Once upon a time, there was a bastion of comics criticism which, it has been opined, stood against the hordes of barbarians trumpeting the works of John Byrne, Todd McFarlane and assorted other idolaters of caped beings. But time withers all, and like Saint Gregory of Rome, the rulers of that holy organ negotiated a separate peace with the hordes — the “empire” surviving but now a rotten shambles and a mockery of what it once stood for. It has been said that the purported ideals of that magazine never existed in the first place. That past is debatable, the present less so.

What was once a hotbed of disagreement and debate has now become one of affirmation and boot licking acceptance. The rallying cry heard last week was a sermon to the converted, an affirmation of the god-like status of various revered cartoonists — that their comics remain untarnished by dint of an indefinable comic-ness

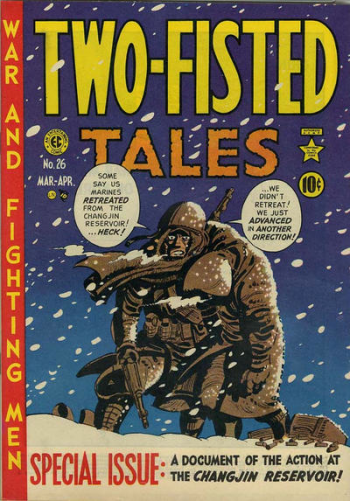

Like many rallying cries, Campbell’s piece is long on rhetoric but short on substance. His primary example as to the brilliance of the EC War line is the cover to Two-Fisted Tales #26.

“Some say us marines retreated from the Changjin Reservoir! …Heck!…we didn’t retreat! We just advanced in another direction!” – Harvey Kurtzman

“Let me fix the Kurtzman war comic in the reader’s mind before moving on. Here is the cover of Two-Fisted Tales #26, March 1952. There is a whole story in it and the way the story is told is quite sophisticated. A soldier in the middle of a historical action is already referring to it in the past tense. The first time I saw Kurtzman’s war comic art I wondered how on Earth he was able to get away with something so radical as that choppy cartooning, so far removed from what one would expect in war art…” – Eddie Campbell

Now Campbell gives my name quite a bit of play in his article. He mentions it again here as if I was denying Kurtzman’s skillful storytelling in certain stories done for the EC war line — as if no juice could possibly be pressed from mediocre fruit. I would ask interested readers to read the article he cites to see for themselves if I have denied Kurtzman’s talent for cartooning as Campbell’s hysterical pronouncements seem to suggest.

Readers not predisposed to give Campbell carte blanche might be slightly confused by the logic of his arguments. The second half of his article assails us with an example of a superior comic-ness which deserves praise, but his half-hearted readings of the EC war comics don’t match this aesthetic appeal and simply revert to typical descriptions of the narrative and the art—Kurtzman’s “choppy cartooning” and the questionable narrative genius of the cover illustration in question:

“…there is a whole story in it” with “a soldier in the middle of a historical action […] already referring to it in the past tense.”

The first question one should ask is why this is especially notable or the mark of a great talent for comics. Are the soldier’s words a prophetic utterance which lodges itself into the entire fabric of Kurtzman’s Changjin Reservoir issue, or is it a philosophical discursion on the paradoxical nature of time and fate?

For those not inclined to read the comic or use their brains, let me just say that the answer is “no” to both these possibilities My suggestions seem utterly ridiculous because the answer is plainly obvious to any reader who regards the cover as a whole. There can be little doubt that the illustration and narrative communicate the language of cover advertising and propaganda.

The disheveled fighting man carrying his wounded comrade; the brilliant brush work twisting and turning—melding the two into one single beast straggling across a snow swept battle field; defiantly disabusing all non-combatants and the foolish crowd of onlookers (journalists and naysayers) of the possibility of any lack of bravery or incompetence. This is not a place for cowards or laggards but one for heroes (misunderstood, at the bottom of the chain of command, injured, or dead), who are not fighting for any abstract concept but just to survive.

What Campbell’s statement suggest is a solitary interest in technicalities, and how this differentiates him from the fans who flocked to superhero conventions during comic’s early years, I’m not entirely sure. When it comes to the spiritual content of Kurtzman’s work, he seems quite deaf or purposefully blind.

Lodged within Campbell’s thin description are other questions —whether we should judge a piece of art as a whole or by its parts; and if we accept that art can achieve greatness purely on the basis of its narrative skill or artistry, is that artistry of a level that we can forgive almost everything else (McCay’s Little Nemo comes to mind immediately).

Kim Thompson latches on to this in the comments section and I quote:

“Complaining that a comic is no good because the story is no good is like complaining that water isn’t a good liquid because oxygen isn’t wet. Bravo, Mr. Campbell.” – Kim Thompson

Thompson’s metaphor is of course thoroughly imperfect since oxygen is frequently found in its “wet” state in our modern world but let’s see what he’s getting at here. In Thompson’s comment, comics are likened to water, which every elementary school kid is taught is composed of hydrogen and oxygen atoms. In other words, through the combination of art (hydrogen) and story (oxygen), a new, fastidious, and fabulous art form is created known as comics (water). This art form bears only a cursory relation to those things which constitute it and is neither art nor story but something entirely new which obeys no “laws” of aesthetics except those which are conjured up in the rectum of Eddie Campbell (and, maybe, his editor Dan Nadel).

Of course, this line of thought is irrelevant if one assumes that a cartoonist-critic is interested purely in the utilitarian aspects of the art in question. If one simply wants to emulate Kurtzman’s drawing line or his almost extradiegetic storytelling, the absolute quality of the art in question is extraneous.

If we mean to be “critics” interested in the formation (or reassertion) of a canon, then the absolute aesthetic appeal of a comic takes on more importance. This was certainly one of the motivations behind The Comics Journal‘s Top 100 comics list (where the EC line plays a prominent part) — a list mired in the concept that as the roots of comics reside in degradation and populism, they should conform to and be judged by those criteria only. As such, when The Comics Journal Top 100 comics list was produced, it was not so much an exercise in choosing comics of artistic merit but a process of choosing the best smelling shit — shit which, presumably, has no relevance or connection to the world at large.

Campbells’ other argument for the genius of the EC war comics comes at the close of his piece:

“If comics are any kind of art at all, it’s the art of ordinary people. With regard to Kurtzman’s war comics, don’t forget that the artists on those books were nearer to the real thing than you and I will ever be. Jack Davis and John Severin were stationed in the Pacific, Will Elder was at the liberation of Paris. Maybe we should pay attention to the details.”

In this, he trots out an age old argument in buttressing these comics — their authenticity. And who can doubt this? For participation in war and killing (voluntarily or involuntarily) is self-legitimizing — the only truth when it comes to battle. The entire fighting corpus is like a single amoeba with a single mind and a single all-encompassing viewpoint. And why even consider the enemy, the dead, the relatives of the dead, or those who oppose war? Can a cartooning genius ever be limited in his vision or politics? Can he ever be sentimental and derivative? Can a cartooning genius ever be wrong?

_____

The other points in Eddie Campbell’s article will be dealt with in the rest of the roundtable.