects us to accept that his utopia of commodified sex and contractual child-rearing (appendices 3, 18) would somehow make for a healthier, more nurturing environment for children to grow up in.

Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement.

Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement.

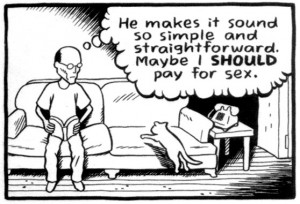

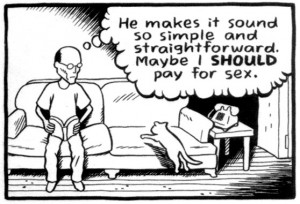

I would thus agree with Spurgeon’s argument that Paying for It, the comics memoir, is richer and more satisfying than the preachy appendix. The concomitant conclusion, that Brown would have done well to leave out the latter, however, is less convincing. The narrative gains in power as a tangled, resonant substructure for the polemic, and the political argument is both bolstered and countered by the lived experience girding it. Where in the appendix Brown is happy to make dogmatic and at times fairly extreme statements, in the comics he allows space for counterarguments, voiced by his friends as well as a couple of prostitutes, one of which—as Noah and others have pointed out—challenges outright his philosophy as lazy, arguing that the kind of hard work that goes into a romantic relationship is required for anything of value in this world.

And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.

And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.

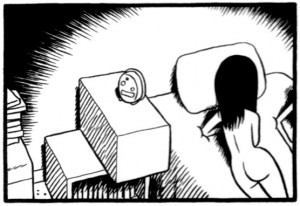

And his strategy of obscuring the faces and changing any distinctive features or characteristics of the prostitutes, avowedly done in order to protect their privacy, not only makes manifest on the page the objectification inherent in the book’s subject and ideology, but reveals Brown’s commitment to authenticity. Instead of turning them unrecognizable by changing their appearance, he makes them anonymous. In contrast to colleagues such as Steve Ditko and Dave Sim (though less so with him than one might think), Brown’s instincts as an artist are simply too sound for him to let his work conform narrowly to ideology, no matter how strongly he feels about it.

One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book, Louis Riel (2003), will remember its conflicted protagonist, believing himself to be acting according to divine ordinance and finding that other designs may be confounding his freedom of action. The possibility of free agency is a central concern.

One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book, Louis Riel (2003), will remember its conflicted protagonist, believing himself to be acting according to divine ordinance and finding that other designs may be confounding his freedom of action. The possibility of free agency is a central concern.

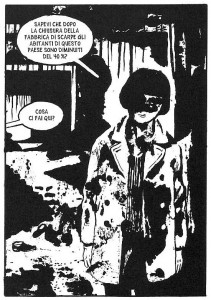

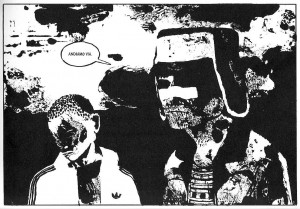

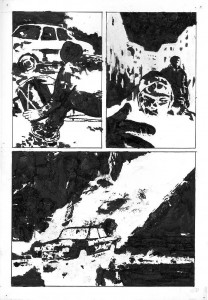

Though it is less overtly spiritually charged, this problem remains somewhere at the core of Paying for It, which sees Brown more pointedly championing his choices in the face of social norms. And although he no longer confesses as a Christian, and has orchestrated his most spartan mise-en-scène yet—a far cry from the vintage texturing of Riel—his images are still imbued with a compelling sense of meaning. One gets the sense that the detachment with which he describes his experience is the same as the one with which he examined the life of Riel.

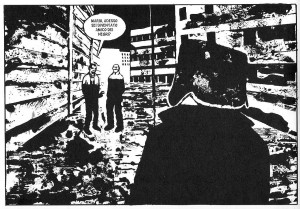

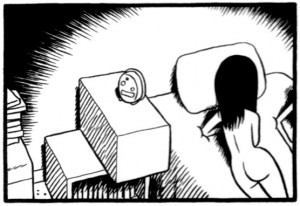

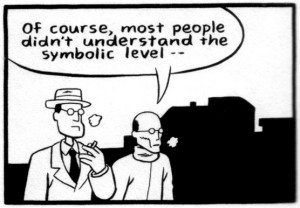

As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

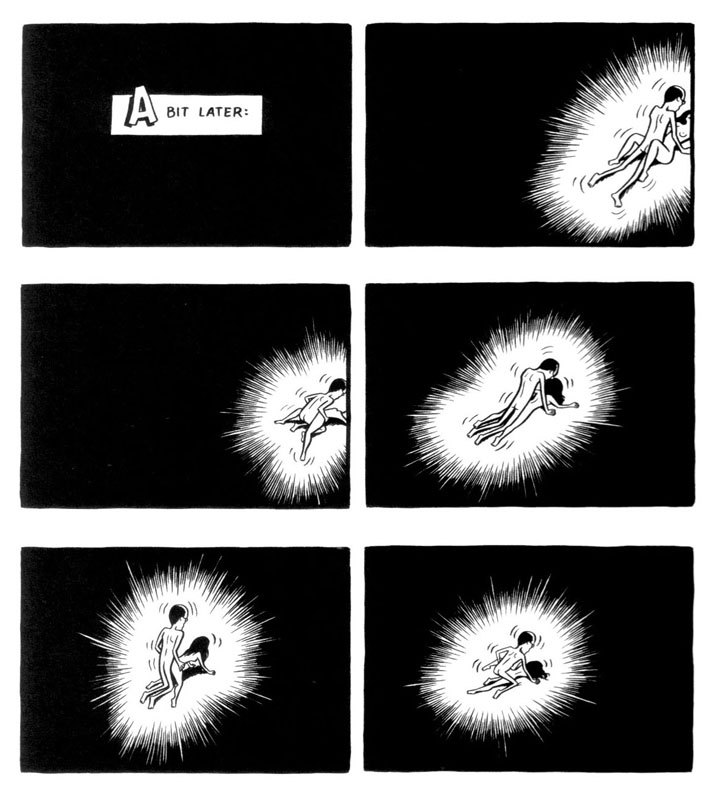

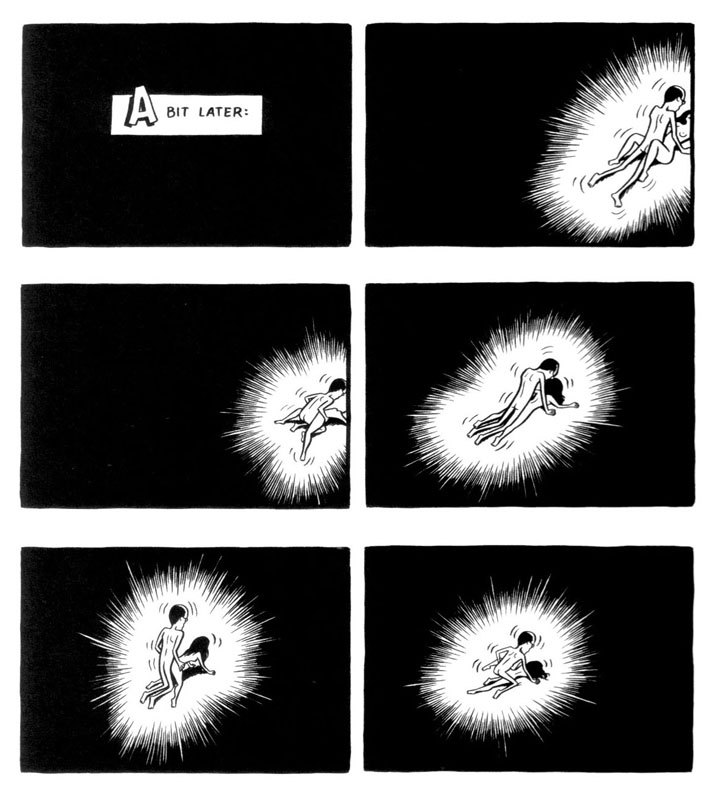

Sex scenes are privileged by even greater distance. They are uniformly denoted by a throbbing glow in the dark, blocking out the surroundings (this is worked to hilarious effect in chapter 2—the sequence where Chester keeps stopping, with the banal details of the surrounding room appearing each time). A necessary way of avoiding the interference that overly graphic renditions would create, this approach lends universalism to these scenes, threading them through the narrative as its central, ‘sacred’ constituent.

Brown’s cartooning has struck me as invoking this kind of higher order since at least, and unsurprisingly, his 1990s Gospel adaptations, which routinely employed a similarly elevated perspective, pared-down panel compositions, and suggestive framing to great effect. The explosion of the grid in I Never Liked You (collected 1994) and the claustrophobic, petri-dish effect of the gridding in Underwater (1994-97), each in their way seemed to solicit scrutiny from above. In Paying for It, Brown works to great effect the inevitable, often ominous, signification of gestures—frequently singled out in individual panels; the incursion of random passersby in streets backed by theatrically silhouetted buildings; and the suspension of time and motion as Chester and his friends Seth and Joe Matt stride down the street, their talk at an end.

The point is that Brown, contrary to Noah’s dismissal, always achieves a lot with his images and panel-to-panel storytelling. His power to imbue any scene with an ineffable sense of meaning is one of his great gifts as a cartoonist, a gift few critics have attempted to critique or explicate, and which Spurgeon addressed sensitively in his review.

Paying for It is a brave book, groundbreaking in its premise alone, but beyond its polemic it is an unflinching self-portrait, synthesizing its author’s ideology, sexuality, pathology, and spirituality on the page.

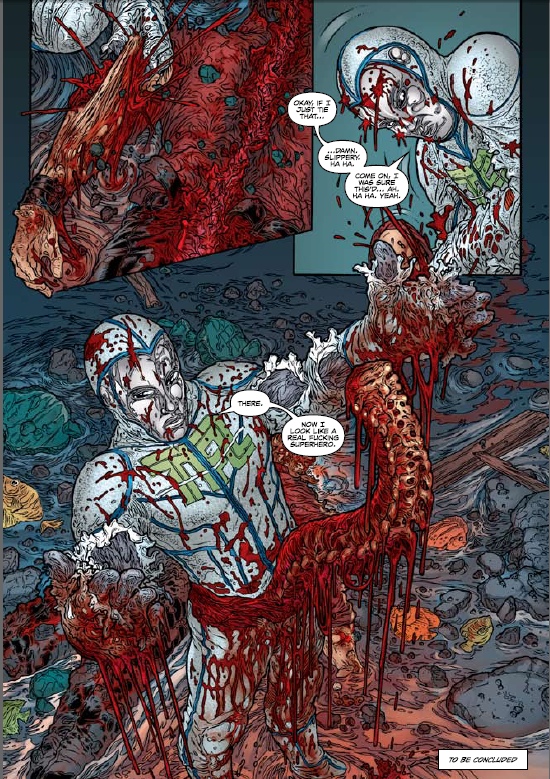

Carver’s transformation leaves him a hideous mess. His skin is falling off to be replaced by some hard purple material and he’s become, “castrated.” Another hero named Ben/Redglare tries to comfort him but Carver starts to freak out and break everything before realizing he can do so because he has powers at which point he’s…happy. Either Carver was so desperate to achieve his ideal of a hero he was willing to sacrifice a huge aspect of it, or something else is up.

Carver’s transformation leaves him a hideous mess. His skin is falling off to be replaced by some hard purple material and he’s become, “castrated.” Another hero named Ben/Redglare tries to comfort him but Carver starts to freak out and break everything before realizing he can do so because he has powers at which point he’s…happy. Either Carver was so desperate to achieve his ideal of a hero he was willing to sacrifice a huge aspect of it, or something else is up.

In an pre-publication

In an pre-publication  Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form.

Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form. Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).

Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).  Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement.

Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement. And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.

And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.  One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book,

One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book,  As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

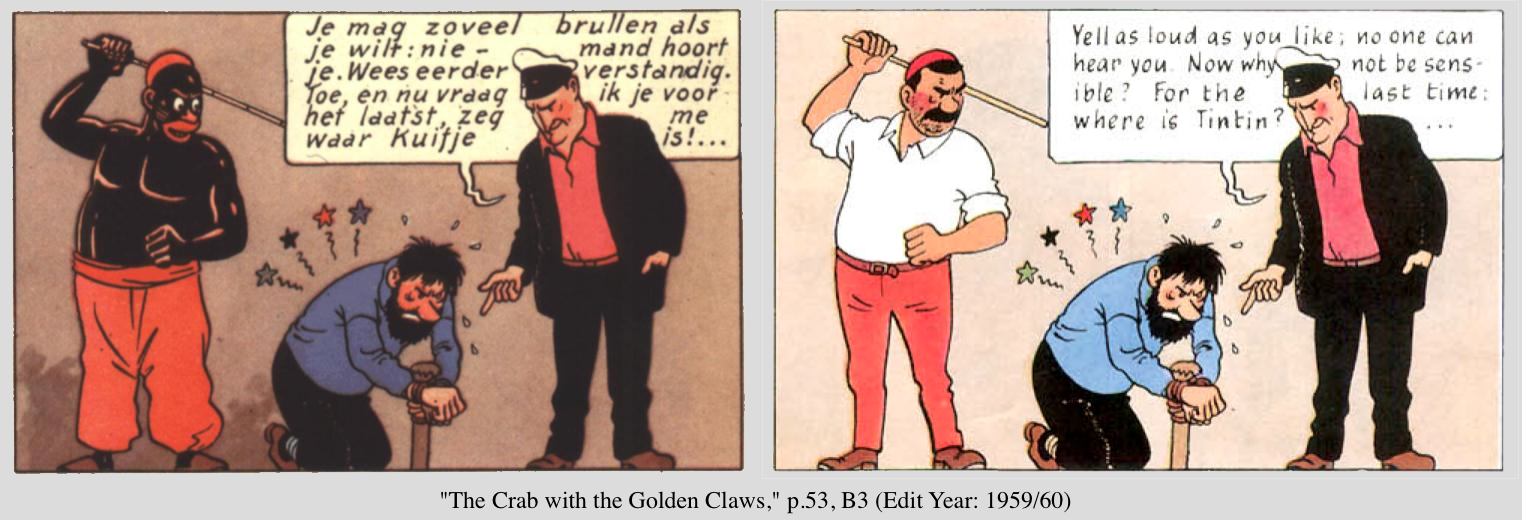

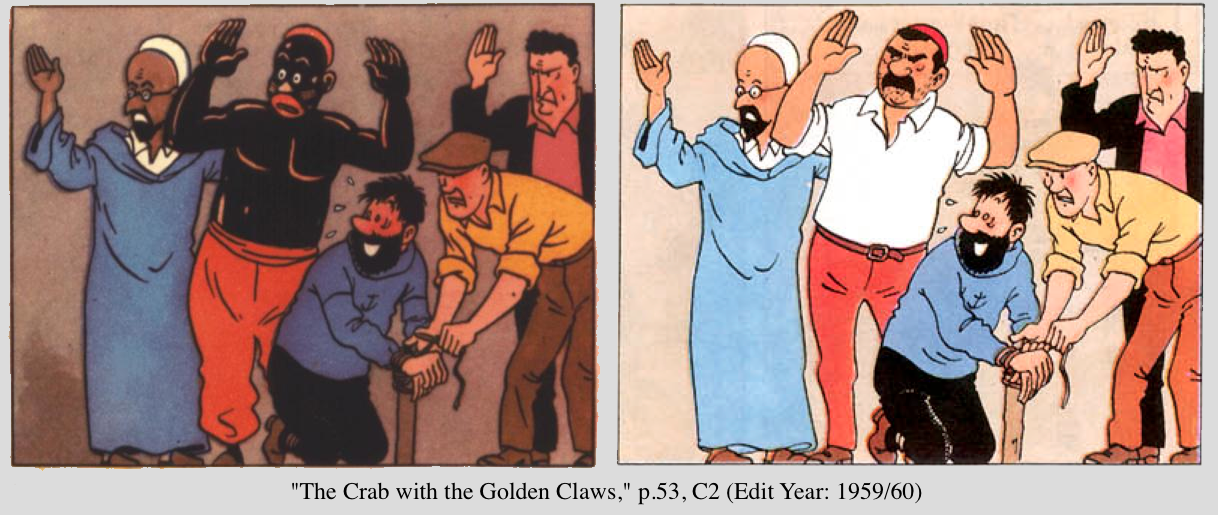

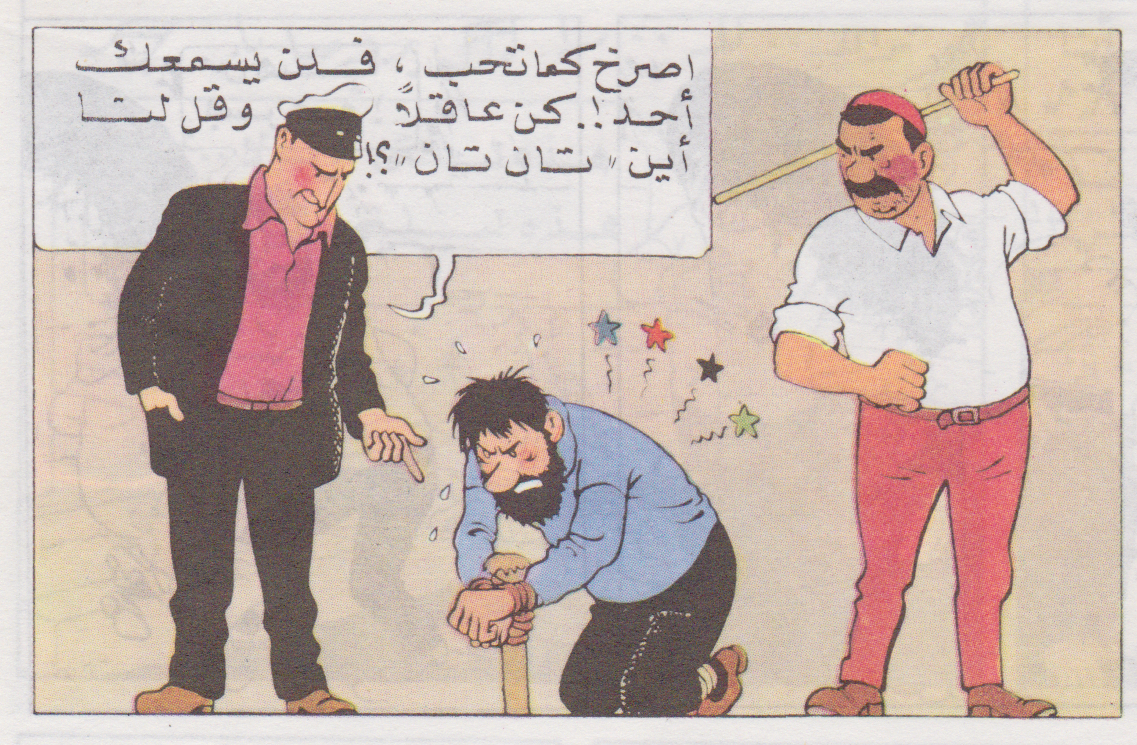

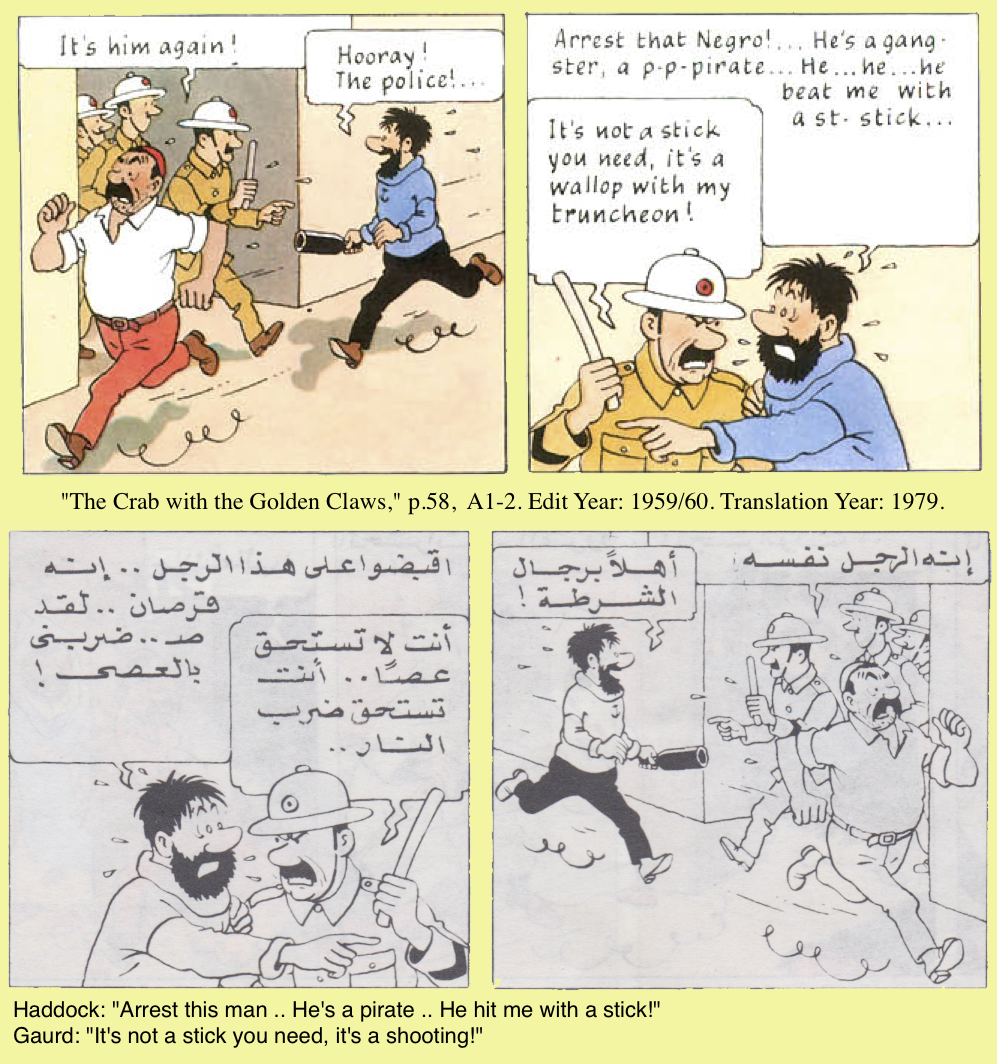

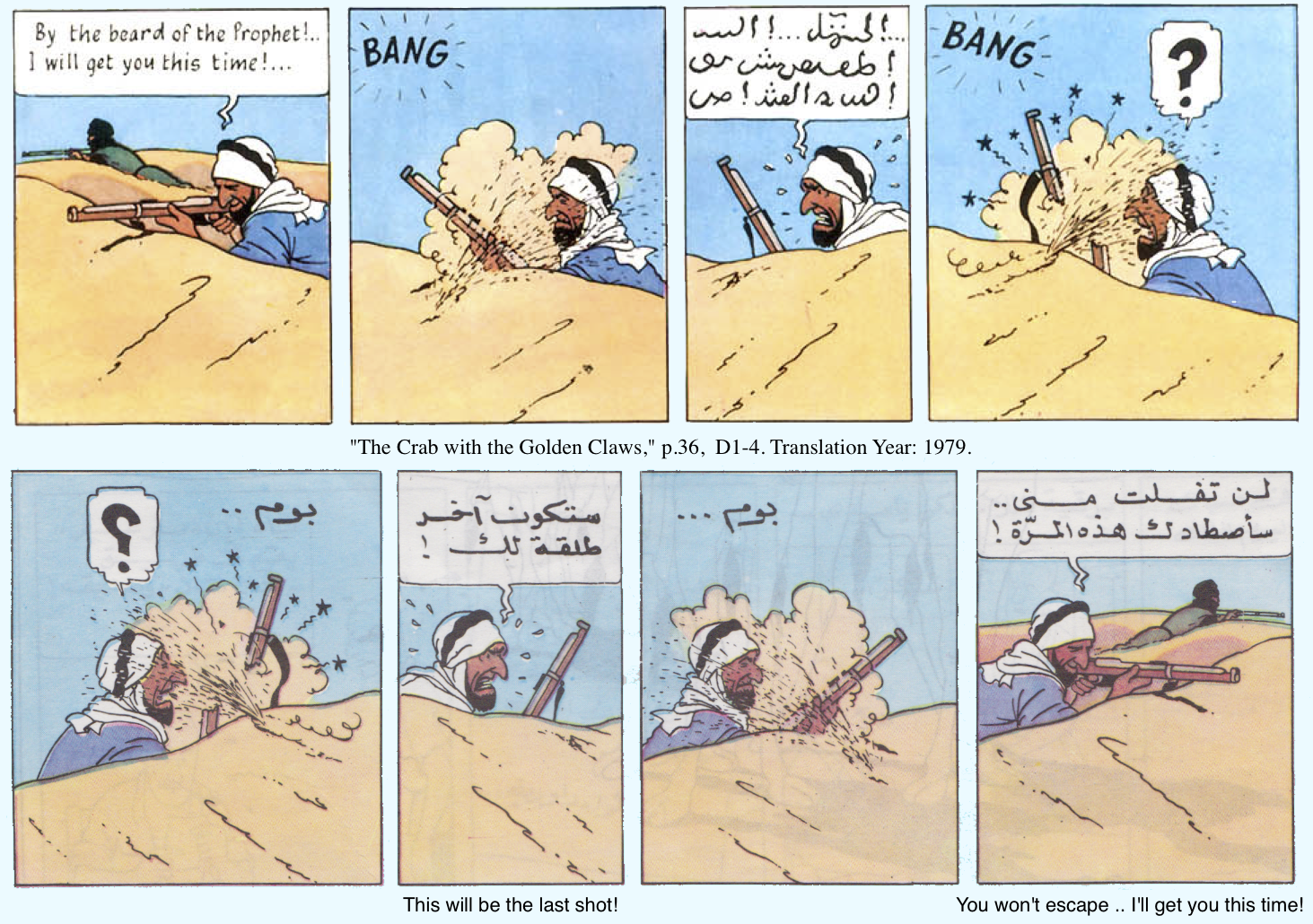

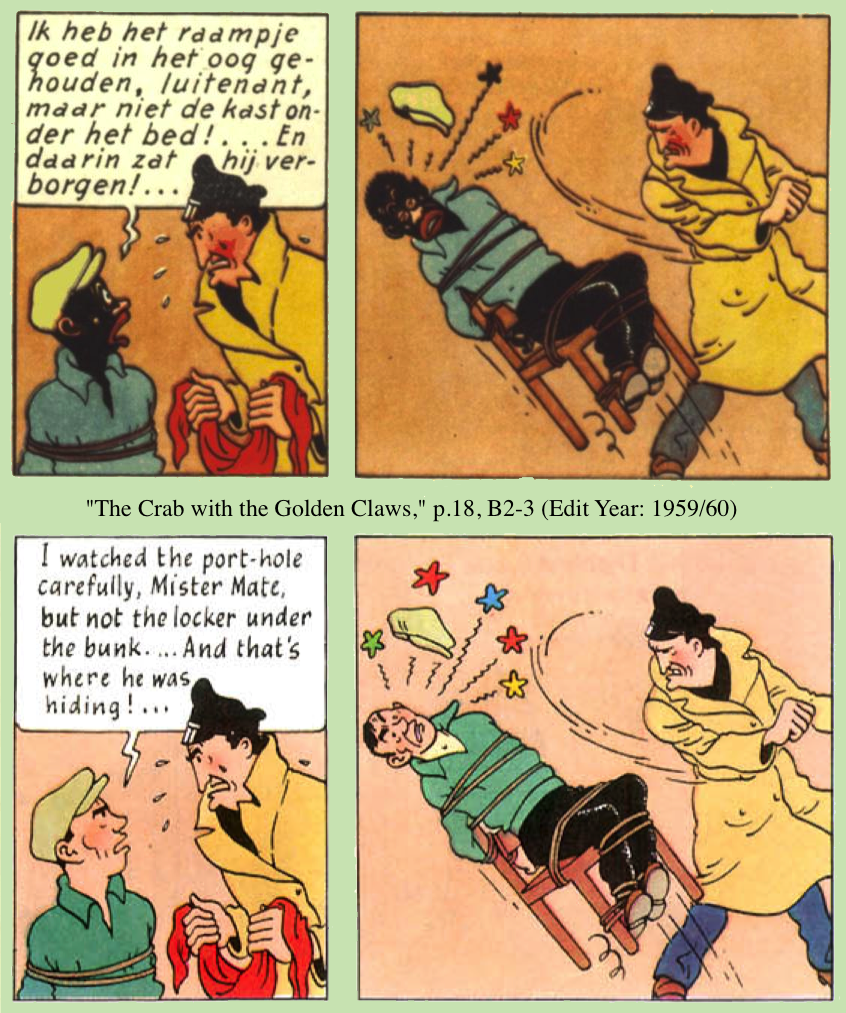

Deckhand “Jumbo” becomes markedly whiter.

Deckhand “Jumbo” becomes markedly whiter.