Dear Giant Squid,

What do you think of the Gay Utopia?

Signed,

Noah Berlatsky

Dearest Noah,

Great and Terrible Gods, it has been ages uncounted since I last thought upon the Gay Utopia, my time in it, and my subsequent reflections as to why the Gay Utopia was not long for this world — and, just to forfend the all-too-common assumptions, it was none of the maws of the triple-headed hydra of disease, drugs, and dilettantish dandyism that ultimately devoured the pure and vital guts of the Gay Utopia, leaving the husk that so besmirches today’s cultural landscape.

Let it suffice to say — despite having the sounding of the besouréd grapes — I like not the Gay Utopia at present.

To explain: The year was ninety-seventy and five, and I found myself in a rented panel truck, touring the small musical venues of the American Middle West in the company of Lütz Günther, Brad Zywicki, and Kirk Dindorf — each natives of Milwaukee — as drummer and road manager to our glamorous disco rock quartet, the Gay Utopia. (The name taken, I presumed, from Sir Francis Bacon’s lesser known alchemical sequel to Novus Atlantis, Utopia Hilaris.)

We three were, afore the formation of the Gay Utopia, perfect strangers. Brad was a student of the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, whilst Kirk found employ changing of the oils automotive. I had, just prior, gone to the crossroads at midnight, had met with the Devil, John Bonham, and three engineers from Pearl Drums, had signed papers in triplicate, and the final result had been metronomic-steady timing, a preternatural “feel for the groove”, and a lead-crystal bell of enormous girth, beneath which were shrouded from the water’s smothering embrace a perfectly balanced, self-tuning, birch-and-maple shelled drum kit with three snares, six tomtoms, double bass drums with double pedals each, 14 variegated cymbals, a gong, and 18 independent microphones, each with the finest Mogami electronics throughout. The effect was really quite stunning.

We happy few were among the three-quarter dozen respondents to a classified advertisement placed by Lütz Günther, seeking a backing band to aid in the performance of his powerful, histrionic ballads.

Nightly we made our camp in the parking lots of Fond du Lac, Green Bay, Appleton, and similar environs, extended the riser from the back of our truck, then strutted and fretted our hour upon the stage, full of sound and fury, bespangled and glittered, sheathed in lamé, lycra, and leather. As I riffled and rolled across my skins, Kirk and Brad wove powerful, ascendant, interlocking melodies and harmonies upon the bass-guitar and guitar-guitar, respectively, whilst Lütz thrust, gyrated, moaned and ecstatically cried out, thews a-rippling, his beribbonéd tambourine gripped in his muscular human-paw.

In the twilight of early morn, after the final pink and slick guppies had retreated to their parental domiciles, I meditated long upon the alchemical progress of your forefathers, whilst Lütz, Kirk, and Brad retired to their motel’s room, presumably to further discuss the writings of Sir Francis Bacon and his cohort.

It was but a few weeks afore we were playing large shows of the stadium, our adoring fans batting at beach balls, igniting lighters, donning facial makeup, and consuming vast bong hits and mountainous drifts of cocaine within vans that were a-rocking, thus precluding the knocking. It was a glorious time, and our messages — including “Mr. Sparks and his Rusty Trombone,” “A-Tisket, A-Tasket, A Chicken for Me Basket” and “Frottage in the Cottage” — were broadcast far and wide across the land.

Many suffer under delusions as to what it was to be in the Gay Utopia. Did we rock and roll all night and party every day? No. We rocked or rolled Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, discoed Saturday and Tuesday, rested beneath Thursday, and played a series of unsuccessful tent revivals on Sunday, until late 1977, when we simply gave Sunday over to additional light instrumental discoing, to permit Lütz to nurse his hangovers in the solitude of his enormous, spherical, catamite-choked satin bed. These Sundays, in most regards, were the worst of days: Both Kirk and Brad sorely missed their families, and also, lacking the unifying distraction of Lütz instruction and pompery, were at each others throats, bickering with equal vitriol over matters philosophical, political, and musical.

There was, for example, much haranguing and consternation about whether Christian Rozenkreutz was in fact an actual gentleman of history, or merely a metaphor for half an alchemical equation. There was also much dispute on the lineage of Mr. Francis Bacon and his descent or lack thereof from the great Roger.

Did you practice of the free love, irregardless of the gender or identity of the anatomy to which — or via which — that love was applied? Hardly; this was the Gay Utopia, I remind you, and not the Rolling Stones or Simon’s Gar Funkel. We were, first and foremost, consummate professionals concerned primarily with the quality and duration of our craft, and its intersection both philosophical and historical with the great Magico-Religious currents of Western Religious and Political Thought. Almost every waking moment not spent performing or consuming comestibles was dedicated to practice, honing skills upon our instruments of choice, and the invention and refinement of new compositions — there was hardly world enough and time for sexual gratification at all, let alone sufficient masses of such acts to allow it to become both impersonally casual and take hold as our defining feature. As I recall, when love was to be had, it was priced reasonably, and at a per-project rate. Such appointments were largely kept by Lütz, who had a certain passion for public service. As I recall, gratuities were also accepted.

Do you guys do it in, like, public bathrooms and locker rooms and shit? No. It is rare indeed to find a public bathroom or athletic changing room that is, first, private, and second, possessed of suitable electrical wiring to support the load created by our sound board, amplification systems, foggers, and colored lights. Additionally, it is beyond conception that such a public rest facility exists with enough unoccupied space to accommodate my salt-water tank and drum kit. Finally, Lütz complained that the acoustics of most bathrooms were “confusing”, making it devilish to attempt to stay upon the key.

Ultimately, the Gay Utopia dissolved along lines almost stereotypical: There was a falling out over several inconsequential matters — my desire to explore non-integer time signatures compliant with the higher principles of John Dee’s treatise upon the cosmological and alchemical monad, Lütz’ desire that I return the $370,000 embezzled from the band’s coffers (“borrowed” as I have stressed, with the intent of immediate restoration, had not my studies on the transmutation of base matter gone tragically awry), and Brad’s and Kirk’s need to leave the limelight — disputes destructive to the bands’ ongoing cohesiveness. Also, Brad was always somewhat of the chubby, on which point Lütz often harangued, as it was deleterious to the band’s “fuck appeal, ’cause no kid is gonna cream his jeans watching Brad’s fucking titties flop around while he noodles over flatted-fucking fifths!”

Some say the diabolus in musica is the diminished fifth tritone, but I know that it is truly Lütz Günther.

Subsequent to the pecuniary dispute, I was asked to leave the Gay Utopia, and Brad and Kirk soon followed, choosing instead to raise alpacas in rural Wisconsin. Perhaps they there formed their own gay utopia; we drifted out-of-the-touch, and I never thought to ask if the alpacas were of mixed gender afore our drift became so wide as to span a breadth incommunicable.

Ghoulishly, despite having aborted its melodic soul and discarded its own percussive heart, the Gay Utopia lived on, undying. Lütz held of the auditions, and restocked his stage, manning his guitar-guitar and bass guitars with a revolving cast of pouting, tin-eared young miscreants. The drums were first quasi-competently staffed by an octopus, then later — and in a degraded performance — by three marmots in diminutive self-contained underwater breathing apparati, then by two-dozen oysters, and finally a series of interchangeable boys in eye-liner, each more insouciant than the last.

These words, too, are nought of the soured grapes, but rather simple observations, searingly accurate, of the tight-bunnéd, six-packéd, tone-deaf man-children Lütz favored over legitimate musicians and managerial staff.

In the interregnum Lütz partnered and disenpartnered — saved the indignity of serial marriage and divorce by local statute — at least a half-dozen times, reconstituting the Gay Utopia at least as often. Despite the limping, carnival freakshow still performing under that name on the many, disused third-stages scattered across the great and undifferentiated middle of this nation, in most any sense of the notion, the Gay Utopia exists no more.

Lütz, it should suffice to say, is something of a crippled man — first, in that he has a dearth of sustainable emotional depth, and second, in that his lower extremities were crushed during a partial stage collapse in a shopping mall in 1992 (see “Gay Utopia Rocks Cleveland— Larger Tragedy Averted” in the Cleveland Plaincothes Dealings). And I, while clearly a great and terrible success story in this day, had many rags leading to these current riches, and more than a few of them torn asunder by the ignominy I inherited from my quick exeunt from the Gay Utopia. In truth, it is only Brad and Kirk who have unquestionably thrived not simply despite the Gay Utopia, but owing to it.

I see them often in my day-the-dreams: embracing each other, wrapped in supple blankets of the finest alpaca wool, their cheeks and shoulders pink against the golden fleece that surrounds them and keeps them enwarmed against the winter’s icy wrath. Love of that sort is the true transmutation from material to numinous; had Sir Francis known of such a gay utopia, he would have quit his philtres and phials and lived a ripe age. Of that last, one can be certain.

In conclusion, we see that, even when a question seems simple and its answer direct, within is oft enshrouded a most attractive mystery.

Still I Remain,

Your Giant Squid

Semper Fidelis Utopia Hilaris

____

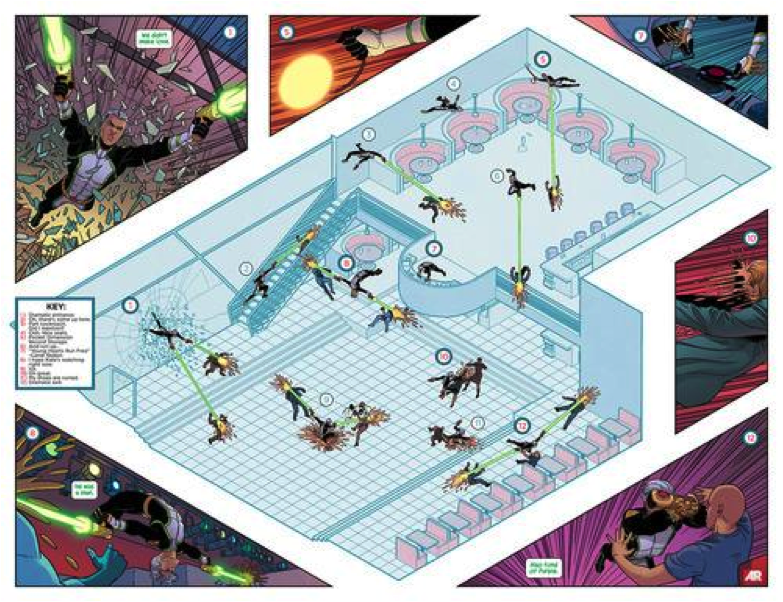

This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007. A map of the Gay Utopia is here.