This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007 . A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

______

As an artist who does erotic artwork for a living, there are certain questions that I inevitably get asked, whether it’s in the context of an online interview, a first-time studio visit or just hanging out at a party. One that I can pretty much count on every time – along with “Have your parents/family seen your books?” (answer: yes) and “Have you tried any of the things you draw in real life?” (answer: yes again) – is “What inspires you to draw this kind of artwork?”

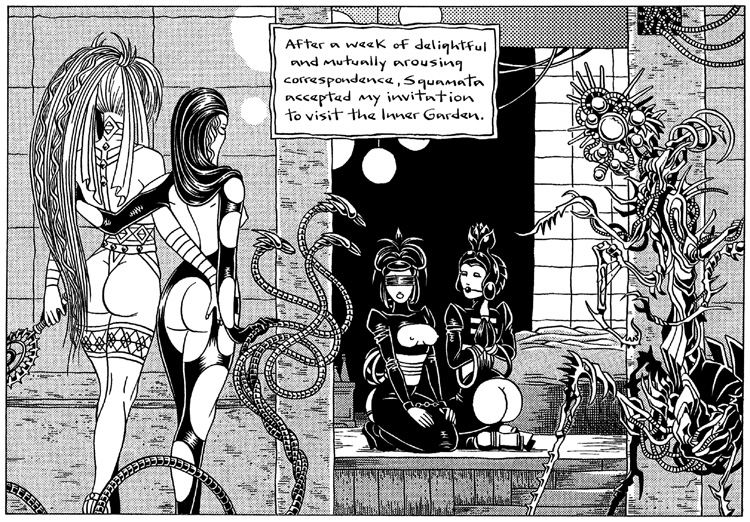

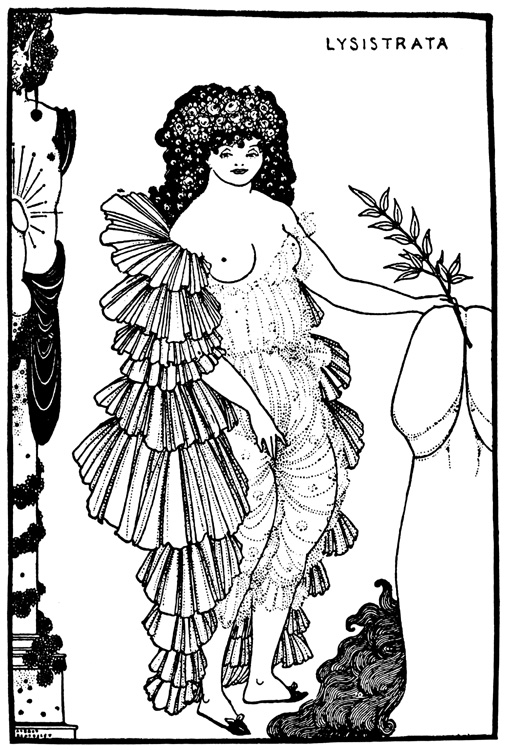

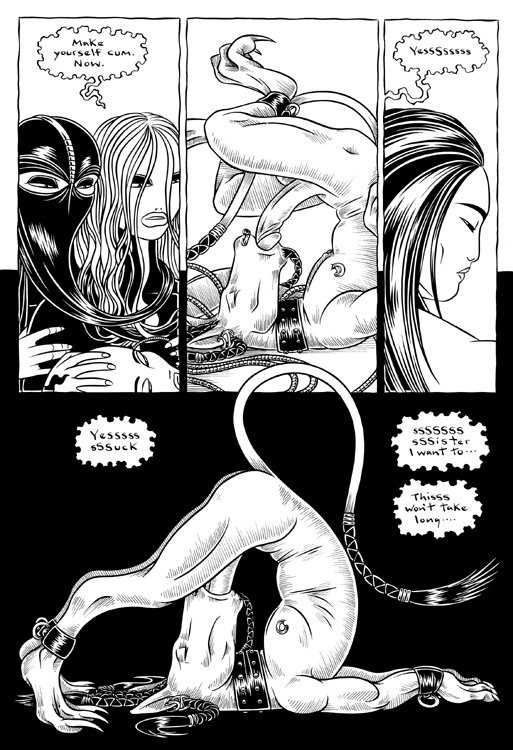

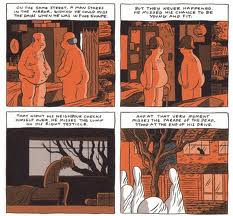

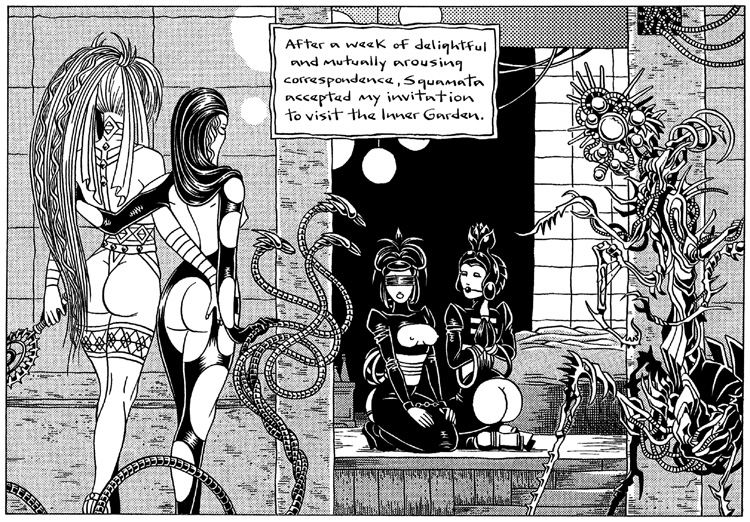

From In a Metal Web II, ©Michael Manning

The first things that come to mind are the usual suspects: life, death, sex, the work of other artists. One influence that isn’t always so obvious is music. I listen to a lot of it, usually while I’m working. I like seeing live music too. A good live show can provide weeks worth of inspiration. For all the styles and sub-genres of music that I like though, I’m aware that there are many many more that I know very little about. Opera, for example. I own a grand total of one disc (excerpts from Puccini’s La Boheme) and am more familiar with the story lines courtesy of P. Craig Russell’s comix adaptations and viewings of Amadeus and Immortal Beloved than I am with the actual music. None of my music collector friends are opera fans. Also, I’ve always had the impression (misguided or not) that opera, like free jazz or death metal, is something best experienced live and the astronomical ticket prices can be very intimidating.

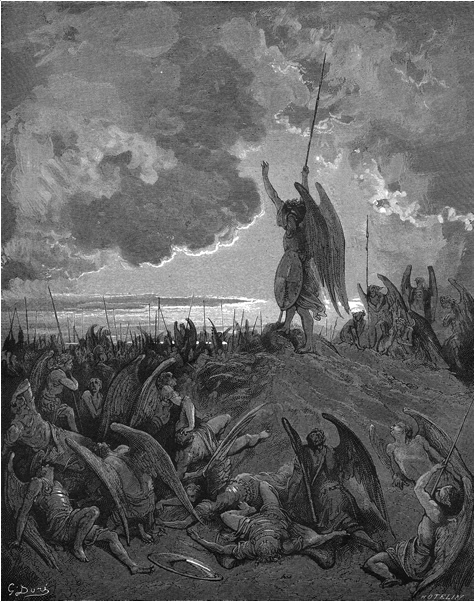

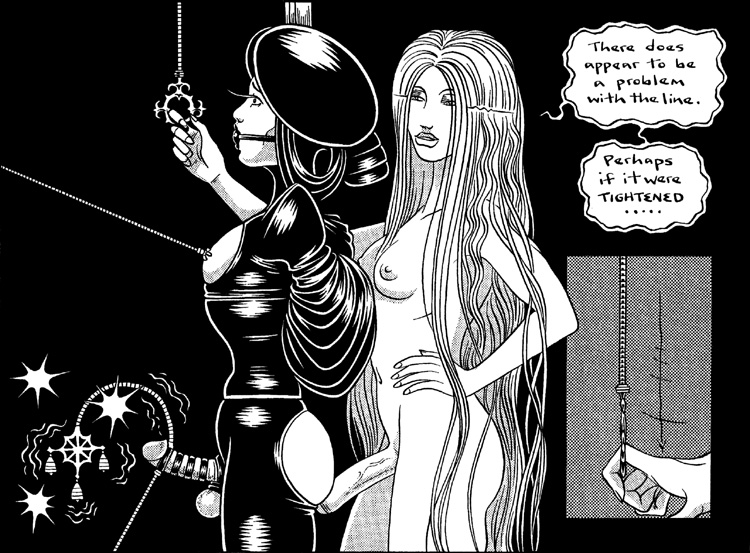

From In A Metal Web I, ©Michael Manning

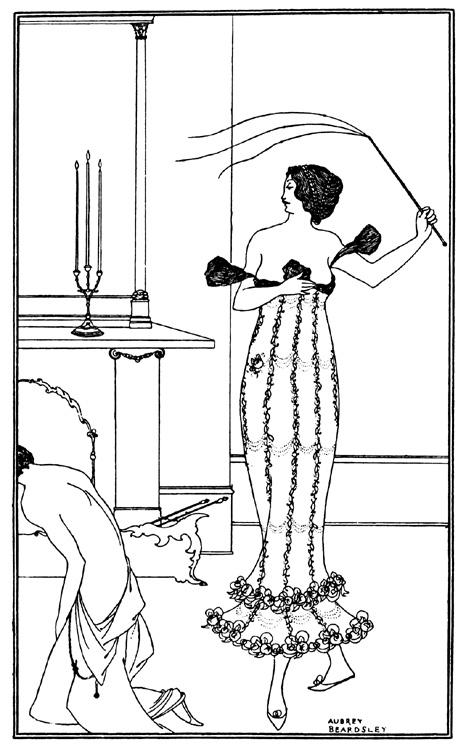

Last year, two things tipped the balance toward my first opera experience. One was a generous anniversary gift from Lyn’s father that we decided to reserve for something that we couldn’t ordinarily afford to do. The other was a locally-produced version of Wagner’s Tannhäuser — a classic operatic meditation on the struggle between the sacred and profane — which supposedly featured nudity and an big orgy scene. And so one March evening, we found ourselves in the vertigo-inducing cheap seats in the fourth tier of the cavernous Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in downtown Los Angeles. Sure enough, the beginning of act one did consist of a twenty minute long sex party with many lovely toned mostly-nude bodies engaging in various acts of simulated copulation, writhing away on two rotating stage sets, all bathed in the crimson glow of Venus’ underworld. Most of our favorite positions and permutations were featured in a variety of gender combinations with special attention paid to trios, doggy-style fucking, pussy/ass/foot worship and even a bit of flogging. It was all good NC-17 rated fun, but the whole time, I couldn’t help thinking that it wasn’t nearly as naughty as illustrator Aubrey Beardsley’s prose version of Venus and Tannhäuser aka. Under The Hill from 1904.

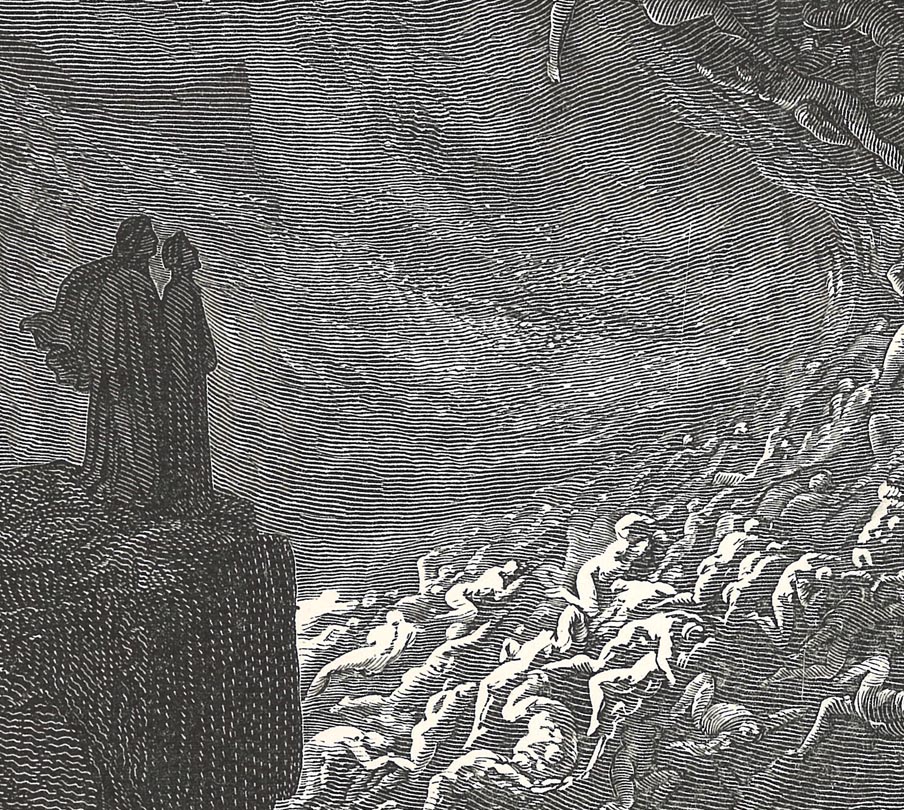

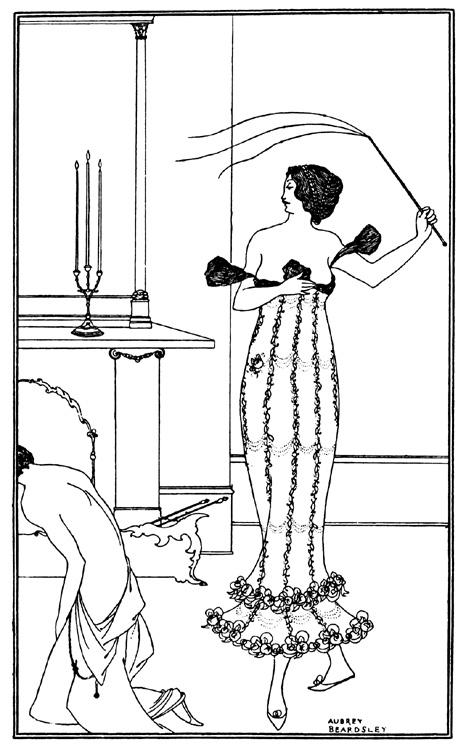

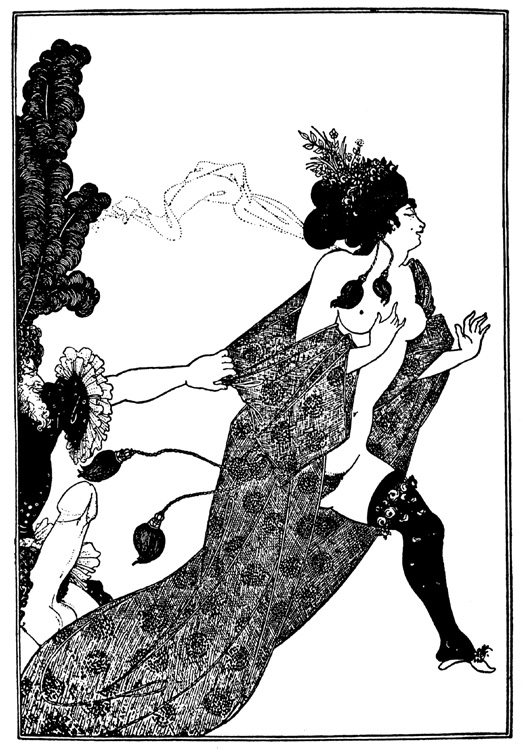

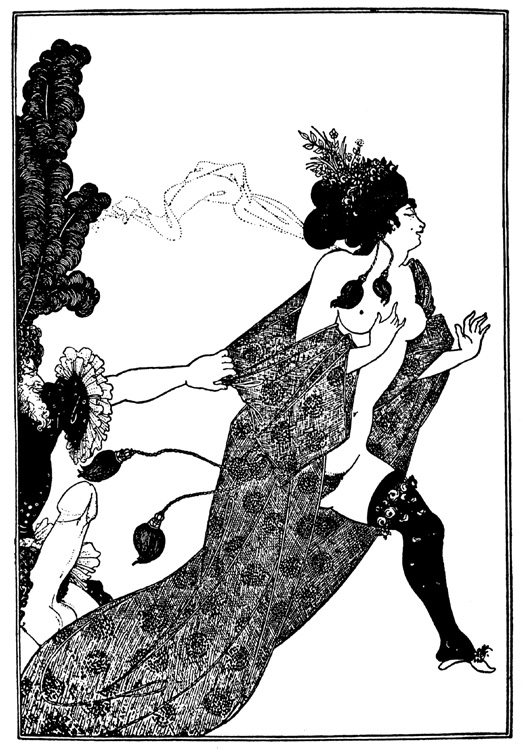

From Beardsley’s frontispiece to Earl Lavender by John Davidson

Now as an artist who does erotic artwork — especially predominantly black & white gender-freaky erotic artwork — it’s difficult to remain ignorant of Beardsley, much less avoid having your work measured against his, even in this day and age when black & white artwork makes most people think of manga or Frank Miller. The o.g. (19th century England, baby) black & white gender-freaky erotic artist, Beardsley was never very well known for his prose yet over one hundred years after its first publication Under The Hill remains one of the dirtiest stories ever told. According to my copy of “Aubrey Beardsley: A Slave To Love”, the text was never completed during Beardley’s life time due to a combination of his ill-health, legal/censorship problems and the scandal resulting from Oscar Wilde’s trial, but hotter heads eventually prevailed, the incomplete manuscript finally saw print and has remained in circulation ever since.

In Wagner’s version of “Tannhäuser”, the first act has barely gotten under way before the titular hero, bored to tears with all this endless carnal pleasure and pining for just one more glimpse of Germany’s apparently unmatchable fields and streams, chooses to spurn the Goddess and gets himself ejected into the outside world. Predictably, he grows to regret his stupid decision and spends two and a half more acts trying to convince the puritanical aristocrats of his aptly named hometown Wartburg that the noblest form of love is the physical (spoiler: he fails miserably). Thankfully, Beardsley’s version chooses to focus on the good stuff; that is, everything that goes down prior to the opera: Tannhäuser’s wooing of the Goddess and Meretrix and their erotic adventures, all told in the most ornate gorgeously overblown prose imaginable.

From the Chapter I – How The Chevalier Tannhäuser Entered Into The Hill of Venus:

It was taper-time; when the tired earth puts on its cloak of mists and shadows, when the enchanted woods are stirred with light footfalls and slender voices of the fairies, when all the air is full of delicate influences, and even the beaux, seated at their dressing-tables, dream a little.

A delicious moment, thought Tannhäuser, to slip into exile.

The place where he stood waved drowsily with strange flowers, heavy with perfume, dripping with odours. Gloomy and nameless weeds not to be found in Mentzelius. Huge moths, so richly winged they must have banqueted upon tapestries and royal stuffs, slept on the pillars that flanked either side of the gateway, and the eyes of all the moths remained open and were burning and bursting with a mesh of veins. The pillars were fashioned in some pale stone and rose up like hymns in the praise of pleasure, for from cap to base, each one was carved with loving sculptures, showing such a cunning invention and such a curious knowledge, that Tannhäuser lingered not a little in reviewing them. They surpassed all that Japan has ever pictured from her maisons vertes, all that was ever painted in the cool bathrooms of Cardinal La Motte, and even outdid the astonishing illustrations to Jones’s Nursery Numbers.

The full version can be read here.

With it’s lavishly decked-out gender-ambiguous aristocrats gamboling in scented baths full of serving boys, bands of satyrs “consummating frantically with women’s bosoms” and unforgettable highlights such as Venus masturbating her well-hung pet unicorn for the enjoyment of her human lover, Under The Hill achieves an unmatched level of camp eroticism and barely-veiled perversity. I wish I could say that it’s playfully unapologetic ultra-baroque polysexuality had some influence on the creation of my Spider Garden books but unfortunately, I wasn’t aware of it’s existence until after I had completed the second Metal Web book.

My first reading of Under The Hill was yet another curve-ball from an artist with whom I’d had an uncertain relationship in the past. Beardsley was one of the few classical artists whose erotic work could be found on library shelves (my post-pubescent pre-internet source for both art and erotica) but like other eventual favorites of mine such as H.R. Giger and Richard Corben, I initially found the air of grotesque decadence in his work to be somewhat sinister and very intimidating.

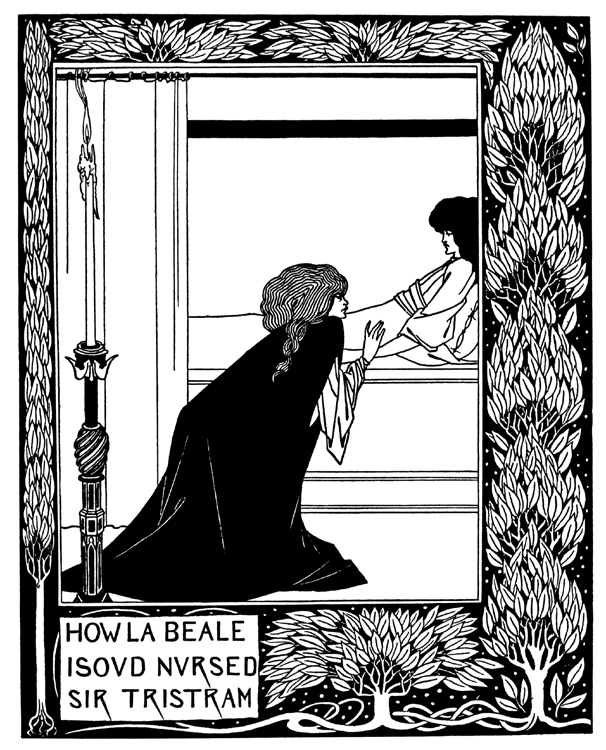

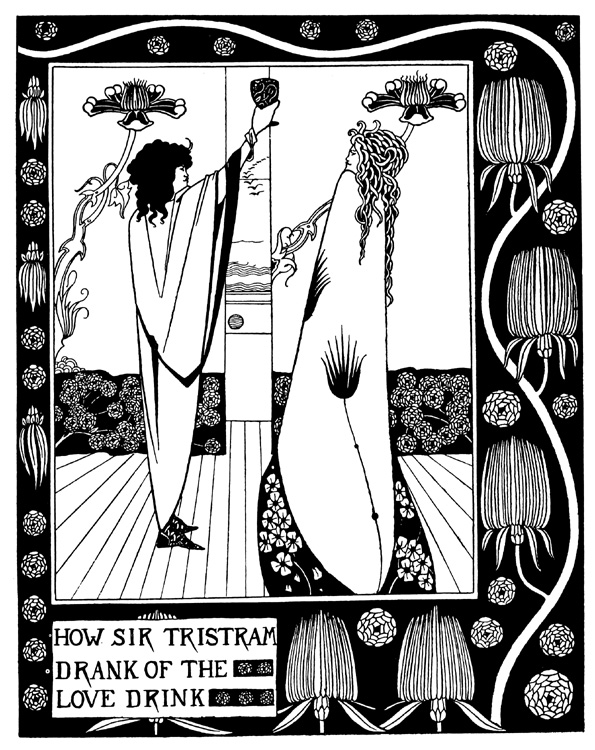

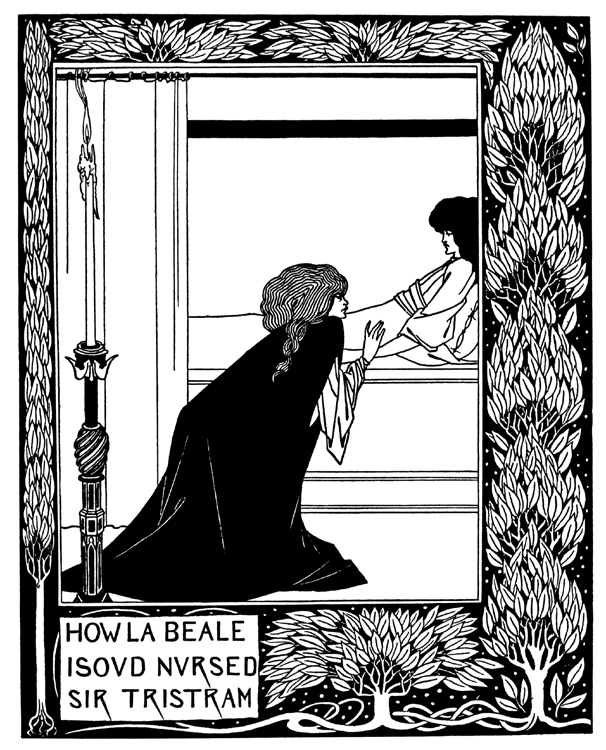

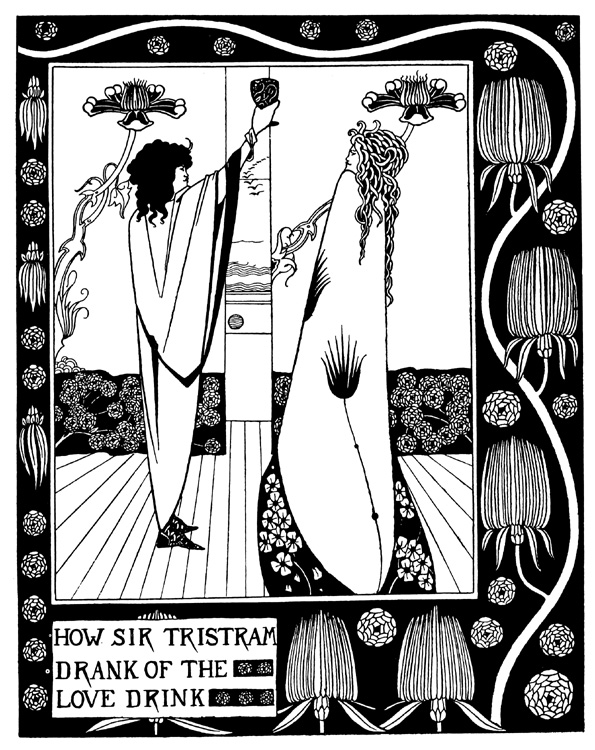

As a teenager, I had discovered the work of 19th century artists such as Edward Burne-Jones, Alphonse Mucha and Beardsley himself by way of comic book artists like Barry Windsor-Smith, Jeff Jones and the afore-mentioned P. Craig Russell. Among the Romantics and Symbolists, Beardsley was the joker in the deck. Laboring under the shadow of his Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries, his interpretation of L’Morte De Arthur had all the trappings of their chaste and higher-minded romantic fantasies but with dark-side twists that always left me both fascinated and vaguely uneasy. In Beardsley’s Arthurian tableau, the sexually-neutral androgyny that characterized Burne-Jones’ work was pushed to the level of parody. Lancelot, Guinevere, Tristram and Isolde were transformed into incestuous hermaphrodites, confronting one another in scenes suffused with a deadly languor or a decidedly unchaste almost vampiric urgency. The starkly ornamental scenes, their borders entangled in coils of spiky flowers, seemed strangely claustrophobic; voyeuristic views of chambers draped with barely-parted curtains and shadowy twilight landscapes filled with gleaming mirror/pools, trees that resemble ornamental tapers and candles that look like sex toys.

Two of Beardsley’s illustrations for L’Morte De Arthur.

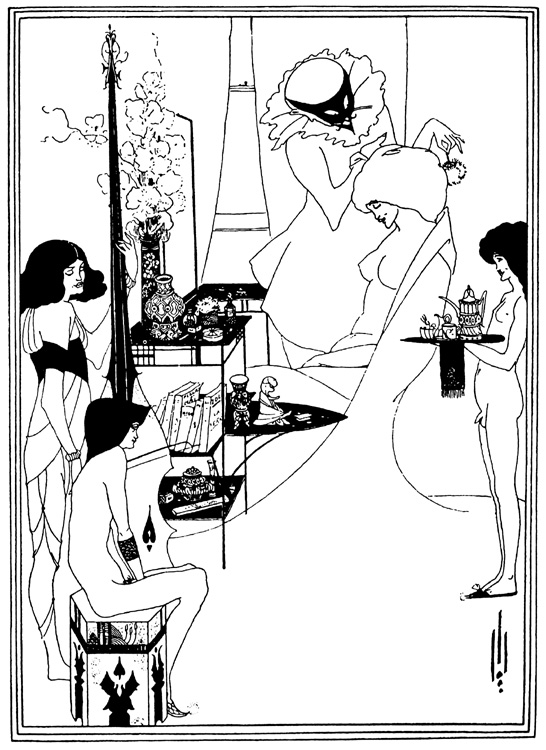

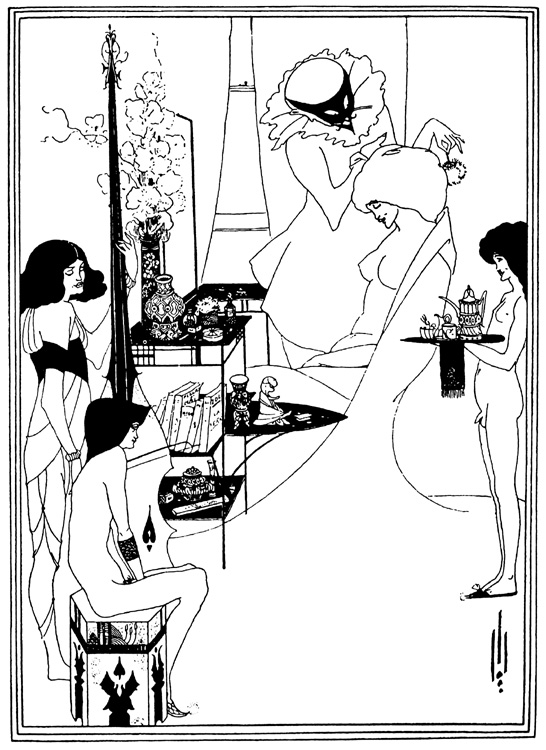

Beardsley’s Salome and the Rape of the Lock were equally daunting; lush studies in pale diaphanous textures and shimmering patterns, peopled by leering hunchbacks, gamboling fetuses and beautiful figures of indeterminate gender, their patrician faces transfixing the viewer with a cool gaze, daring them to look away from the opulent decorations and strangely distorted anatomy.

Beardley illustration from Salome

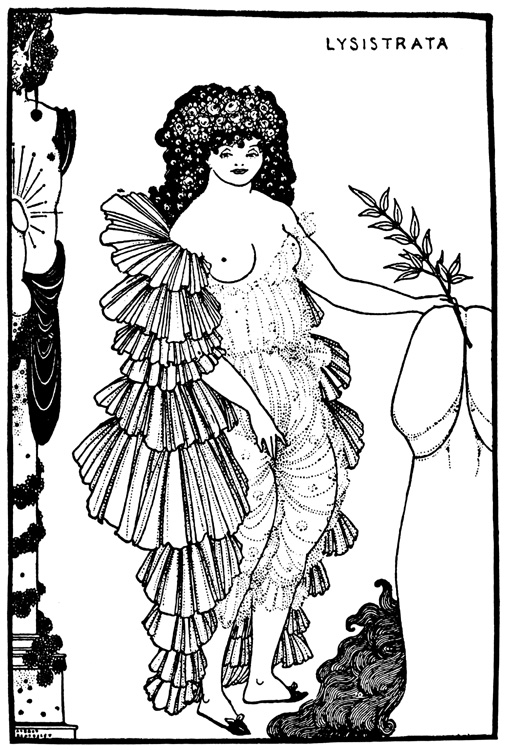

Much of the sexuality in Beardsley’s work is more implied than stated (another source of frustration for my teen-self who was usually looking for the harder stuff) but even his infamously explicit Lysistrata illustrations with their corpulent female bodies and gigantic shunga-inspired penises seemed more grotesque to me than erotic. Yet somehow, I couldn’t look away. Beneath the freakish sinister atmosphere, there was a sense of playfulness and something genuinely sexy — something I would need more life experience to truly appreciate.

Two of Beardsley’s illustrations for Lysistrata.

A significant event that brought home the true beauty of Beardsley’s work and essentially “humanized” him in my eyes was a retrospective exhibition of his work at the Fogg Museum in the mid-80’s. It was the first time I had ever seen his illustrations in their original form and I was surprised to find that the black areas which on book pages looked like the essence of pure black night were full of texture and brush strokes. In other places, the drawings had been trimmed, pasted over and whited-out. In essence, they looked like modern comic book pages. For most, this would be a minor detail but for me, Beardsley suddenly didn’t seem quite so unapproachable. He wasn’t a sinister satyr with “a face like a silver hatchet” living in a castle surrounded by grotesques; he had been a man like me, an artist/craftsman drawing illustrations to pay the rent — and if the sexuality portrayed in his work still seemed a bit ambiguous — well, I could relate to that too.

If my work and Beardsley’s can be said to have any similarities beyond the purely technical, it would probably be on the theme of the hermetic environment. Beardsley saw Tannhäuser’s subterranean Venusberg as a jumping off point for the creation of an inner world of total sexual license — an elaborate stage on which deliciously decadent fantasies, repressed by the society of his day, could be played out without regard to social order or gender, safe within the womb of the Goddess.

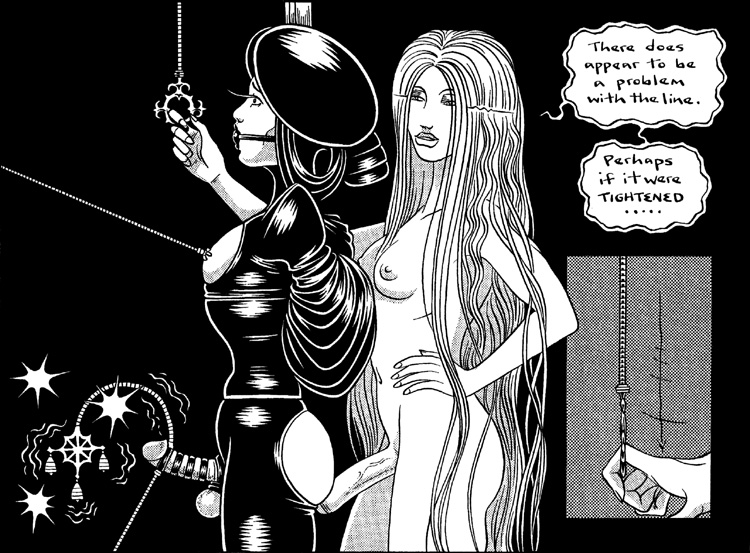

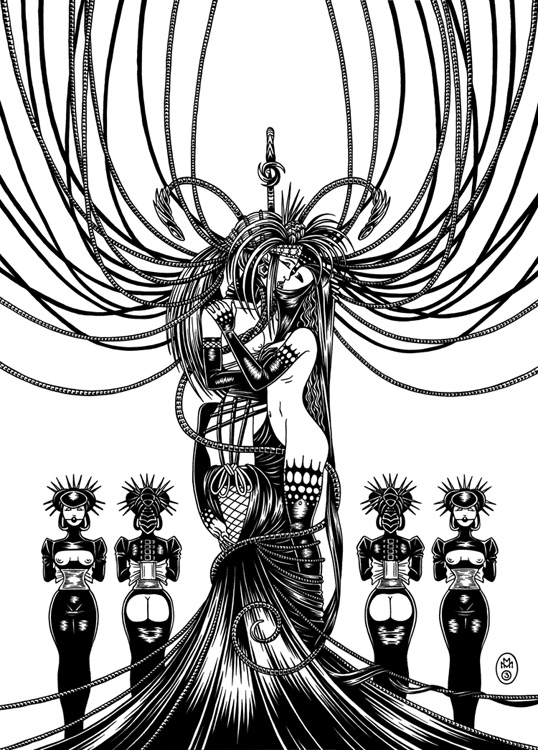

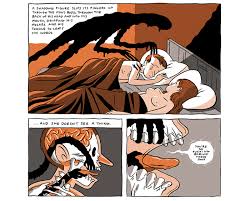

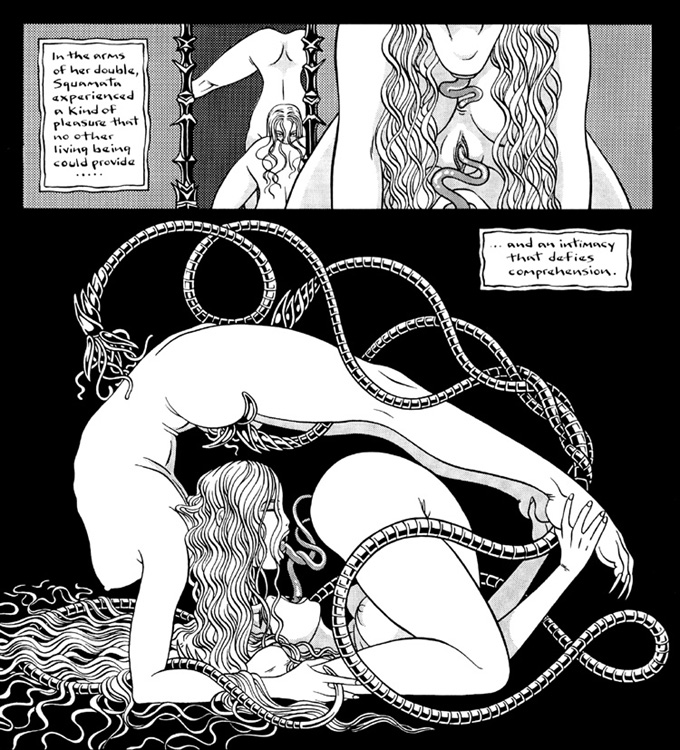

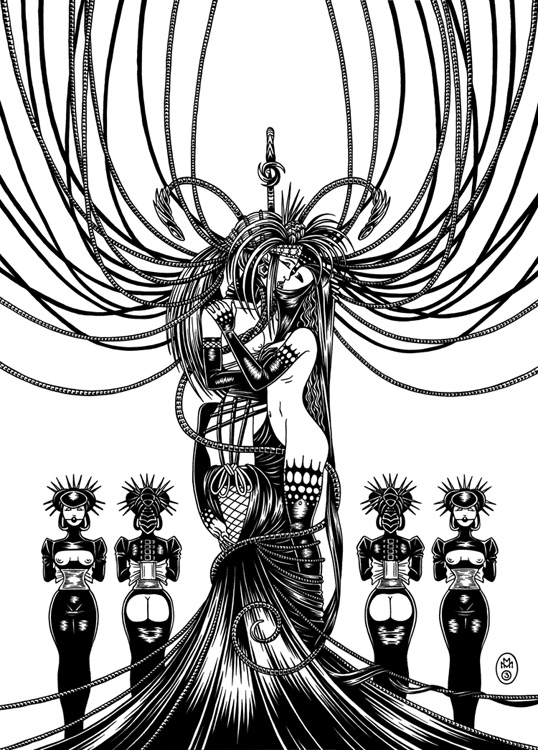

From In a Metal Web II, ©Michael Manning

Shaalis the Sacred Androgyne is my Venus, “S/He who delights in that part common to both Hir men and Hir women”, the Goddess incarnate with both cock and cunt who accepts the intimate worship of Hir slaves (beautiful men and women made equal by gender transformation) while dispensing Hir sacrament through blood ritual and sodomy. I took narcissism and the mirror, two other recurrent themes in Beardsley’s work, to an incestuous extreme with Shaalis’ former lover, Squamata Serpentine. She and her sister Lichurna are the ultimate fantasy/cautionary tale of falling in love with your own image.

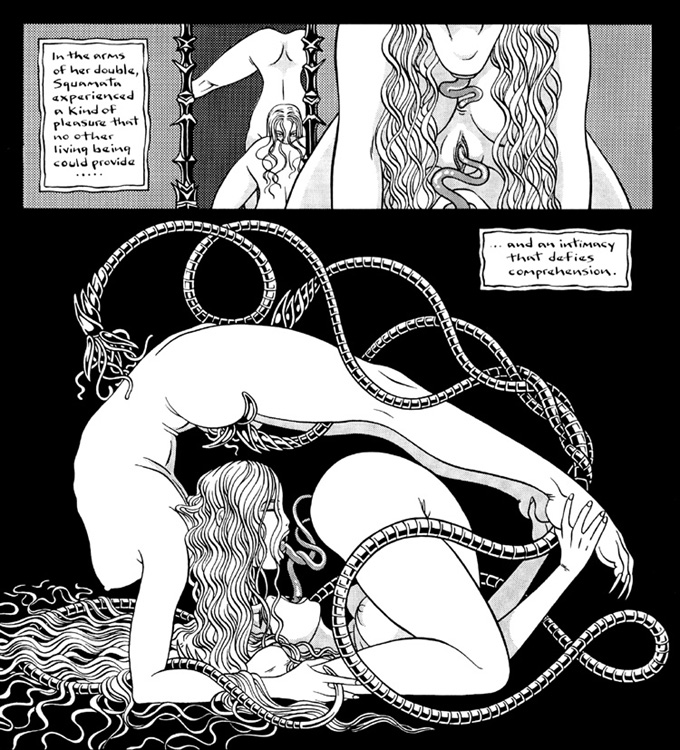

From In a Metal Web II, ©Michael Manning.

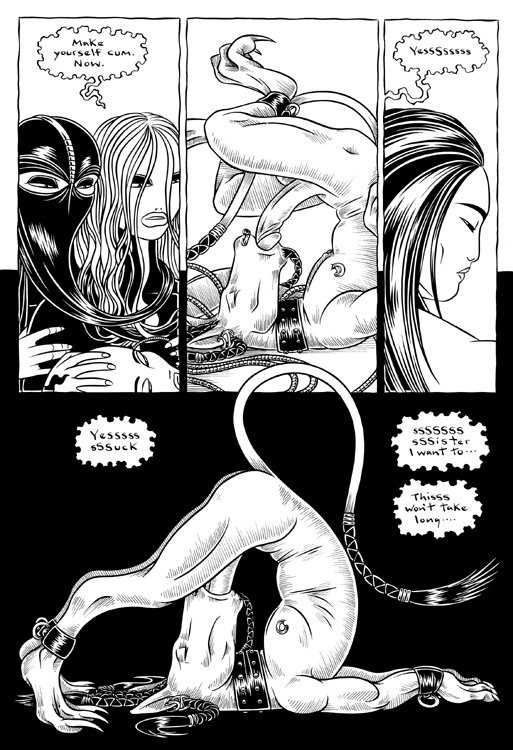

Theirs is a truly hermetic existence, a divided soul locked in a self-devouring embrace while their sex-starved Tengu slave Gion is reduced to sucking himself off for their pleasure. I wasn’t fully conscious of it at the time I first started drawing them (there are versions of Shaalis and Squamata that date back to my high school days) but now when I look at the Sister’s snaky locks and contortions and Shaalis’ regal perversity, I can’t help but see echoes of Beardsley’s Athenian bacchantes from Lysistrata and L’Morte De Arthur‘s witchy androgynes.

From Hydrophidian, ©Michael Manning.

I realize that the way I’m describing my own work here may sound as off-putting to some as Beardsley’s work initially was to me. One person’s utopia, especially one founded on exploring the limits of carnal desire, can easily seem like another’s person’s dystopia, misinterpretation being one of the many risks we run when we choose to share our dreams with others. Just as the Garden itself is a mirror for the inner workings of the mind of it’s multi-gendered ruler, I suppose the series as a whole could be thought of as a reflection of my own imperfect yearning for a polysexual utopia that real-life sex parties and BD/SM play can tantalizingly approximate but never quite fully achieve. Whether the Spider Garden and the Venusberg can be an ideal to anyone other than myself, Aubrey Beardsley and the characters that live there is ultimately another matter of personal choice. For some, they may just be rest-stops on the way to worlds that none of us has even imagined yet.

Print of Shaalis and Squamata, ©Michael Manning.

©2008 Michael Manning

Excerpt from “The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser or Under The Hill” © Aubrey Beardsley