This piece first ran on adjective species.

____________

PIES is Ian King’s first graphic novel, although he contributed a short comic – a small and meditative exploration on sleep – to the first edition of RRUFFURR. His RRUFFURR comic features the same hero and acts as an inessential mini-prequel to the richer and deeper PIES.

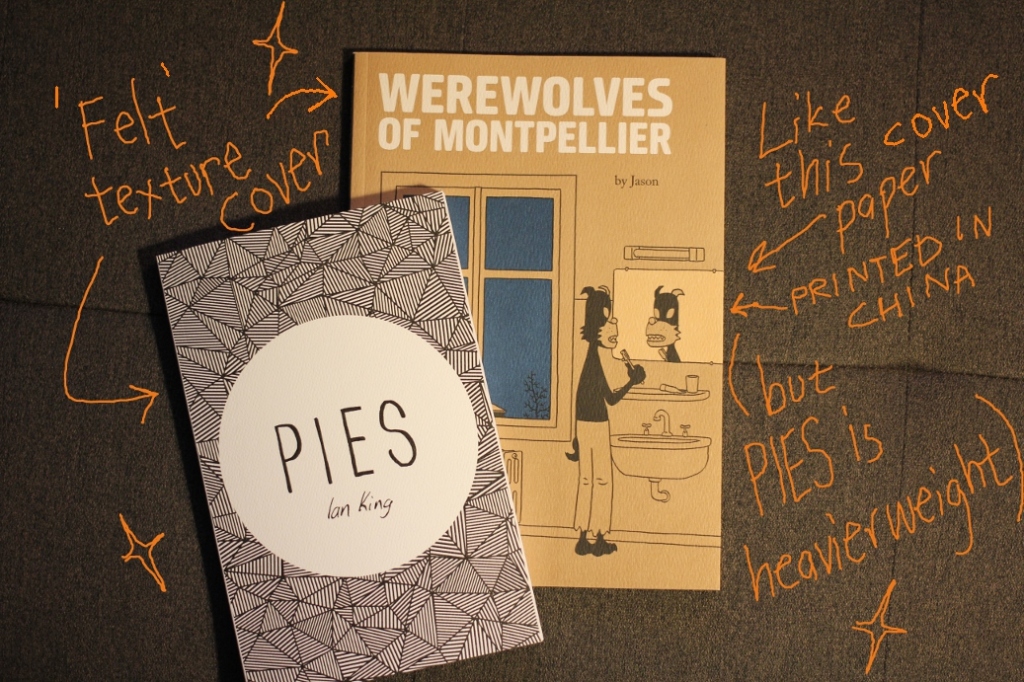

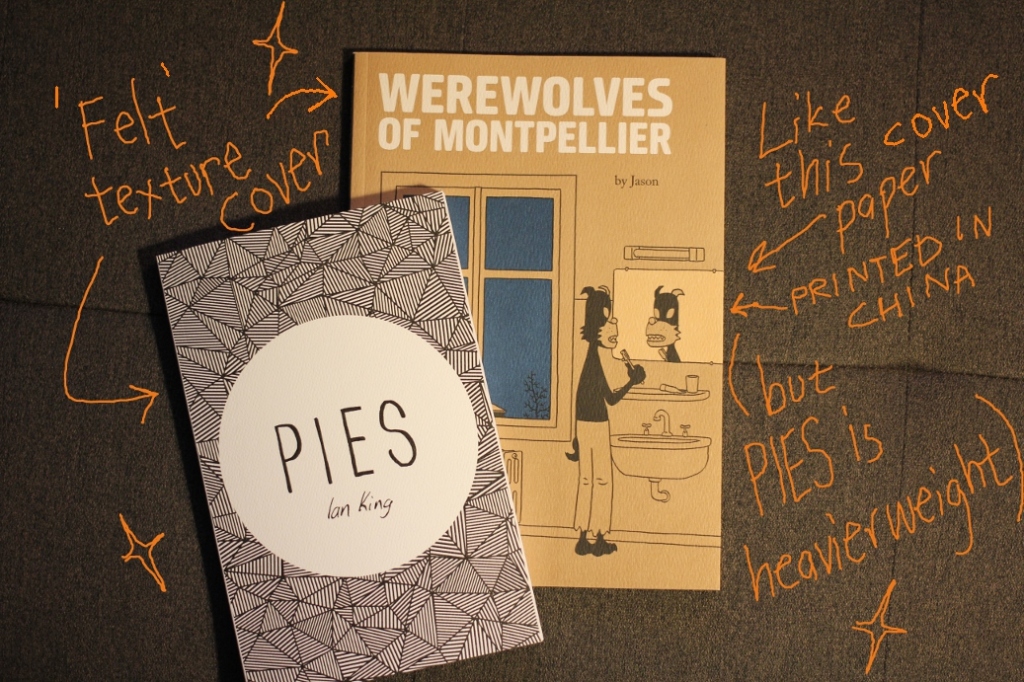

PIES is long at 114 pages, and completely wordless save for ‘PIES’, which is spelt out on the protagonist’s hoodie. It is available to read online for free and also in a high-quality print version, printed on heavy paper and bound in a textured cover. It’s well worth the $20 for a physical version.

For a debut, PIES is incredibly assured and nuanced. It’s clear that King has invested much time and thought into the editing and presentation, as well as the detailed illustrations. It joins the increasingly mature output from artists in the furry community, quality work that can stand alongside the very best of today’s independent graphic novels.

PIES follows our hero – I’m going to call him Pies – on an allegorical journey, that starts when he hops into an inner tube on a beach. He drifts away, and for the remainder of the book he has little or no control over his destination. Like the ageing process, where we all get older one day at a time regardless of our actions, Pies floats along towards his unknown but certain destination.

I showed PIES to a furry friend of mine recently, who remarked that he didn’t realise he’d need his ‘2001: A Space Odyssey brain’ to follow the story. It was a comment made in jest but it gives you a good idea of what to expect. PIES is abstract and wilfully obscure at times, but like the final third of 2001 it’s clear enough that our hero’s journey is a metaphor for his own life.

The torus of Pies’ inner tube is a recurring motif in PIES. Each torus represents a moment where his journey will forever change, a point of no return. This reflects the entropy of life, where we exist in an unchanging world until suddenly we don’t: when we turn 18 and become a legal adult; when we get married; when we hurt someone; when we have children; when we are diagnosed with a terminal disease. Pies’ world changes irreversibly when he reaches these waypoints, and while memory can conjure up images of the past, we must move on and exist in the world as it is now.

This is well-trodden ground, but PIES stands out by exploring this journey in an unusual way. Pies is alone, but PIES is not about loneliness. His journey is that of his life, but PIES is not about ageing or the transience of youth. PIES is, instead, about the greatest experience that life has to offer: love.

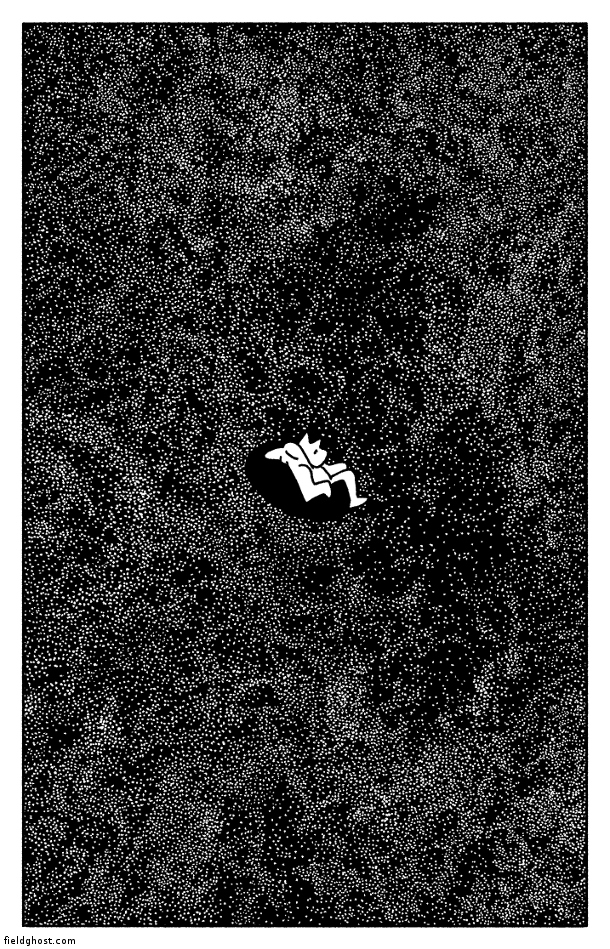

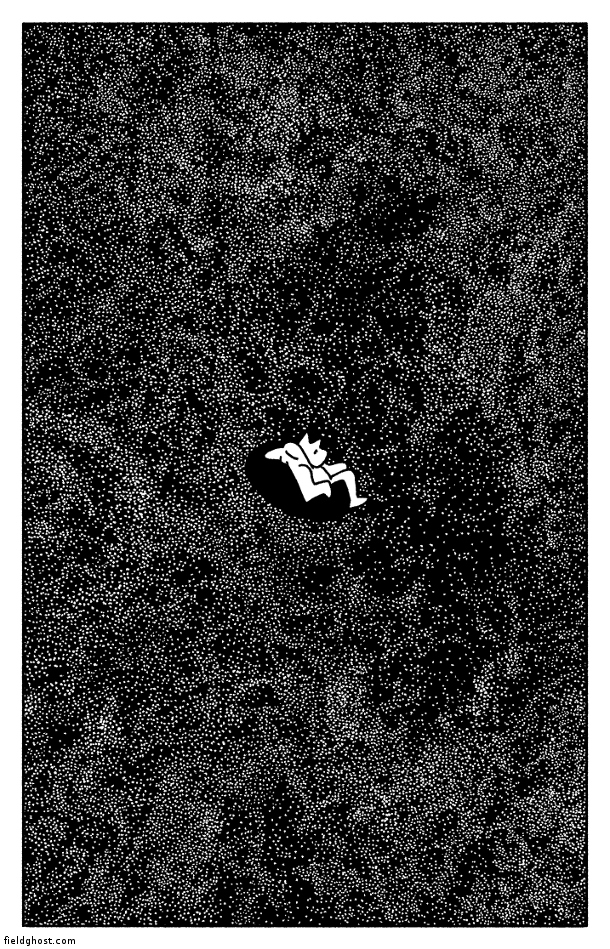

Pies carries a love note through his journey. In an early, sublime sequence, Pies drifts off to sleep while gently floating down a waterway. The sun has set, and the points of light reflected in the water become confused with the stars in the sky. As he falls asleep, the points slowly grow and morph until they crystallize into an endless sea of faces. For a moment, in his dream, Pies becomes one of those points of light: part of a community, a group of people (well, animal people) who are all experiencing their own journey, together alone.

There is peace and fellowship in the shared experience. Pies and everyone else are each drifting along in their own way.

In the next panel we see Pies’ lover, clutching the same love note, drifting along a different waterway in a different vessel but looking up at the same sky. It’s clear that the two of them share a close bond, and in Pies’ dream, the connection they share seems real and tangible. Their love is something Pies carries with him in his heart, as represented by the note itself.

Love is so close to a palpable presence, you sense it must be physically real. It can be expressed through a lover’s touch, but that’s just a fraction of the full feeling. The touch of someone you love is merely the sweet cherry on the substantial cake.

Think now, reader, of a loved one: a partner, a relative, a friend. Notice the physical sensation, not of their body, but of their essence. You may feel bereft, as if there were something nearby that you need. Yet the sensation is simultaneously tantalizing and fulfilling.

We lose our loved ones as we go through our journey. People die. We move. We break up. We drift apart. Yet the feeling of love is still there, ready to be conjured again and again, tinged with the bitterness of grief for what we have lost. But grief is not sadness. Grief is a close neighbour of joy, the joy that we would feel if we could see someone we’ve lost just one more time, the joy that we feel when a loved one walks into the room. Grief is the knowledge that we will never again feel the love without also feeling the loss.

But we will lose them all, eventually.

Pies will not see his lover throughout his journey, outside of his dream. But Pies carries his love everywhere. His last act, as he eventually is pulled down under the waves, is a defiant, celebratory fist in the air. A fist containing his lover’s note.

As well as the story of Pies’ journey, PIES is a formidable technical work of art. Geometric shapes and mesmerizing organic patterns appear and reappear, collapsing and coalescing through the story. It’s a book that deserves to be experienced on paper.

You can buy PIES for $20 if you are in the United States here (https://squareup.com/market/Pies), or here (http://pies.bigcartel.com/product/pies) for everyone else.

You can also read PIES online for free at fieldghost.com.

***

The relative anonymity of Ian King and PIES within the furry community is a bit of a puzzle. It is a major, meaty, immensely enjoyable animal-person graphic novel.

The high-profile artists who produce well-regarded works of art within furry tend to be technically accomplished. However their works, while pretty, are often artless beyond the illustration skills. That’s not to say that popularity isn’t deserved, just that more intellectually complex works like PIES rarely seem to attract much attention.

Furry graphic artists are taking advantage of an old trope, the use of anthropomorphic characters as a frame for exploration of the human condition. Animal-people give the artist freedom from the constraints of the real world, which means they can engage in flights of fancy without any implied requirement to adhere to the laws of physics and nature. In many ways, this is what we furries are doing in our lives: by adopting an animal-person identity, we are freeing ourselves from mundane social mores, making it easier to explore our own path with less pressure to conform to the mainstream. (As in: “hey I’m going to roleplay as gender x while being attracted to gender y, because let’s face it, it’s not that weird if you consider that I’m already an animal person”.)

The furry community is spoiled for riches when it comes to graphic novels and comics exploring these ideas – be they intellectual like PIES, or whimsical like Clair C’s works. These graphic novels and comic strips are rare examples of furry artists producing world-class works.

On release of the physical PIES book, King compared it to Werewolves of Montpellier, an acclaimed graphic novel by Norwegian artist Jason. The two books are very different in many ways – PIES is joyful and abstract; Werewolves is maudlin and direct – but the comparison feels apt. They are both complex works of art that rely on a world populated by animal-people to tell a story with an undercurrent of emotion and with minimal dialogue. The animal-people are essential because they prime the reader to trust the artist to maintain the internal logic of each story, without worrying about the ways it deviates from reality. Both books deserve a wide audience, an audience that PIES has not (yet) found.

The group of furries producing high-quality and serious graphic art is growing. RRUFFURR collects short pieces from several artists and accordingly feels like a great introduction. But I don’t really know where to go from there. Is there a hub for publications from our promising artists, collecting amateurs like Redacteur and professionals like Artdecade? Does someone have a carefully curated Tumblr follow list?

In the meantime, take a look at PIES. It deserves to be shared and read and cherished.

______

Follow Matt Healey on twitter @jmhorse.