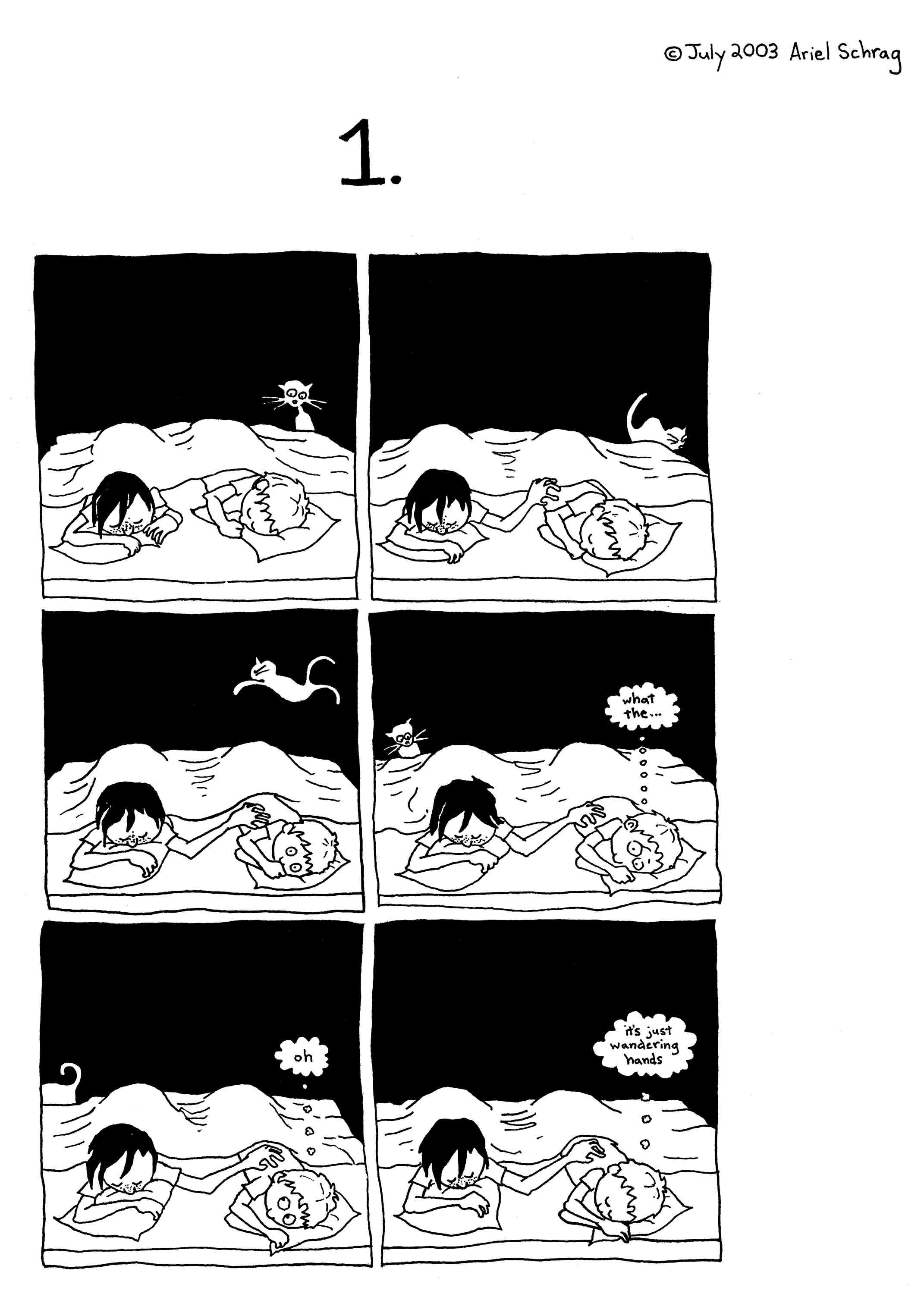

This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007 . A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

_______

Yearly Archives: 2014

Utilitarian Review 3/29/14

On HU

Featured Archive Post: Betsy Phillips on Iron Man the song and the superhero.

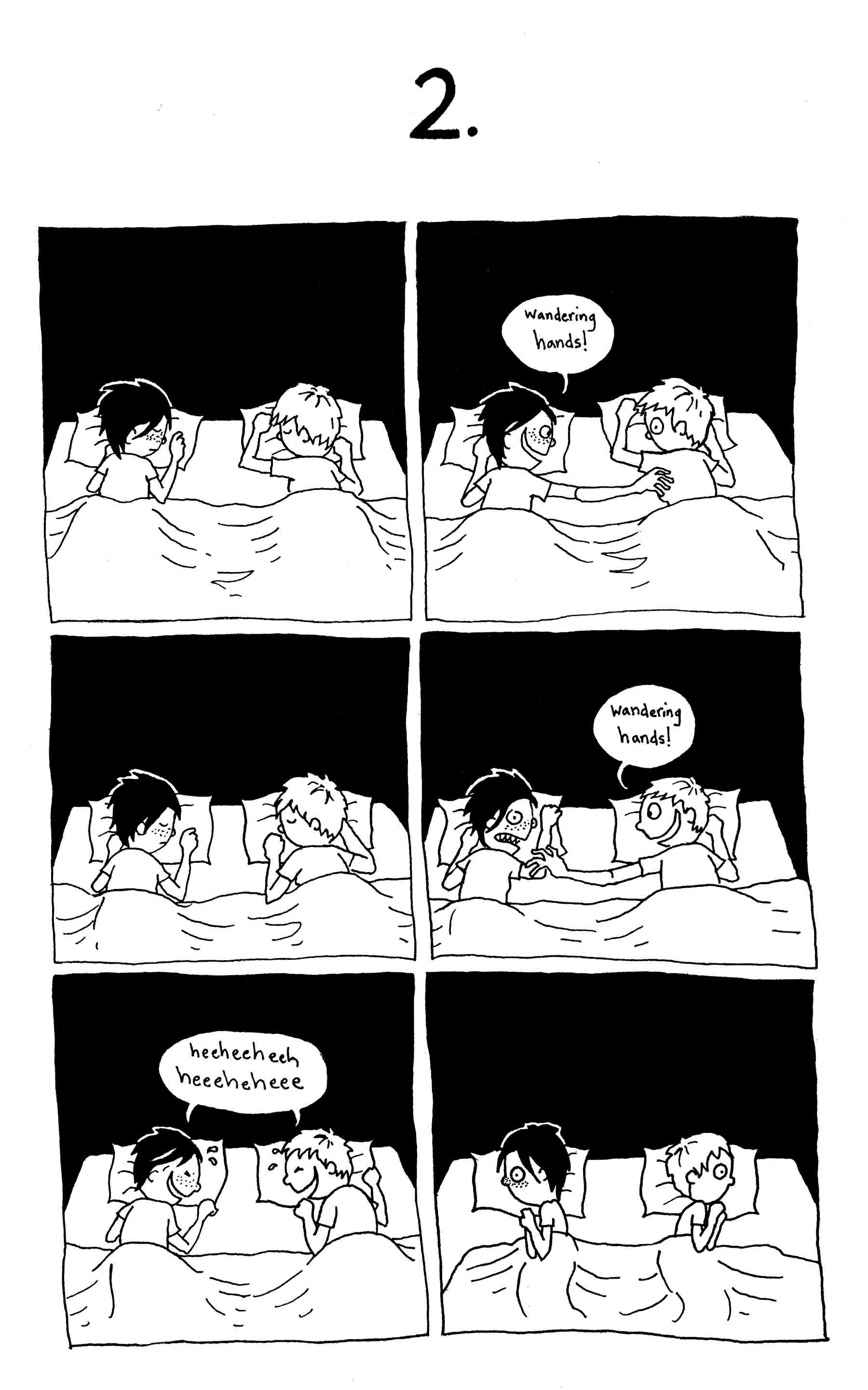

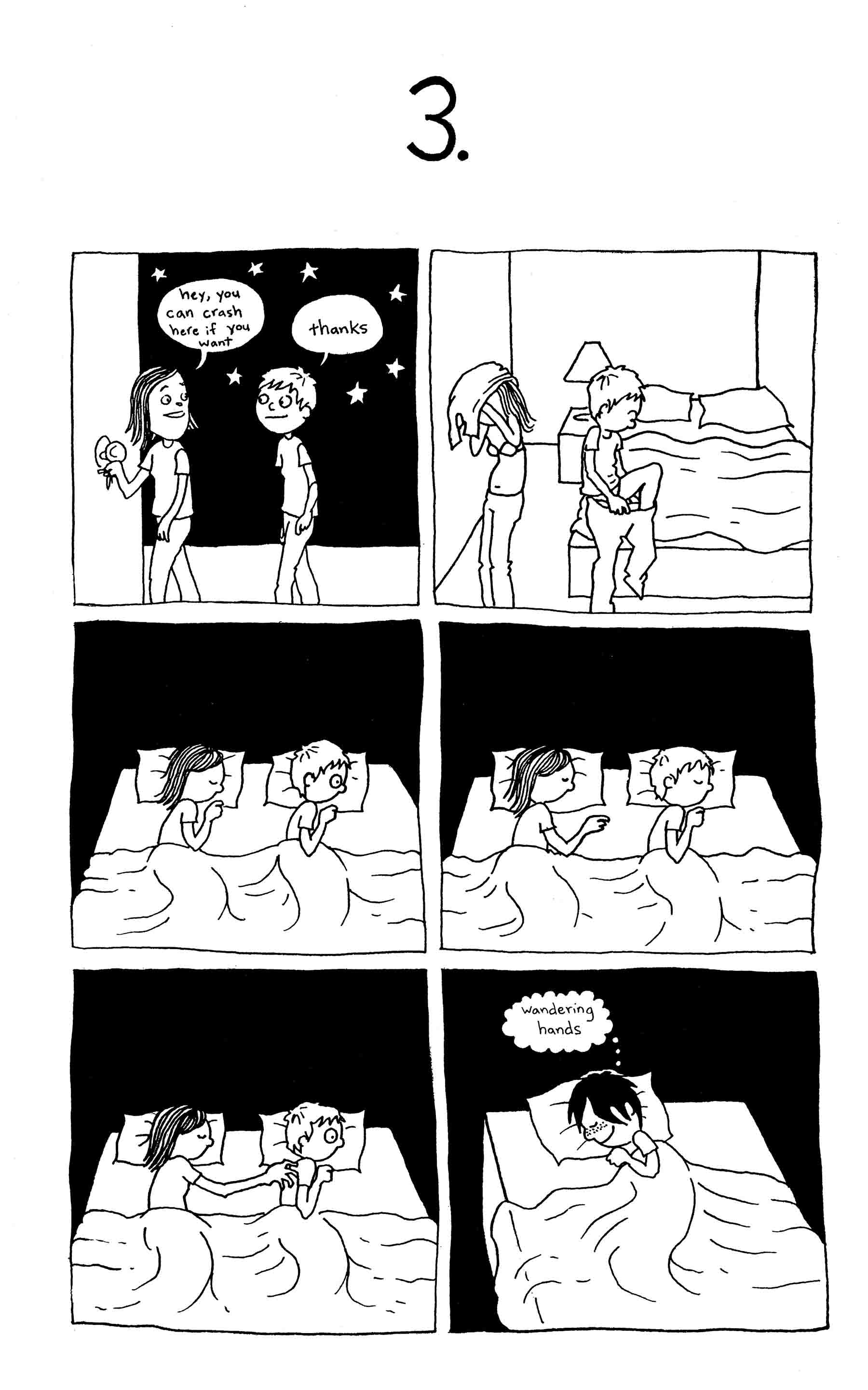

Lee Relvas‘s lovely vision of the gay utopia.

We all chatted about the most overrated television show (and possibly most underrated if such things exist.

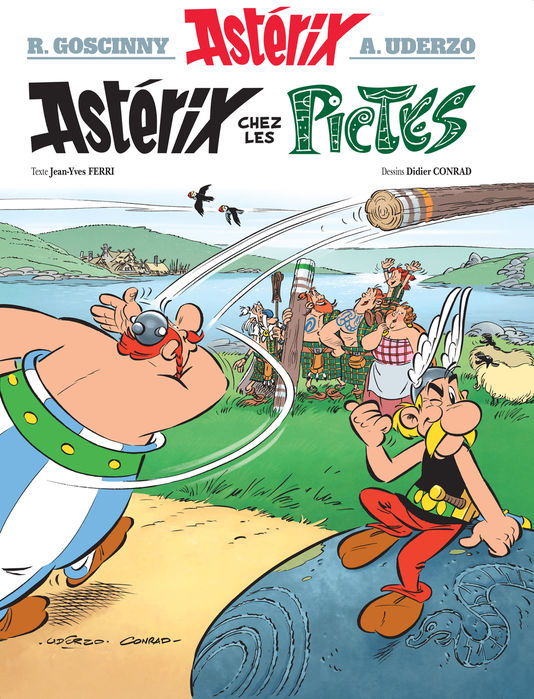

Alex Buchet on the mediocrity of the recent Asterix legacy volume (Asterix and the Picts).

Chris Gavaler on the sources of Sandman.

I ask if this post needs a trigger warning.

Adrielle Mitchell on comics and walking (for PPP.)

Kailyn Kent on wine at the Grand Budapest Hotel.

Utilitarians Everywhere

At the Atlantic I wrote about:

—the self-conscious incoherence of Divergent

— the 4 ways sci-fi handles race

—I wrote about the bracingly cynical Schwarzenegger cop drama Sabotage

At Splice Today I wrote about:

— how Ginsburg and Breyer should retire

— student debt as nightmare dystopia in the comic The Default Trigger

And I worked on this study guide for Orson Scott Card’s Speaker for the Dead

Other Links

Julianne Ross asks why all action heroines are petite.

Hoping I get to see Dear White People at some point.

The debut issue of the journal Porn Studies is online.

Erin Gloria Ryan on CancelColbert; Brittney Cooper on the same.

Russ Smith tells alt weeklies to go out with some dignity, for pity’s sake.

The Grand Budapest Hotel’s Lost Pouilly-Jouvet

“Do it—and bring a bottle of the Pouilly-Jouvet ’26 in an ice bucket with two glasses so we don’t have to drink the cat-piss they serve in the dining car.”

It should not be surprising that a film about a luxury hotel features a few wine cameos. Nor should it be surprising that a comedy should make a joke of them. Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel more than delivers on both counts, and his characters’ stilted dialogue seems tailor-made for subtle wine farce. Characters pronounce wine names ridiculously, with baroque flourishes, only to quickly bury them under more talk. You have to be fast enough to catch the name, and faster still to catch that the name was actually a joke. This quirk makes Grand Budapest an oddly respectful film about connoisseurship—a certain amount of taste is required to comprehend what’s funny in the first place.

In Grand Budapest, Anderson rarely mentions a wine directly. He instead creates his own kind of ‘wine talk,’ fragmenting the obscure jargon of wine names, regions and styles, and stringing together passwords comprehensible only to the initiated. In an early scene, the owner of The Grand Budapest orders a red wine whose name I was not quick enough to catch, and then “a split of the brut.” Not a split of Champagne, nor a half-bottle of Pol Roger, Billecart Salmon Rosé, or Whatever Whatever. The former would have been obvious, and the second amateurishly showy. ‘A split of the brut’ delights in the absurdity of the language, its implied, abstracted violence (to cleaver a beast?) that can hardly be linked to that tiny bottle of dry Champagne. The server even brings a comically itty-bitty sample glass. Most sparkling wines are made dry, or ‘brut,’ and say so right on the label. As we rarely refer to a wine this way, (“I’ll have the brut”) the term slips under the surface of the cultural consciousness, its use reserved for eccentric experts.

A little later in the film, I wondered if Anderson had started to make things up. M. Gustave, the film’s intrepid concierge, demands a bottle of Pouilly Jouvet. I’m sorry—of Pouilly-Fuisse? A world-class Chardonnay from Burgundy, in Northeast France? Or Pouilly-Fumé, the renowned Sauvignon Blanc wines from the Loire river valley a little to the west? Is that what he meant by cat-piss– are they serving a cheaper Sauvignon Blanc in the dining car, maybe from South Africa or New Zealand? (Of course not, this is a period piece!) Going back to the script, he does in fact call for a Pouilly-Jouvet. A quick Internet search returned an answer that nicely fits Anderson’s nostalgic phantasmagoria.

At Allexperts.com, ‘John’ posted an inquiry to a ‘wine expert,’ asking if he knew of a Jouvet Pouilly-Fuisse, “an excellent wine but did not Bankrupt the vault [sic.]” In the mid seventies, it was about $10-15 dollars in a restaurant, and $9 to $10 in a store. Presumably restaurant mark-ups were much tamer then, although according to inflation calculators, a $10 bottle of wine would cost equivalently $43 now. The expert responds that Jouvet disappeared in the ‘80s, much like the Grand Budapest Hotel is supposed to have closed, sometime after the author-character visits in the late sixties, but before he wrote about the hotel in the mid eighties. Which is about the time young couples enjoyed bottles of Jouvet Pouilly-Fuisse in New York, an affordable luxury recalling a lost, less-modern Europe. The Tenenbaum children had probably just been born.

The Pouilly-Jouvet namelessly re-emerges near the end of the film, when M. Gustave, the owner’s younger self, and the owner’s wife repeat the train trip where they had first brought it. Before, police thugs hindered the owner and M. Gustave, but this time the scene is shot in black and white, there are real SS, and M. Gustave is arrested and assassinated off-screen. But not before the script directs him to throw his glass of wine into the face of his executors.

In Anderson’s world, wine is flamboyant but innocent, like M. Gustave, and the hotel itself. As M. Gustave and the hotel owner dually put it, “there are faint glimmers of civilization left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that was once known as humanity.” Wine is an absurd protest against militarism, modernism, and whatever else you can say Anderson’s Nazis represent. Yet its absurdity makes its resistance all the more potent. A happy indulgence, fine wine can neither integrate with modernity nor its mercenary expediency, and is lost to time instead.

————————-

This post is the first in a continuing column, What Were They Drinking?!, featured on The Nightly Glass, and occasionally co-posted here on The Hooded Utilitarian. I also wrote a longer piece on service in The Grand Budapest Hotel here.

Contemplative Strolling: How do Comics Represent this Type of Subjective Time? (Part 2 of a 3-part Series)

To continue my February 13, 2014 musings on time, I’d like now to focus on one particular type of perceived time: the subjective experience of the stroller, the old literary archetype of the flâneur.

We can situate this exploration in the larger domain of subjective time experience, and I am still using the crutch of “Duration in Comics,” Sébastien Conard and Tom Lambeens’ fine exploration of Henri Bergson’s notion of durée as it can be applied to narrative comics such as Kevin Huizinga’s Ganges and Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: Smartest Kid on Earth, as well as abstract comics, including Ibn al Rabin’s Drame de la non-communicabilité chez les phylactères [A Drama of Inability to Communicate among Speech Balloons] and Lewis Trondheim’s Bleu [Blue]. (European Comic Art 5:2, Winter 2012: 92-113). The reason I write “crutch” is that their article convinced me that there was sufficient cause for me to return to Henri Bergson’s thought in the original, and so I planned to engage in the usual literary scholar feint: hastily peruse relevant works over a weekend, select meaningful quotes, tear them out of context, insert into own train of thought, ignore larger framework of assertion—only to run into the following subtle shaming:

Me: Philosophy Colleague, do you have Henri Bergson’s works in your office?

Philosophy Colleague: Oh yes! He’s wonderful. Which ones are you interested in?

Me: I need Time and Free Will, just over the weekend. Working on a piece on time.

Philosophy Colleague: (furrowed brow) Just Time and Free Will? Surely, you need Matter and Memory?

Me: Ummm, yeah, I guess I do…. Thanks!

Philosophy Colleague: Have you read his Introduction to Metaphysics?

Me: Errr, no, I haven’t.

Philosophy Colleague: Well, you’ll really want to read that first; it’s a rather necessary introduction to Bergson’s thinking, and quite clear, too.

Me: Ahhh, yes, of course. (thin voice) I’d better borrow that, too. Probably going to need more than a weekend…

Philosophy Colleague: (chortles) Indeed. Keep them as long as you’d like. (Hands me tomes)

Not the first time I’ve perceived this difference between the two Humanities subjects: it seems that literary scholars have a bit in common with the avian family, Corvidae (crows and jays), as well as Ptilinorhynchidae, the Bowerbirds, in that we collect shiny objects torn from their contexts, arranging nifty new collections where, in the case of the bowerbird, tin can tops can sit in aesthetically pleasing juxtaposition to a spray of lilies and a bit of moss.

Philosophers, on the other hand, and to continue the bird analogies, carefully and systematically arrange their environment as the avian family Ploceidae, aka weavers, do: starting an elaborate hanging nest with an outer foundation of pliable fibers, and layering it with leaves, feathers and other soft things that will cushion the nestlings, stay round or tear-shaped, never get blown off the substrate, etc.

Anyway, back to the crutch issue. Philosophy Colleague, initial readings of An Introduction to Metaphysics and a bit of Time and Free Will, and my professional guilt have all convinced me to spend more time with Bergson, and this can’t happen until summer. So, I’ll continue to poach Conard and Lambeens, and you should keep Bergson in the back of your mind as I do so.

“Duration,” they write, paraphrasing Bergson, “is not a fixed representation of perceptible reality but changing reality itself. It is through intuition that we get a sense of duration and leave behind the everyday perception of things.” (96) [Hmmph…Philosophy Colleague was right, dagblast him; Lambeens and Conard are quoting not Time and Free Will here, but An Introduction to Metaphysics!] They mount a credible argument for the recognition of multiple types of time in the reading of a sequence of panels: the time it takes to read, which isn’t exactly the same as linear clock time in that the reader can slow down, speed up, reread, etc.; the number of panels [space] used to suggest time’s passage (which is why both comics critics and the sci-fi community often prefer the term spacetime: e.g. Noah Berlatsky speaking of “time and identity flattened out across space” in his April 13, 2013 Hooded Utilitarian post, “Flatland,” with Domingos Isabelinho adding in the comments section to this post, “I prefer the concept of spacetime….[T]here are images that Gilles Deleuze calls crystal-images in which more than one time continuum coexist as in the Watchmen examples above. Some comics panels are more sequences than frozen moments in time.” [April 15, 2013]).

Spacetime – highlighting the spatial aspects of the fourth dimension—works beautifully for comics, I think, as we are always moving across and around space (within single panels, across a page, splash or spread, non-contiguously across the pages of a comic as Thierry Groensteen and Pascale Lafèvre help us to understand in their theoretical works) to build up a sense of narrative. Narrative is, of course, a conceit of time. Reading time, diegetic (story) time, and perhaps the most fascinating of all: the interweaving of reading time with story time. Lambeens and Conard note that “…when reading, we live time very personally, in a tied bond with [the] main character.” (104) Though they do not cite Roland Barthes in their article, I do think that Conard and Lambeens operate off a similar distinction between readerly and writerly texts as that used by Barthes, where the “writerly” text demands high-level engagement, a kind of completion of the story by the efforts of the reader. Conard and Lambeens assert that it takes a special kind of relationship between comics reader and narrative, one that “keeps us immersed in a diegetic universe by actively letting a specific space-time emerge.” (106)

So, naturally, it would be fruitful to explore this relationship between reader and story in myriad ways; you could, for example, look at the way time slows down if the affective domain is engaged. I am thinking of Michael Johnson’s last Hooded Utilitarian/Pencil Panel Page post on comics that bring one to weep. I would imagine that panels that move us in this way also slow us down, if not to study them more carefully, then certainly to wipe away tears, snurfle, have our own memories/dreams/reflections for a moment…. Why, isn’t “slow down” a major tenet of our instruction to students—if we teach comics—as we alert them to the necessity of working with the comics text on its own terms, treating it as a rich word and image-based work that demands effort from readers?

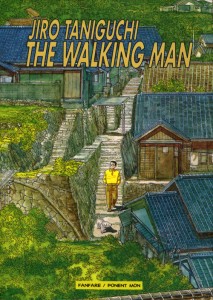

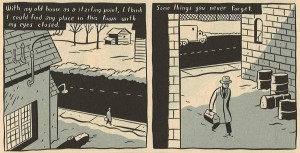

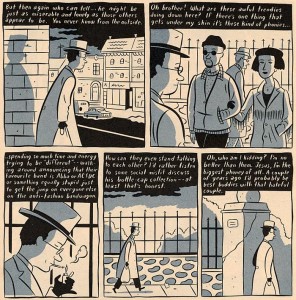

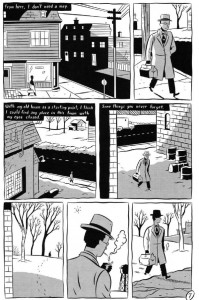

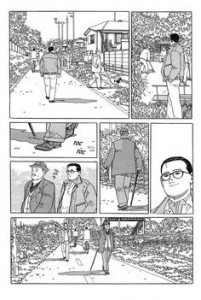

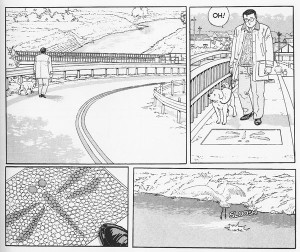

Okay, enough context. So, why do I choose to examine the flâneur in comics? First of all, they are everywhere: Ghost World, Jimmy Corrigan, Palestine, Batman, Little Nemo, Carnet de Voyage, Tintin. Second, their leisurely movement down a street, lane, trail ideally depicts contemplation as it allows the comic artist to break up the slow walk into contiguous panels that move aspect-to-aspect (in McCloud’s words), sometimes following the gaze of the walker, and at other times, allows the artist to overlay the scene with panels that are, or might be, memories of the same place at another time, another place, even an odd, seemingly unrelated connection. The flâneur also becomes the perfect vehicle for sustained internal monologue that can be captured in rather text-heavy balloons (as is sometimes the case in Seth’s It’s a Good Life if You Don’t Weaken) or without them, as in Jiro Taniguchi’s mostly silent The Walking Man.

Seth’s and Taniguchi’s flâneurs are not the urbane, hyper-performative types you might find in late 19th century French literature or Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood. They are closer to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s self-depiction in Reveries of a Solitary Walker and Alfred Kazin’s thoughtful Spaziergänger in A Walker in the City. These strollers animate their thought by walking, as Kant did, as Kierkegaard did; they are within the philosophical tradition of reflective walkers. In It’s a Good Life if you Don’t Weaken, the seemingly autobiographical figure (we’ll call him Seth for convenience) makes his way around the small town of Strathroy in the province of Ontario, Canada, flooded with memories, but also critically observing what is actually around him:

The panels work us around the scene, but also slow us down to look at Seth, engaging in the cigarette lighting process that often occupies the penultimate panels of a page that presents a sequence of mobile thought. Such a set of images calms and quiets the reader (as aspect-to-aspect often does), and puts him/her into the optimum state to reflect along with the protagonist. The duration here is lengthened just so; the number of panels, views, aspects determines—at least in part—the length of time we will devote to the page. Slowed down, unstimulated by overt action, we can enter into the shared subjective time theorized by Conard and Lambeens above, “…liv[ing] time very personally, in a tied bond with [the] main character.” (104) This process works even more effectively when the main character’s thoughts are sketchy, occluded, hinted at, as in this page from Seth:

Though “Some things you never forget” aptly summarizes the preceding panels, it also opens up into a more liminal space in the last three, silent, panels, as we consider both what Seth might also be remembering, and as we, perhaps, start our own sequence of memories, triggered by the non-accidental use of the second person: Some things you never forget.

This scene from Jiro Taniguchi’s The Walking Man (just a reading note: though this is a Japanese comic, it is read left to right in the Western manner) may not significantly reveal the walker’s thoughts, but it does present a human-to-human connection that is fleeting, non-verbal, and non-reciprocated:

Watching the protagonist notice, gain on and pass the old man gives us insight into his character (he is interested in those he passes, he notices them), and if the page were parsed further, would probably lend itself to a valuable study of panel-to-panel changes in both diegetic action time (he appears to speed up), and duration.

The walker in Taniguchi’s comic is also equally interested in animals, weather, objects: everything he sees, hears and feels (rain figures prominently in a later sequence of panels) appears to bring him pleasure:

As we take this stroll with Taniguchi’s walking man, we see the world with him, learn about his character, walk vicariously, think our own thoughts, experience—maybe—rapprochement with him, and with the world itself. Can you remember other meditative strollers in the comics you know best, or do you have something to say about duration/subjective time more generally?

Does This Post Need a Trigger Warning?

So this is a bit different than what I usually post here, mainly because I thought I’d be posting it somewhere else. But that didn’t work, so at HU it is. You can consider that a warning of sorts, I suppose.

_________

In Patricia Hill Collins’ classic monograph Black Feminist Thought (2nd edition, 2000), she describes seeing a difficult presentation by a White feminist scholar. The lecture was about Sarah Bartmann, a Khoikhoi African woman who was displayed as a freak show novelty under the name the Hottentot Venus in 19th century Europe. The scholar, Collins says:

In Patricia Hill Collins’ classic monograph Black Feminist Thought (2nd edition, 2000), she describes seeing a difficult presentation by a White feminist scholar. The lecture was about Sarah Bartmann, a Khoikhoi African woman who was displayed as a freak show novelty under the name the Hottentot Venus in 19th century Europe. The scholar, Collins says:

“refused to show the images [of Bartman] without adequately preparing her audience. She knew that graphic images of Black women’s objectification and debasement, whether on the auction block as the object of a voyeuristic nineteenth century science or within contemporary pornography, would be upsetting to some audience members. Initially I found her concern admirable yet overly cautious. Then I saw the reactions of young Black women who saw images of Sarah Bartmann for the first time. Even though the speaker tried to prepare them, these young women cried.”

The white feminist scholar Collins is discussing here could be seen as providing an early form of trigger warning — a notification intended to warn people of content that may cause a painful or damaging emotional reaction.

As Collins’ anecdote shows, trigger warnings have existed for a long time in informal settings. But they became codified on the internet, especially on feminist websites and blogs. Feminist internet trigger warnings focused on sexual abuse or torture, suicidal or self-harming behavior, and eating disorders, according to the Geek Feminism Wiki. The goal of these warnings was to alert survivors of sexual assault, or those with a history of suicide attempts or eating disorders, that the article might trigger PTSD or anxiety. “Someone who is triggered,” according to Melissa McEwan, “may experience anything from a brief moment of dizziness, to a shortness of breath and a racing pulse, to a full-blown panic attack.” Andrea Garcia-Vargas, a PolicyMic columnist who writes about the intersection of gender, sex, and tech, argued in an email to me that such warnings are:

…absolutely necessary. Why? Because PTSD in response to depictions of violence (particularly sexual violence or war violence) is a very real issue, and people who may be triggered by violent images or depictions deserve a “heads-up” that it’s coming. That’s not to say that the trigger warning is going to completely stop PTSD. Of course it won’t. It’s only one step. But it’s a very necessary step. With the trigger warning, the reader can decide whether or not they are in a frame of mind to proceed.

Many writers use trigger warnings as a matter of course. There’s one on McEwan’s article, for example, and one on this piece by Soraya Chemaly at the Huffington Post. Some commenters, though, argue that the warnings aren’t all that helpful. Amanda Marcotte, for example, notes that

“I write often about difficult subjects like rape and abortion, but I never use trigger warnings. My experience is that the audience can do a better job than I can at figuring out what kind of content will upset them by reading the headline than I ever could randomly guessing what blog posts count as triggering.”

Along the same lines, Jill Filopovic points out that PTSD “triggers are often unpredictable and individually specific — a certain smell, a particular song.” Trigger warnings suggest that you can protect people from traumatic reactions, which isn’t necessarily the case.

Filopovic agrees that it’s reasonable to provide warnings for the most common triggers like sexual assault or eating disorders on feminist blogs. She and others, however, have become worried that the use of trigger warnings is moving off the internet and into other real-life venues, especially college classrooms. Oberlin College (my alma mater) has recently put out an official discussion of triggers, advising faculty to “strongly consider” making “triggering material” optional for students. Among the books that were suggested as being triggering was Chinua Achebe’s classic Things Fall Apart, which Oberlin warns might “trigger readers who have experienced racism, colonialism, religious persecution, violence, suicide and more.”

Some argue that the use of trigger warnings in a classroom setting may do more harm than good. Emory sociology PhD candidate Tressie McMillan Cottom worries that trigger warnings play into a model where students are perceived, not as learners, but as customers, who are never supposed to feel any discomfort. Trigger warnings then become part of a system which works “to rationalize away the critical canon of race, sex, gender, sexuality, colonialism, and capitalism” — students who don’t like discussions of racism or colonialism will never have to confront their prejudices or preconceptions. Jenny Jarvie at The New Republic goes even further, arguing against trigger warnings not just in college settings, but online as well. “Structuring public life around the most fragile personal sensitivities will only restrict all of our horizons,” she says. “Engaging with ideas involves risk, and slapping warnings on them only undermines the principle of intellectual exploration. ”

I can see the virtues in the arguments both for and against trigger warnings — and partially as a result, I feel like both may be framed in overly absolutist terms. To me, it seems like it might be better to think about trigger warnings not as a moral imperative, but rather as a community norm. Warnings exist, after all, in dialogue with reader expectations. In some forums, people may expect to be warned about difficult content. In other cases (as with Amanda Marcotte’s posts) readers will have a sense going in that sensitive issues are going to be discussed with some regularity.

Negotiating exactly when and where there needs to be a warning, and what kind of warning, then becomes something that different communities can work out differently. Marcotte, for example, mentions a recent episode of the television show Scandal in which a major character was raped. Many fans responded with anger, insisting that the show should have included a trigger warning — and the show’s creator, Shonda Rimes agreed with them. You could see this as the show failing in its moral duty to protect its fans. Or you could see it as Rimes caving to oversensitive censorship. But it seems like it might be more useful to see it simply as a particular community figuring out how it wants to deal with charged material.

This doesn’t mean that writers have no ethical obligations when discussing difficult content. On the contrary, it seems like trigger warnings are just one possible way of dealing with one’s obligation to deal thoughtfully with such material. Angust Johnston, a historian and founder of studentactivism.net, wrote to me in an email that:

“content warnings are a part of a larger set of questions about how you’re interacting with your readers. Are you shocking them for the sake of shocking them? If so, content warnings are just a fig leaf. On the other hand, if you’re being careful about how you approach a subject, I think you can often write your way around the need for them.”

Johnston added that this applies offline in a classroom context as well. “I think professors have an obligation to recognize that their students are human beings who may have strong emotional and psychological responses to class materials and discussions, and to deal with those responses in a respectful and sympathetic way,” he said. Content warnings could encourage professors to think about those issues, which would be good — but they could also be a way, as Tressie McMillan Cottom suggests, to avoid important issues. Content warnings themselves are just a tool, which can be used well or badly. The real ethical imperative is to approach an audience, whether online or off, with, in Johnston’s words, “thought and care (and humility.)”

In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins describes another, less sensitive presentation on Sarah Bartmann. A White male scholar lecturing about historical scientific racism included pictures of Bartmann as part of his PowerPoint presentation.

“Leaving the image on screen for several minutes with a panel of speakers that included Black women seated on stage in front of the slide, this scholar told jokes about the seeming sexual interests of the White voyeurs of the nineteenth century. He seemed incapable of grasping how his own twentieth-century use of this image, as well as his inviation that audience members become voyeurs along with him, reinscribed Sarah Bartmann as an “object…a malleable ‘thing'” upon which he projected his own agenda.”

The issue, then, is not simply including or failing to include a warning. The issue is recognizing your own relationship, as a writer or presenter, to race, gender, violence, and other intersections of power. Trigger warnings can be one way to do that, but the argument about them pro or con shouldn’t be allowed to obscure the main goal. That goal, as Johnston says, is to treat your audiences, or audiences, as human beings.

Off to Never-Never Land

First time I lost a tooth, I ran to the top of the steps and yelled, “My tooth came out!” I couldn’t see my mother in our laundry room, but she performed a reasonably convincing shout of excitement, ending with: “Looks like someone’s getting a visit from the tooth fairy tonight!”

My five-year-old body went rigid. Blood drained from my face. Tooth fairy? Who the hell was the tooth fairy?

I must have a gothic disposition, because I assumed this creature would be coming for the rest of my still-attached teeth. One of Poe’s narrators does that, plucks out his beloved’s beautiful incisors and bicuspids with a pair of pliers. But Germany’s E. T. A. Hoffman is the better source for inverted fairies. A student in my English Capstone assigned the 1816 “Der Sandmann” to our class earlier this semester. Hoffman takes the harmless Sandman, bringer of sleep to dozy children, and twists him into “a wicked man” who “throws handfuls of sand into their eyes, so that they jump out of their heads all bloody; and he puts them into a bag and takes them to the half-moon as food for his little ones.”

That’s the guy Metallica is singing about. Although the Hans Anderson version isn’t all goodnight kisses either. Ole-Luk-Oie, the Dream-God, may be very “fond of children,” but if you’ve been naughty, he holds a black umbrella over you all night so come morning you’ve dreamt nothing at all. His sibling is named Ole-Luk-Oie too, except “he never visits anyone but once, and when he does come, he takes him away on his horse, and tells him stories as they ride along. He knows only two. One of these is so wonderfully beautiful, that no one in the world can imagine anything like it; but the other is just as ugly and frightful, so that it would be impossible to describe it.” The other Sandman isn’t a Dream-God. He’s Death.

I prefer Hoffman’s eye-plucking fairy. He reveals “the path of the wonderful and adventurous” as the child-narrator tries to unmask him. That’s right, “the terrible Sand-man” is a dual-identity supervillain. The kid recognizes his father’s business partner, a literally Satanic lawyer who practices alchemy by night. If the Faust allusions aren’t clear, then note his “sepulchral voice” and the laboratory explosion that kills the hapless dad. Hoffman even quotes Goethe after strumming the ubermench theme song: “Father treated him as if he were a being from a higher race.”

Enter Golden Age comic writer Gardner Fox. He must have spent a lot of time under Ole-Luk-Oie’s other umbrella, the one with the pictures twirling on the inside. He dreamt up the Flash, Hawkman, Dr. Fate and the Justice Society of America. Bill Finger usually gets credit as Batman’s original writer, but Fox wrote six of the first eight episodes, each almost twice as long as Finger’s introductory 6-pagers. Instead of apprehending jewel thieves and serial killers, Fox’s phantasmagoric Dark Knight faces down a werewolf-vampire and some guy who steals faces and puts them on talking flowers.

When Finger returned Batman to the grit of crime alley in 1940, Fox dreamt up the Sandman, your standard fedora-wearing Mystery Man, except in a World War I gas mask. He stole his knock-out pellets from Batman’s utility belt (a Fox invention), though they’d already been field-tested by Johnston McCulley’s Bat and WXYZ’s Green Hornet. When Jack Kirby and Joe Simon got tired of spinning Timely’s umbrella of characters, they traded in the Sandman’s business suit for a red and yellow leotard and a sidekick named Sandy. They kept the color scheme when they revised him again in 1974, this time as the Sandman of Hans Anderson lore, a protector of children’s dreams. That’s the dopey series Neil Gaiman reawakened in 1988.

I was too busy mourning the collapse of Alan Moore’s short-lived Mad Love company to take adequate notice at the time. Gaiman stripped off the leotard, but I still considered his white-skinned Morpheus just another superhero reboot. I thought the future of comics was Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz’s Big Numbers and Dave McKean’s Cages. I was wrong. McKean’s publisher Tundra died almost as fast as Mad Love. I’m sure he made better money painting Sandman covers anyway.

Sandman is easily the best-selling and best-regarded comic of the 90s. When I attended a comics forum last month, it was the only work to receive its own three-scholar panel. Unfortunately the forum was in Michigan after a bout of “snow thunder” had reduced the state to a lake of frozen slush, and none of the three panelists showed up. Maybe the empty podium was their way of evoking a night spent under the Sandman’s black umbrella.

I prefer Gaiman’s non-graphic novels anyway. Stardust was one of the last books I read aloud to my kids, my wife regularly teaches American Gods, and Coraline once shattered an MFA-induced writing block of mine, not just its twirling dreamscape, but the deceptively Stein-esque simplicity of its sentences. This also lea\d to a parenting low point when my wife and I refused to leave a matinee of the film adaptation even though our son was trying to claw over the back of his seat to escape. And yet the emotional scars did not prevent him from later writing a book report on Neverwhere. He likes Good Omens too.

Like Hans Anderson, DC spun-off the Sandman’s sibling Death, but when Gaiman killed Sandman, his contract stipulated that it would stay dead. Because, as Ole-Luk-Oie warns his listeners, “You may have too much of a good thing.” I was paying enough attention to buy that 75th and final issue, a riff on Shakespeare’s Tempest. It turns out the bard is a bit of a Faust himself. The talentless hack accepts a contract as the Sandman’s front man, inundating the world with dream stuff for centuries to come. “There is nobody in the world,” wrote Hans, “who knows so many stories as Ole-Luk-Oie, or who can relate them so nicely.”

Asterix and the Bland Sequel

1960, and I am 6 years old; I leave the New York Public School system for my first day at the Lycée Français de New York, the city’s French school. (I’m half Yank, half Frog.)

At the end of the day, my mother rewards me with a comics album; it features a hero I’ve never heard of, in his first adventure — Astérix le Gaulois. It was the start of a love affair that lasted until the death of the comic’s writer, the brilliantly funny René Goscinny (1926-1977).

René Goscinny

The team of Goscinny (script) and Albert Uderzo (art) produced 24 albums of adventures for Astérix and his hulking sidekick Obélix. The series sold fairly well at first, but by 1965 it had become a hit phenomenon, one that grew and grew from year to year.

Goscinny and Uderzo at work; art by Uderzo

Alas, Goscinny died too soon, age 51. His partner then made a fateful decision that would prove financially successful but artistically disastrous: he would continue the series alone.

It’s part of received wisdom that the best comics are the product of a single writer/artist, and indeed there are many examples to support this view: Schulz (Peanuts), Herriman (Krazy Kat), Crumb. It can also be persuasively argued that even cartoonists who did good work in collaboration with others, for instance as scripters (Harvey Kurtzman) or artists (Jean Giraud, Barry Windsor-Smith) did their best work solo.

The Goscinny-Uderzo team tests this tenet. Goscinny was a mediocre cartoonist who wrote excellently. Uderzo is an excellent artist…who writes very badly.

The classic team at work…

Where Goscinny had impeccable comic timing, Uderzo’s lame gags seem to plop onto the page. Where Goscinny’s stories were intricately plotted, Uderzo’s are simplistic good guy/bad guy fables with sentimental love tales woven in. Goscinny wisely limited the fantastic element mainly to the famous Magic Potion that gave Astérix super-strength; Uderzo crammed his albums with flying carpets, unicorns, Atlantis, giant babies, flying saucers and all the fantasy paraphernalia you could wish for — or not. (Actually, I have a sneaking sympathy for the artist on this last point: he had probably felt frustrated by decades of not being able to draw all this cool stuff…)

I could go on in depressing detail, but suffice it to say that over the course of eight albums what was once widely hailed as the world’s best comic, beloved of kids and adults alike, had descended into a silly, wholly childish mediocrity.

But in business terms, Astérix had become a colossus.

To give some perspective, consider that the first edition of the first album, back in 1959, was of 6000 copies. In 2005, Uderzo’s last album had a first edition of three million two hundred thousand copies — and that’s just the French language version.

Published in 110 languages, Astérix has had to date total worldwide sales of 350 000 000 copies. It has spawned 8 feature cartoons, 4 live action feature films, and an amusement park. It currently has over 100 product licenses. This is a billion-dollar property.

And one which has turned Uderzo, especially since he took over the publishing himself, into one of the richest men in France.

But the artist is now 86 years old, and determined to retire. At first he thought of discontinuing the strip as well…then decided to turn it over to a new team: scripter Jean-Yves Ferri and artist Didier Conrad.

Left to right: Jean-Yves Ferri, Albert Uderzo, and Didier Conrad

It’s not a choice a purist would wish, perhaps, but one can understand the impulse behind it. Uderzo is probably hoping to pass on a living, profitable legacy to his descendants (though as of this writing he’s embroiled in a nasty lawsuit against his daughter.) He might also feel a duty towards the employees of his company. Who knows? He might simply have thought it fun to oversee the work of new blood.

Ferri (1959– ) was best known for an album of mildly whimsical gags, De Gaulle à la Plage. Conrad (1959– ) was once considered a satiric and scatological enfant terrible of Franco-Belgian comics — little trace of that here — renowned for his skill at imitating classic cartoonists such as Franquin or Morris; this latter talent is, no doubt, the reason Uderzo chose him.

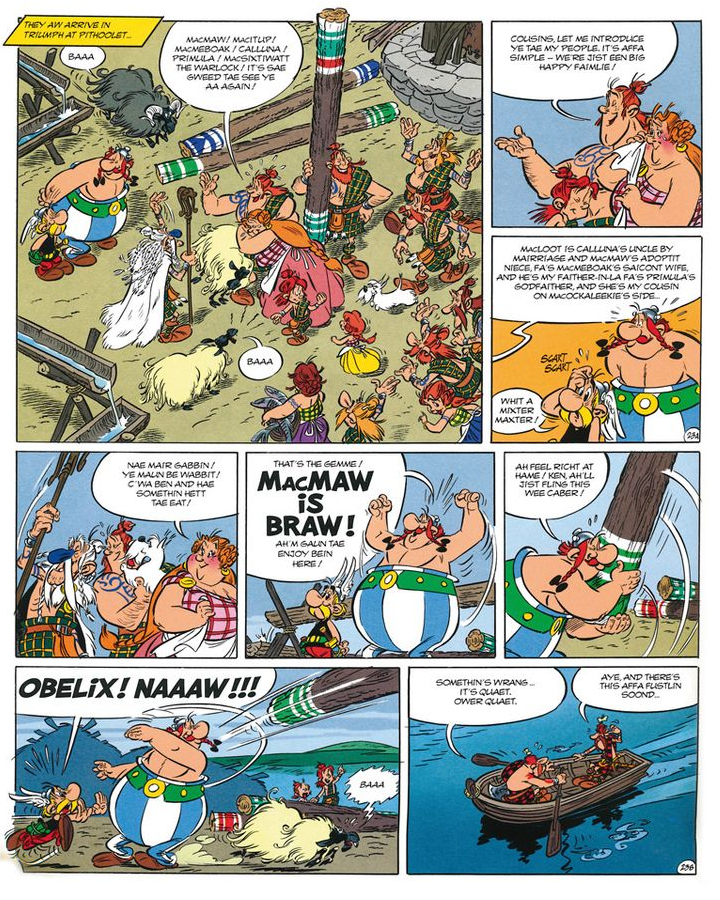

October 2013 saw the release of the new team’s first effort, Astérix chez les Pictes.

My verdict, and that of most reviewers: FAIL.

Some background: Astérix, in album after album, would visit a foreign land, and the people dwelling there would be satirised: Belgians, Swiss, Spanish, Germans (the only ones treated really viciously: understandable, perhaps — the Jewish Goscinny lost part of his family to the Nazi extermination camps.) By common consensus, the best of these particular albums is Asterix in Britain, a hilarious send-up of the English, who themselves loved it.

The target country this time around is Scotland. (The Picts were the Celtic tribes who pre-dated the Scots in what the Romans called Caledonia.)

Now, not everybody likes these national parodies, and indeed one may argue that they reinforce stereotypes and xenophobia. (One comics scholar of this opinion I found rather persuasive is Domingos Isabelinho.) However, if you’re going to satirise, then do it: don’t turn out soft-pedal mush!

Alas, that’s exactly what Pictes does. There’s some wordplay on Mac-prefixed names, fun at the expense of clan tartans or of the Scottish sport of caber-tossing, teasing about the potency of proto-scotch whisky…and that’s about it. I’m not asking that Ferri dig up the more nasty clichés about the Scots, especially the libelous legend of their niggardliness. (I’ve travelled in Scotland, and have found the Scottish people to be of extraordinary generosity and kindness.)

But why such blandness? It’s telling that throughout, the Gauls and the Picts call each other “cousin”. That’s what we get here: the Picts/Scots are just Gauls/French in kilts.

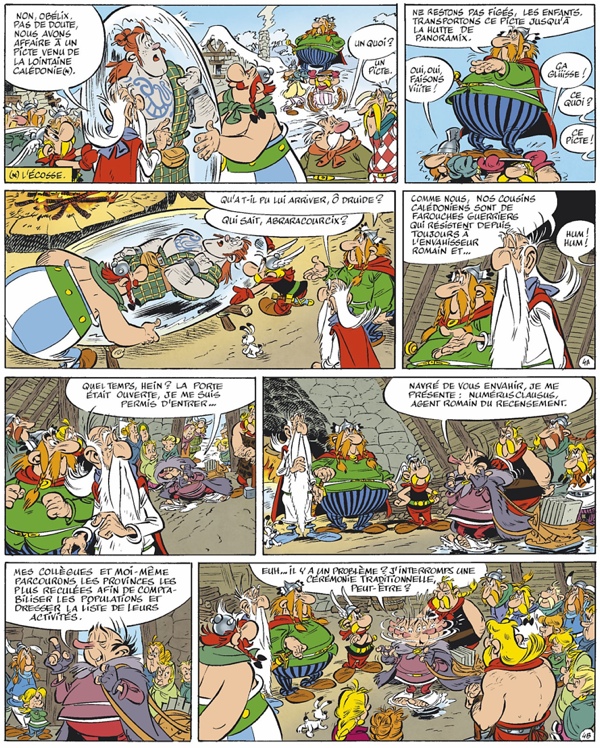

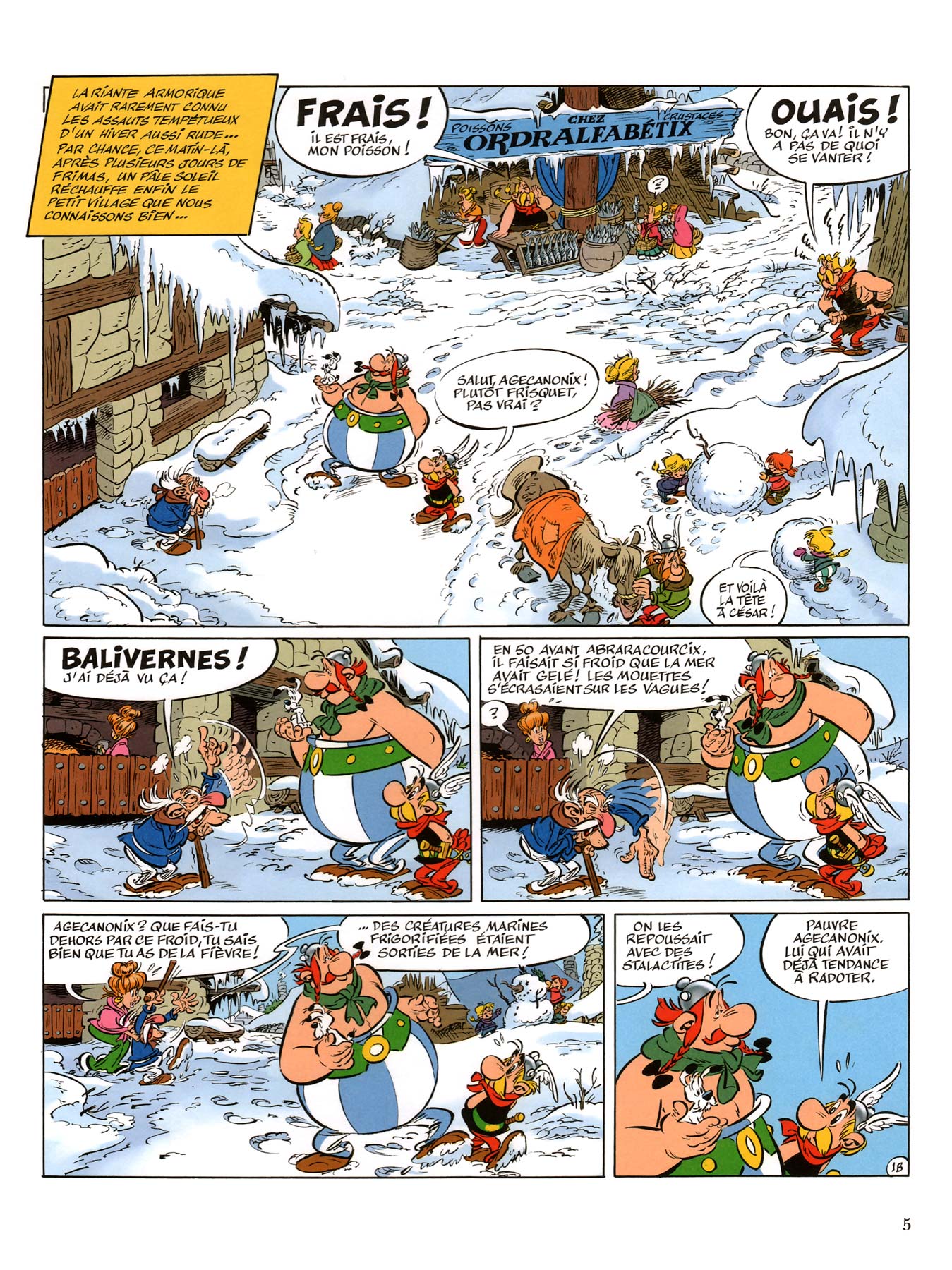

Well, on to the story, such as it is. It’s winter in Gaul, and Asterix and Obélix find a young Pictish man frozen in ice:

Once the Druid thaws him out, the Pict is unable to speak at first, but manages to carve a map to his home village.With Asterix and Obélix they set sail — which naturally means the traditional running gag of trashing the pirates. (The Pict, Mac Oloch, recovers his power of speech.)

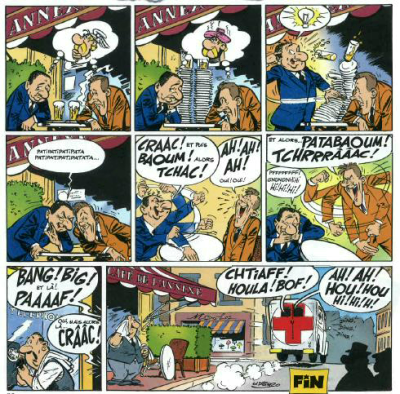

The pirate fight seems unusually bullying this time around — as a rule they do something to bring down Gaulish wrath on their heads. This time it’s see-pirate, bash-pirate: gratuitous violence:

(The above image shows a recurring flaw in Conrad’s impersonation of Uderzo: the latter was very good at clarity in complex set-ups — his successor, not so much.)

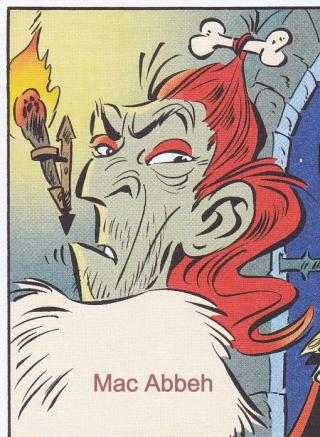

They get to Caledonia, there’s a big welcome back, and the goodies vs baddies scenario is laid out. The villainous Mac Abbeh is scheming to take over as Great King of the Pictish Clans, and he’d caused Mac Oloch’s supposed frozen doom to set aside this rightful pretender, as well as to steal his fiancée Camomilla. He’s also plotting with the Romans to have them invade Caledonia (which they never managed in real life).

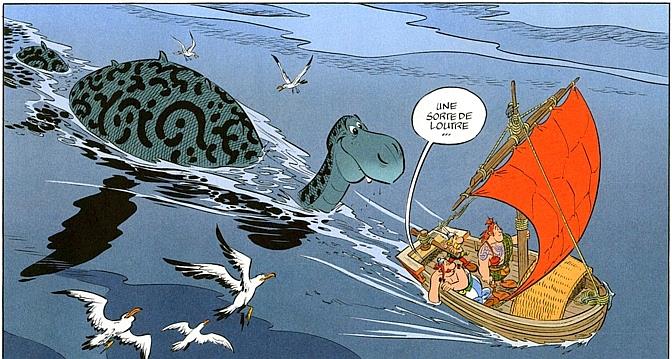

Our heroes set to work undoing this villainy, as usual with plenty of smashing the enemy, interspersed with salmon feasts, joking assimilation of Pictish bards with rock groups, whisky-sodden druids and Romans, and an excessively goofy-looking (and overexposed — see my complaints about too many fantasy elements) Loch Ness monster:

Goscinny would often slip in political or sociological commentary into his scripts. The closest Ferri comes to this is rather mean-spirited: during the final battle, in a free-for-all between warring clans, we note that each clan is distinguished by a tartan or other pattern, often ridiculous — polka dots and so on. The representative of the White Pict Clan bears the insignia of the Red Cross, and he proudly proclaims his neutrality — which leads to his being beaten up by both sides, to the evident approval of the authors.

The Red Cross (as well as its Islamic sister organisation, the Red Crescent) has always proclaimed and studiously observed its neutrality during war and conflicts. It has to. It otherwise couldn’t fulfill its mission of tending to the wounded and prisoners held by each enemy combatant. To sneer at the Red Cross for its neutrality is as distasteful an attitude as I can imagine.

Another annoyance for this olde farte of a reader: the series used to be stuffed to the gills with classical allusions, often of a very high degree of wit. None of that here. But I suppose I can’t really blame the authors. France in 2014 is not the France of 1959, when Latin was a compulsory subject in middle and high school, when most of the country went to the Latin-language Roman Catholic mass every Sunday (Asterix debuted before the Vatican II Council imposed the mass in the vernacular.) The country, and most of Europe, was steeped in classical culture. An age lost and by the wind grieved…

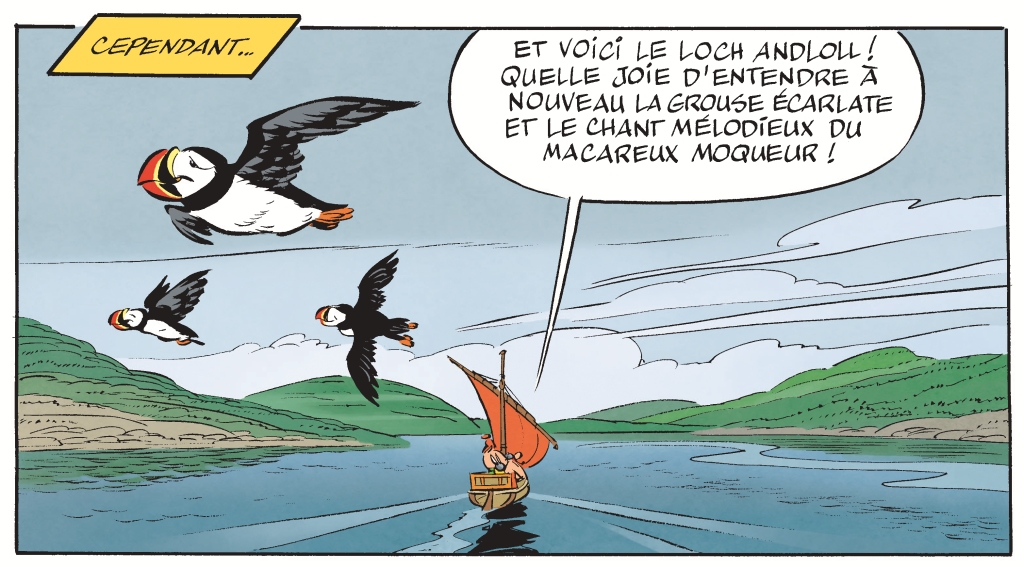

Are there any positive sides to the album? As I said, Didier Conrad is a pale echo of Uderzo, but sometimes his art can depict images of simple charm, such as this view of low-flying puffins:

MacOloch’s brain-damaged state is treated with genuine tact and sympathy, showing his sadness and frustration at being unable to control his speech:

I liked how the entire Gaul village rallied around this stricken castaway with kindness and tact. There is a minor sub-plot concerning a modest but zealous Roman census-taker that I also enjoyed.

There is also the refreshingly feisty figure of Camomilla, MacOloch’s lady love. He’d described her in the most cloying, sylph-like romantic flummery — but when we get to meet her she’s a short, plumpish firecracker of a lassie with a temper and a quick-lashing fist. Even MacOloch is a bit afraid of her and of her heretical feminist notions about royal succession.

To sum up, the book isn’t bad as such. It’s mediocre, and mediocrity doesn’t cut it when it comes to a once-extraordinary strip like Asterix.

The English-language version is also out, as usual translated by Anthea Bell (1936– )

Anthea Bell

Bell is one of Britain’s most esteemed and honored translators from the French, German and Danish. Although she is noted for her work with adult literature (Stefan Zweig, W.G.Sebald, Sigmund Freud) she also has a considerable body of work in children’s literature (new translations of Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tales) and comics. Her renderings of the Asterix books are remarkable, especially in her skillful versions of puns — the translator’s nightmare — and of cultural allusions.

Alas, her work here really can’t be commended. Uninspired is the best I can say. Look at the first panel in the page below, which carries on one of the series’ running gags, the enmity between the fishmonger and the blacksmith in the village:

Fishmonger: Frais! Il est frais mon poisson!

Blacksmith: Ouais! Bon, ca va! Il n’y a pas de quoi se vanter!

There’s a pun at work here. My literal translation:

Fishmonger: Fresh! My fish is fresh!

Blacksmith: Yeah, yeah! That’ll do! That’s nothing to brag about!

Now, the caption and the graphics tell us that this is an exceptionally cold winter. In French, “frais” can mean either fresh — as in ‘fresh fruit’ — or cold. So the punning meaning implied by the blacksmith is that his old foe is bragging about his cold fish, and so what in weather like this?

Whew. How do you translate a pun like that? Don’t ask me, but in the past Bell has pulled off miracles in this linguistic minefield. Not here, though: her translation runs:

Fishmonger: Fresh fish! Buy my nice fresh fish!

Blacksmith: Huh! Fresh, is it? Tell us another!

In other words, Bell doesn’t even try.

Mind you, she can’t be blamed for making bricks without straw. At one point the Picts welcome Asterix and Obelix with a feast of “paupiettes de saumon”, salmon paupiettes. Now, paupiettes are thinly sliced pieces of meat wrapped around a filler of vegetables and stuffing. But Conrad just draws whole salmons in the dishes. Poor Bell can’t remedy this laziness by just calling them ‘salmons’, as there’s a whole little shtick about Obelix loving the dish and asking for the special recipe. So Bell calls them “salmon portions”.

(Foreign dishes are a recurring source of humor in the series. So why didn’t the authors mention the most famous dish in Scotland, the haggis, a meat pudding wrapped in a sheep’s stomach? Even the Scots make fun of it, vide Robert Browning’s ode to haggis (“Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face, Great chieftain o’ the puddin’-race! Aboon them a’ ye tak yer place, Painch, tripe, or thairm: Weel are ye wordy o’ a grace As lang’s my airm.”). My guess is that Ferri and Conrad didn’t want to invite comparison with one of the most famous skits in French radio: La Panse de Brebis Farcie, by Fernand Raynaud, about a Frenchman’s desperate attempt to avoid eating haggis.)

My main beef is that Bell made no attempt at reproducing Scottish dialect. All her Picts speak like London schoolmistresses. This is all the more bizarre as there’s also being published the entire album in Lallans, or Lowland Scottish English, as shown below:

(It’s also being published in Gaelic).

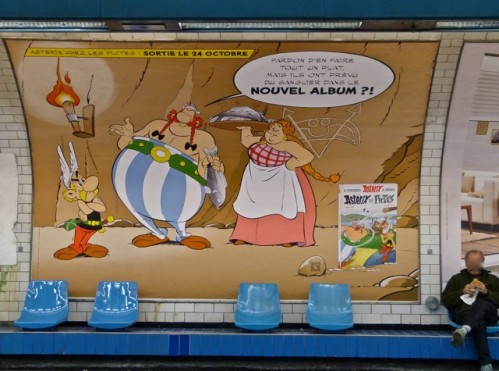

Finally, a last reason for my disenchantment. Comics are big business in France. The combined first printing of Picts comes to 4 million four hundred thousand copies, with 2 million two hundred thousand for France alone (at nine euros a pop- about $13…you do the math.) An Asterix album is given the media and advertising saturation launch of a Hollywood movie. For weeks, you couldn’t avoid the damn thing. Enough already.

Poster in the Paris metro

The problem of the legacy strip is common to France and the USA. In France, sequels to many popular series like Blake et Mortimer come out after the creator’s death, as do strips like Flash Gordon or Annie in the states. Other strips are permanently retired: Tintin, Peanuts. Which is best?