Where oh where do I begin in my attempt to get you to watch Election and Triad Election? I could start in oh so many places. I could start by telling you that Johnnie To is one of the greatest living action film directors, a man who invests his films with his peculiar thematic and aesthetic fixations while only rarely forgetting viewer pleasure. I could talk about the grace and beauty of his frequently long takes. I could talk about his other films, like Breaking News, which begins and ends with nine-minute, single-take action sequences, one a shoot-out, one a car chase filmed from inside the lead vehicle. I could talk about the small repertory company of actors and writers he works with again and again. Or I could just talk about The Wire.

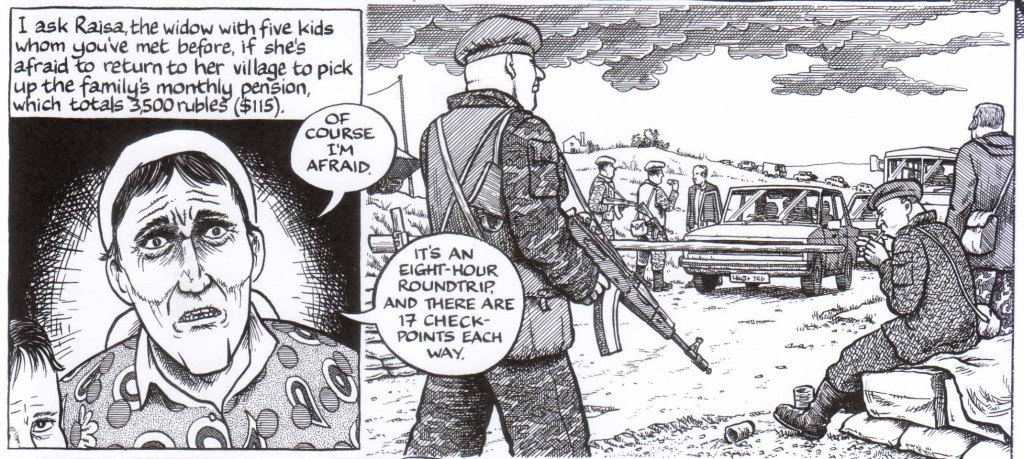

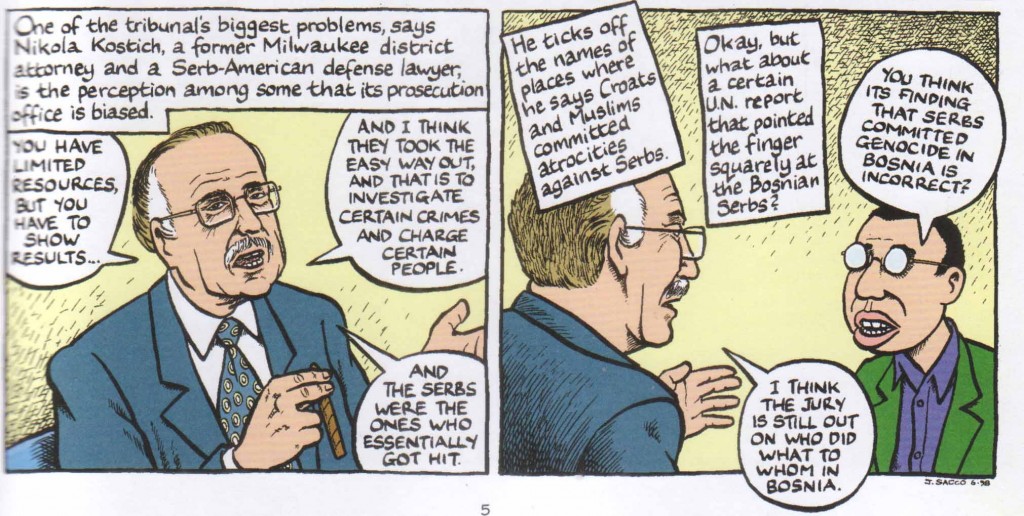

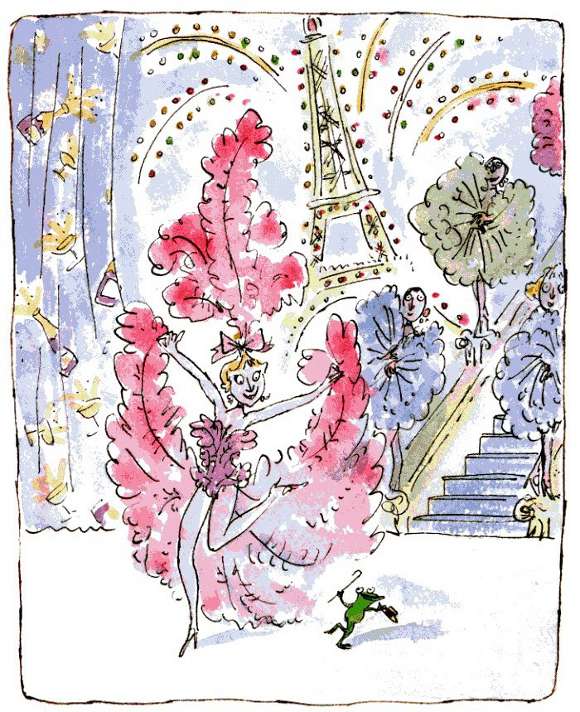

Tony Leung Ka Fai as Big D

It’s a cliché, of course, to recommend something to someone these days by using The Wire. “Oh, it’s like the British The Wire,” or “It’s like The Wire of theater” or “You know this guy wrote the episode where Stringer dies,” and it’s sometimes difficult to divine what we mean when we say this. On some level, we’re just talking about quality, right? We mean that this is an exceptionally well-crafted piece of televisual entertainment. But we also mean that there’s a low level of bullshit and wish fulfillment to its unfolding, a willingness to confound audience expectations and a refusal to pander more than is necessary. By this standard, of course, Season 5 of The Wire isn’t The Wire and neither is anything involving Bubs after Season 4, but we just let that go because, goddamnit, it’s the greatest work of narrative art created by man in the last however many years we want to use to temporally bound our judgment, right?

Okay, so The Wire-as-compliment is a cliché. But clichés become clichés because they have a certain value and in Election/Triad Election’s case, the cliché is particularly apt.

Election and its sequel Triad Election are two halves of a gangster saga set in Hong Kong a couple of years after reunification with mainland China. The premise is not what you’d expect from a Mob Epic. It’s not about family strife, or a war between different mobs—there is one, but if you blink you’ll miss it—or control over territory. No one goes to a therapist or has domestic troubles. No. For if the American Gangster Epic is frequently about the interaction between Capitalism and Family steeped in immigration and the American Dream, the Election films are squarely about Capitalism and Democracy, with Tradition and Individuality thrown in for good measure.

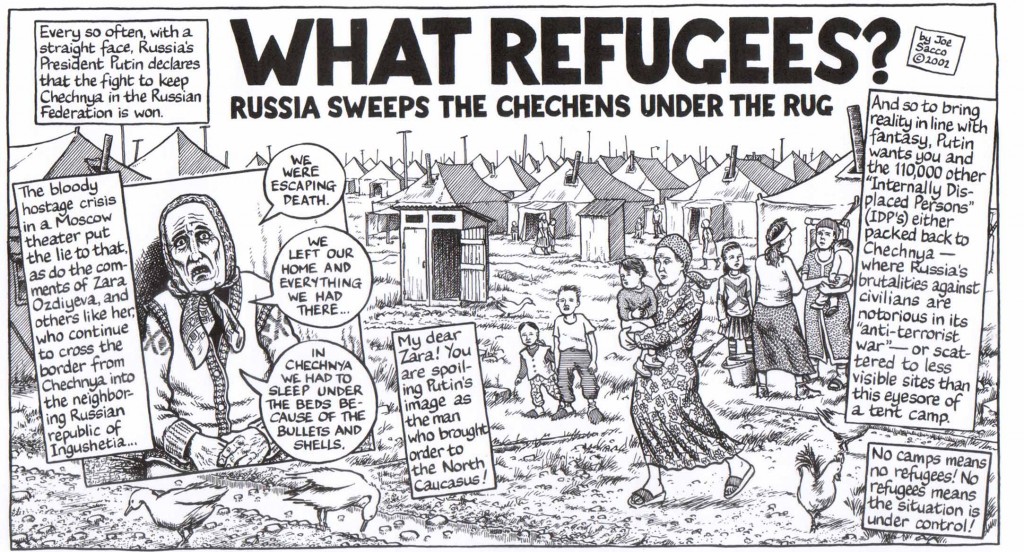

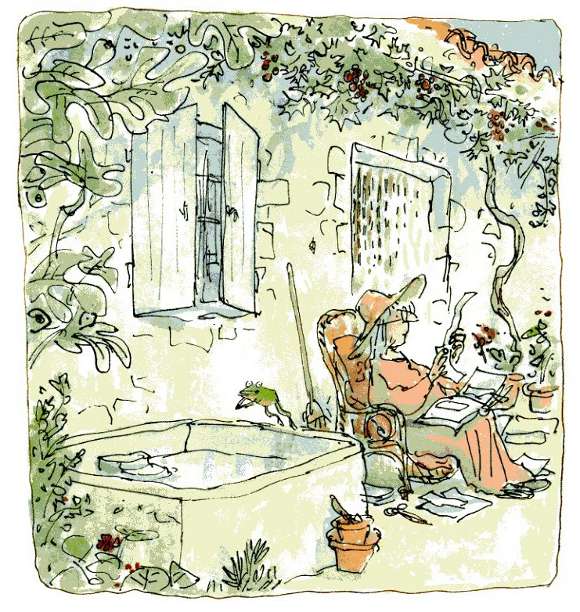

Simon Yam as Lok

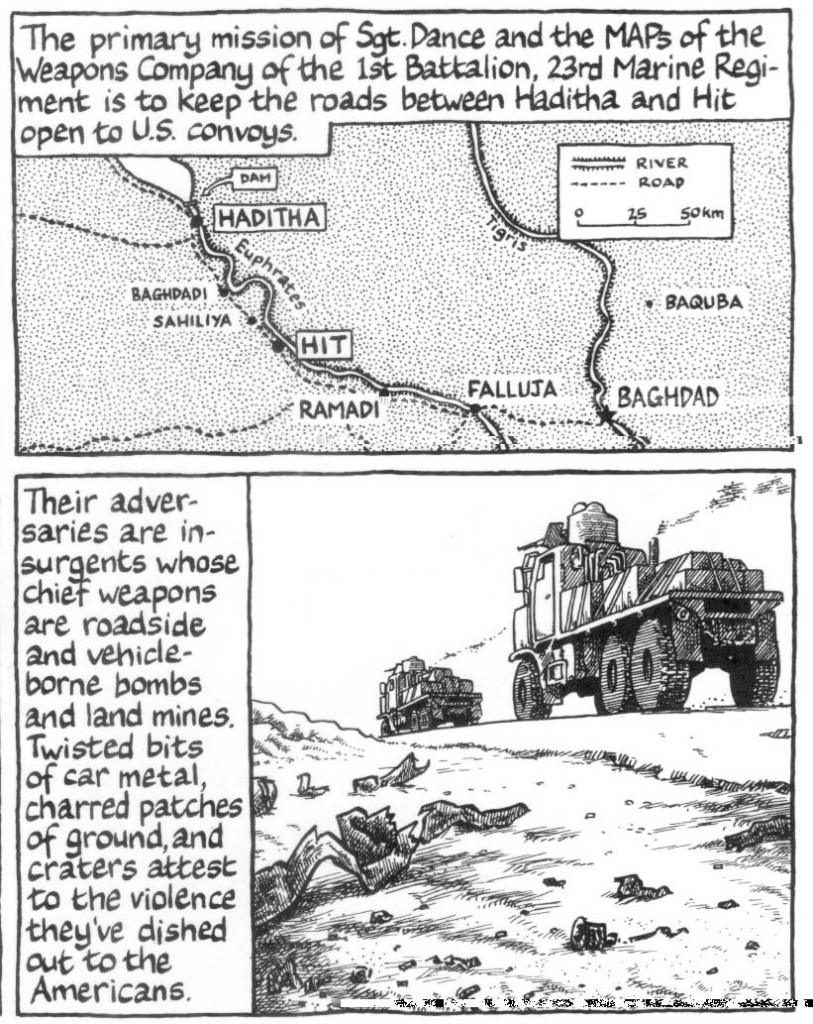

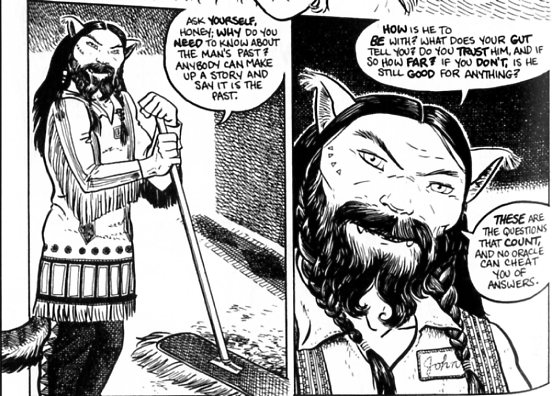

The first film opens on the dawn of an upcoming election, but it’s not for Mayor or Local Dog-Catcher, no, instead it’s for Chairman of one of the dozens of Triads in Hong Kong. A group of old “Uncles” meets to discuss who should be the next Chairman, the flashy and highly profitable Big D (played by Tony Leung Ka Fai) or the sturdy, dependable, quietly ambitious Lok (played by Simon Yam). The early contrast between the two couldn’t be clearer, as Big D is shown buying flashy suits while Lok, a widower, goes to a local butcher for meat to feed his son.

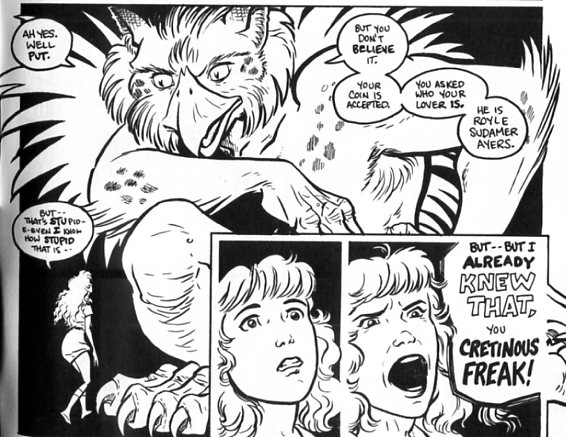

The Uncles quickly settle on Lok, despite Big D’s attempts to bribe his way to the Chairmanship. In his rage, Big D refuses to accept defeat and attempts to steal the Dragon Baton, the symbol of the Chairman’s power, without which he cannot rule. A Macguffin Hunt begins throughout Mainland China while the Uncles try to stop violence from breaking out on the streets of Hong Kong.

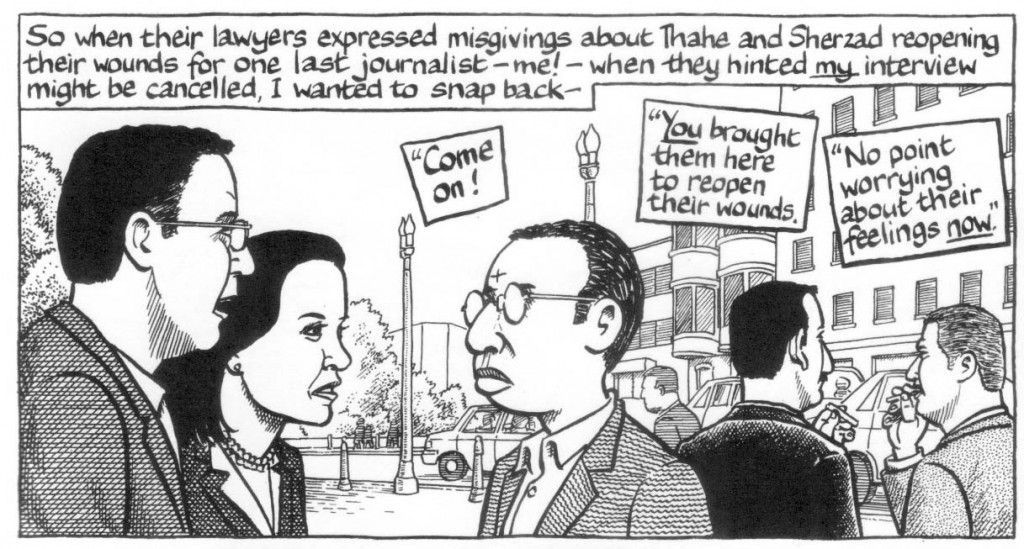

Louis Koo as Jimmy

I won’t spoil what happens next, as it all gets resolved in ways you wouldn’t expect and defy the western gangster conventions with which To is clearly enamored, but along the way we meet a few other key figures, including Jimmy (played by Canto-Pop idol Louis Koo), a businessman and mid-level Triad operative who just wants to make his money, Big Head (Lam Suet) a dutiful, tradition-minded dunce, Jet (Nick Cheung) a feral enforcer who obeys orders like a dog and Kun (Gordon Lam Ka Tung) an ambitious and violent soldier. Eventually, the hunt for the baton and the election dispute are resolved, paving the way for Triad Election.

In Triad Election, the same cast of characters returns, and it is two years later. The winner of the previous film refuses to step down despite the fact that the Chairmanship is a term-limited position. Meanwhile, due to his business dealings, Jimmy is forced to run for Chairman by the Mainland Security Bureau even though he wants to quit the Triad, which he only joined for protection in the first place. If the first film is a dark but often fun romp that unfolds in unexpected ways, Triad Election is a slow and violent descent into multiple kinds of personal hell, as the various players lose all they really care for—including their humanity—as their desire to win overtakes them.

Despite having the backing of big players like Quentin Tarantino, Election only received an art-house release in the US, while Triad Election (which is incomprehensible without the first film) received a wider release and, predictably, flopped. But thanks to Netflix Streaming, that Valhalla of the Worthy and Cheap to License, both are finally available in an easy-to-obtain form, and what’s more, like The Wire, they reward rewatching, as the films are densely packed, stylistically exquisite and nearly exposition free.

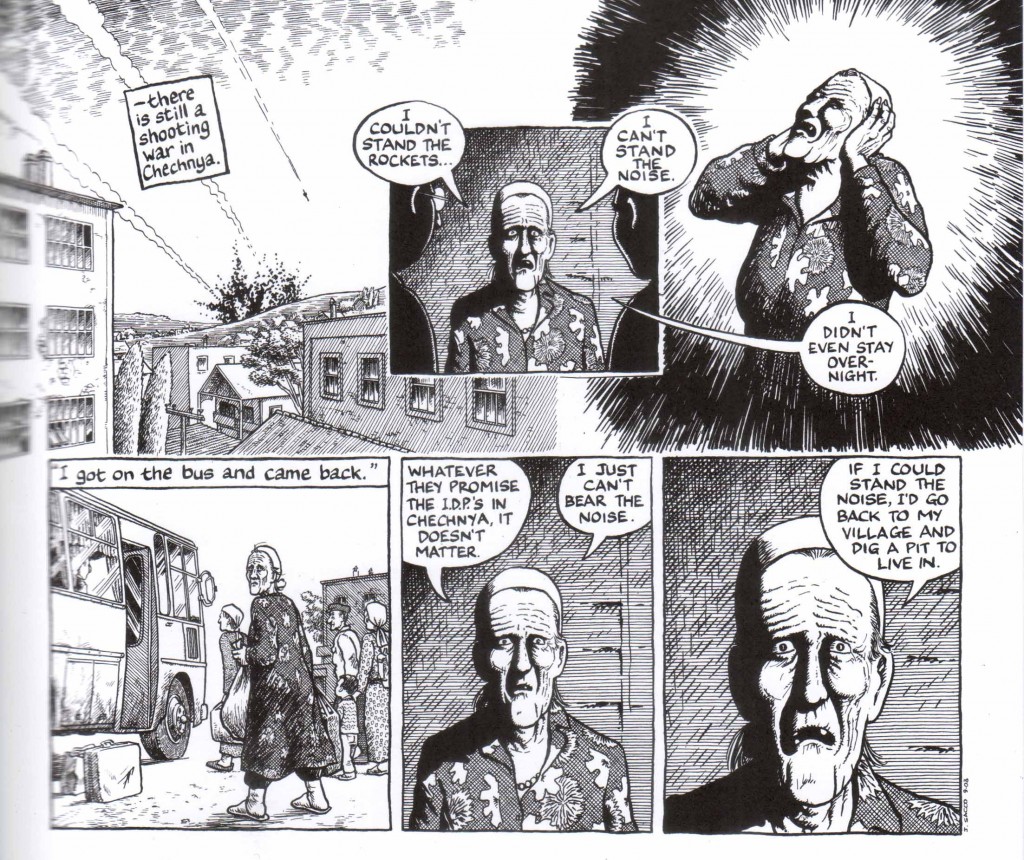

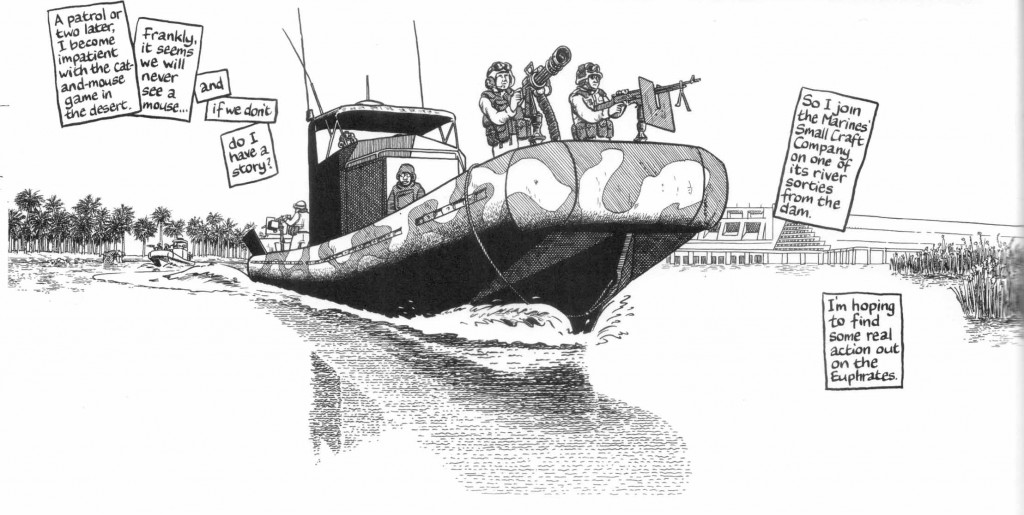

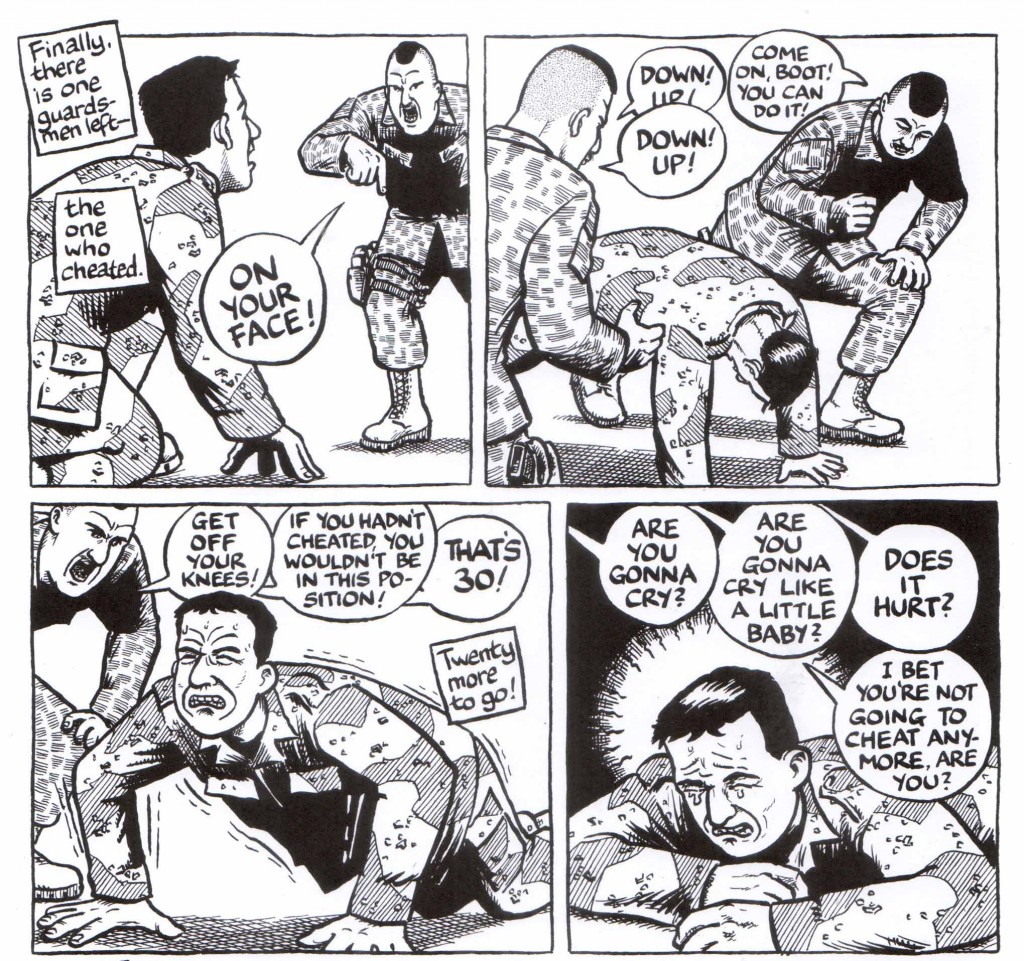

To’s visuals often place characters in heavy shadow, here we see

several of the Uncles gathered to discuss the vote

Many pixels have been spilled documenting David Simon’s perspective on our crumbling institutions of government. As he told The Believer, societal institutions are like the Gods in Greek Tragedy, inexorable, powerful forces that undermine individual agency. The truth teller in a Simon piece is always the head that’s eventually going to be on the block. Attempts to improve the overall situation are doomed to succeed only on a small level, and only for a brief period of time, but are still noble and worthwhile. Simon believes in individuals. Individuals may, in fact, be the only thing in which he’ll invest his faith. This forms a tension with his Democratic Socialist political leanings and this tension is part of what makes his work so electric and alive when it is at its best.

The perspective of the Election films inverts this equation. In To’s Universe, individuals are the problem and institutional tradition’s bulwark against individual will is the only thing standing between order and chaos. The problem in the Election films is that post-Millenial capitalism, with its empowering of individual will, embrace of selfishness, and temptations of money has eroded these institutions to the point where they are a hollow, symbolic shell. To makes this point again and again, most vividly in the first film when the chase for the baton climaxes in one Triad brother beating another with a log while the victim recites the oaths of the Triad, hoping (incorrectly) that they will protect him. The Hong Kong of Election is devoid of Bunny Colvins and McNultys and Daniels, it is instead a world where the sun is setting on an old guard who do not realize that their time is up, that “brotherhood” has become meaningless, that, to paraphrase one of the candidates, money is all that matters now.

The films are, then, an allegory that speaks to our present moment in America, despite being a violent realization of Reunification Anxiety. We live in a time where the series of “gentleman’s agreements” undergirding many of our institutions have completely eroded. We now need sixty votes to pass anything or appoint anyone in the Senate due to filibuster abuse. The various financial scandals—in particular the recent LIBOR manipulation—stem in part from relying on people choosing to do the right and honorable thing. One party campaigns on Government not working and then, when elected, ensures that it doesn’t. The open politicization of the Supreme Court has eroded its credibility to such an extent that the Military is now the only widely trusted public institution. The picture of our future painted by the Election films is a dark one. If anything, the films seem fairly convinced that we’re all doomed, that because we do not keep to our traditions democracy is on its way out and that business, aided by a corrupt government, will win every time.

This is not a worldview that I personally agree with, but then again, David Simon’s pro-individual-but-we’re-all-fucked-anyway cynicism grates on me too. Luckily, both works also contain rich strains of ambiguity and conflict. For example, the Uncles safeguarding the traditions of the Wing-Ho society are feeble old men, many of them easily bribable, dim-witted, and lecherous. We learn early on in a throwaway line that the last election for chairman was rigged. And, while To is oddly sentimental about Triad ways, pausing with stirring, nostalgic music to watch the old Uncles take tea together, using what were rumored to be real secret hand gestures in an initiation ceremony, some of this can simply be chalked up to To’s Michael-Mannish love of men manning up and being manly-men while also I might have mentioned doing man things, but sensitively.

To’s films frequently take place in a world that’s not-quite-ours. Exiled—a quasi-Western set in Hong Kong and Macau—replaces blood with red dust. The Mad Detective’s world is fractured, allowing fantasy and reality to spill into each other. Sparrow posits an underground of competitive pick-pockets in an elegant, swirling city that’s equal parts Hong Kong and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Throw Down takes place in a world where everyone knows Judo. In the Election films, there are no guns (one is held and waved around but never used). This lends the violence an excruciating visceral quality. Each assault (with rocks, logs, fists, hammers and, often, sabers) is fully felt by the viewer, even though the violence is (with two very important exceptions) visually restrained, choosing instead the tools of sound, shadow and your imagination.

Throughout, there are also little details that reveal themselves in later viewings. The way that Jimmy, the businessman and reluctant candidate for the Chairmanship, is the only lieutenant who knows the proper way to drink wine, and is first shown looking on with dismay as his desiccated boss commands a busty prostitute to jump up and down in front of him faster and faster. The look on Lok’s face when he learns he will be chairman that lets you know early on he’s not quite the modest hard worker he seems. The subtle, matter-of-fact camera work that lends the work a lean and mean economy. The way the propulsive drum-and-guitar score of the first film becomes a sparser, darker, atonal piano-and-strings affair in the second.

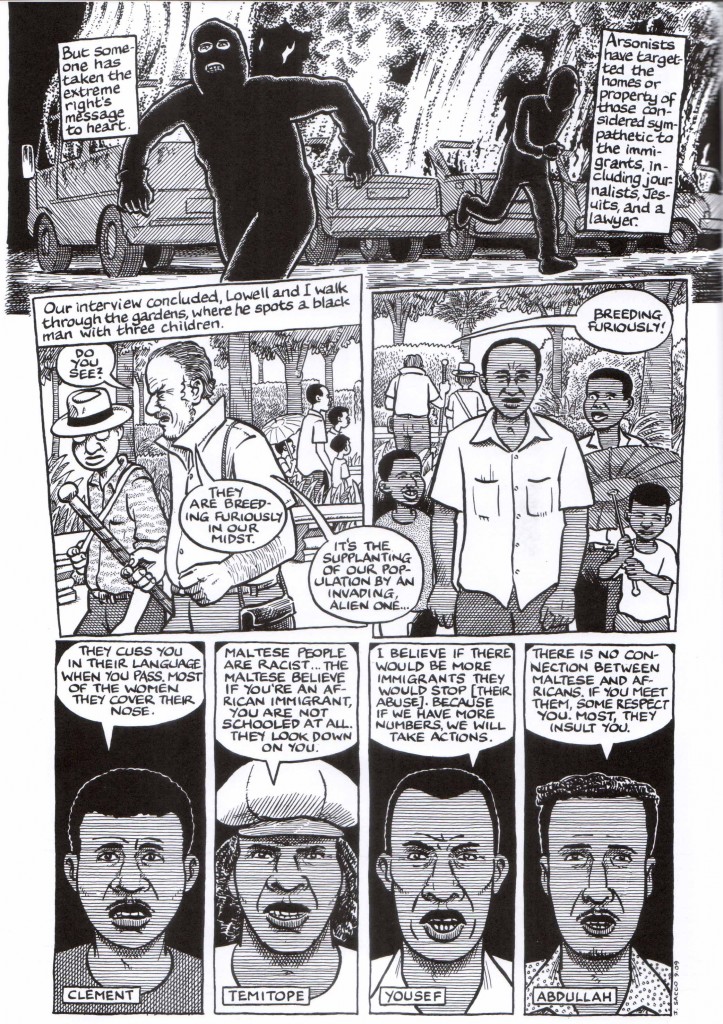

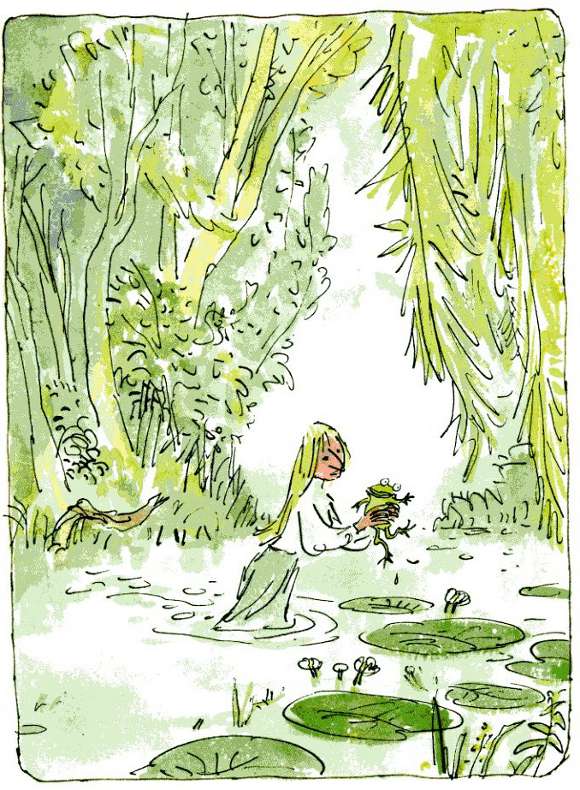

It’s easy to miss amidst everything else how beautiful many of To’s compositions are.

There is a part of me that is concerned that, by writing two pieces of breathless enthusiasm in a row for despairing entertainments about contemporary life, I’m both revealing biases I was heretofore unaware of and cutting way too far against the Hooded Utilitarian grain, but the Election films are, taken together, a dark-hearted masterpiece. Even thought they’re imbued with a nostalgia I don’t share for a lost time that almost certainly never existed, To’s mastery and reinvention of genre tropes are on equal display, and his ability to use pulp conventions to create a sweeping autopsy of the world around him is remarkable.