Click on images to enlarge

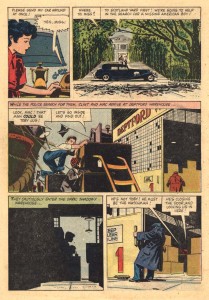

IDW’s Genius, Isolated is a gorgeous, impressively scaled hardcover with many crisp reproductions from original comic pages. The first of a series of three volumes that are being hailed as the definitive statement on the art of Alexander Toth, it continues the high production standards set by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell’s previous excellent, essential collections of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates and of Noel Sickles’ work. But I must begin my critique to say that the elegant, conservative design that works beautifully for an artist like Caniff feels a bit staid when applied to the daring, moody angles and croppings of Toth—I hope that his great work of the 1960s and 70s, to be covered in the second volume, will be presented with a somewhat more elliptical, dramatic design, as befits that period of the artist’s work.

I have IDW’s Sickles book and admire it greatly. I just read several of Mullaney and Canwell’s Caniff volumes and was hugely impressed, by the quality and scale of Caniff’s achievement and by the the editors’ presentation of his life and work. In one of these incredible collections, though, a passage disturbs me—in his introduction to Terry Vol. 3, Pete Hamill writes of the strip’s millions of readers: “…almost certainly they were not reading it for the increasingly wonderful drawings. They were reading it because of the characters and what they were doing. That is, for the stories.”

This is a basic misapprehension of the comics form. In comics, the reader “reads” the images as much as the text. The art joins with the text to a common purpose, the story—which might be furthered, for example, by a drawn expression that shows an intent that is hidden by what the character is saying in a dialogue balloon. Caniff’s art is not redundant, it communicates nuances that are not expressed in his text, or it supplements the information provided by the text. Cartoonists make decisions in their orchestration of word and image in the form of a page which greatly inform and affect the reader’s perception of the narrative. Hamill discounts the contribution of Caniff’s exhaustively researched imagery to the success of the work as a whole; the precise way, for instance, that he is able to bring the vital, proactive female characters that propel his storylines to life in his drawings. And unfortunately, a similar misconception seems to be held by the editors in their book on Alex Toth.

Rather than an art book, Genius, Isolated is a biography accompanied by a selection of photographs of the artist, along with many of his original pages and happily, a selection of complete graphic stories. Despite the pleasures of Toth’s art, though, a dispirited tone of unresolved conflict and failure to communicate permeates the book. There is precious little upside or sense of aspiration or inspiration, of a dedicated artist breaking boundaries. The greater part of the text tends toward the exposure of the faultlines in Toth’s professional and personal life. We are informed in depth about Toth’s life-long depression, his inability to compromise, his lack of diplomacy and outright rudeness to all and sundry. The artist’s family and friends provide a lot of personal data and observations, all valid grist for the mill in a biography of a man who was a seriously troubled and problematic individual, I’m sure. Still, long-speculated-about issues regarding his parents are laid out but remain unexplained, the names of his first two wives are not established, we read of the pathetic ending of his third marriage, the fight he had with DC editor Julius Schwartz is forensically examined…some of this is either too little information or too much and sometimes, it feels like no one’s business but the Toths.

Genius, Isolated disempowers its subject by focusing on his personal life while failing to articulate what it is about his storytelling that made it special. In this volume, the text does not make a case for genius. The art does, with some reservations. The artist did much of his formative work for DC Comics, but they seem to be saving their early Toth holdings for a collection of their own, since there is only one DC story (a good choice, though: “Battle Flag of the Foreign Legion”). The group of Standard stories reproduced from the original art herein have been reclaimed from Pure Imagination’s reservoir of bleached and restored public domain reprints, but there is not such a clear demonstration of Toth’s rapid growth within the space of a few years in the early 1950s, or an analysis of his form and practice as Greg Theakston attempted in his two-volume Toth: Edge of Genius. Here, the work must largely stand on its own virtues, while the text portrays a man with deep psychological problems, who happened to also be blessed with superior drawing and design capabilities and simultaneously cursed with OCD.

Some new insights are offered by several of Toth’s contemporaries such as Irwin Hasen, John Romita Sr., Joe Kubert, Mike Esposito and Jack Katz and the artist’s private correspondence with friends like Jerry De Fucchio is quoted, but a significant portion of the information related to Toth’s artistic sensibility and process is liberally culled from interviews with Toth’s contemporaries that were conducted by the dedicated comics historian Jim Amash for the special Toth issues of Twomorrow’s Comic Book Artist (#11) and Alter Ego (#63). Then, the selected quotes often seem intended to support explications of one or another of the artist’s perceived negative qualities. Toth speaks for himself occasionally (and not in his own hand, his writings have been typeset), but often his detractors are allowed to qualify the work. Kubert takes the opportunity to defend his allegation that Toth hacked out the “Danny Dreams” story in Tor #3 by drawing it at print size, even though it is plain from virtually the rest of the book that it wasn’t ever in Toth’s nature to take the easy way out. Toth’s efforts to improve the material he worked with are presented as proof that he was “difficult” since he wasn’t able to keep to his assigned place as an illustrator. Yet, the book seeks to define Toth as an illustrator and in this buttresses past misconceptions about his work, and by extension that of all comic artists who work with writers.

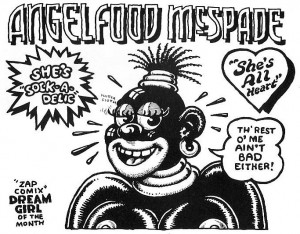

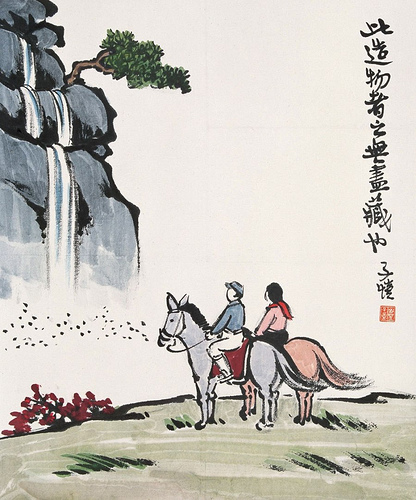

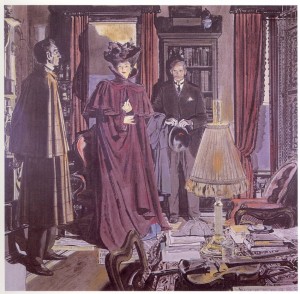

The authors’ choices of which of Toth’s influences to highlight are unexpected and seem intended to press a view of him as more of the lineage of illustration than of comics. The “influences” section is comprised of images and capsule biographies of several obscure illustrators. While I don’t begrudge them their renewed visibility, I wish there were images of the works of Robert Fawcett and Albert Dorne, illustrators whose work strongly affected Toth, in a book that means to be definitive.

- An elegant illustration by Robert Fawcett

Toth is a cartoonist, but his comic artist heroes are placed outside of the “influences” section. A few Scorchy Smith dailies are shown, despite that the impact of Noel Sickles’ later graphic work on Toth’s drawing techniques is as pronounced, or more so. The authors do show a clear correspondence of his neophyte efforts to Frank Robbins’ early work, yet Roy Crane, arguably Toth’s most overpowering muse, rates only a single repro of a relatively weak Wash Tubbs daily strip.

- Buz Sawyer: a more substantial example of Roy Crane’s talents.

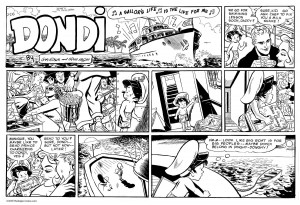

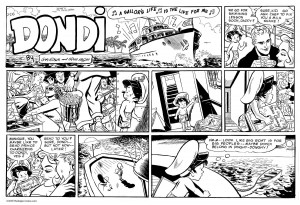

Irwin Hasen was a mentor and friend to Toth and by the artist’s own account, another prime influence on his work. Hasen gave the authors many quotes, but his artwork is not deemed worthy of a reproduction. In an interview with the author/editor team on TCJ.com, Dan Nadel hones in on this omission and asks, “What did Toth see in (Hasen), as opposed to the flashier, more obviously influential Meskin?” Mullaney reponds, “It could very well be that Alex admired Irwin because he was a working professional that Alex wanted to be. Irwin was certainly among the better artists at DC at the time. It’s a question only Alex could answer.” If one actually looks at Hasen’s work, though, a connection can be seen—-his storytelling, his internal “camera” and page compositions are clear and succinct, his brushwork is fluid and expressive.

- Mad fresh: Dondi daily strip by Irwin Hasen

- Breezy brushwork by Hasen on a Sunday.

From childhood, I always could see that Hasen drew appealing comics pages. I trust Toth when he said he learned something of value from his friend’s work—I’d guess that the calculated and deliberate Toth admired the light freshness of Hasen’s handling.

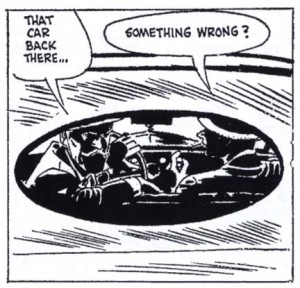

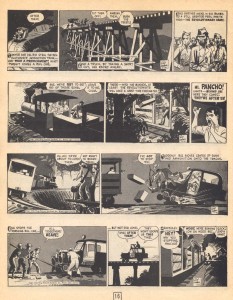

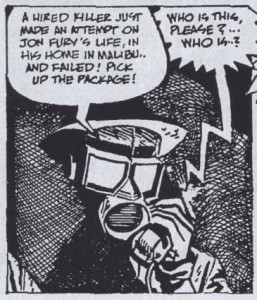

A case is presented that Toth is not much of a writer himself. This is firstly evidenced by an early, incomplete and unseen story, interesting mainly for the rare look at his pencils. Obviously Toth wasn’t happy with it, since he didn’t finish it. He did a later version, “Tibor Miko” from Creepy #77, that wasn’t much better. Then, there is the interminable exposition of his self-written Jon Fury strips for the Army, included here in their entirety or nearly so, although some strips are presented in a badly retouched form (I feel sorry for the production artist who was charged with this task).

- Retouched panel from Jon Fury

In Fury Toth tried to emulate Caniff’s writing but falls flat, most embarrassingly so when he phonetically renders the dialogue of Fury’s Mexican hoax wife in the inexplicably typewritten third storyline. The Jon Fury strips are nearly anomalous in Toth’s corpus in that they are so annoyingly hard to read. Granted, he had a difficult time initiating a script, but usually once he had a script, he was a master at making it work.

In his preface, Mullaney writes that Toth “would accept drawing assignments, ignore the supplied scripts, and unilaterally rewrite at his own discretion.” But—-Toth didn’t ignore scripts and his amendments were never unilateral. Instead, he served the story, he made every effort to find the story’s heart. Any alterations he did on scripts that he accepted were based on his instincts of what the story needed. He did the lettering whenever possible, not only for the aesthetic of his unique hand making the finished page, but for the control lettering gave him to (usually) subtly amend the script and streamline the narrative. What illustrator has ever taken it upon themselves to alter the text of a story? It isn’t done. But Toth continually proved that he deserved such freedom in interpretation and in his efforts, he certainly shortchanged no one. Ironically, even his least sympathetic editors and writers have been the beneficiaries of Toth’s unpaid improvements—his works are often the jewels of their careers.

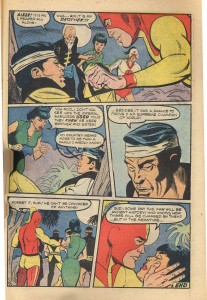

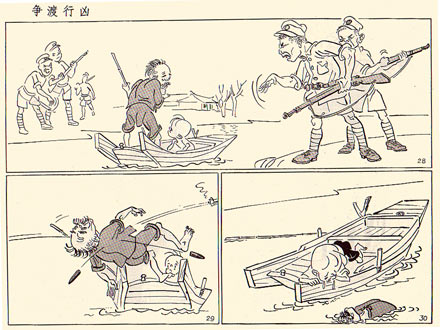

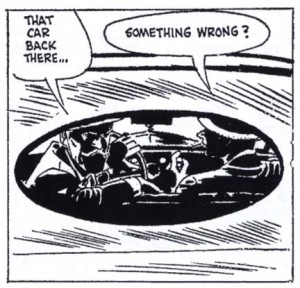

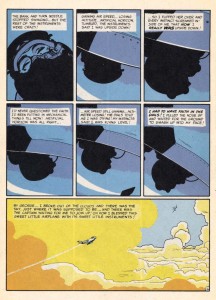

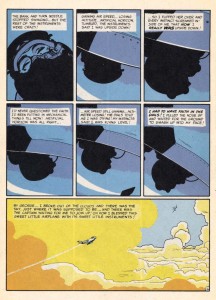

The overwhelming majority of the scripts Toth drew would hold no interest today if he had not drawn them. An exception is the transcendent yet faithful enhancement of Harvey Kurtzman’s “Thunderjet” that is reprinted here. However, Toth was unable to adhere to the writer/editor’s exactingly articulated layouts for their most brilliant collaboration, “F-86 Sabre Jet” from Frontline Combat #12.

- F-86 Sabre Jet: one of the best pieces either man ever did.

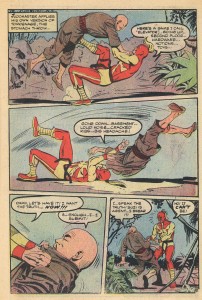

As can be seen from the page above, Toth did not alter Kurtzman’s structure. His offense was that he chose to use oblique silhouettes in the upper tiers, a relatively small change but one which greatly augments for the reader the sense of disorientation communicated by the text and experienced by the pilot. An angry Kurtzman printed the story, but Toth did no more work for E.C. Joe Kubert’s later outright rejection of Toth’s Enemy Ace story because of the artist’s alterations to the script is atypical—most of Toth’s editors accepted his improvements. However, these anecdotes do “illustrate” precisely why Toth was not an illustrator. He demanded a level of autonomy in interpretation, even if it meant he would get no further work from a company.

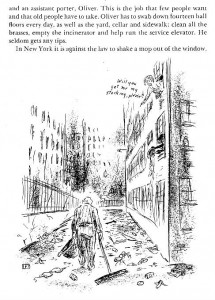

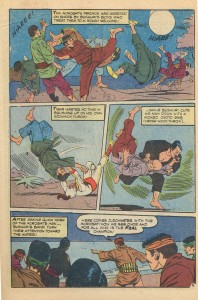

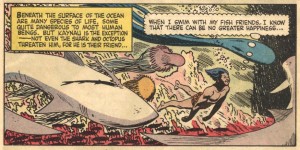

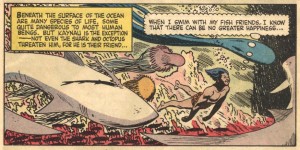

Massive popularity in one’s time is not always a barometer of artistic accomplishment. Toth’s avoidance of the repetition and artistic stasis that drawing series or even full issues of the same character require makes his work hard to find, spread out as it is in anthology titles, and he did not make the regular income that series would have given him. Toth’s son Damon explains, “his integrity was way more important to him than dollars and cents, and he lived by that his whole life.” Yet, the editors insist on supporting the emphasis on character/property that constrains the comics industry and marginalizes peripatetic artists like Toth, by focusing the Dell section on Zorro and including an already much-reprinted story. Although he began with high hopes, the artist disliked the scripts, did not consider Zorro to be his best work and it was the source of the conflicts that ended his Dell employment. His fabulous efforts on some of his other rare book-length Dell comics such as Clint and Mac, Paul Revere’s Ride, No Time for Sergeants and The Frogmen are barely mentioned.

- Clint and Mac: a particularly beautiful comic book

- A memorable panel from The Frogmen #5

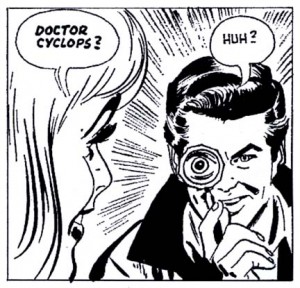

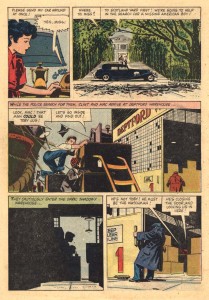

Instead, a twenty page story from Toth’s series of 77 Sunset Strip comics is included, one of the few things in this book that I didn’t already have. It is a bizarre choice, drawn in his more humorous style and it has grown on me, although Toth thought the show and characters were idiotic and this informs his disparately absurd panels, any of which might have been an excellent source for Roy Lichtenstein.

- 77 Sunset Strip: a no-brainer

Maybe Toth was overqualified to work on such disposable children’s entertainment, but he did it because he was driven to use the comics medium as it stood in his time, to experiment with its properties, to our enrichment. He found ways to believe in the scripts enough to transform them, if not into literary masterpieces, certainly into examples of sophisticated comics storytelling. That sophistication most often came from his skills as an interpretive comics storyteller, rather than from an illustrator’s strict adherence and accompaniment to a set-in-stone text. Toth did well-drawn and designed covers and pin-ups up until the time of his death, but what was missed by his disappointed fans for his two final decades was his approach to comics narrative—and that is where his importance lies.

Perhaps some of my problems with Mullaney and Canwell’s approach will be addressed in their future volumes. However, the second book in the series, the one that will represent his greatest comics work, will be titled “Genius, Illustrated,” a title that makes me despair, whatever the editors’ rationale for using it (“it’s about a genius, and it’s illustrated”). I beg them to reconsider that title, even though there would be some effort involved since the book has been solicited. The term “illustration” describes artwork that accompanies a text, but does not impose upon it. An illustrator has a subordinate role to that of the writer and in bibliographic terms is not considered an author, or a co-author along with the writer of a book. Applying this label to the artist’s part of the collaborative process of comics ignores that comics demand many skills not in the job description of an illustrator, such as staging, timing and the emotive acting of “on-model” characters in the sequential representation of shifting vantage points of movement within three-dimensional space.

Toth had a complex skill-set and a consuming dedication to his art that places his work far above that of his contemporaries. If our greatest interpretive cartoonist is saddled with the “illustrator” label, he is denied what he fought for in his many battles with editors, the frustrations of which surely impacted his personal life, conflicts which grew from his efforts to make some of the greatest examples of graphic storytelling to date. If Alex Toth cannot get his due, then all comics artists who do not write their own scripts, but who contribute a great amount of the narrative content of the comics they do within their drawings, are well and truly fucked.