In a comment to my post from last week, R. Maheras wrote:

“I was at SPX today, and almost every complaint about homogenized superhero comics can probably be made about contemporary small press.

There’s a relative sameness pervading contemporary small press that I don’t remember seeing during the small press explosion of the 1980s.

Zombies, cutesy creatures/monsters, or reality-based angst comics seemed to be bulk of what’s available these days.

In the 1980s, I was snapping up dozens of small press comics every month. At SPX, While I spent about $120, I was hard-pressed to find stuff I wanted to sample. One of the more interesting things I found was actually what creator Pat Barrett himself only half-jokingly labeled a screed: “How to Make Comics the Whiner’s Way.” I thought it was actually a pretty good indictment of what appears to be a substantial faction of today’s small-pressers.”

I was also at SPX this weekend. This comment made me want to use my words and Noah was kind enough to put this up as a separate post instead of hiding it in the comments.

I’ve been going to SPX since 2002 – a few years covering the show for a small local magazine here in the DC area, then one year as a volunteer, and this was my sixth year selling my own comics as the man in the purple suit. (Full disclosure: I also maintain the SPX Good Eats Google Map.)

Over the course of the past decade, my wife and I have come up with a game at SPX. She goes off and finds stuff and I go off and find stuff. When we compare our finds, we ask each other “where did you get that?” It’s very obvious that what she finds interesting in comics is very different than what I find interesting in comics and we always spot very different things at the show, so much so that it’s almost like we’re at completely different shows. I tend to regard that as a feature, not a bug.

My wife picked up Pat Barrett’s book for me and she talked to him about it. He told her that it was written in response to people who knew they wanted to make comics but didn’t know what they wanted to create. Mind you, that’s hearsay so it’s impossible to say exactly what his intention was (and I argue that we should look at the primary source instead of the author’s intent anyway). Having read the book last night, I saw a very pointed sendup of “How-To” books, especially those that are aimed at teaching people how to draw. And yes, there was a lot snark aimed at autobiographical comics, which were all the vogue a few years ago.

One of the interesting things about comics these days is the conventional wisdom that if a comic isn’t about superheroes then it’s pretty much automatically not commercially viable. And that lack of concern about whether or not a book is going to sell has opened the floodgates to allow just about every kind of comic under the sun – both in terms of subject matter available, art style and format. And, as far as I’m concerned, the best thing about indie comics is the almost complete lack of homogenization or sameness on offer.

For example, on my row of tables (I was on what Rafer Roberts called “the fifty yard line” of the room) there were Warren Craghead and Simon Moreton’s minimalist comics, a gay porn space opera, my eclectic collection of books, video game inspired books, and a guy selling bad caricatures and an apology for a dollar. There was also a wide range of books available from the DC Conspiracy, Interrobang Studios, Nix Comics and the Spider Forest Webcomics Collective.

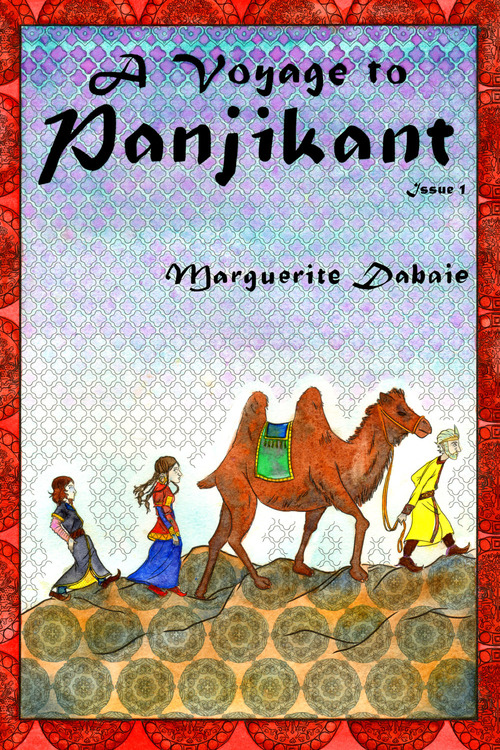

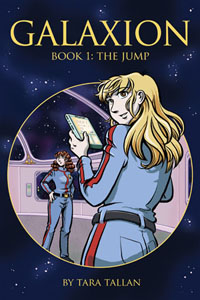

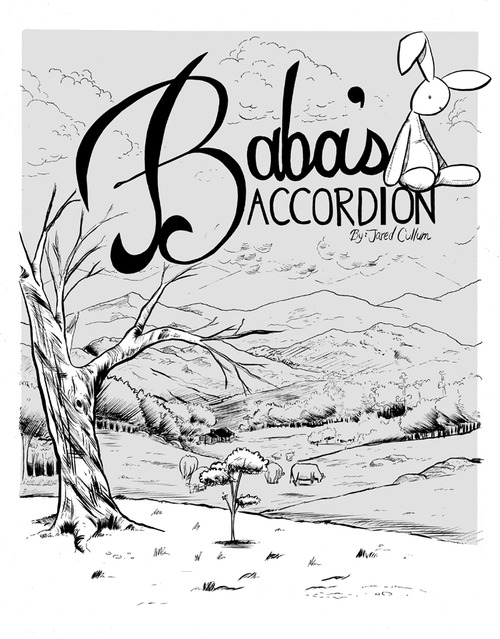

My must-buy book of the show this year was my friend Marguerite Debaie’s A Voyage to Panjikant, a meticulously researched historical fiction about traders living on the Silk Road in the Seventh Century. It’s a beautiful book that’s colored entirely in watercolor. I also picked up a space opera comic called Galaxion by Tara Tallan, simply because it looked interesting. I even went out of my way to pick up the few books from Frank Santoro’s Comics Workbook competition that were at the show – Jared Cullum’s Baba’s Accordion, Alexey Sokolin’s Freefall, and Alexander Rothman’s Vespers.

Not a one of these are “[z]ombies, cutesy creatures/monsters, or reality-based angst comics,” but it’s easy to understand why it seems like that’s what the room had to offer. With such a large variety of material to choose from, it was impossible for any single individual to wrap their arms around everything that was available. I think a certain amount of confirmation bias does tend to creep into what people tend to see at shows like this when the options are so overwhelming. We see what we expect to see because there is no way to really carefully evaluate everything.

I saw volumes of Shakespeare that contained beautiful handcut paper illustrations. I saw a comic printed on a strip of canvas. I saw comics that were printed at mini comic size, traditional comics size, magazine size, square format, horizontal format, and were massively oversized. I saw comics that were photocopied and hand-stapled. I saw mass-printed books with beautiful production values. I saw parody books that were waiting patiently for cease-and-desist letters and wonderful original concepts.

And yes, I did see some zombie books because zombies are big in pop culture right now. I saw autobiographical comics because most first novels are bildungsromans and it shouldn’t surprise anyone that comics follow the same patterns as novels. And there is always a great deal of cutesy stuff on display because the one thing that always sells at a show of such magnitude is a quick, easy hook that makes you laugh and only costs a few bucks.

And yes, you could make some of the same complaints about the books available at SPX that can be made about superhero comics – some are poorly drawn, some are poorly written and some are not well thought out at all.

But you cannot complain that indie comics have crippling continuity issues that prevent newcomers from picking them up. You cannot complain that indie comics present a straight white male view of the world that is not friendly to women and minorities (in fact, there was a greater preponderance of books with the word “feminist” in the title this year than there has been in years past). You cannot complain that indie comics are dominated by white males (the creator split was about 50/50 gender-wise, not so much racially). You cannot complain that indie comics are mired in endless editor-driven events that force you to buy a dozen books to get the full story. You cannot complain that indie comics have devolved into corporate IP farms whose stewards are more interested in maintaining the long-term viability of characters than they are in character development.

The real joy of attending a show like SPX is that everyone in the room is there because they want to be – because they are desperately, passionately in love with the medium and the possibilities inherent in comics. And yes, the creators would really like to make money. But most of them know that they will probably not break even, but for some weird reason they show up anyway.

Given that half of the people exhibiting at SPX this year were there for their first time, it’s entirely possible that a good portion of them went for the easy options and chose the same basic topics that most newbies choose. But if that’s all you saw then you were not looking very hard because there was a lot of weird, crazy, interesting, creative, exciting stuff available. I had to stop browsing because I went over budget twice – and I intentionally avoided the big publisher tables. I’d even go so far as to say that there was a book in the room for just about anyone from any walk of life. And that’s absolutely not something that you can say about mainstream superhero comics.

I agree that there was a ton of variety at the show. 98% of that variety held no interest to me at all, but I definitely saw a lot of comics and art in varying styles, formats, genres, and skill levels. It was perhaps a little too much stuff though.

I think the question of whether there was too much stuff is a worthwhile discussion. It’s a careful balance between providing an open marketplace and overwhelming potential customers.

BTW Derik, did you see that one of your favorite books from the Comicsworkbook competition – Freefall – was there? I completely forgot about pointing it out to you, even though I was standing right next to you.

Derik, I really feel that’s what will ultimately keep the comic industry afloat. If you walk into a bookstore, probably 98% of the books on sale won’t interest you (or anyone). It’s embracing variety that will keep non-traditional “comics” people coming in and guessing.

Though, it’s true that the show was overwhelming for me, also. My hope is that the genre will have enough variations to justify specialized marketing and shows, and that isn’t just left to manga and superhero comics. Or, better yet, comics are more folded into the literary market, since that’s already established.

Great piece RM. I’ve been trying to formulate my thoughts for the upcoming roundtable here on ‘indies-in-context,’ and my mind keeps drifting back to SPX, which I attended two years ago. My memory agrees with you completely– there always is a lot of variety, whether at SPX, APE, MoCCA– even though I emotionally agree with the complaint that independent comics are a lot of the same old thing, over and over again.

I think this has a little to do with Derik’s point– I often feel ambivalent walking around the shows, and don’t feel drawn to many works. But I think there still is a homogeneity, not on the level of content, but on a more structural level. I feel like I see the same shorthands over and over again for humor, for characterization, for the passing of time, scattered across humor comics, gross-out battle comics, slice of life comics… Comics are pretty concerned with nostalgia, but I wonder if that comes packaged with a preoccupation with tropes. Or if comics are just so incredibly time consuming and laborious, it becomes an art-form of shortcuts for most.

“And yes, there was a lot snark aimed at autobiographical comics, which were all the vogue a few years ago.”

More like since time immemorial as far as indy comics are concerned. And that includes the accompanying snark.

“One of the interesting things about comics these days is the conventional wisdom that if a comic isn’t about superheroes then it’s pretty much automatically not commercially viable.”

Not that this has anything to do with SPX but I’ve been made to understand that the real star of recent years has been Image – and not so much with superhero books. I’ve heard that Brian K Vaughn is making more money on Saga than he has on any of his previous comics projects. Greg Rucka is doing ok as are the people behind Manhattan Projects. Image projects have even rekindled the investor boom/bust of the early 90s. Don’t know if Prophet provides a decent living for its artists with its small print runs but the early issues of the new series were quite imaginative (if rife with homage).I think this is the more good “crap” future Kim Thompson once called for.

This isn’t the small press but it’s the sustainable future some of those guys might want to aim for given time and talent.

Hey there RM, just FYI, Mr. Santoro pointed me towards some the comics you did for him a while back. I asked him about making comics without really being able to draw. he graciously relayed his story of teaching you and linked me to your work for him. It really gave me hope that it is possible for me to do this, so thanks.

SPX and small press in particular is facisinating simply because it’s so diverse. Like it seems there are sub-groups that operate independently but all have different niches and aesthetics, there is overlap but not to the extent I would think.

Like I’ll be honest….I’m a bit into Boy’s Comics like Josh Bayer or Pat Aulisio, but I’ve come to see that their is a definite backlash against those “type” of comics from some of the small press community. But at the same time, I really like Simon Hanselmann or a JMKE…so it gets weird for me when those sides quarrel.

The selection of material at SPX sounds like a problem directly related to so many people being there. When you look at small press stuff online, the cream rises to the top most times. At least for me.

Just to reply to the Prophet comment above…

Prophet is a bit different. It probably SHOULD have got cancelled issues ago due to sales but I think the acclaim has kept it around. It’s work for hire so I doubt they’re making much off of it, maybe I’m wrong though.

My problem with the current IMAGE and creator owned buzz books (and this is a very common perspective) is that many now seem like half-assed, mediocre, movie/tv show-bait. It seems like these writers all suddenly figured out “I can just turn my unsold screenplay into a comic. Sweet.”

Image is an interesting conversation. I’m a little cynical about great serialized works, just because I’d like to see more stand alone works of greater quality. The reliance on serialization isn’t unique, other trends seem to be going that way, (golden age of television,) but it reminds me of a piece of Noah’s last year that comics is, kind of sort of, understood through genre, through character, before it is understood formally. These books also can be the most annoying perpetrators of the unfeeling quip-iness and empty bad-assery that then crops up on the level of minis, webcomics, less direct to cinema work.

I have a draft article in my head about whether or not the default state of comics is serialization. It’s certainly a good business plan for any number of reasons, but I’m not sure that they necessarily have to be because of the medium or if people just tend to gravitate in that direction because “that’s the way that people usually do it.”

The thing about serialization is once you get a hit, like with Fables, Batman, or The Walking Dead, you just keep pumping out more product, forever. It’s the closest thing to risk free easy money in comics.

When I’m feeling most generous about serialization, I figure that its necessary in order to establish complex characters in comics, as it takes both time and a lot of physical pages to convey anything. But I don’t really believe this…

I think people conflate the kind of pleasure they recieve from serialization with the pleasure of buying and reading a comic. (I’m not even talking about weekly floppies, but trade paperback volumes.) I also think that the industry is built around characters, And its easier to add onto this framework than expect to develop a separate one for standalone works. Which may tie in why some publishers have to market independent works as auteuristic visions– celebrity authors can be fitted into the same framework as batman.

At this point I would think they’re simply serialized so they can be sold two ways. They’re clearly designed for collections, I rarely see a reason for there being individual issues especially since most are quite long stories (if they make it past 6-12 issues).

Ah if we are not simply speaking about floppies….yeah, I think now the mindset is that if your comic is successful at all, you must turn it into a continuing feature. It’s definitely a question to ponder but yeah, I think it may boil down to “that’s how it’s always been done here” in most cases.

“Which may tie in why some publishers have to market independent works as auteuristic visions– celebrity authors can be fitted into the same framework as batman.”

I just wanted to quote that, because it’s so true.

At SPX, I made a point of walking through and looking at every table, but I’ll admit my bias against art I don’t like can sometimes steer me away from a well-written book. But in all fairness, my art filtering bias is no different for mainstream comics, so the level of the playing field is exactly the same.

I think what I’m getting at is I believe the variety of material available at this (my first) SPX was not as broad as I had anticipated, and because of that, I was somewhat disappointed. It doesn’t mean I won’t be going in the future, but simply that next time I’ll have lowered expectations.

I really wish someone would publish a comprehensive book about the small press boom of the 1980s (not the b+w independent comic book boom, mind you — although I don’t see why some, or all, of those could be included).

It was pretty remarkable, and the variety was pretty amazing. I have several thousand small press comics from that era, and I never get of tired going through them again and again.

And no, the 1980s was not my early teen years that I’m simply wrapped up with nostalgia about. For me, those years were primarily in the 1960s.

The fact is, I think there was something about the 1980s self-publishing boom that was special, and hopefully, someone will sit down one of these days and capture it in a big coffee-table book.

From an economic standpoint, serialization is a no-brainer. The default, out-of-the-box solution for a comic book shop in the English-speaking world involves setting up as many regular Wednesday pull lists as you possibly can as quickly as you can. Regulars are the heart and soul of any retail business.

But if you remove the economics from the decision-making process – pure art comics made by someone who is honestly not looking to make a living from the production of the comics – is serialization always going to be the default setting? Like I said, I’m still assembling my facts because I just don’t know.

R – I’ve been making a deliberate effort to look at every table every time I go to SPX and my wife still manages to find stuff that I never would have seen. I think a large portion of that has to do with the fact that we’re looking for different stuff so our eyes are drawn in different directions. It’s a feature, not a bug.

I would venture to say that the indie comics boom as exemplified by SPX doesn’t bear a lot of relation to the indie comics boom of the 1980s. For one, the one in the 1980s was pretty much limited to the existing distribution methods, so everything had to have the same general shape – either magazine-sized or comic book sized. Otherwise it wouldn’t slot into the supply chain.

These days the distribution methods are so diffuse that pretty much anything goes. And if you’re used to looking at mainstream commercial comics on a regular basis, walking into a room where mini-comics are the default format can be quite a shock.

And because you’re used to looking for a certain format, it can be very easy to filter what you parse as “comics” into a more manageable subset. (I speak from experience.) So you don’t sound condescending next time, perhaps you could shift your expectations instead of lowering them.

My experience is that serialization isn’t the absolute norm with minis– although its prevalent enough, and is definitely the norm with webcomics (which expect the least amount of financial compensation.) My frustration with minis come from the fact that a lot of independent comics have a kind of glib, self-congratulatory nature that I always assume (maybe wrongly) comes from serialization itself. Which is probably beside the point of a conversation on serialization, but links back to what people day about the monotony about comics content. It’s not that there aren’t enough indie, mini, standalone comics, or that they aren’t varied enough in content, but that they consistently rely on the same storytelling shortcuts that make mainstream comics grotesque to me.

The point about comics relying on the same storytelling shortcuts is very valid. A point that was made on Derik’s minimalism panel on Sunday afternoon was that when directors were making films in the teens and twenties, there was not a lot of baggage about “you have to make films in this way.” They got to invent a lot of stuff because there was no established tradition – this was both a good thing and a bad thing, for various reasons.

For me, one of the appeals of BD is that it’s an entire comics tradition that I have no insight into and it follows that most of the English-speaking tradition doesn’t either; looking at stuff that nobody else is even aware of provides a different perspective on what everyone else is looking at. I suspect that manga provides the same fresh perspective.

As far as I’m concerned, the most interesting stuff on the floor at SPX is the material that makes an attempt to provide a fresh approach to making comics. My wife likes things like the scroll – stuff that challenges what shape a comic can be. I like stuff that pushes at the edges of what the art in a comic can look like.

It’s down to personal taste, really. But you need a show as big as SPX to allow some of these weird hothouse experiments to come together. It’s a power of numbers thing.

RM– the point about the different formats is a great one. I think what it does, in addition to pushing the boundaries of a comics definition and etc, it also changes the way we understand collecting, which is really bound up in comics reading. It makes it more of an active collecting, an assembling of a wunderkammer, than a market, auction driven obsession over mint condition, hundreds of identical boxes and baggies… I’m contradicting myself a little bit, as last year I came down really hard on Building Stories, and the reinforcement of the idea that reading comics is a sometimes novelty via creating novelty formats. I think there’s still danger in that, but novelty formats can be thoughtful, and maybe can even establish themselves as new traditions, with new storytelling techniques to be turned into shortcuts, maybe…

One of the most important things a tradition can do is identify the default assumptions that have set in, because default implies that there are settings that can be changed. You’d think that hand-stapled photocopies would be an outlier, but in a context where supply costs tend to eat up the majority of the budget they thrive.

At a very basic level, providing a limited environment where something like relative production value can be balanced against cost per book by any number of people with a wide variety of results is very valuable.

And forcing comics readers to buy their storage at the Container Store because the LCS doesn’t have boxes for mini-comics really does force a new take on collecting. These books are not collectible in the mainstream comics sense – they are mementos of a specific time and place that only shows up once a year. A comics Brigadoon, if you will.

I think you’re right about novelty. It is very easy to take the slippery slope towards kitsch. But it’s also worth noting that novel means new.

RM– Touche! Novel does mean new. This is a very thoughtful look at minicomics, and I like how its tempering my own thinking… great prep for the roundtable too.

RM — indy comics were only marginally related to the small press comics from the 1980s I am referring to. Many indy comics can still be found in discount comics boxes at cons and stores, but the small press press material is rarely seen — except perhaps on eBay. Most small press titles back then had print runs of 50-200, so unless you were around buying stuff back then, you’ve probably only seen the tip of the iceberg.

You may not realize it, but you addressed what I think the problem is: many creators at SPX are trying to be little businesses, and are thus trying to appeal to a wider audience than the self-publishers of the 1980s. Back then, the spontaneous nature of the movement, which popped up because of the sudden and widespread availability of relatively inexpensive copy machines, was much more stream-of-consciousness creativity. That resulted in a wide, free-for-all freshness in creativity that I did not see in abundance at SPX.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Gilbert Hernandez wins PEN Center USA award | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

R – I think my issue with your assessment of SPX is that I can’t wrap my head around what your expectations were. Every time you say things like “free-for-all freshness in creativitity,” I can’t help but be struck that you and I approach that phrase completely differently. As far as I’m concerned, there was a massive freshness of creativity and a very stream-of-consciousness approach to what was available.

And I can’t help but wonder what you think indie creators of the 80s were intending with their small print run comics if not trying to run small businesses. Certainly many of them were just fucking around in the zine mentality, but if they laid out the money to print that many comics and demanded money for them, there was a business aspect to the approach – even if you didn’t see it. And that may be because there were no marketplaces like SPX at the time.

Tell you what – next year, come find me at SPX (I’ll be the guy in the purple suit) and we’ll walk around the show looking at comics and you can point out exactly what you’re talking about and I can point out exactly what I’m talking about and maybe we can come to some kind of synthesis on this because right now we’re very clearly talking past each other.

@ R. Maheras – can you give examples of the variety in 80s independent comics? I grew up during this time as a mainstream fan who was also really into the Mirage TMNT, Cerebus and a little Concrete. As a cartoonist who doesn’t fit into the contemporary mold (I’m 40 and draw a left-of-center scifi/fantasy boy’s adventure story), I’m constantly frustrated trying to find the audience for what I’m doing. I tabled at SPX back in 2002, and I wonder if it would be worth the time and expense to bring what I do now to Bethesda.

N – I took a look at your site and I think it would absolutely fit in with what I saw at SPX.

Also note that I’ll be forty next month and don’t fit into any sort of contemporary mold.

RM — In the 1980s, most self-publishers were doing what amounted to art for art’s sake. At SPX, a large portion of creators seemed to approach their creative endeavors from a commercial standpoint — just like the bigger mainstream companies. For the majority of small-pressers back in the 1980s, making a profit was rarely even on their radar.

Two things strike me as amusing about this characterization.

First, most creators at SPX hope they’ll make money while knowing full well that they probably won’t. I’ll grant you that some creators make a stab at making commercially viable books, but that varies greatly from creator to creator and sometimes from book to book. I wouldn’t, however, compare many people in the room to mainstream companies.

Second, I’d be willing to bet that small press creators in the 1980s were also hoping that they’d make money but were resigned to the fact that they probably wouldn’t (just like today’s creators). This is the natural condition of most creators working in the non-commercial fringes, regardless of medium.

The only real difference between the 1980s and the current crop of creators with regard to commercial asperations is that (again) the distribution methodology has opened up and it’s easier to find tips and pointers about how to orient yourself properly. I maintain that if these resources had been available in the 1980s, your idealized age would have looked very differently.

Also, I don’t think that there is necessarily any mutual exclusivity between aspirations towards profit and art for art’s sake. It was a room full of people trying to sell the art that they made because they wanted to make art.

RM–we’ll just have to agree to disagree then. There is no idealization on my part, because I started my self-publishing in the early 1970s, and that era was quite different than 1980s self-publishing, which I stumbled upon quite accidentally in 1985. I also own hundreds of fanzines from the 1960s, and that decade is also quite different. The 1990s was a continuation of the 1980s, but slicker and less innovative. By the 2000s, there was an entirely new crop of self-publishers who had little or no knowledge about what had come before. It wasn’t better or worse — just different.

Amen to that, Russ…I, too, self-published in the early ’70s, and I confirm your take.

Nfpendleton — Stuff like TMNT, which had print runs in the thousands and were distributed via the direct market, was more “mainstream independent” than the self-published comics I’m talking about. They were generally printed, collated and stapled by hand, and almost all were distributed via the US mail.

As for whether or not SPX would be worth setting up a table at, I guess it depends. I might do it pne of these days, but that’s only because I now live in the DC area and outside of the table cost, my expenses would be minimal. If I had to travel from hundreds or a thousand or more miles away, there’s no way I’d do it.

“In the 1980s, most self-publishers were doing what amounted to art for art’s sake.”

Please give us examples, not only of the art for art’s sake stuff but also the better independents. Otherwise, it’s impossible for me to understand the comparison to now.

Russ, are you talking about the stuff the Journal used to review under the catch-all term of “New Wave comix” and/or the type of comics covered in Jay Kennedy’s “The Underground And New Wave Comix Price Guide” from 1981 that weren’t necessarily classic underground comix of the Zap! et al school but weren’t quite fanzines either?

Some specific examples would really be useful. Otherwise it just sounds like Barry from Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity: “You wouldn’t be familiar with our immediate influences…they’re mostly German.”

I like that 2 examples of originality at this year’s SPX were Video Game Inspired and Shakespeare Adaptation. (Also, I’m glad to be part of this conversation. I think it’s an important one. So, thank you for mentioning my little joke book.)

You’re welcome, Pat! I really liked your book.

I was using both books as an example of the diversity of genre, not necessarily originality. Although the Shakespeare paper cutouts were really extensive and I’d never seen anything like that before.

Daniel — Yes, stuff that TCJ called new wave were definitely part of the mix. But TCJ barely scratched the surface with their coverage.

Because there was no other way to distribute small press material except the US Mail, catalog zines sprung up with listings. Clay Geerdes published one, as did Kevin Collier. But, as I recall, when Collier stopped publishing his catalog for personal reasons, Tim Corrigan stepped in and began publishing a monthly catalog “Small Press Comics Explosion.” It soon became THE go-to catalog source for all of this new material, and soon there were hundreds of small press publications being listed inside every month.

I understand the frustration about small press examples, and I’d love to grab a few dozen and post links. But the problem is, I don’t have access to my collection at the moment. The earliest I can access my stuff and grab a stack of examples is in October, but that won’t be helpful now. THAT’S why I wish there was a comprehensive book out there about the movement.

What I can do right now though is post these links to a handful of cover scans I did a few years back for some thread discussion. But again, this is but a tiny, tiny drop in the bucket.

http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/oldzines-01.jpg

http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/oldzines-02.jpg

http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/oldzines-03.jpg

http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/oldzines-04.jpg

http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/oldzines-05.jpg

A while back Fantagraphics published a small-sized reprint anthology titled “Newave!The Underground Mini Comics of the 1980s,” but while they did highlight a few key publications, the focus was incredibly narrow, and, from my vantage point at least, it was little more than a cursory primer and in no way captured what was really going on in the small press movement of the 1980s.

As some of you may have noticed, a few of the titles above later morphed into slicker black-and-white independent comics that were professionally printed, had much higher print runs, and were distributed via the Direct Market. But the earlier small press versions are virtually unknown, except to the original creators and a handful of small press collectors.

Sure, I see Ralph Snart, some Matt Feazell stuff and Ultra Klutz. Of course the Zot! mini has an Eclipse logo due to their involvement. I have one of those somewhere, and that really needs to be considered as a special case.

I have a few boxes of minicomics from that era myself, including some early stuff that would probably be labeled “furry” these days. I seem to recall that there were a lot of those, though probably fewer than I remember.

I remember Crumb in some interview or other talking about micro-run ‘zines from an even earlier pre-copyshop era that one could mail away for, with his and brother Charles’ ‘zine “Foo” being just one example. Some might call this all ‘zine culture, and that seems fair.

Yeah, I actually exchanged a number of letters with Clay Geerdes back in the 1980s trying to get his read on classifying the various small press stuff being published.

The overlap between various self-publiahing factions from that era is simply too great to split things up and ignore the rest, as Fantagraphics tried to do with their “Newave” book. Not only did it give a wildly distorted view of what was actually happening back then, it didn’t even do a good job covering the stuff it had pigeon-holed as newave. For example, their Steve Willis and Brad Foster examples barely scratched the surface of what those two had done, yet there was no real indication of that to an uninitiated person reading about 1980s newave material for the first time.

Unfortunately, Russ, the examples you provided don’t really support your thesis that the indie comics from the 80s were not about profit. To my eyes, the covers are all clearly aping more mainstream sensibilities and many of them have price tags clearly visible – an obvious sign that profit was at least part of the consideration. And you undermine your argument further by pointing out that there were catalogs available – creating your own supply chain is usually a good sign of a profit motive somewhere in the mix.

And I still don’t see the difference between those examples and something like Baba’s Accordian (above), which is printed on 8.5 x 11 paper, folded in half and stapled. The newer book has a cardstock cover and has better print quality, which is pretty much what you’d expect from three decades of advances in print technology. In this photo I can see at least a dozen books that fit that description.

I honestly wonder if the small press guys from the 80s would be using photocopiers if they were presented with the wider variety of printing options available today.

At this point, I’m having difficulty reading your argument as anything but “it’s different because I say it is.”

After seeing those covers I’m so glad I missed the small press comics of the 80s.

Oh and because I forgot this thread was here…

RM: Yes, I got a copy of Freefall from Alexander (who I went by to say hi to anyway).

Marguerite: Agree on the variety. My complaint about stuff being uninteresting to me, was just about me. I hate most comics, but I accept that most people have very different tastes than mine. I was actually a bit surprised by the number of comics I did find of interest enough to pick up (though not all of them have turned out to be worth it in the end).

RM — I told you those scans were all I had available, and they were just a tiny representation of what was published back then. The thread I scanned them for had nothing to do with this discussion. It is the equivalent of if I went to SPX last weekend, took a photo of one Fantagraphics table, and argued that the contents of that one table were representative of the contemporary small press movement. I can’t help it that you have no knowledge of self-publishing roots, and seem to believe that it was invented in the past 10 years or so. While I’ve only been self-publishing since 1974, I at least have a working knowledge of self-publishing efforts in the 1930s through my entrance on the scene.

What you perceive as “condescension” and an attack on what you appear to think is exclusively your movement, is, in reality, simply an honest observation by someone who has a far wider perspective about the subject of self-publishing than you.

Baba’s Accordion would have probably fit fine in the 1980s, but much of what I saw at SPX wasn’t in that category.

And your wrong assumption about the handful of 1980s publications that attempted to put together a repository of available publications where people could find the stuff is also a spinoff of your lack of knowledge about past distribution channels available to a self-publisher. As I alluded to, mainstream-oriented publications like “The Comics Journal” and “Comics Buyer’s Guide” pretty much ignored the bulk of small press material that suddenly appeared in the mid-1980s – which was ironic, since both had self-publisher roots, and just a dozen or so years earlier, self-published material was a big part of the comics lovers’ equation.

The emergence of the Direct Market in the late 1970s drastically reduced the number of traditional self-publishers, who generally published comics-related material for fun and love of the medium. TCJ has since shifted its focus dramatically since then, but in 1985, it was a different world. TCJ and other slick comics-related publications focused primarily on mainstream and the then-emerging independent comic book industry. Self-publishers who published just for the hell of it were marginalized, and ways for them to find other self-publishers and people to share their publications with began fading away.

So self-publishers started banding together to create their own distribution network that was independent of the slick comics-related publications distributed through the direct market. This had been done earlier by “Factsheet Five,” a catalog developed for reviewing general fanzines from all areas of popular culture interest, such as music, film, etc. Comics-related fanzines were also occasionally reviewed and listed, but were basically lost in that publication’s fanzine shuffle. So when the comics-related self-publishing boom suddenly burst onto the scene, since there was no Internet, and no reliable access to other self-publishers through the Direct Market or mainstream comics-related publications, self-publishers started gravitating – ala “factsheet Five” – towards the handful of comics-oriented “review ‘zines” that popped up. In effect, they established their own distribution network at the grass roots level — a distribution network that was almost invisible to the average comic book collector.

And whether you realize it or not, their motivations and expectations were largely different than the motivations and expectations I observed at SPX. In fact, I think many of the small press creators from the 1980s would look at a lot of SPX material and lump it into the independent comic book category, not what they would have perceived as true small press.

Again, I’m not saying there were not any small pressers at SPX (there were). What I am saying is there are far fewer of what I would classify as true small pressers there you probably realize.

Russ, as I recall, even at the time, the Journal articles (mostly by Dale “Dada” Luciano, IIRC) made it clear that there was no possible way that they could cover everything out there that qualified for their rather loose definition of “Newave Comics”.

But at the same time I think I can understand and even share (to some extent) your nostalgia for oddball 80s self-published weirdness. There was something genuinely wonderful about that pre-web era of mail order ephemera: not just minicomics, but also things like the early Subgenius mailings, ZONTAR magazine, etc. that weren’t quite comics, but weren’t quite traditional fanzines either. Receiving such publications in the mail (or even just finding them tucked in a comics shop) truly felt like receiving transmissions from some sort of alternate universe.

The fact that there were no blogs or Tumblr pages and certainly no conventions specifically devoted to this sort of thing meant that you had to really seek the stuff out and this perhaps added to its mystery and magic. Even Factsheet 5 or Ivan Stang’s book High Weirdness by Mail could only really scratch the surface.

But let’s face it, Sturgeon’s Law applied then as now. Not everything was as good as Cynicalman!

Daniel — Agreed. At times it was like panning for gold in sewer sludge. But what I found remarkable at the time is that there was far more interesting and well-crafted stuff than I ever expected.

Regarding TCJ’s coverage. My take is that in the 1980s, they never really understood how big and diverse the self-publishing movement had suddenly become, and because of that, they pretty much ignored it. If not for the underground-ish stuff being published, I doubt they would have covered the movement at all. I think that fact was simply reinforced when they published their totally inadequate “Newave” book a few years back.

I thought with their editorial shift during the past 15-20 years from mainstream-independent to independent-avant garde, they would have had a better appreciation for the 1980s stuff. I was obviously wrong.

Here’s a nice little recap of the 1980s small press scene, complete with a decent array of scans.

http://www.davidleeingersoll.com/miscellenia/keeping-sane-with-bob-and-randy-the-hsc-interview/

I think this quote about the 198os small press mindset sums things up pretty good:

“As far as a career path, sure it would have been great to be a comic writer or a publisher and get paid for it, but that was never really our goal. We did it because we enjoyed doing it and being part of that community. We liked the people who were part of that subculture. If something happened more than that, great, but that was never the focus.”

And let me just say to anyone out there… if you don’t know who, say, Daryl and Joe Hutchinson are, then you don’t know shit about small press history.

I don’t know anything about small press history. I don’t really see how that attitude there is different from the way most self-publishers work now, though? It’s a hobby/passion for most folks, not a career path, right?

Like this blog…

Looking at the scans provided I’m not seeing a great deal in the way of aesthetic diversity, or even anything that veers too far from the comic vernacular of the day. That’s not to say I think they’re better or worse than what I see coming out of the small press at the moment, (having not “been there” for the small press boom of the 1980’s I’m not qualified to make the call). It is to say that I think the burden of proof is still upon Russ.

I think Russ would be hard pressed to prove that the motives of the small press artists of the 80s were much different from those of the current era. In any case, it’s a somewhat irrelevant argument since I would be glad if the majority of the artists emerging from the 80s small press scene were “art for money’s sake” cartoonists if only they produced a stream of comics “masterpieces”. You know, like other “art for money’s sake” cartoonists like George Herriman, Charles Schulz, Jack Kirby, and Alan Moore.

As for diversity, it would be interesting to compare the number of female small pressers working during the 80s compared to now. Or Black, Latino, Asian, LGBT etc.

Perhaps a more salient question would be to ask what the 5 best mini-comics to emerge from that era were. Is there some as yet undiscovered treasure which hasn’t been reprinted? Thankfully, the internet and small press conventions like SPX mean that it’s become easier for cartoonists to monetize their hobbies and stay in the business longer.

OK, let me sum it up this way: SPX was far more commercialized than I expected it to be, there was far less grass roots variety and experimentation than I expected there to be, and because so much of the material was professionally published in a graphic novel-type format, the prices, over all, were far higher than I expected them to be.

I’ll be damned if I’m going to drop $8-$30 simply to SAMPLE something I’ve never seen before.

And since I haven’t addressed the price aspect – except indirectly, in the form of my observations about professional printing – let’s go there.

In 1988, the average cost for photocopying was 10 cents a side. Thus, the average small-sized 8-page minicomic (an 8 1/2 x 11 sheet of paper folder into quarters and trimmed) could be printed for 20 cents. A 16-page minicomic could be printed for 40 cents, a 24-pager for 60 cents, a 32-pager for 80 cents, etc.

Your typical digest-sized minicomic (an 8 1/2 x 11 sheet of paper folder in half) was exactly double the cost of its smaller counterpart to produce. For example, an eight-pager (two sheets of paper printed on both sides and folded in half) cost 40 cents to print, a 16-pager cost 80 cents, a 24-pager cost $1.20, a 32-pager cost $1.60, etc.

Printed color covers were rare back then because color copying would usually set you back more than $1 a copy. But because the print runs were frequently so low, many time the minicomics that did sport color covers were hand-colored. That’s right… hand-colored.

Today, 25 years later, a copy at FedEx is 12 cents. Inflation has DOUBLED an item’s cost since 1988, but since copy costs have only gone up a measly 20 percent, it’s actually much cheaper printing your own ‘zine these days than it was 25 years ago! Of course, I already knew this because I’ve belonged to an amateur press alliance (APA) or fanzine co-op, since 1990, and regularly have to print up my mailings or ‘zines. So, what this all means is if tomorrow I walked into FedEx with proofs for a 32-page digest-sized minicomic, I’d walk out paying $1.92 a copy. If I were printing in the smaller format, a 32-page minicomic would set me back 96 cents a copy. Substituting a color cover for either size would cost me an extra 44 cents a copy, so the most my 32-pager would cost is $2.36 or $1.40 – depending on the format size.

At SPX, however, it quickly became apparent that a 32-page digest was going to set me back $6 or even $8 a pop – way too expensive to sample anything except the most professionally drawn stuff, in my opinion. The slick, graphic novel sized books were even worse, and would have set me back anywhere from $8-$20 a pop, on average, with some way more than that.

So knowing what I know about production costs, many of these folks were running little businesses, and expecting me to pay premium prices for material that was either amateur, or a total unknown. I’ve been a dealer at conventions since the early 1970s, so I understand all about costs for tables, transportation, blah, blah, blah. But again, the bottom line is that many of these enterprises are being treated as little businesses, with wholesale to retail markups, and thus the labor of love factor that was prevalent in most 1980s books is either secondary, or not there at all.

Suat — Let me get this straight. You’re arguing for capitalism-motivated art rather than art for art’s sake?

The mind reels. Surely this must be the eve of the Apocalypse!

Russ, you’re conflating two things; price and attitude.

The argument that the prices should be lower is totally reasonable — but it’s a business argument. You’re saying that they’re failing to give you what you want as a consumer.

Suggesting that lower prices has something to do with greater purity is just silliness, IMO. But suggesting that folks might consider trying to sell cheaper to reach out to more customers seems pretty reasonable.

Noah — I totally disagree about price and purity. Many small pressers in the 1980s would simply TRADE their books with other small pressers. SPX wasn’t set up that way and certainly did not have the art-for-art’s-sake vibe. Don’t shoot the messenger here.

SPX may have started out like that, but it sure didn’t seem that way to me now.

That second site of scans made me even gladder I wasn’t around to see the 80s self-published comics. And that Fantagraphics anthologies was similarly pretty awful, I read it (at least the parts I could bear to read), and quickly gave it away.

As for prices at SPX. It’s easy to say “a photocopy costs $.12” and then that the comics are too expensive. But, at least the comics I looked at and/or bought, were rarely of the simple black and white photocopy variety. I got, color books, large books, risograph printed books. The few things I got which WERE simple small black and white print-outs were pretty cheap.

I think it’s a positive sign that comic artists aren’t chaining themselves to the same old cheap black and white formats. Yes, you can do great work with those materials, but there’s plenty of other options out there and not everyone is best suited for that medium/format.

I will also note, that I got a lot of the comics I brought home as trades from other people. I wasn’t even asking for trades. I was just giving out my comic (small, full color, cardstock cover) and people were offering me comics in trade.

Price does seem like a concrete difference between the 80s and now, though, right? Does everyone agree that that is a difference? Because that seems like the first really solid distinction that’s come up.

The fact that there was an active trading policy seems to be another real distinction. But again, that might be a holdover from ‘zine culture of the time. Still, it’s a reasonable point.

Have we started excluding web comics from the small press. Those are “free” or have alternative sources of funding. Why go snail mail when you can reach out to more people via the digital route?

Russ: “Surely this must be the eve of the Apocalypse!”

It surely must be a sign of the Apocalypse when cartoonists are compensated for their efforts. The dumpster diving artist model is obviously the superior one. It’s certainly purer. Because we all know that money inevitably corrupts art, right?

And just in case anyone is wondering, there has been at least one story of a relatively well known alternative cartoonist dumpster diving to get by.

So trying to design your book so it would appeal to a target audience is selling out, Russ?

Also, about Prophet… It’s a superhero book through and through. One with a Heavy Metal aesthetic, but it has Badrock and Diehard in it. It’s a cape comic. I also believe it sells better in trade.

Noah: I think the price difference is an issue of printing/design/format differences. It’s way easier to do short runs of a variety of different formats now, so people can make comics that might be more expensive than a photocopies minicomic. But for people still doing photocopies minicomics, I don’t think prices are that high. Warren Craghead and Simon Moreton were selling their split minicomic for $2. It was a small format photocopied (or maybe inkjet printed) comic. I got a, I think it was $5 or $7 mini from Laurel Lynn Leake, but it’s slightly bigger than digest size, on multiple colors of paper, has two tone riso printing on some pages, one tone on others, and has a full color printed page inside. It’s a really nice, well put together comic that moves slightly into the “art object” arena (at least more so then a straight up photocopied mini or a plain trade paperback). I’d say the price is reasonable for that.

Noah’s point on the increased cost being a business decision, and not one of purity, is very apt. While the price of copying hasn’t inflated, the price of mainstream comics has increased, and I think costs go up to reflect that. Also,t he price of exhibiting at these shows has probably increased dramatically. Also, trading is alive and well– most of the independent comics I’ve collected are from trades.

I sympathize with Derik– Three years ago, I lived in Minnesota, and I worked my ass off to get Jacob and my collective, The Carleton Graphic, to table at MoCCA. I now live 10 minutes away from the event, and couldn’t bear to go this year. I probably won’t go next year either.

Yeah; I wasn’t saying that the prices were necessarily unreasonable, just different. Reflecting the way in which the market has moved from comics hobbyists to a more fine art paradigm? Which may well be what’s alienating Russ.

Correcting a typo above– Jacob’s and my collective. Carleton Graphic was much more his endeavor than mine, though I helped out!

I’d say the additional focus on format (and fetish,) of the physical object of the ‘book’ or ‘scroll’ etc., which RM writes about here, definitely ties into a move to a fine art paradigm. While I wasn’t there for it, my guess is that the 80s comics scene saw the booklet more as a vehicle for the comics, as opposed to an inextricable part of it.

However, fine art is only a small part of the shift… I think people’s nostalgia for the physical ‘zine’ booklets may have played a larger part.

“the market has moved from comics hobbyists to a more fine art paradigm?”

I’d say that’s pretty accurate, at least with the range of comics I interact with.

Sorry I haven’t been able to chime in here for the past few days, as I’ve been busy this weekend. But a quick look as some recent responses, there was a lot of experimentation going on during the 1980s, ranging from mainstream-ish comics to stuff that was on the cutting edge of what was new and innovative in that era.

Suat–I think it’s the height of irony that I got beat up endlessly the past decade or more arguing that being a commercial artist did not disqualify one from being a “true” artist, and now I’m forced to argue that creators creating art for art’s sake in the 1980s were “truer” artists than some of the SPX folks who seemed to me to be entrepreneurs first and artists second.

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 9/25/13: Convention culture comes crashing to a halt with PalmCon — The Beat

Russ – Just because you did not see the creators trading books at SPX doesn’t mean it wasn’t happening. There were plenty of hand-colored books at SPX. Just because you didn’t see them doesn’t mean they weren’t there.

RM is right. A cursory look at SPX “swag reports” reveals how many artists got books from other artists in trades. Indeed, there were several years where artists actually wore pins that say “I accept trades”. Some artists scold others for giving away books.

Russ is right that there were plenty of books at the show, which has a lot to do with more micropublishers putting money behind books. However, if you couldn’t find an arm’s worth of comics priced from 3-5 bucks, then you weren’t looking. Hell, at the Oily Comics table, nearly everything was a dollar (for an 8-16 page comic).

Certainly, people were looking to make money. That’s why they came to the show. The people in the 80s were looking to make money as well, if they could.

Finally, ascribing the Newave collection to “Fantagraphics” is nonsensical, especially when you try to ascribe it to the Comics Journal. It was edited and collected by Michael Dowers, who was a part of the scene. You can take issue with his choices, but at least he was there as well.

Rob — Most people who published small press comics during the 1980s did not do it to make money. And the few that did were deluding themselves.

And Rob, didn’t you publish or contribute to small press comics back then? I seem to remember that you did. And if that’s the case, you ought to know better.

As for the Dowers book, Fantagraphics published it, didn’t they? And that was my gripe with them back in the 1980s anyway, regarding small press. Their coverage of it was half-assed, at best. A brand new, vibrant, grass roots comics movement was brewing – one based more on the act of creating, and camaraderie with other creators, than anything else — and Fantagraphics was focused primarily on mainstream and independent comics.

As I told Noah, I’m going to pull out my 1980s small press collection and lay it all out in an article. The few snippets of stuff currently out there is nothing, yet many of the current small press crowd seems eager to frame what was an entire movement by what amounts to the briefest glimpse.

Russ, I think you’ve got the wrong end of the stick here. I’m not trying to frame the small press movement of the 80s – you are. What I’m reacting to is your attempts to point out the differences by providing counter-examples. The kinds of things that you saw in the past were still in the room.

Yes, there are differences. But the differences that you are citing boil down to three decades of progress in production values, the ability to present stuff on the internet for the merely curious and the rise in microbusiness – all advances that would probably have been utilized had they been around in the 80s.

For someone who just walked into the room for the first time, these changes can be jarring. But the content is not fundamentally different, nor are the motivations. In fact, I think that it would be easy to argue that a sizable percentage of the creators at SPX are deluding themselves about their ability to make money.

I fully accept that you understand the small press of the past better than I do – your credentials are not under attack in any way shape or form. But when you were asked to provide examples to support your thesis, you provided bad ones (by your admission). If they were bad examples, perhaps you shouldn’t have provided them?

“If they were bad examples, perhaps you shouldn’t have provided them?”

I dunno; when you’re in the middle of a conversation on the internets you might not take as much time as you might like ideally, right? That seems pretty natural. That’s why I asked Russ to do a post for us; so maybe we can take this up again then.

RM — I’m obviously framing the two because I think there IS a difference. And it isn’t some cloudy nostalgia. Keep in mind that I was a fanzine publisher during the 1970s, and had basically dropped out of publishing. I was still occasionally contributing to ‘zines, but I had moved on to other things — that is, until I stumbled on the small press boom in 1985. It was different than the 1970s. The burst of energy, freshness and creativity was palpable, and was a welcome respite from mainstream and independent comics. Better still, small press stuff was CHEAP, making sampling easy and painless. And the painless part was important then, because most of the independent comics back then, and even a big chunk of mainstream stuff, was crap. I don’t know how many times I heard comics fans/dealers lamenting how they’d ordered this or that new title, only to find out when they actually got it, it reeked.

SPX didn’t radiate the same vibe, in my opinion.

Russ, I was a young teenager in the early 80s and certainly didn’t publish anything in the small press comics movement.

Fantagraphics publishes lots of things that The Comics Journal doesn’t necessarily agree with, especially if by “TCJ” you mean “Gary Groth”.

Now, if your issue is that TCJ in the 80s ignored or weren’t aware of the small press movement, you may well be right. But the Newave book was Michael Dowers’ vision, so if you have complaints, you should take it up with him, not Fanta or TCJ.

Regarding money, the vast majority of the people in the room at SPX were looking to break even. Trust me, maybe 1% of the artists in the room actually make a living doing comics. That may well be different from the small press comics of the 80s, but if a comic appeared in a catalog, they were selling them and expecting some small amount of money back.

I obviously can’t change your mind about the vibe you got from SPX, but the reality is different from your perception.

Finally, a suggestion. You should try and reprint the best of the small press from the 80s, especially the most interesting things left out of Dowers’ book. Or convince Steve Willis to do a collection. The 80s and 90s are the last era where there’s a large chunk of interesting comics that have gone out of print and out of mind, especially now that the Golden Age of Reprints seems to have caught up to so much stuff.

Rob — I like the idea of a broader sampling of Steve Willis’ work beyond what was in Dowers’ book (which wasn’t much). We corresponded a bit back then, and in addition to ordering everything he had, I kept my eye open for his new stuff whenever it popped up. So I have 15 or so of his 1980s publications. and that stuff is so radically different than most small press stuff (then and now) it really needs a wider audience.

By the way, being a “young teen” during the 1980s certainly wasn’t a show-stopper for contributing to/publishing small press stuff back then. Gary was something like 14 when he started self-publishing, as was Bill G. Wilson. But I digress…

The prices and slick stuff prevalent at SPX made my eyes water, and I’m not exactly destitute.

I’ll buy that, Noah.

I agree that there was a lot of overpriced stuff at SPX. It is very easy to spend waaaaay too much money there if you are not careful. And there is a lot of crap, no doubt about it. These are people working the biggest open mike night in indie comics and not all of them are going to be polished.

One of the less obvious things at SPX is the amount of webcomics creators there were in attendance. In theory, anyone with a smartphone can pull up a creator’s website and bookmark it for later examination. There’s a reason that a lot of people hand out free fliers and business cards – always have something free on the table.

The show even had a list of websites next to the creators names. A dedicated individual could have gone through the entire list beforehand and see what looked good to make the shopping easier. I’ve never met this individual, but anything is possible.

RM: I am indeed that individual who looks at every website before the show, or at least of the artists whose work I’m not familiar with. It’s the only way I can handle the size of the room. I generally tend to find that at SPX, I am not interested in 2/3 of the creators present. Of course, at this year’s show, that meant there were still nearly 300 artists I wanted to see!