This first ran on Splice Today.

___________

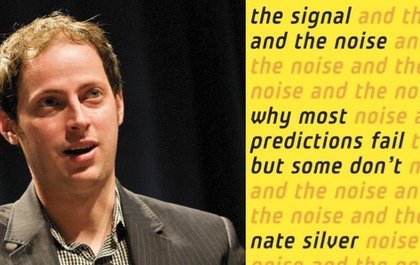

Nate Silver’s The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail — But Some Don’t appears, at first glance, to be a guide to better wonkitude. In fact, though, it’s something of considerably more interest — an argument for how and why predictions are central to creating a better world. The good is predicated upon good prediction — which means that (though Silver never explicitly says as much) forecasting is not just a skill, but is a moral act. The Signal and the Noise, then, somewhat surprisingly, is as much a guide to ethics as a guide to statistics — or, perhaps more accurately, is a guide which suggests that you cannot do ethics without statistics, and vice versa.

Silver is best known for his political prediction site, fivethirtyeight, which has become legendary over the last four years for its success in calling Presidential and Senate elections. He’s also well known for using baseball statistics to predict player performance, and or his moderate success as an online poker player. Silver spends time discussing all of these endeavors, None of these endeavors seem to have much of a moral content — but Silver’s book also focuses on other venues for prediction where the virtue of getting things right translates more easily into virtue, period. Predicting hurricanes, earthquakes, or terrorist attacks all have obvious and large scale effects on many, many people. Similarly, evaluating the probability of climate change is hugely important for just about everyone on the planet.

How, then, can we improve predictions? Silver offers a number of suggestions — but the most important boil down, perhaps, to a willingness to acknowledge how hard it is to improve predictions. Silver divides forecasters into two groups: hedgehogs and foxes. Hedgehogs for Silver are people with a single big idea, which they stick to tenaciously. Foxes, on the other hand, are uncertain, eclectic, and willing to change their minds. Hedgehogs have grand theories; foxes limited hypothesis. Hedgehogs believe in their models; foxes don’t trust theirs. Hedgehogs pronounce and then confidently demonstrate how the data fit their pronouncements; foxes look at the data first, and then, cautiously and with many reservations, try to see if there is a pattern.

Hedgehogs, Silver argues, are more likely to be interviewed on talk shows or get quoted in the press, because they’re the ones likely to make shocking and exciting predictions that garner big headlines. You’re more likely to sell books if you declaim that the US will definitely face a major flu pandemic in the next 10 years which will kill millions. But you’re more likely to be right if our claims are less ostentatious and more foxy — if you admit, for example, that flu pandemics are hard to predict, and that the likelihood of a deadly outbreak is tricky to measure with certainty, which is why (as Silver reports) many flu scares in the past have failed to pan out.

Foxes, Silver says, need in particular to acknowledge and understand their own biases. The idea here is adamantly not to eliminate biases, which Silver suggests is impossible, and probably not even desirable. Instead, it’s to make explicit where the forecaster is coming from — to figure out what the forecaster is assuming (based on common sense, expert knowledge, rules of thumb, or even rank ideology) before she makes her prediction.

This is in part why Silver (and most other statisticians) advocate Bayesian reasoning. In Bayesian reasoning, a forecaster begins by stating her own estimate of an events probability, and then adjusting that probability on the basis of subsequent evidence and events. Bayesian reasoning, in other words, forces a forecaster to admit to her own prior biases, and then test those biases against what actually happens.

To be a foxy Bayesian, then, is to be possessed of humility and honesty — particularly self-honesty. These are obviously important virtues in most moral systems, and Silver is entirely convincing when he claims that they are vital to the art of prediction.

A funny thing happens, though, when humility and honesty are instrumentalized as part of the predictive process. Specifically, it ceases to be clear that humility is humility, that honesty is honesty, or that either are particularly virtuous. Thus, for example, Silver’s enumeration of the virtues of foxes is pretty clearly an enumeration of his own virtues — he is the fox, pointing out the flaws in all those arrogant hedgehogs. This isn’t necessarily a problem for his arguments per se — but it does give that section of the book an unpleasant air of self-vaunting.

More consequential, perhaps, is Silver’s discussion of the great poker player Tom Dwan. Silver is clearly extremely impressed with Dwan, and singles him out as an exceptionally good poker player — which means, specifically, an exceptionally honest one. Dwan “profits,” Silver says, “because his opponents are too sure of themselves.” Dwan, on the other hand, is great in large part because he knows how great he isn’t. “‘Poker is all about people who think they’re favorites when they’re not,'” Silver quotes Dwan as saying. “‘People can have some pretty deluded views on poker.'”

So, again, Dwan’s strengths are the virtues of honesty and humility — and he uses those virtues to make a living by preying on the weak. Silver explains that the weakest players in poker support all those above them in the pecking order. If you’re making money in poker, it’s almost certainly because there are people in the game who don’t know what they’re doing — who think they are far better than they are, who are deluding themselves, who don’t know how to play. Dwan’s virtues — and Silver’s, when he was playing poker professionally — allow them to make rational predictions, and thereby to systematically take advantage of the less virtuous/clever. Improving predictions here seems less like a way to improve the lot of humankind, and more like a way to create a more perfectly rapacious capitalism.

“Presuming you are a betting man, as I am,” Silver writes at one point, “what good is a prediction if you aren’t willing to put money on it?” It’s a telling formulation, seamlessly linking money, predictions, and goodness. For Silver, the sign of virtue and value is money — the marker of success. Honesty and humility are worthwhile because they lead to results — and you can measure those results best through cash.

The problem here is not that Silver is wrong. On the contrary, the problem is that he’s right. His moral vision is, for all intents and purposes, the moral vision that matters. His algorithm — greater virtue -> progress -> good-certified-by-money — is as close to a consensus ethical vision as we’ve got. Refine our tools, increase our knowledge, improve our lives, if only incrementally. That’s how modernity works.

It’s certainly an attractive vision, and not one that anyone can oppose categorically. Who wouldn’t like better foreknowledge of earthquakes or disease outbreaks? Yet, at the same time, it might be worth remembering that controlling our lives and living a good life are not necessarily the same thing. They can even, in some cases, be opposed. A world of foxes is not a heaven if those foxes are all intent on devouring each other. Silver would be the first to say that we will never know the future. His solution — and it is a moral solution — is that we should work hard at predicting it just a little better and a little better. Perhaps, though, in addition to becoming more and more powerful predictors, we might devote some time to thinking about how, in a world where our future is uncertain and our power limited, we can best treat each other not as foxes or hedgehogs, but as human beings.

(On morality and virtue, with an incongruous sprinkling of modern television drama)

Great post as usual, Noah. You do your best work on morality — well, and teenybopper pop music — and fetishism in early Wonder Woman comics, of course. You have an eclectic array of strong suits.

The issue in your article is being “good” versus being “good at it.” The comparison reminds me of a scene from The Sopranos, wherein Dr. Malfi questioned why she was treating Tony. Was she merely making a more well-adjusted, and therefore more able, gangster?

Virtues are not virtues just because someone said so, but because they’re a more effective way to live. Self-honesty, humility, and even adeptness at statistical analysis are admirable traits no matter the purpose to which they are employed. For that matter, so are industriousness, discipline, courage, discernment, loyalty, courtesy, conscientiousness, and eloquence. But several virtues on my list could be applied to leading members of the Third Reich, and they still weren’t good people. This is what made the Nazis (and every villain on 24) so dangerous, so unusual, and so scary. It wasn’t just the depth of their evil, because lots of people are as evil as the Nazis were. It was also the height of their virtue, because it made them so effective. Most real world bad guys just aren’t virtuous enough to do that kind of damage. That’s why they become bad guys. If you have all those virtues, you can probably get what you want without hurting anyone and risking negative consequences, at least in the world’s nominally functioning societies. Well, you can as long as hurting people isn’t your end goal — hence, Nazis.

The genius of egalitarian societies that enable social and economic mobility is that they allow people to pursue happiness within the rules and norms of society. Thus, the biggest motivator for aberrant behavior is largely removed. Obviously, circumstances and perceptions vary, so there are still chemistry teachers who decide the best hope for caring for their family’s well-being is to produce high quality crystal meth in volume (Breaking Bad is a documentary, right?). But assuming a rational actor model, most of us decide most of the time that doing the right thing is more effective. In addition to genuine concern for others, fear of guilt, fear of social opprobrium, and fear of punishment, I can more easily make extra cash by working overtime than can by holding up a liquor store. I am also more likely to achieve social status I will enjoy by being an interesting, caring, likable person than by poisoning the other members of the royal court. Those facts change the decisions I make.

This is an extension of the natural action and consequence system operating in the universe. You can be Al Capone if you want, and you may enjoy it for a while, but there’s a good chance you’ll die in prison of syphilis. You can come home in a bad mood and take it out on your family, but it will only cause you more pain in the long run.

If one is a theist, like I am, one might believe that God laid down rules of behavior out of concern for humanity, knowing that adultery, thievery, and murder, for example, cause suffering for both the perpetrator and the victim. The rules against such behavior are therefore like rules against playing in the street. One may also believe — alternately or simultaneously — that God uses the rules to teach us about his own character (“his,” for lack of a gender neutral personal pronoun). From this perspective, the natural consequences of our actions are merely art reflecting the artist. This is true not only of the negatives, but of the positives, like “love thy neighbor,” “care for the sick,” “give to the poor,” “visit those in prison,” and “return good for evil.”

Going back to the use and abuse of virtue, the most difficult virtues to turn toward wicked ends are those that demonstrate, or perhaps presuppose, the inherent value of other human beings. These virtues — kindness, generosity, graciousness, forgiveness, mercy, and faithfulness — are demonstrated by the positive injunctions above. They are also summed up in a single word from Jewish scripture, hesed, often translated “lovingkindness.” Hesed, then, is the most virtuous of virtues.

Others are also foundational, even if more prone to misuse. Discipline is remembering what you want most and acting in the matter you believe will achieve that goal, despite temptations otherwise. Correctly judging what behavior will achieve your goal is a kind of wisdom, and a higher wisdom is knowing what goals are worth pursuing. If one pursues discipline and wisdom, other virtues start appearing like weeds in the garden. If one simultaneously strives toward hesed, the odds that one will misuse those virtues plunge, returning us to predictive analysis. That’s just my bias, though, and I have no statistics to back it up.

I’ll continue my unsupported moral assertions thusly: Generally speaking, the way to provide the most benefit for the most people, including ourselves, is to act in a manner that is as close to objectively good as we can discern. That’s not to say that we are not sometimes punished for our good deeds and rewarded for our bad ones. It happens, but it doesn’t disprove the general rule, anymore than a man dying while jogging proves that exercise is bad. When these perverse incentives occur, they are evidence of disfunction, whether they are in a family, a profession, an economy, or a legal system. Disfunctions like that often have far-reaching, even catastrophic negative effects. The recent recession is the example that springs to mind, but there are many others.

So, in closing, virtue can be used for evil and still be virtue. Love, wisdom, and discipline are worthy pursuits. Altruism is merely enlightened self-interest, at least most of the time. And when it’s not — well, I remember one of my college instructors. He was “visiting” academia teaching us when he discovered he would not be able to return to his formerly promising career. He had blown the whistle on unsafe working conditions that had caused several deaths. His excommunication was most likely a reprisal. The last thing he said to us as he gave us the final was, “There will come a time when you are faced with a decision, and doing the right thing will cost you dearly. Do it anyway.”

I was reading the Gospel of Luke (well, my pastor gave a sermon on it) today– and Jesus is telling the Pharisees at a banquet never to invite their equals to a banquet– not to refuse invitations they receive, but only to invite the most impoverished and rejected, because there can be no hope or thought of reciprocity. Which is something of a blow to the egalitarian community of Kantian rational actors. And questions the soft-power humility of Nate Silver’s freakonomics.

Yeah…an ethical system which is about identifying with the weak and the victims is pretty definitively different than an ethical system which is about being humble as a mechanism for greater efficiency.

Silver is less annoying than the freakonomics guys I think because he’s not gleefully contrarian? That is, his main targets are idiot political pundits who pretend they know what they’re talking about, rather than foolish people who think morality should matter. Not that it’s unfair to lump him in with them, really…just that (as a kind of comment on morality) there is something to be said for not willfully being a dick.

And…wow; that comment is almost as long as the essay, John!

I think your comment, and the essay, maybe get at some of the tensions between utility and morality…or maybe within utility? Utility as a moral system generally looks for the greatest happiness for the greatest number — but it also, obviously, has strong connotations of, or intimations of, efficiency and workability.

I don’t think it invalidates altruism as self-interest, though. Jesus actually encourages that viewpoint. In the passage in Luke you’re referring to, he’s advising his host to avoid earthly reward in favor of repayment “at the resurrection of the righteous.” In Matthew 6, he similarly advises that prayer and fasting should be done in secret, and not for public display, so that the reward will come from God and not men. Luke 6 shows why this is a better deal. “Give, and it will be given to you; a good measure–pressed down, shaken together, and running over–will be poured into your lap. For with the measure you use, it will be measured back to you.” I think the message is that God rewards more generously than men, in this life and especially in the next. That doesn’t seem very spiritual, because it’s certainly not pure selflessness or asceticism, but it helps me do the right thing sometimes. It’s a morality that accounts for human nature. Confronted with the standard Jesus both lived by and advocated, I will take any break I can get.

Eh, this seems like kvetching for the sake of kvetching — which, granted, is the reason God created the internet, but still. This, for instance:

“Presuming you are a betting man, as I am,” Silver writes at one point, “what good is a prediction if you aren’t willing to put money on it?”

seems less like a telling formulation by Silver, and more like a willful misreading by you — which, granted, is the reason God created the Hooded Utilitarian, but still. I haven’t read the book, but the obvious interpretation of “good” here is “useful”, without any moral valence intended. To which, I imagine, your reply would be that that’s precisely the problem, but the use of “good” here to mean “good from the perspective of practical reason” is a perfectly ordinary usage, not at all confined to “modernity”. (e.g. “What good is a can of baked beans without a can opener?”) If this is the best you can do for a smoking gun, it’s weak sauce.

Mmmm, smoking gun with weak sauce.

Unless he’s an idiot, Silver presumably wouldn’t say that predictive power is sufficient to determine morality. Presumably what he’s saying is that it’s a necessary condition, which even the most diehard anti-consequentialist would agree with. To complain that therefore a book about prediction is not a book about morality is like complaining that it’s not a cure for cancer. You can’t do everything all at the same time.

I think the use of good goes both ways here…and yeah, that is the point I’m making.

I don’t really think that’s the smoking gun, though. The smoking gun is his admiration for the superb poker player, his explanation that said superb poker player makes his living by preying on the weak, and the failure to allow that second point to influence the first.

Furthermore…I’m not complaining that it’s not a book about morality. I praise it because it absolutely is a book about morality. I’m complaining because I don’t entirely agree with the moral system put forward.

But…you should read the thing and write about it for us, Jones. I bet you’d have really interesting things to say about it.

Noah, my last comment was a response to Bert. Response to your comments follow: “There is something to be said for not willfully being a dick.” Amen, always and forever. That’s courtesy or gentleness — more hesed virtues that reflect a belief that human beings have inherent value. I dealt with someone today who rejects your philosophy, and seeing him in action only affirmed it for me.

Yes, your essay got at the tensions between utility and morality, which inspired (Nay — COMPELLED!) me to respond. Sorry, I’ve been reading Walt Simonson’s work on Thor, and it’s affecting my diction. Anyway, one of my points is that doing the right thing leads to the most good for the most people. I think utilitarianism tells you that whatever does the most good for the most people IS the right thing. It’s an algorithm to find the right thing to do. The difference is between cause and effect, or maybe effect and indicator, and it may be circular. I would argue that the right action is whatever action expresses the greatest value — even reverence — for God and the cherished masterpiece of his creation, humanity. This goes back to what Jesus said were the two greatest commandments of God, both from the Torah: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and all your soul, and all your strength, and all your mind,” and “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

I didn’t mean to turn this into Sunday School, but when you bring up morality, I do it every time, so I can’t act like it’s an accident. You should all be thankful I leavened the churchiness with the mention of a pagan god.

Regarding the length of the comment: Yep, it was long. I don’t know if that’s good or bad.

Also, I thought about applying this “inherent value of human beings” argument to the torture debate over on the Zero Dark Thirty post, but didn’t have the energy to wade into what was already deep water. In summary: “Ticking time bomb” scenarios actually do happen. When they do, the issue becomes which values humanity more, performing repugnant acts for a chance (only a chance) at saving human life? Or forgoing the suffering and indignity that will be forced upon not only the detainee, but his interrogator? Thomas Jefferson wrote some keen insights on the negative effects of slavery on the slave owner, and I think they apply in this case, too. That said, we (the American people, through our government) do a lot of ugly, even repulsive things because we believe they are the right thing to do — kill people, imprison them away from their home and everyone they love, take away hard-earned property, threaten them with longer sentences if they don’t give up their co-conspirators. That last one, by the way, might qualify as “mental coercion” under the Geneva Convention. I’d have to look this up, but I don’t think that international law ever uses the word “torture,” just “physical or mental coercion.” Anyway, are all of those things wrong? Or are they sometimes right because of what they accomplish? If they are ever right, is torture in a ticking time bomb scenario different? I don’t know. I know I wouldn’t ever want to be faced with the decision.

Jones, regarding “the reason God created the Hooded Utilitarian,” is this your intimation that everything in the universe is an outgrowth of God’s vast deterministic plan, or are you saying that Noah is God?

I’m envisioning a heretofore unexpected heaven where Harry Peter’s work is exalted far above that of Jack Kirby. Repent, ye trolls…

Nah…I like Jack Kirby better than Harry Potter. Jack Kirby I’m mixed to positive on; Harry Potter is mixed to negative.

I think our current prison regime is pretty evil. Same for plea bargaining, actually (though not to the same extent.)

Harry PETER, Noah! Wonder Woman!

John, I absolutely have no ready comeback– if you are willing to appropriate “Love God and your neighbor” as utilitarian dogma, I’m sort of baffled, although sympathetic. I do think that acting on behalf of questionable institutions has fouled up large-scale utilitarian decision-making since the days of Jeremy Bentham (I know he was a feminist and everything), and can lead to what Noah has memorably termed bean-counting after the apocalypse. But I greatly appreciate your thoughts.

Hah! It is Harry Peter! I misread it. That’s so funny.

But yes; Harry Peter is better than Jack Kirby, damn it.

Bert, I’ll take baffled, but sympathetic. I could have inspired far worse reactions. Thanks for pointing that out to Noah, by the way. I couldn’t tell if he was putting me on or not.

Ha, thanks Noah, but I doubt I’d have anything interesting to say about what sounds, from all accounts, like a book on Bayesian practical reason. Besides, it’s too tiring to discuss morals with you; you can move the goalposts much, much faster than I can kick the football.

Harry Peter is NOT better than Jack Kirby. NOTHING is better than Jack Kirby. Nothing.

I don’t think it’s fair to accuse me of moving the goalposts just because you’re not aiming at them….

I will add one thing, to Bert: criticising utilitarianism for “acting on behalf of questionable institutions” while advocating for a Christian-based ethic is…well, I dunno your own personal convictions, but it seems like, when it comes to acting on behalf of questionable institutions, there’s plenty of beams to go around for the eyes of monotheists.

“In summary: “Ticking time bomb” scenarios actually do happen.”

Where exactly do these scenarios happen? I mean, besides inside the minds of authoritarians.

In reality, the real-life scenarios where something of that sort would actually happen are so rare and/or nonexistent as to make them useless for logical arguments. So from there we have Scalia justifying nationwide strip searches by using Mohammed Atta as a counterexample.

Oh, have Christians done horrible things? I really must try to do more homework.

You see, though, Christians, lots and lots of them, can actually say that burning witches or molesting boys or pillaging the Middle East is bad. I would be quite glad to see examples of utilitarian autocritique.

sorry, bert, i was aiming for the goalposts around condemning moral theories that have been used to prop up corrupt institutions and practices. I’ll have one more kick at these new goalposts, and then I’ll have to go. Like I said, it’s too tiring; I don’t want to give myself a heart attack. (seriously — no hard feelings, but life is too short and i’ve done this often enough here to know that each side will make zero progress)

Not 100% sure what would pass as “utilitarian autocritique” but…two minutes on google (i havent read any of these, admittedly, so I can’t really vouch for them):

http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/jscope/arrigo03.htm

http://www.alternet.org/story/41648/the_myth_of_the_ticking_time_bomb

http://digitalcommons.law.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=jurisprudence

http://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2012/10/why-was-hobsbawm-wrong.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14959723

if “utilitarian autocritique” means utilitarians criticising other people’s utilitarian arguments and reasoning, that’s all utilitarians do all day, when they’re not criticising non-utilitarians. that’s all philosophers do all day — sure, they criticise their opponents but they also love to criticise their fellow travellers for getting it not quite right. Put any two utilitarians in a room together and you’ll have at least three different versions of utilitarianism.

i.e. there are more things in utilitarianism than are dreamt of in your philosophy

Jones, I’m curious as to where we’re supposed to progress to…?

Well, just to take your internet salvo at face value, Horatio, we have a couple things about torture not being practical, Communism not being practical, and involuntary extension of life not being practical. Admittedly, the A-bomb scenario is mentioned in the “Stumbling” link, which is one of the more impressive (and well-publicized) utilitarian calamities, but I’m not completely impressed that utilitarians were criticizing demagogues. That’s what they/you do, I get that.

Fair question, Noah. I’m not sure what would count as progress from your POV — maybe if I repented of my arrogant ways, became an atheist Christian, and accepted full responsibility for the holocaust, slavery, racism, the bay of pigs, seth macfarlane, airplane food, the kids who picked on you in fifth grade etc.

From my POV, progress would be us meeting in the middle: you guys would stop being so smugly dismissive of a complicated and nuanced ethical tradition, and I would get to say “i told you so”. Ideally, you’d also start following Proposition 7 of the Tractatus, but let’s be realistic here.

PS: Bert, shouldn’t you be Horatio given my allusion? I win the internet!

But…my piece here is hardly a foot-stomping denigration of Nate Silver. I like Nate Silver! I really do praise him for being a moralist. I’m not dismissive at all, I don’t think; I try to figure out what he’s saying, point out where it seems reasonable, and point out where I disagree. I mean, you’re being way more dismissive here in comments than I was in the piece, as far as I can tell? I mean…read the last paragraph again?

“It’s certainly an attractive vision, and not one that anyone can oppose categorically. Who wouldn’t like better foreknowledge of earthquakes or disease outbreaks?”

That doesn’t seem dismissive. That seems like, “there are good things about this and then maybe there are some problems.”

Along the same lines:

“accepted full responsibility for the holocaust, slavery, racism, the bay of pigs, seth macfarlane, airplane food, the kids who picked on you in fifth grade etc.”

I would say that utilitarianism has things to answer for in terms of both the holocaust and slavery, yeah (though Christianity certainly does too.) Would you deny that? Or, if not that, is there any evil you’re willing to attribute to utilitarianism? Our prison system, maybe?

Oh…and that’s really funny that as a utilitarian your definition of progress is meeting in the middle. That’s not really what I see as the point of discussion. Rather, we chat, we enjoy each other’s company, maybe one or the other of us learns something. That’s good enough for me.

So are you trying to sell us on the ethical but not the supernatural aspects of Christianity? And why is this site called the Hooded Utilitarian?

My problem with the “first, love God; second, love your neighbor as yourself” teaching is that it sets a very clear priority that leads to incidents like the “difficult” story of Abraham and Isaac. In a totalitarian regime a little hypocrisy and corruption can be a humanizing mercy.

“So are you trying to sell us on the ethical but not the supernatural aspects of Christianity? And why is this site called the Hooded Utilitarian? ”

I don’t think I’m trying to sell anybody on anything in particular.

The title of the blog is a stupid one-person-injoke referencing a prose poem I wrote a long time ago.

the bit about meeting in the middle was meant as a joke (since “the middle” meant you admit that i’m right about everything, and i agree with you — this only counts as the middle if you’re a current Republican member of congress)

i always wondered why the title

———————-

John Hennings says:

…I think the message is that God rewards more generously than men, in this life and especially in the next. That doesn’t seem very spiritual, because it’s certainly not pure selflessness or asceticism…

———————–

Which reminds of the excellent point by, of all people, Dr. Wertham (who it’s now been discovered, faked and twisted info for his anti-comics case: http://www.bleedingcool.com/2013/02/11/dr-frederick-wertham-lied-and-lied-and-lied-about-comics/ ), that “crime doesn’t pay” reflects a morally ignoble attitude. “You shouldn’t beat up little girls because it doesn’t pay, but because it’s wrong.” (Quoted from memory.)

———————-

John Hennings says:

…Virtues are not virtues just because someone said so, but because they’re a more effective way to live…

———————–

“Effective”? They can be beneficial for a society. Honesty, not cheating on one’s spouse, carefulness to avoid hurting others can avoid all matter of damaging consequences.

There is plenty of moral behavior programmed in by nature; which causes animals, very young children, to behave altruistically, even in situations where it’s of no direct benefit or even to their personal detriment.

————————

The Yale Infant Cognition Center is particularly interested in one of the most exalted social functions: ethical judgments, and whether babies are hard-wired to make them. The lab’s initial study along these lines, published in 2007 in the journal Nature, startled the scientific world by showing that in a series of simple morality plays, 6- and 10-month-olds overwhelmingly preferred “good guys” to “bad guys.” “This capacity may serve as the foundation for moral thought and action,” the authors wrote. It “may form an essential basis for…more abstract concepts of right and wrong.”

The last few years produced a spate of related studies hinting that, far from being born a “perfect idiot,” as Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued, or a selfish brute, as Thomas Hobbes feared, a child arrives in the world provisioned with rich, broadly pro-social tendencies and seems predisposed to care about other people. Children can tell, to an extent, what is good and bad, and often act in an altruistic fashion. “Giving Leads to Happiness in Young Children,” a study of under-2-year-olds concluded. “Babies Know What’s Fair” was the upshot of another study, of 19- and 21-month-olds. Toddlers, the new literature suggests, are particularly equitable. They are natural helpers, aiding distressed others at a cost to themselves, growing concerned if someone shreds another person’s artwork and divvying up earnings after a shared task, whether the spoils take the form of detested rye bread or precious Gummy Bears…

—————————

http://www.twylah.com/SmithsonianMag/tweets/281507115519074304

But for immediate personal benefits, lying, conniving, stealing, cynical manipulativeness, amorality can gain one plenty of the “success” that is so valued by this society.

A business owner on “Personal Morality vs Business Morality,” argues that:

————————

Corporations cannot behave according to common human morality, because they are accountable to different systems. They must create profits simply to continue existing against entropy. Understand, they must maximize profit in the way we must breathe…

As a business person, you need to have a second set of morals. Your business morality should look to profit maximization above all else.

We have representative governments to impose moral order on the market…

The market tells you the way the world actually works.

The beauty of the market is its amoral nature. We aren’t accountable to other people’s ideas of what we should be spending our money on.

Understand, when McDonald’s competes for your dollar, it is competing against hookers, drugs, and booze. Any morality it emanates has been engineered to extract more profit.

————————-

http://www.kpkaiser.com/entrepreneurship/personal-morality-vs-business-morality/

Yes, it’s up to the government “to impose moral order on the market.” And if we have a certain Party that wants to “bring business methods into government,” guess what happens?

———————-

John Hennings says:

Self-honesty, humility, and even adeptness at statistical analysis are admirable traits no matter the purpose to which they are employed. For that matter, so are industriousness, discipline, courage, discernment, loyalty, courtesy, conscientiousness, and eloquence. But several virtues on my list could be applied to leading members of the Third Reich, and they still weren’t good people…

——————————

That’s because all of those aren’t necessarily morally virtuous. For instance, can’t a murdering brigand or Hun be disciplined, courageous? Loyal to their group? A Third Reich technocrat be industrious?

The prose poem in question is here. You can just search for “hooded utilitarian” if you’re interested; no need to read the whole thing (a fate worse than death!)

The level-headed Jones appears to have exploded in an effluence of witty, confident non-response. I wonder which one of us is smug, I smugly reflect.

Abraham and Isaac is a weird story, but it makes more sense in the historic context of living among people that actually did sacrifice children. It is a story about faith commitments, but also a story about not killing children.

What would be different, though, if Abraham were to make calibrated ethical decisions based on the welfare of the majority of people? Certainly the people sacrificing children were already thinking that way. Oh, if only they could have qualified their bias with Bayesian analysis.

I love Noah’s prose poem, I forgot how much.

Noah: “I don’t think I’m trying to sell anybody on anything in particular.”

Oh, come on. Of course you’re trying to persuade your audience of something. I’ve always gotten the impression that belief is part of the Christian package, and Christians like C.S. Lewis and it seems your Stanley Hauerwas are very clear about not separating out the miraculous in that Jeffersonian, pick and choose kind of way. Is that what you’re advocating, or what then?

“The title of the blog is a stupid one-person-injoke…”

But it seems like you’re pretty consistently down on utilitarianism…? The title always reminded me of Hooded Justice from Watchmen, but if anything it seems like John Hennings is being the hooded utilitarian here.

Bert: “Abraham and Isaac is a weird story, but it makes more sense in the historic context of living among people that actually did sacrifice children. It is a story about faith commitments, but also a story about not killing children.”

But the faith commitment for which Abraham is tested and specifically praised is his ability to kill his child on God’s say-so. Otherwise, what is his test? It’d be about not killing children if, for example, Abraham traveled all the way to the mountain and dramatically decided, “you know what? No!” and God said, “Congratulations, that was your test! I don’t want my servant to be some nut!” Abraham: “OMG, you had me going,” etc.

As it is, the story is promoted today, after a context of widespread child sacrifice, and Abraham is promoted as an ideal. That’s irresponsible. It’s not only literally to do with child sacrifice, it promotes a mindset: put your ethics and human feelings on hold in service of your religion.

“What would be different, though, if Abraham were to make calibrated ethical decisions based on the welfare of the majority of people? Certainly the people sacrificing children were already thinking that way. Oh, if only they could have qualified their bias with Bayesian analysis.”

This is a problem of reality. If you live in a universe governed by gods who can be influenced by sacrifices, there are situations of community survival where a leader’s sacrificing his child might make sense. But if that’s not how the universe works, he’s just a nut. That’s why I’d rather not get all postmodern about unitary truth and empirical evidence, but ground decisions about climate change, nuclear arms buildup, and God caring about a stretch of land in the Middle East, in what we know.

Didn’t Noah say he doesn’t think the magisterial Hauerwas would think real Christians could get involved in running a state? A job that has demanded weighing least evil outcomes for its entire existence. But we do live in a state system, and if he has an alternative in mind I’d like to hear it. I’d rather live in a state with leaders making decisions based on empirical evidence and best possible outcomes than leaders who idealized a faith-based, teleological suspension of the ethical and were passionately trying to reach that golden paradise just beyond the veil.

I don’t really think blogging or discussion has to be about conversion. But that’s me.

It sort of depends on the state in question, doesn’t it? And on your place in it. US leaders were making empirical decisions and so forth when slavery was around. Those decisions also resulted in our prison system, which is pretty thoroughly unjust. On the other hand, Quaker communities are faith based, and they don’t seem especially unjust by world-historical standards (which isn’t to say they’re just; world-historical standards are a pretty low bar.)

I feel like these discussions of reality based governing tend to be based on largely mythical governing models.

I’m used to my long-winded comments killing discussion, so this is both surprising and gratifying. In response to steven first, then deelish:

If I remember C-Span Congressional testimony correctly, the CIA used waterboarding, the sine qua non of enhanced interrogation techniques, on three detainees. In each case, they were people whom the CIA had reason to believe had information about ongoing planning and preparation for terrorist attacks. The three were Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, Abu Zubaydah, and the one I always forget, AKA, “That Other Guy.” According to that same testimony, and this is a finer point, so my memory really shouldn’t be trusted, interrogators did learn details of terrorist plots through waterboarding these three men that enabled the U.S. government to prevent the attacks. This is always “in combination with other information,” however, and any information learned in interrogation is only a lead one has to run down to see if it’s true or not.

Jones linked to an alterweb story by Alfred McCoy that elucidates a lot of the good arguments against coercion. Empathetic interrogation techniques are historically far more effective, almost without question. The counter-argument, however, is that coercion gets an answer more quickly. McCoy correctly points out that this isn’t always true, either. Having praised the article, I feel compelled to point out that I question the accuracy of McCoy’s scale for both the Phoenix Program in Vietnam and the torture in the Battle of Algiers. I haven’t done the research to prove he’s wrong yet, but those numbers don’t seem right.

Anyway, I’m far afield from the question, which was whether ticking time bomb scenarios occur. Every time a police officer comes up to the door of a house, hears terrified screaming inside, and snap-kicks the door open without a warrant, he’s deviating standard procedure in response to a ticking time bomb. There are rules in place that allow such a deviation. Whenever the security provider knows something that’s probably dangerous is happening, but he doesn’t know enough to stop it, that’s a ticking time bomb. I think, for people involved in preventing terrorist attacks, that’s fairly common. Having a detainee that may hold the answers you seek is much rarer, but according to the testimony, it’s happened. Should we have rules in place that allow us to deviate from standard procedure in a ticking time bomb situation? Almost certainly, and we probably do. Should they include physical coercion of detainees, whether we call it torture or not? That’s a separate question that involves as many thorny pragmatic issues as it does moral ones.

Deelish, the author of the New Testament book of Hebrews explained Abraham’s reasoning in Hebrews 11. this chapter is often referred to as the hall of fame of faith, as the author lists case after case from the Old Testament of miracles and great feats of achievement or endurance, all enabled by the faith of heroes. In verses 17-19, “By faith Abraham, when God tested him, offered Isaac as a sacrifice. He who had received the promises was about to sacrifice his one and only son, even though God had said to him, ‘It is through Isaac that your offspring will be reckoned.’ Abraham reasoned that God could raise from the dead, and figuratively speaking, he did receive Isaac back from the dead.” That may not make you any confident about the decisions made by people of faith, but it certainly makes Abraham’s actions more understandable. It also shows how reason and faith can work together to lead to a conclusion.

I think faith, whether in God or human beings, very often looks like this: “I know I don’t have all the information, and I’m concerned that this is not the right course of action, but I’m going to trust the person telling me or advising me to do it.” We do this with doctors, bosses, investment counselors, horse race tipsters, air traffic controllers, and a lot of other people. Whether this leads to unexpected success or catastrophic failure depends on whom one has placed his faith in.

One more, deelish: “In a totalitarian regime a little hypocrisy and corruption can be a humanizing mercy.” Humanizing mercy that offers a way out of totalitarian judgment (at great cost to the totalitarian) is what Christianity is offering, even if Noah is not. It was demonstrated when Jesus said, “Let he who is without sin, cast the first stone,” and again at the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ, to name just a few examples in the gospel accounts. I wouldn’t call those events hypocrisy and corruption, and I’m not implying you would even if you accepted their historicity. But a stern legalist might call them that, and stern legalists of the day did exactly that.

In general, I agree with your statement, though. One of the flaws in non-divine totalitarian regimes is that humans are the ones who execute them. Their moral nature — both weaknesses and strengths — frequently lead them to violate the intent of the state, and this is a good thing (e.g., Oskar Schindler, the North Korean border guard that takes a bribe to let you escape into China, etc.).

One more self-indulgent response to deelish:

The truth is…I am the Hooded Utilitarian.