Li Kunwu and Philippe Ôtié’s A Chinese Life is the kind of book I would normally resist reading; the chief reason being it’s overly familiar subject matter.

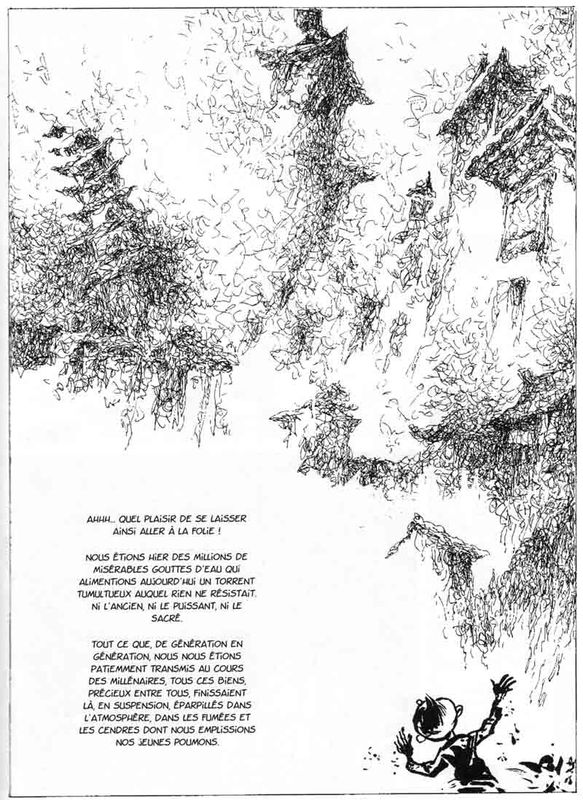

For a period during the 80-90s, it seemed almost impossible to escape the Cultural Revolution Industry. These were the scar dramas which followed in the footsteps of the scar literature; the subject de jour once Deng Xiaoping pronounced that period between 1966 to 1976 as being “ten years of catastrophe” (shinian haojie). As far as the Western sphere is concerned, one should not underestimate the effect the commercial success of works like Jung Chang’s Wild Swans had on this era. For Chinese writers and filmmakers who had stories to tell and willing publishers and financiers, the Cultural Revolution soon became ten years ripe for cultural monetization.

As far as Chinese contemporary art is concerned, a collector once laughingly told me that Chinese artists had discovered that the key to financial success was to make art which is “political.” Not an approach alien to the professional writer who understands full well that controversy sells, but here made more acute by the Western preoccupation with China’s political woes almost to the exclusion of all else (anyone read any non-political Chinese literature lately?).

The 2012 Nobel Literature prize winner, Mo Yan, presents us with the opposite side of the coin. The disgust with which some Western-based China watchers and dissidents greeted his elevation to the ranks of the literary “elite” was largely based on his poor politics and only secondarily his lack of literary merit. In short, he is perceived in some parts to be a party boot licker or at best a literary coward without a strong inclination to be exiled and imprisoned like a latter day Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn or, more precisely, the Nobel Peace laureate, Liu Xiaobo. Mo Yan’s novels are in fact frequently political but not in the way favored by Western journalists and academics. He is, in fact, the wrong kind of Chinese novelist.

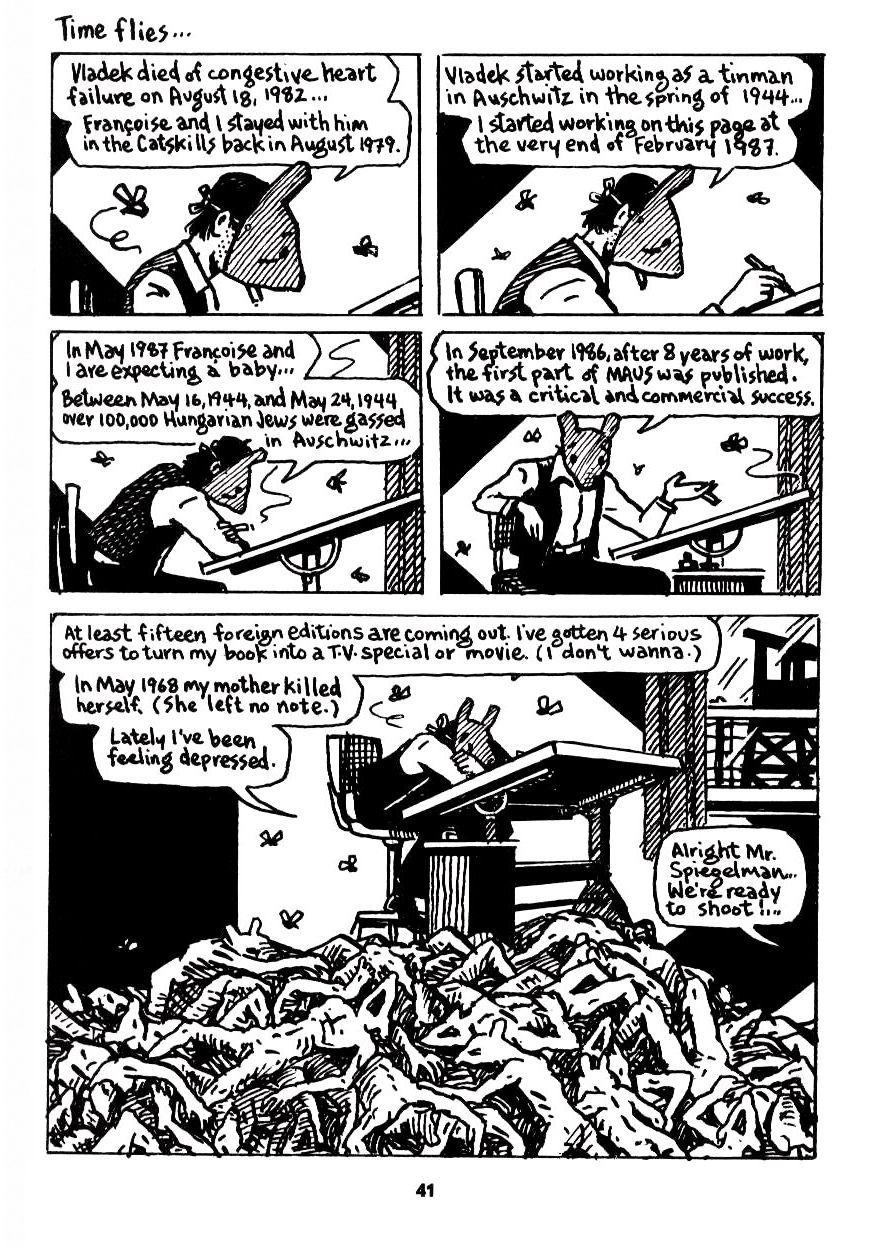

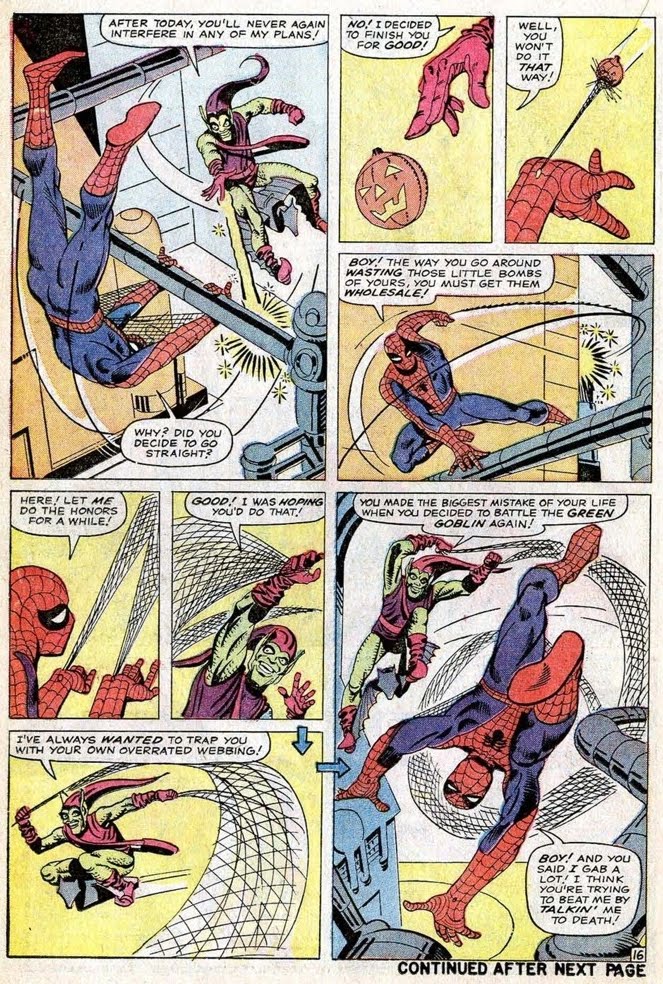

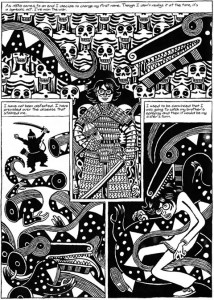

A Chinese Life is a bit late to the party and passed with minimal notice in the year of its publication. Its contents would appear to be of a piece with the literature and movies which have inundated the West since the opening of the Chinese market. As a comic, it is solidly mediocre, the kind of “worthy” book some would point to if questioned concerning the suitability of comics for adults. It does gain some gravitas from its roots in autobiography but, as always, the failure here lies in the lack of narrative imagination and literary beauty—as history, it is far too shallow; as a work of literature, plodding and unemotive. It was, in short, an absolute chore to get through and ranks as one of the worst things I’ve encountered concerning China’s late 20th century history. The fault lies largely with Ôtié who fails to sculpt Li’s story into an engaging whole. All that remains is Li’s frequently interesting draftsmanship; he is a good artist undone by a poor storyteller.

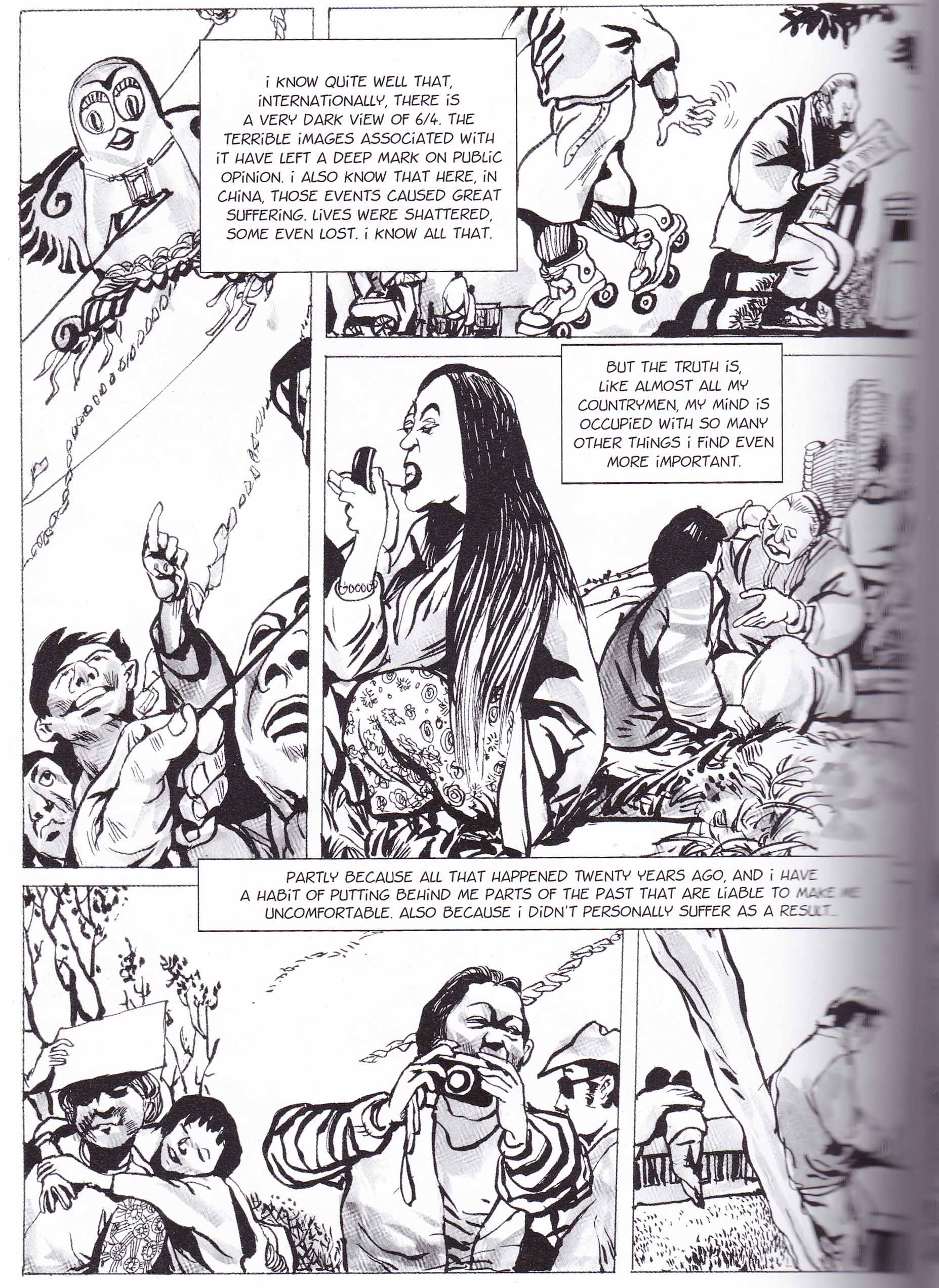

If a reviewer like Rob Clough is made to wonder whether A Chinese Life is propaganda, it is simply the result of the largely unexamined and uninterrogated life which fills these pages—an approach which informs not only the third and final book of A Chinese Life (the one concerning modern China) but, for all intents and purposes, its entire length. If there is one exception to this rule, it would be Li’s thoughts on the “6/4” incident.

So what made me borrow and read this book? Well, it was this snippet from a review by Rob Clough:

“The whole philosophy of the book is very much “the past is the past”…we once again go back to the Deng doctrine of “Development is our first priority”. As Li describes it, it’s the only priority.

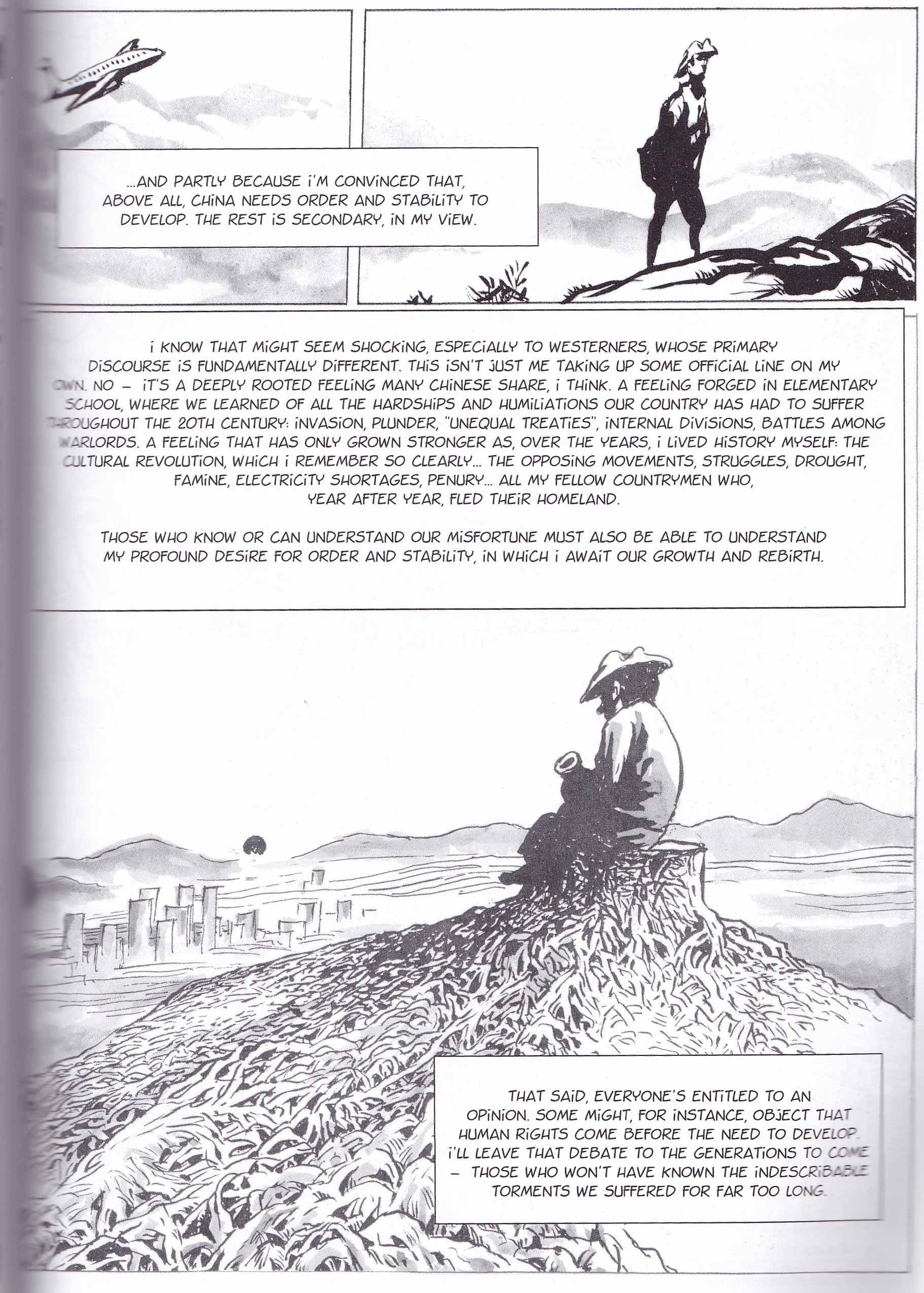

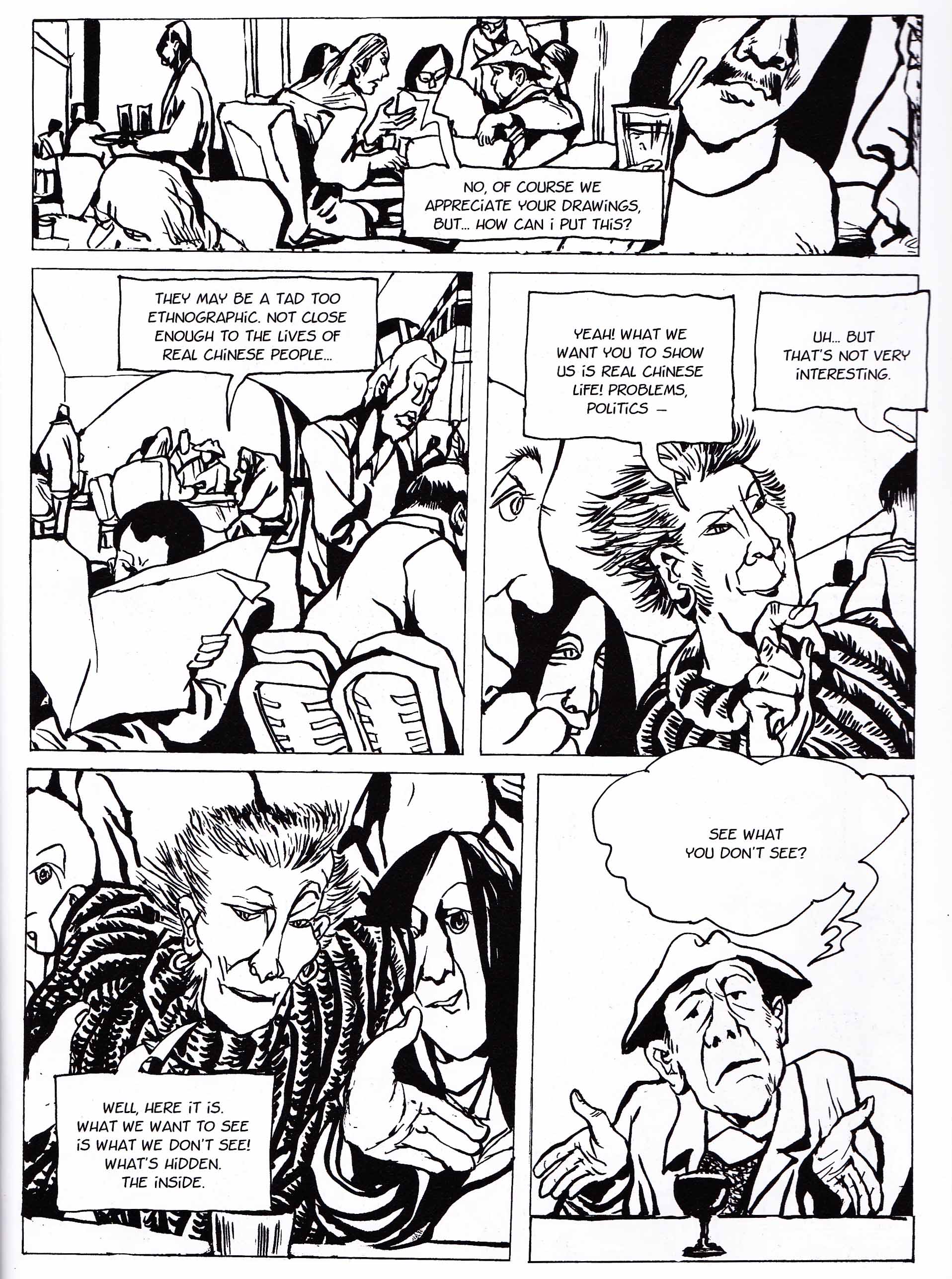

This leads to an interstitial scene where Li and Otie argue about how best to present his view on the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. Otie stresses to him the importance of this event to Western readers, and Li is resistant, because he said that he wasn’t anywhere near Beijing, only listened to the reports on the radio and has no idea what actually happened. Because he “didn’t personally suffer”, it wasn’t something that was really part of his story like the Cultural Revolution, Great Leap Forward…He notes that while he understands that lives were lost and people suffered, he considered the event within the context of Chinese history. Essentially, he was tired of China being a whipping boy for foreign interests and invaders. He was tired of instability. He was tired of being behind the industrialized nations of the world. The most salient quote is “China needs order and stability. The rest is secondary.” The past is the past. Development is the first priority.

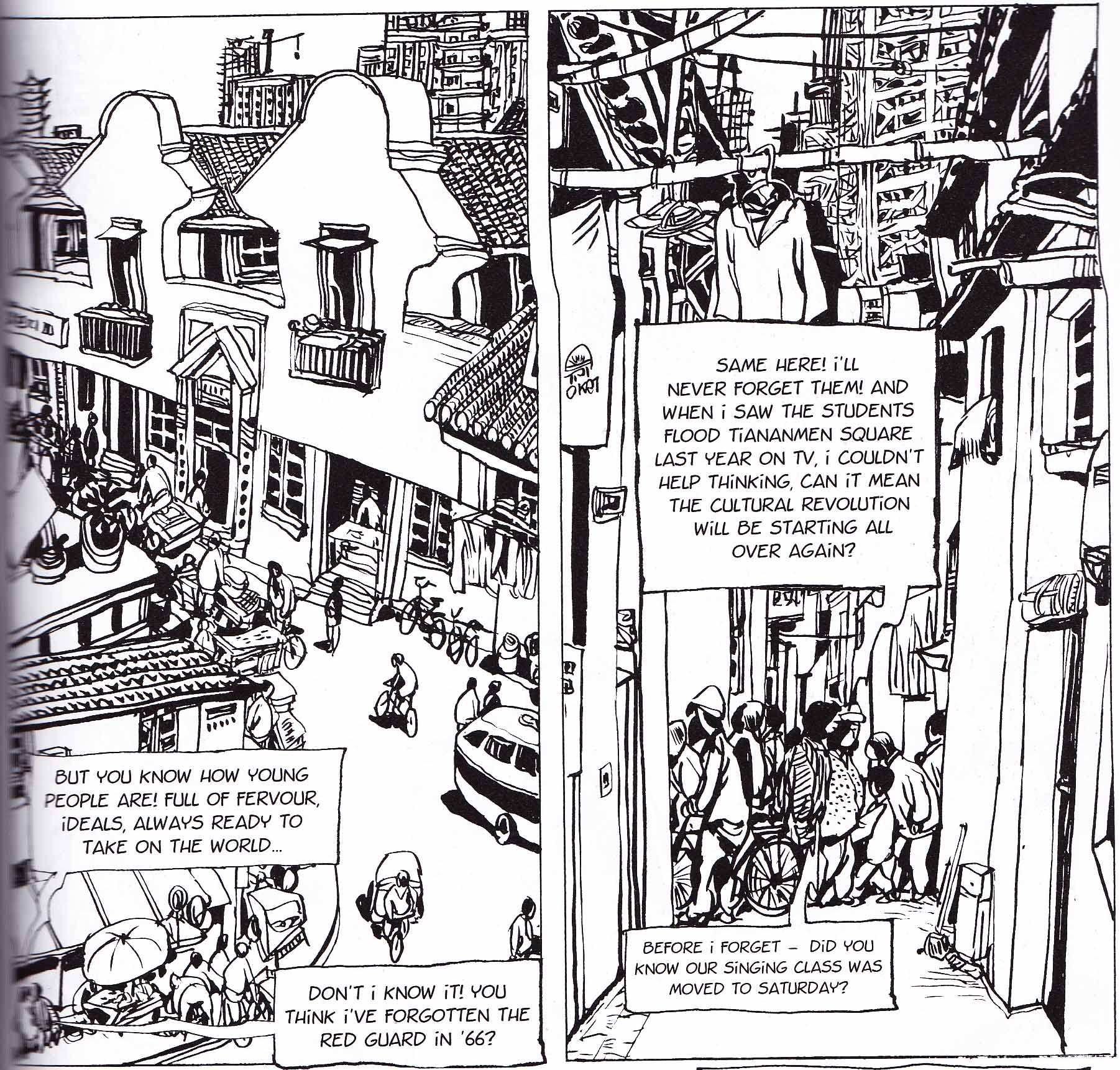

It’s a statement that makes a degree of sense within the context of a countryman who suffered during the prior youth revolution (indeed, some women in his story fear the events of the protests as the potential return of the Red Guard)…It is disappointing, however, to see an intelligent man like Li who fancies himself a moralist in rooting out corruption to simply toss aside human rights and freedoms as expendable when the corporate well-being of China is involved. It is a kind of moral compartmentalization that reeks of hypocrisy, the same kind of hypocrisy he faced (and was part of) during the Cultural Revolution. It values dogma (or progress) over humanity.” [emphasis mine]

But what exactly does a word like a “progress” mean to a person like Li? His words are sparse, his actual intentions up for conjecture. When Li indicates that, “China needs order and stability. The rest is secondary,” should we take his words as those of a coward, a hypocrite, or one with little respect for “humanity?” Can there in fact be any conception of human rights in a state without order and stability?

What can it mean for a man like Li to hear of distant reports of protesters being killed when the reports in earlier times had been those of war and cannibalism; the evidence before his eyes that of people dropping like flies by the wayside. The past clearly isn’t the past for Chinese citizens like Li. If anything, it thoroughly colors their perception of China’s present day fortunes.

Two other reviews online arrive at the same point as Clough in the course of their largely positive reviews:

“Li is far more a witness than a commentator. He declines to cover the events of Tiananmen Square because, he says, he wasn’t even there (but that scene with his co-writer Philippe Ôtié shows him wriggling apologetically to avoid it – it was obviously a bone of contention), and you won’t see Tibet mentioned once. He’s far prouder of what China has accomplished in thirty-five short years…” Stephen at Page 45

“Although this 60 year story largely ignores China’s fragile relationship with Taiwan and Tibet and only briefly mentions Tiananmen square, Li acknowledges these weaknesses by openly accepting that this is a story of his life, a single man, and no single man lives through all the history of his entire country (he didn’t know anyone affected by Tiananmen and therefore had little to say).” Hardly Written

The reviews which accompanied the publication of A Chinese Life seem more useful in revealing the differing attitudes of readers (presumably) from the West and the mainland Chinese; for Li’s attitude towards the Tiananmen demonstrations are hardly novel and have been ennunciated periodically over the years by the Chinese people. On the other hand, it is all too clear that the Tiananmen Massacre is one of the central prisms through which the West understands China, in much the same way the word “Africa” conjures up images of war, famine, and disease for the casual reader.

These reviewers would appear to be readers who have grown up in stable and ordered societies while Li has actually been one of those deluded and disappointed revolutionaries; one who has been recurrently attracted to mass movements. These experiences have clearly allowed him to entertain doubts concerning received notions of what is best for China and what human beings need first and foremost. And in this instance at least, ideology has come in second best.

Progress and human rights may not be mutually exclusive but it seems obvious that Li views the democracy movement and potential revolution of June Fourth as detrimental to the former and, as a consequence, to the latter. The prescription which America has recommended and administered to its client states has been political freedom (this word used loosely) before economic freedom, while Li clearly believes that the reverse is the surer course towards true liberty—patiently awaiting the creation of an educated middle class more attuned to the demands of a democratic system and who will, hopefully, make greater demands for political expression. Such has been the course for the former dictatorships in South Korea and Taiwan as well as the authoritarian democracy of Singapore.

What is the objective of political freedom if not the happiness of its people? For many Chinese today, mere sustenance, attaining a first world lifestyle (for all its ills), and the well being of their family members come before notions of a democratically elected government, especially when that tarnished model of democracy, the United States government seems effectively little better than the authoritarian one they are currently experiencing. The rampant capitalism which is America’s true essence, on the other hand, seems rather worth emulating; greed being altogether more attractive as far as human nature is concerned. Liu Xiaobo is a poor thinker when it comes to the history of the Western powers but he affords a somewhat different perspective when it comes to China’s economic “rise”:

“The main beneficiaries of the miracle have been the power elite; the benefits for ordinary people are more like the leftovers at a banquet table. The regime stresses a “right to survival” as the most important of human rights, but the purpose of this…is to serve the financial interest of the power elite and the political stability of the regime… […]…an autocratic regime has hijacked the minds of the Chinese populace and has channeled its patriotic sentiments into a nationalistic craze this is producing a widespread blindness, loss of reason, and obliteration of universal values…The result is our people are infatuated more and more with fabricated myths: they look only at the prosperous side of China’s rise, not at the side where destitution and deterioration are visible…” [emphasis mine]

A recent survey by researchers at the University of Michigan indicates that China’s Gini coefficient for income inequality could be as high as 0.55 having recently surpassed that of the United States. According to a report from Peking University, China’s Gini coefficient for wealth inequality comes in at 0.73 which is slightly lower than that of the U.S.. If there are lessons being learnt from the West, it would appear to be all the wrong ones. Consider the words of Liu Xiaobo in “On Living with Dignity in China” and see if they might not also be applied to the America we all know and love:

“In a totalitarian state, the purpose of politics is power and power alone. The “nation” and its peoples are mentioned only to give an air of legitimacy to the application of power. The people accept this devalued existence, asking only to live from day to day…This has remained a constant for the Chinese, duped in the past by Communist hyperbole; and bribed in the present with promises of peace and prosperity. All along they have subsisted in an inhuman wasteland.”

[I should note here that the 2013 BBC Country Rating Poll suggests that the citizens of China and the United States have equal amounts of antipathy towards each other.]

Given a choice between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama, the American public chose the lesser evil—the man who has delivered some change and only marginally more murder—the man with no moral center. It is not hard to see that Li might view his own choice in a similar light. And he is living with his choices as are the rest of the Chinese people. As I sit in the comfort of my home, in all my life not having suffered one day of hunger, repression, and fear as severe as those experienced by Li Kunwu through China’s turbulent 20th century, I am inclined to be more understanding and less judgmental.