The cover of the 1965 Paperback Library novel Adam Link—Robot,

which collects Otto Binder’s Adam Link stories from the late 1930s and 1940s.

As I watched and enjoyed the new Spike Jonze science fiction film Her, I began to wonder, What would Otto Binder think of this? Although best known to comic book readers and scholars as the writer of Captain Marvel and Superman, Binder began his career as a science fiction writer, first in collaboration with his older brother Earl. The pair began publishing under the pen name Eando Binder (Earl and Otto) in the early 1930s. By the time “I, Robot,” the first in a popular series of adventures featuring the artificial man Adam Link, appeared in the January 1939 issue of Amazing Stories, Otto was writing on his own, but retained the Eando Binder byline.

In science fiction circles, Otto Binder’s best-known work remains the Adam Link series, which served as the inspiration for Isaac Asimov and for countless other writers exploring the idea of artificial intelligence. Over the course of his comic book career, Binder adapted some of the Adam Link stories for EC Comics in the 1950s and again for Warren Publishing’s Creepy in the 1960s. When Qiana invited me to contribute another guest post for Pencil Panel Page, I began to think again about her December 2011 essay “Can an EC Comic Make ‘You’ Black?” and what it might tell us about Otto Binder and Joe Orlando’s adaptation of “I, Robot” from Weird Science-Fantasy Number 27 (dated Jan.-Feb. 1955). In the EC version of “I, Robot,” Binder’s use of the second-person you places the reader in a complex position: as we read the story, do we identify with the hero, Adam Link, or with the violent mob threatening to destroy him?

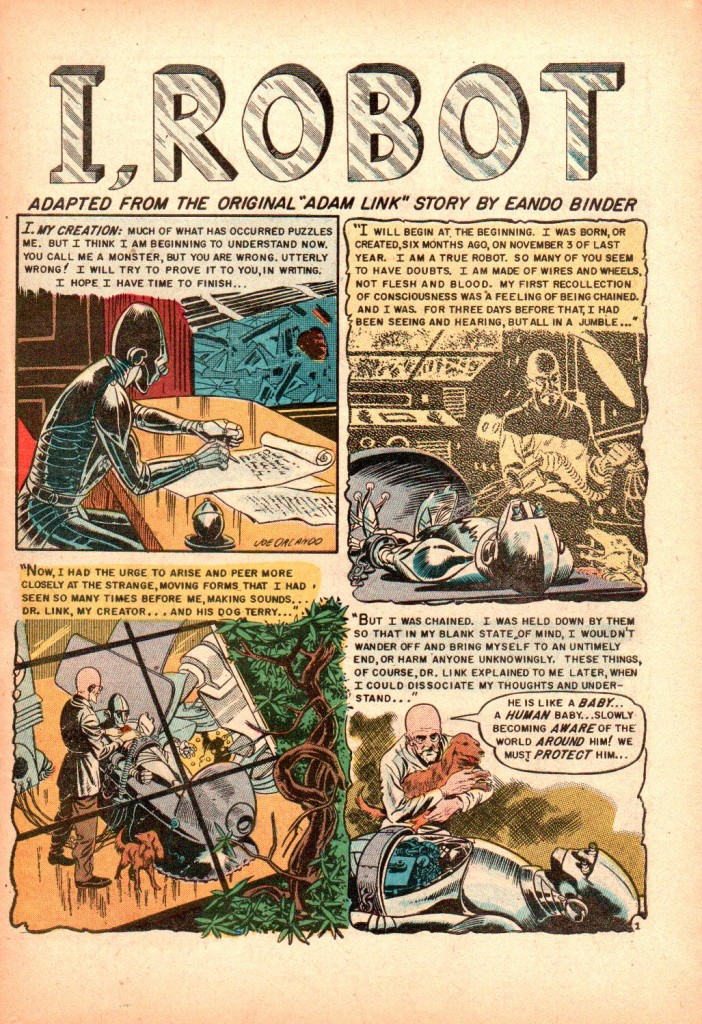

The first page of Otto Binder and Joe Orlando’s adaptation

of “I, Robot” for EC’s Weird Science-Fantasy Number 27 (Jan.-Feb. 1955). Colors by Marie Severin.

In a letter to science fiction fan and editor Sam Moskowitz dated October 4, 1952, Binder discusses the scripts he’s been producing for EC Comics. He explains that he’s “gotten into the groove on thinking of [science fiction] plots for them, even if they are more simplified and corny than what would go into a pulp.” Binder then appears to reconsider his summary of EC’s science fiction and fantasy comics and adds the following parenthetical comment:

(But a suggestion….pick up a copy of WEIRD FANTASY or WEIRD SCIENCE comics sometime and read them….the comics are not too far behind the pulps in well-plotted stories, believe it or not!)

In the early 1950s, after over a decade as a prolific comic book scripter, Binder was hoping to return to the science fiction market and was looking to Moskowitz, to whom he later left the bulk of his personal and professional correspondence, for advice and support. As Bill Schelly notes in his excellent biography Words of Wonder: The Life and Times of Otto Binder, the writer had to make some adjustments to his style when he began working for EC: “Binder’s job, as he saw it, was to emulate the writing style of Al Feldstein, who always put lots of lengthy captions into the scripts. This wasn’t Binder’s normal inclination, but he did his best.” As a freelance writer, Binder survived by adapting himself and his style to suit the requirements of his publisher and of his audience. As he explained in the letter to Moskowitz, “Now I have no prima-donna qualms about accepting ideas from an editor….it doesn’t violate my lone-wolf sensibilities. In fact, in the comics, editor and writer often whip up ideas between them.”

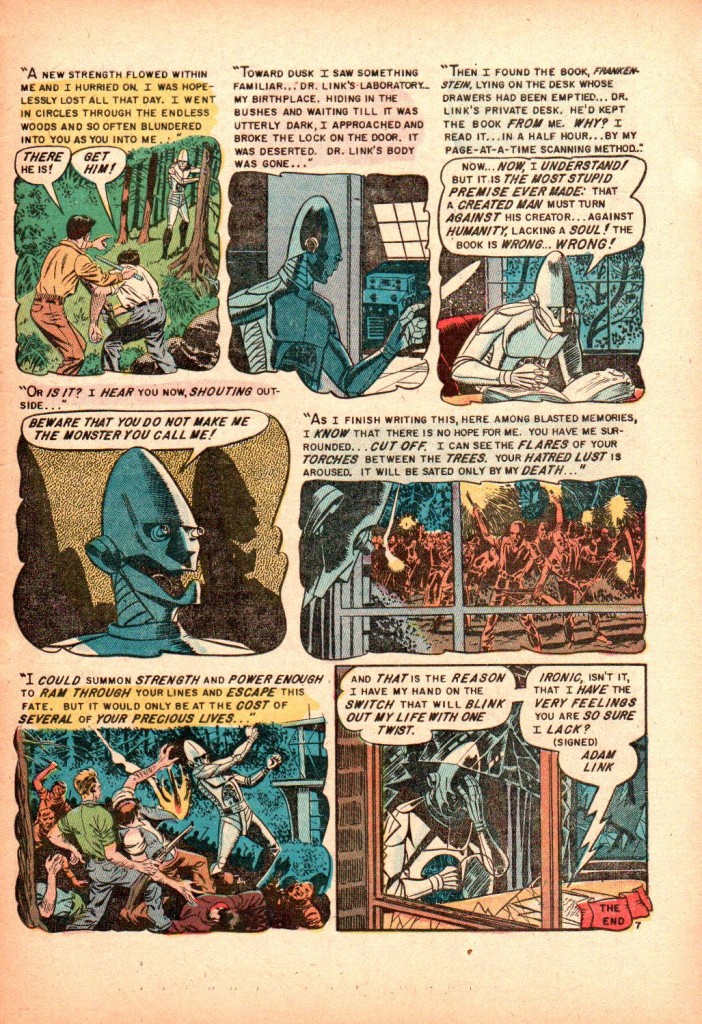

While in both the EC adaptation of “I, Robot” and in the 1939 original, Binder employs first person point-of-view as Adam Link tells the story of his creation, by the end of the Weird Science-Fantasy version, Binder shifts to the second-person as the robot addresses his tormentors—and, by extension, those of us reading the story. On the final page of the 1955 “I, Robot,” Adam Link, wrongly accused of murdering his creator and surrounded by an angry mob, exclaims, “Beware that you do not make me the monster you call me!” In his journal, he writes, “As I finish writing this, here among blasted memories, I know that there is no hope for me. You have me surrounded…cut off. I can see the flares of your torches between the trees. Your hatred lust is aroused. It will be sated only by my death…”

The final page of the 1955 EC Comics adaptation of “I, Robot.”

Those two panels in the center of the page pose an interesting challenge for the reader: first, Orlando and colorist Marie Severin ask us to identify with Adam Link, whose long, cylindrical forehead and mechanical jaw cast distorted shadows on the yellow wall behind him. He is, for a moment, almost human, as he makes a plea not to be turned into a monster by humanity’s hatred and violence. The text that appears over the panel, however, tells us, “I hear you now, shouting outside…” While we might sympathize with the protagonist, especially after the loss of his dog Terry on the previous page (in the original story, as the mob fires on Adam, a stray bullet kills the dog), we also, for a moment, inhabit the role of the aggressor.

The next panel is even more fascinating. We share Adam Link’s point-of-view as we stare out a window at the men, most of them carrying a rifle or a torch or both. Just two panels earlier, we saw Adam Link before that same window, reading his creator’s copy of Frankenstein. Now, however, the scene has changed, and we stare with horror at the grotesque figures that approach Dr. Link’s laboratory. Again, the text box disrupts our sense of identification with the robot: he addresses us directly. We are part of the mob. As we stare out the window, we are looking not at a display of “hatred lust” and impending “death” but at ourselves, and our petty hatreds and small-minded prejudices.

“I, Robot” inverts Qiana’s original question and seems to ask, Can this EC comic transform you, the reader, into a lustful, bloodthirsty, bigoted villain? Or have Otto Binder and Joe Orlando merely held a mirror up to EC’s audience, one they hope will challenge readers to reflect more deeply on issues beyond the fantastic realm of the comic itself?

Binder addresses these issues in another EC adaptation of one of his earlier science fiction stories, “The Teacher from Mars,” also drawn by Joe Orlando and colored by Marie Severin for Weird Science-Fantasy Number 24 (dated June 1954). As Schelly points out in Words of Wonder, Binder selected “The Teacher from Mars,” first published in Thrilling Wonder Stories in 1941, for Leo Margulies and Oscar J. Friend’s 1949 collection My Best Science Fiction Story, which includes stories from Isaac Asimov, Robert Bloch, and Harry Kuttner. In his introduction, Binder explains that “the story,” in which human students abuse and terrorize their Martian teacher, “was a good medium for showing the evils of discrimination and intolerance. Sadly enough,” he continues,

we have not yet eliminated those degrading influences on our world. The Martian in this story is the symbol of all such reasonless antagonism between “races.” Not that I wrote the story solely for that reason. It just happened to strike me as the best “human interest” approach. The “moral” was incidental.

In most of his work, from the Captain Marvel stories of the 1940s through his Superman narratives in the 1950s and even his scripts for Gold Key’s Mighty Samson in the 1960s, Binder again and again sought to explore what he refers to as the “‘human interest’ approach.” As Bill Schelly has argued in his comments on “The Teacher from Mars,” “Though Binder denied that the anti-discrimination sentiments in the story were his main reason for writing it, they are there nonetheless.” Therefore, is the “moral” really “incidental” in “I, Robot” or “The Teacher from Mars”? And what does Joe Orlando’s work bring to these comic book versions of Binder’s original short stories?

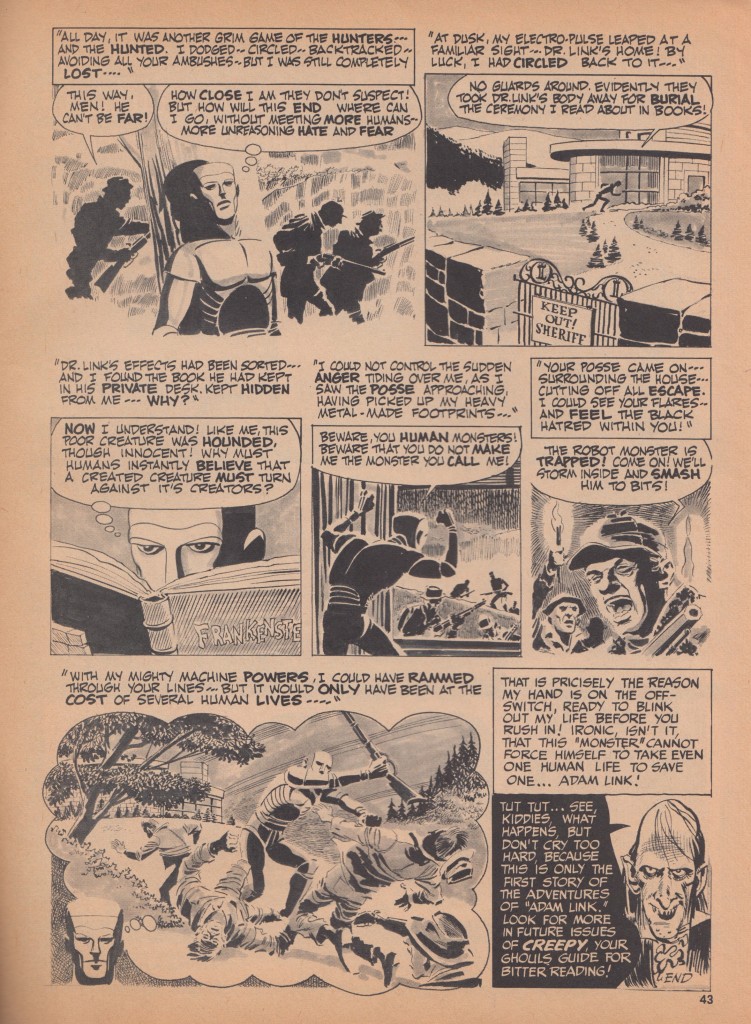

The final page of Binder and Orlando’s adaptation of “I, Robot” for Warren Publishing’s Creepy

No. 2, 1965 (page 43).

The EC version of “I, Robot” raises interesting questions, not only about adaptions of prose works into comic book form, but also about the moral imagination of creators like Binder and artist Joe Orlando. The complexity of the point-of-view in Adam Link’s narrative might be read in light of a passage from James Baldwin’s essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel”:

The failure of the protest novel lies in its rejection of life, the human being, the denial of his beauty, dread, power, in its insistence that it is his categorization alone which is real and which cannot be transcended.

How might Baldwin’s critique of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the “protest novel”—a work of fiction that sets out to raise consciousness and fight social injustices—help us to read the many versions of Binder’s “I, Robot”?

One possible answer is this: because the story of Adam Link is a very obvious fiction, one built, as Binder himself admitted in the January 1939 issue of Amazing Stories, on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, it makes clear its status as a work of the imagination—that is, as a text (you can read more of Binder’s introduction to the original “I, Robot” in Schelly’s biography). “I, Robot” makes no claims to realism or verisimilitude. It might be read simply as an engaging adventure, or as a moral lesson on our jealousy, hatred, and ignorance. But we might also place the multiple versions of Binder’s story in dialogue with each other as well as with other texts from the era in which they first appeared. The January, 1939 issue of Amazing Stories, for example, appeared just a few months before the first publication of James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” another relic of the period that continues to fascinate American audiences in the form of Ben Stiller’s new film. As we explore the shape and the dimension of the society in which Binder lived, we have an opportunity to investigate how his America shaped our own. And as we read this comic book from 1955, Adam Link continues to address us, even now, as, in the closing lines, he remarks, “Ironic, isn’t it, that I have the very feelings you are so sure I lack?”

Last week, after we saw Her at the Landmark on the corner of Clark and Diversey in Otto Binder’s old hometown of Chicago, I wondered, What would Binder have thought of this 21st-century story of the love between a middle-aged man and his operating system? And what does Binder’s “I, Robot” in all its forms—from the original story to the later EC Comics and Creepy versions to the novel Adam Link—Robot Binder published in 1965—ask of us as modern readers and as comics scholars?

References and Further Reading

Baldwin, James. “Everybody’s Protest Novel” in Notes of a Native Son. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984.

Binder, Eando. Adam Link—Robot. New York: Paperback Library, Inc. 1965.

Binder, Otto. Letter to Sam Moskowitz. October 4, 1952. Courtesy of the Otto Binder Collection, Cushing Library, Texas A&M University.

Binder, Otto. “The Teacher from Mars” in Leo Margulies and Oscar J. Friend, My Best Science Fiction Story. New York: Pocket Books, 1954. 18-36.

Schelly, Bill. Words of Wonder: The Life and Times of Otto Binder. Seattle: Hamster Press, 2003.

You can also read Noah’s discussion of Her and its relationship to Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? at Salon. Qiana’s paper at the 2013 Dartmouth College Illustration, Comics, and Animation Conference, “Science Fictions of Race in EC’s ‘Judgment Day,’” was another inspiration for this post.

I’m curious what you liked about Her, Brian. I hated that movie.

I don’t know how enthusiastic I am about these Adam Link pages either. I guess it feels to me pretty much like you’re straightforwardly supposed to identify with Adam Link here. The use of “you” doesn’t change that much, I don’t think. The narrative has you there with Adam, and he’s the sympathetic one; the narrator whose consciousenss you’re in. The use of “you” seems like it just further cements you there with him; the reader is speaking the “you” with him, identifying the mob out there as the enemy.

I also don’t find the story as presented very thoughtful. The lynch mob is so clearly evil that no one would see themselves in them. The robot is so noble — willing to sacrifice himself for his tormentors — that it makes it seem almost like if you’re different you have to be a paragon of self-sacrifice to deserve any sympathy at all. It’s just too much of a binary to function as a thoughtful take on anything.

Again, I feel like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is way more interesting. There you’re not sure who is an android and who isn’t; the androids are in fact different in a lot of ways — and then whether they are or not is repeatedly complicated. You’re mostly in the head of the murderer, though with an occasional detour out so that his actions (and your identification with them) are thoroughly compromised. It seems like a much more subtle take.

Thanks for the comment, Noah! As I was watching the new Spike Jonze film I had in mind the BBC documentary _Synth Britannia_ and a comment Daniel Miller makes about J.G. Ballard’s writing. He says that one of the elements he admired about Ballard was a sense that the stories take place “five minutes into the future.” I had that sense watching _Her_, especially because of the production design, the somewhat cold but precise cityscape that surrounds and engulfs most of the characters–with the exception of Scarlett Johansson’s Samantha.

I was also taken with the characters’ costumes, which, for me, had a nostalgic, retro-futuristic quality. I kept reading all of those signifiers as allusions (conscious or unconscious) to those Depression-era science fiction writers, like Binder or early Asimov. As Svetlana Boym points out regarding nostalgia, it’s sometimes a longing “for the unrealized dreams of the past and the visions of the future that became obsolete.” So as I suppose I watched _Her_ in the same way that I read something like Ballard’s _Concrete Island_ or “The Dead Astronaut”–as an exploration of ruins or relics, old notions of robots in love and gleaming, perfect, somewhat repellant but compelling urban spaces.

And, since Paul Thomas Anderson’s _The Master_ has become one of my favorite films, I’ve started watching Joaquin Phoenix more carefully. His character in _Her_ almost seems like a variation on Freddie Quell from Anderson’s film. And I love the names of these characters. When we finished watching _Her_, we kept wondering if his character’s name, Theodore Twombly, was some sort of riff on Cy Twombly’s guileless paintings.

It’s been at least 25 years since I read _Androids_, maybe longer, so I don’t have a clear recollection of the book! Although I’ve enjoyed the other Dick novels I read–I read _Valis_ and _The Divine Invasion_ a few years ago–I find him somewhat opaque. I don’t get the same jolt from his writing, say, that I do from Ballard or Anna Kavan or even some late 60s Robert Silverberg, all of whom I think of as working the same territory he does in his novels. But that’s my shortcoming, not his.

As for Binder, I think he very clearly saw his audience, even at EC, as being fairly young. This often means that his characters, at least for adult readers, will seem somewhat simplistic–although this is not always the case, for example, in his Captain Marvel stories, especially the Mr. Tawny series. But when I read Alan Moore’s comments on superhero comics in his interview in The Guardian in November, I immediately thought of Binder. Moore says that superheroes “don’t mean what they used to mean. They were originally in the hands of writers who would actively expand the imagination of their nine-to-13-year old audience. That was completely what they were meant to do and they were doing it excellently.” So I think of Binder as a writer who did work in binaries, but I believe he did so in part for the audience he saw himself as addressing, one much younger than the readers of the pulps he’d written for in the 1930s.

As for the self-sacrifice, I read that conclusion to the _Creepy_ version as much more ominous–that Adam Link is so far removed from human culture his only option is the contemplation of suicide. Binder plays with some of those ideas of alienation and self-destruction in the Mr. Tawny stories, too, especially in the early 1950s. Was Binder as subtle as Henry Kuttner or C.L. Moore (I’m thinking of them because one of his editors in the early 1950s recommended that Binder read Kuttner’s work to familiarize himself with more contemporary styles of science fiction)? Definitely not, but that is perhaps why his most lasting work, I think, is in the comics work he did at Fawcett and later at DC–those scripts written for the younger audience Moore talks about in that interview.

I’ve only read one Kuttner and Moore work, I think, but it’s wonderful. (Wrote about it here a bit back.)

It sounds like you’re responding mostly to the design and visuals with “Her”. Most of my problem was with the narrative…though I think I did pick up on the kind of winsome nostalgia you enjoyed. It’s kind of curdled for me, I’m afraid; it all ends up as a greeting card cute evocation of the essential sweetness and iconicity of middle-class white guys and their mid-life crises. (And to no one’s surprise, I kind of hate Cy Twombly too, in all his deliberate guilelessness.)

I haven’t read a ton of Silverberg, but Ballard and PKD are really, really different. Ballard’s apocalyptic, hip, visionary, and very consciously avant-garde. PKD’s none of those things, really. It’s the difference between a world hurtling towards destruction and a world where the seams don’t quite fit, quietly and unsuccessfully trying to stay together. I much prefer the second, but I could see how PKD wouldn’t make much sense if you were looking for the first.

Brian, thanks for this post and for giving me a reason to go back to read “I, Robot.” (I wasn’t familiar with the Creepy version and would love to see the whole thing!)

In thinking about your question, I have a couple of thoughts. I’m struck by the fact that Adam Link’s last act in response to the angry mob is to end his own life – or rather, that his hand is “on the off-switch” – in order to avoid violent retaliation against humans. The move aligns “I, Robot” quite fittingly with Baldwin’s reading of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, more so than I initially thought. The robot’s self-sacrifice and humility are the only things that can affirm his artificial “humanity” while conveniently ensuring that he never benefits from it.

In Stowe’s case, this kind of strategic sentimentality may give the impression that the reader is meant to relate to Uncle Tom, but as Baldwin points out, the goal here is not really empathy, but repentance and the kind of catharsis that can displace meaningful engagement. I’m guessing that you agree, Brian, that there is a similar “theological terror” that drives Adam Link’s account (right down to the flames and torches that surround the mob). But I have to say, I’m not sure we’re ever meant to identify with the robot at all, based on the story’s construction… it’s no accident that Adam’s so-called first-person account is quoted from a letter he’s writing. We – the mob of humanity/humanity as mob – are the recipient…. I mean, why even have the quotes at all? Other EC stories sustain the first person account through the entire narrative and don’t use quotes. The quotes keep Adam at a distance.

Also, on another note: Binder’s resistance to the “moral” reading is really interesting and sounds so much like Feldstein’s and Gaines’s own insistence that all EC stories were first and foremost to entertain. I’ve been thinking a lot about why the writers/artists go through the trouble to make this point. But the way Baldwin eviscerates Stowe (and by extension Wright) as not a novelist but an “impassioned pamphleteer” offers some potential clues as to why comic book writers are so quick to deny that social protest played any role in their storytelling… even when working in a genre like sci-fi that invites these kinds of metaphorical parallels all the time!

I doubt that comic book artists at the time were exactly worried that people would think of them as pamphleteers and not serious artists — nobody thought of them as serious artists anyway, did they? I can see them wanting to avoid charges of politics for bottom-line reasons, though, maybe; safer not to have a message and just be entertainment, and then no one will bother to censor you.

Well yes, I agree that the denials were part of a larger marketing strategy and a way to deflect industry oversight (at least initially). But EC made special claims about the quality of their storytelling and in the quote from Binder above, he takes his artistic choices very seriously. I’m not discounting the bottom-line reasons, but there’s a stigma attached to “moralizing” that seems to me to be older and deeper than just this one industry.

Thanks for the comments, Qiana! I’ll have to make you a copy of the rest of the Warren version of “I, Robot.”

I’m still curious to know how much influence Al Feldstein had over the script for the EC version. I wonder, for example, if, as Schelly points out, Binder attempted to imitate Feldstein’s style or, in this case, if Feldstein rewrote the ending and added the shift to second-person in the narration. Also interesting is the fact that in the 1965 collection of Adam Link stories, the robot doesn’t attempt to switch himself off as he faces of the mob. Rather, the first story ends with the following paragraph:

“Clubs and guns were raised against me. Hate was in their faces. I closed my eyes, to shut out the sight. It was the end, my thoughts said, of Adam Link, the first of intelligent robots–and the last.”

I’m still trying to track down the 1939 original from Amazing Stories, so I don’t know if that version has a different ending than the 1965 Paperback Library edition. My reading of this later version has no doubt shaped my feelings for Adam Link–in the prose version, there’s no question that Adam is the focus of our sympathy. Because we have to imagine the terror of what the robot is facing, without the drama of Joe Orlando and Marie Severin’s visuals, we readers become Adam’s confessor, his confidant.

In the short story Binder is also much more interested in Adam’s status as a citizen, as his creator, Dr. Link, trains and educates him to take his place in human society. Towards the end of the narrative, Adam remarks, “Adam Link, American citizen? No, it was Adam Link, Frankenstein monster.”

And, as Qiana suggests, Binder took his craft very seriously. I don’t know if I’d say he saw himself as an artist–he was too modest, I think, to make those claims for himself–but he definitely saw infinite potential for comics as an art form. Schelly points out that, in the early 1940s, Binder was already writing about the narrative potential of comics in an essay published by a science fiction fanzine called Sunspots. He followed up with more letters and interviews on the potential of comics in the fan press of the 1960s. Like his friend and collaborator C.C. Beck, he already had almost a decade of professional experience when he began writing comics. In addition to his experiences in the pulps, he’d also worked for Otis Adelbert Kline, the writer and literary agent who represented Robert E. Howard. So, like other writers of his generation, he approached his work pragmatically, but also saw it as a means of entering the middle class, not only financially but also, perhaps, culturally or intellectually. In that sense, he reminds me very much of Jack Kirby, who in interviews will talk in very lofty terms about his work but will also bluntly state that he was also motivated because he “had to make sales,” as he says in the great interview with Ken Viola for Masters of Comic Book Art from 1987:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M50Mjdsh_iw

So I think the most compelling writers, artists, and editors of the 1940s and 1950s–people like Gaines, Feldstein, Binder, Beck, Ramona Fradon, Matt Baker, Mac Raboy, Harvey Kurtzman, Bernard Krigstein, to name just a few–were working with a form in which there were very few rules, as long as the books sold. In order to appeal to readers–to “make sales”–they believed, as Kirby also says in that interview, in telling “people stories.”

Then again, to build on Qiana’s point, I find the same resistance to talk of moralizing or protest in Bob Dylan’s interviews. I’m teaching a course on Dylan this semester so I’ve been thinking of his “protest” period, which we’ll use to start the semester in a couple of weeks. Since the 1960s he’s been adamant in interviews that he’s never seen himself as a protest singer and, of course, once famously described himself as “a song-and-dance man”!

Brian, there’s a Swedish tv show called Real Humans you might be interested in too. I watched the first episode last night, and was startled at how deeply it speaks to the issues you’re addressing above.

Thanks, Chris! I hadn’t heard of the show. It looks really interesting. I’ll see if I can stream it from iTunes.

Speaking of TV shows, I forgot to mention the 1964 Outer Limits adaptation of “I, Robot,” written by Robert C. Dennis and starring Leonard Nimoy. You can watch it on Hulu:

http://www.hulu.com/watch/155117

It was adapted again for the 1990s version of Outer Limits. The 1964 version aired just a couple of weeks after that other classic android/robot story, Harlan Ellison’s “Demon with a Glass Hand,” which was filmed in the same building Ridley Scott used as a set for sections of Blade Runner.