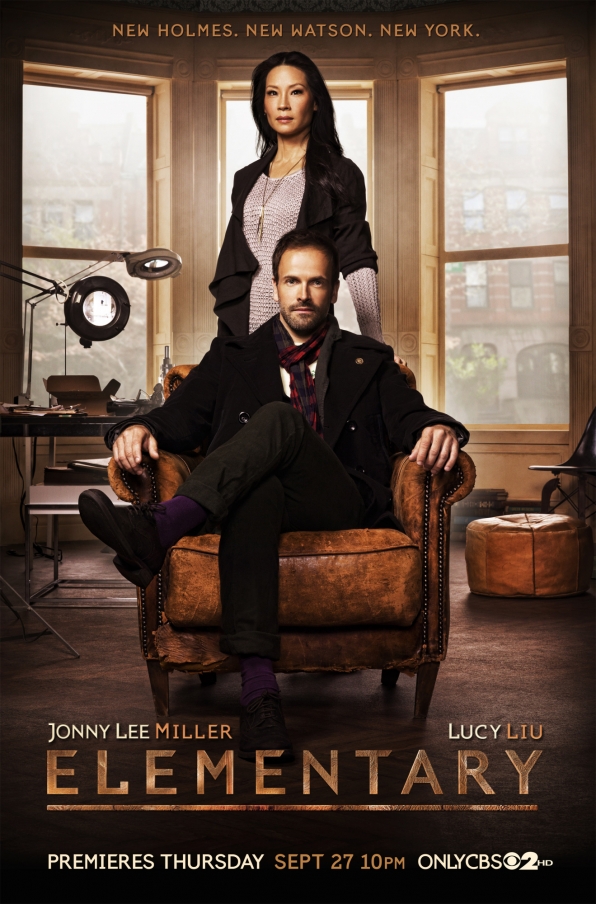

The setup is simple and straightforward. Sherlock is a recovering addict, Watson is his live-in sobriety coach, and together they fight crime.

Sherlock consults for a police captain at the New York Police Department. The captain is played as a solid, thoughtful cop who is both ethical and smart. The captain’s semi-assistant is a detective who, while also smart, finds Sherlock irritating at first (mostly because Sherlock is, in fact, irritating).

In this show, Sherlock is a know-it-all asshole, but not actually sociopathic. He treats people in general rather poorly in regards to social mores but he’s not cruel and he has quite a lot of hidden caring. He searches for justice in part because he doesn’t like seeing people hurt. As time passes in the show, he begins to care (in his own way) for Watson and to push her to re-engage with the medical practice she left behind.

Watson, for her part, begins as a competent but distant surgeon who has now become a sobriety coach. She’s shown as very honorable and deeply ethical. She won’t discuss patients unless she believes their lives are at risk, she thinks of others’ well-being over her own, and she is shown again and again as sensible and competent. The disgrace that caused her to stop practicing medicine is revealed, over the episodes that I watched, to be a mistake not of hubris or competency or what-have-you, but just….a mistake, as all humans are prone to make sometimes. She feels deep remorse over the mistake, as all ethical people would, and she makes penance as best she can.

I’ve read criticism of Watson, as her character, as showing her as fallible, as various things.

But I quite like her, and I think the show portrays her quite well. I’ve met many medicos in my day. Very few admit to human fallibility beyond it being a theoretical possibility that happens only to other people. It takes the very best, the most compassionate, to admit they can screw up. And only by admitting the possibility for those mistakes can such mistakes be prevented. This is dealt with in one episode quite well.

Sherlock himself is brash, snotty, sarcastic, and difficult. But since he always came off that way in the books, I don’t mind.

The reader may be wondering why bother with a new version of this show. The BBC’s latest offering seems to be the current favorite. I can understand the appeal. I watched the first season. The production values are lovely, the acting good, the mysteries competent, but I found the characters less enjoyable than some friends of mine. Interesting enough, but… Maybe I’m too much of a genre hack, but I find sociopath heroes more unlikeable and boring than enjoyable. (For those who don’t know, the BBC Sherlock is portrayed that way.) I enjoy the BBC version for what it is, clever and witty with plot twists.

Elementary is much more like a cozy wrapped up in a police procedural.

The cozy genre isn’t just about the mystery of the week, it’s about the characters who grow over many books or seasons. The tiny choices in life that affect great outcomes.

In that way, Elementary is very much a cozy. Watson, in this verse, is a sober companion to Sherlock’s addict, emotional mentor to a emotionally hurt person healing from addiction, but she also gains from him. Sherlock here is smart. He knows he’s smart. But that intelligence also causes him trouble. He craves connection, and with Watson, he finds it. But finding that connection isn’t enough for him. Rather than just take, he starts to offer things to her.

Being Sherlock Holmes, however, his idea of gifts of friendship are sometimes a little off. He brings her a coffeecup full of spaghetti, since the taste of the food is not impacted by utensils and cutlery. Obviously.

One of my favorite parts of the series occurs when Sherlock goes to a dinner party with Watson’s family. She is terrified that he will make a variety of social gaffes. Instead, he spends his evening subtly convincing her family that she is making a difference in her profession. Sherlock doesn’t even approve of her being a sober companion, but he knows that her family’s approval is very important to her. He does it for her.

Through each of the episodes, Sherlock and Watson solve various crimes. At first, she assists with medical knowledge, forensics, coroner-type information, and what might be called empathic emotional understanding. This ends up surprising Sherlock in the early stages, but as time passes, he relies on her more and more.

Their initial partnership, sober companion and addict, has a time-limit. As their friendship grows, Sherlock eventually convinces Watson to become his mentee in the art of detection.

But the two of them are wonderfully complicated and multi-layered. When Sherlock sends Watson off on her own case, for practice, he tackles what should be the harder case. I was amused and delighted to discover that the show brings much of the pilot episode’s visual imagery back for Watson’s first case, switching their positions.

Eventually, they both decide they do their best work together.

I know HU gets a rep for hating haters who hate, but you know, I just enjoy this show. Both characters are beautifully acted, the mysteries are interesting, the supporting cast is great, and the emotional arcs believable.

I’m sure that means it’s DOOMED. DOOMED to be cancelled.

But hey, in the meantime, the first season is available for sale at the usual Amazon/iTunes/etc.