Zarathustra came down from the mountain in 1883. He’s Nietzsche’s reboot of the ancient Iranian prophet Zoroaster—which means the first Superman came down from a mountain in Asia. It’s been a popular continent for superheroes ever since. When DC rival Victor Fox needed a Superman knock-off for Wonder Comics in 1938, artist Will Eisener sent Wonderman to Tibet where a turbanded Tibetan was handing out magic rings.

Wonderman couldn’t survive the kryptonite of DC’s court injunction, so for Wonder Comics No. 2 Eisner swapped his colored tights and briefs for a tuxedo and amulet-crested turban. Yarko the Great was one of a dozen superhero magicians to materialize in comic books over the next three years. Nine of them shopped at the same turban store—though Zanzibar the Magician got confused and grabbed a Turkish fez instead. Three of them imported Asian servants too.

The tights-and-brief crowd rallied and sent a half dozen new supermen East, three specifically to Tibet, with Egypt as a solid runner-up. My favorite, Bill Everett’s Amazing Man, is almost as naked as his earlier Speedo-sporting Sub-Mariner, but Amazing Man has the power of the Tibetan Council of Seven on his side. He could also turn into “green mist,” which must have annoyed the hell out of the Green Lama. Jack Cole threw in a Fu-Manchu supervillain too: the Claw attacks America from “Tibet, land of strange religions and mysterious customs.”

When Stan Lee’s boss gave him the same assignment (do what DC is doing), he bee-lined back to Tibet for his and Jack Kirby’s first (and mostly forgotten) attempt at a superhero, the 1961 Doctor Droom. Kirby even gives the formerly Caucasian physician slanted eyes and a Fu Manchu moustache as his lama explains: “I have transformed you! I have given you an appearance suitable to your new role!”

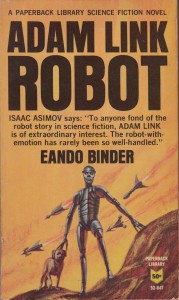

Droom flopped, so Kirby sketched an iron mask and Lee dropped the “r” and, voila!, supervillain Doctor Doom was born. The following year Doom was “prowling the wastelands of Tibet, still seeking forbidden secrets of black magic and sorcery!” Another year and Doctor Strange returns from Tibet as “Master of Black Magic!” Strange also picked up Wong, one of those handy manservants Tibetans hand out with their superpowers. The third Doctor emptied Lee’s Tibetan well, but Roy Thomas and Gil Kane’s Iron Fist kept Orientalism thriving at Marvel into the 70s.

Over at Charlton Comics, Peter Morisi’s Thunderbolt returned from his Tibetan adventures with the standard superhero package. Since Alan Moore’s Watchmen were borrowed from Charlton characters, twenty years later his Ozymandias not only “traveled on, through China and Tibet, gathering martial wisdom” but was “transformed” by “a ball of hashish I was given in Tibet” and next things he’s “Adopting Ramses the Second’s Greek name.” Even the 21st century Batman, as retooled in Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, hops over to the Himalayas to learn his chops from yet another monkish mentor. And you’ll never guess where director Josh Trank sends his teen superhuman for the closing shot of the 2012 Chronicle.

The 1930s mystery men loved the Orient too. Before Walter Gibson’s Shadow emigrated from pulp pages to radio waves, he first “went to India, to Egypt, to China . . . to learn the old mysteries that modern science has not yet rediscovered, the natural magic.” When Harry Earnshaw and Raymond Morgan conjured Chandu the Magician for film serials, they sent their secret agent to India to study from another batch of compliant yogis. And not only did Lee Falk’s comic strip do-gooder Mandrake the Magician pick up his powers in Tibet, his Phantom found his dual identity in the India knock-off nation of “Bengalla” (which magically wanders to Africa in later stories).

Before Doctors Strange, Doom and Droom (not a practice included in Obamacare) earned their degrees in Tibet, Doctors Silence, Van Helsing and Hesselius interned their first. You can add Siegel and Shuster’s pre-Superman vampire-hunting Doctor Occult to the list of eligible providers too. Like those turban-obsessed magicians, these world-touring physicians are armed with Oriental knowhow. Algernon Blackwood’s Silence was a 1908 mummy-battling best-seller, cribbed from Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula. Stoker’s Van Helsing is an expert on “Eastern Europe” and labels his vampire nemesis “a man-eater, as they of India call the tiger who has once tasted blood of the human.” Joseph Sheridan LeFanu’s 1872 Dr. Hesselius hunts vamps too, but his first patient is an English reverend driven to suicide by visions of “a small black monkey” caused by his addiction to the “poison” green tea imported from China, ever the land of strange religions and mysterious customs.

Since none of the doctors bother to mention their mentors, the ur-guru award goes to Rudyard Kipling’s 1901 Kim. While no superhero, Kim is the prototypical colonial adventurer, and Kipling supplies him with his very own “guru from Tibet,” one who conveniently needs an English boy (for some reason Asian kids won’t do) to achieve his life-long spiritual quest. Kim in turn treats the guru “precisely as he would have investigated a new building or a strange festival in Lahore city. The lama was his trove, and he purposed to take possession.” Which soon became official policy for all aspiring superheroes trawling the Orient for superpowers. Kim and his guru even prefigure Batman and Robin—only reversed, since Asian mentors are just like underage sidekicks.

Despite Kim’s Superman-like influence on the genre, even Kipling has his predecessors. The first superhero to pinch his powers from an obliging Oriental is Spring-Heeled Jack. The masked Victorian used to leap through a dozen plays, penny dreadfuls, and dime novels. I like the Alfred Coates 1886 version. Jack’s dad reaps his fortunes in colonial India, and Jack returns to England with the workings of a “magical boot” that “savoured strongly of sorcery.” Jack “had for a tutor an old Moonshee, who had formerly been connected with a troop of conjurers—and you must have heard how clever the Indian conjurers are. . . Well, this Moonshee taught me the mechanism of a boot which . . . enabled him to spring fifteen or twenty feet in the air.” That old Moonshee (Jack must mean “munshi,” an Urdu word for writer that the Brits decided meant all clerks) is the first incarnation of Wonderman’s turbaned Tibetan.

The endlessly exotic Orient, the planet-spanning ring of Britain’s 19th century frontier. A superhero is the ultimate colonialist, seizing his fortunes in faraway lands and shipping them home to maintain his nation’s status quo, its global supremacy. It used to be the British Empire, then the American, but superheroes always serve as the imperial guard.

While Eisner’s imaginary Tibetan was handing out magical treasure in 1938, real Tibetans were arguing national autonomy with China and rights of succession with warring regents. Unlike Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, the actual Zoroaster did not declare, “God is dead.” He was all about exercising free will in the service of divine order and so becoming one with the Creator. I’ve not read any of his surviving texts, and I seriously doubt Nietzsche did either. I’ve also never set foot in Asia—though I did gaze at it from a cruise ship docked in Istanbul, and that’s a lot closer than most comic book readers ever get.

[For more on this topic, my related essay, “The Imperial Superhero,” appears in the new PS: Political Science & Politics, as part of an eight-article symposium on the politics of the superhero.]