I came to Brandon Graham’s Multiple Warheads by way of the Best American Comics 2014 collection and so I was unaware, when I began reading, that it had started life as a sex comic. It came as some surprise, then, when, after around 200 pages of visually packed images, surreal Soviet landscapes and cheap but charming puns, I turned the page to find images of the main protagonist, Sexica, having a large phallic object inserted into her anus, attaching a werewolf penis to her boyfriend, and then having sex with him while he transforms into a wolf.

None of this was entirely without precedent in the chronology of the collected edition – that the main characters enjoy an active sexual relationship is apparent throughout the story. On several occasions they are shown either in bed or lounging around in states of undress and on two other occasions we see the main couple engage in sexual activity.

However, on these occasions, as Eric Mesa argues, Sexia is not drawn as unrealistically proportioned, and the sexual acts depicted (including cunnilinguis) are as much to do with female pleasure as male desire. I would not describe the comic as a shining, or even good, example of pro-sex feminism (if such an ideal even exists) because Graham also consciously presents Sexica as erotic spectacle (at one point he reflects on a 2007 comic ‘I sure drew a lot of butts’). I don’t see the comic as particularly feminist, but I can at least understand Eric Mesa’s argument.

The sex comic, therefore, was not a complete thematic break, but it did run counter to many of the representations of sex and gender in other episodes of the comic. It reverses all of the points Mesa raises. Sexica is drawn with exaggerated proportions. She expresses her discomfort at being anally penetrated and is told that this course of action is better because her unnamed smuggling contact gets to ‘shove it up your butt’. The smuggling contact gives a satisfied ‘Heh’ upon successfully penetrating her. The following series of panels seem to take gleeful delight in depicting her walking with discomfort.

The male gaze is also given more explicit form; when Sexica passes through the security scanner the x-ray labels her body parts ‘tits … ass … leg… leg’ and informs anyone looking at the scanner that her breasts are unevenly sized. This image breaks a female character into parts and presents the male gaze as objective. In sum, the sex comic is problematic not only because of its use of the female body, because it undermines the potentially positive readings which rest of the comic might elicit.

This mix of misogynistic humor and cartoonish eroticism was punctuated, bizarrely, by several overt references to the September 11th terrorist attacks. As the object is fully inserted into Sexica’s anus the sound she makes is represented by an image of the second plane about to hit the Twin Towers.

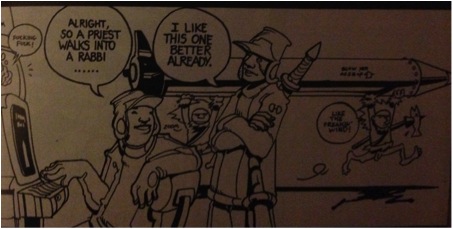

Later, two security officers monitoring an x-ray scanner are too busy sharing jokes to notice, first, that Sexica is smuggling an illegal item inside her body and, second, two men carrying a comically large explosive device labelled ‘blow yer ass*up’.

I understand what misogynistic erotica was doing in the comic, but why the references to 9/11?

I really don’t know what is happening here, but I have a few ideas. My first thought is that the (perhaps inappropriate) connection between sexual and territorial violation with regard to the September 11th terrorist attacks is well-trodden ground. In Sam Glanzman’s short comic ‘There Were Tears In Her Eyes’ for the collection 9-11: Artists Respond, one character (problematically) compares the destruction of the Twin Towers to the Statue of Liberty being raped. Tonally, however, Multiple Warheads has little in common with the theme of mourning in the 9-11 collection. If anything, Graham seems to engage with what occurred using a discordantly light-hearted register.

This, in itself, could be read as a way to manage one’s fears by parodying them. Graham is a New York resident and, while we cannot presume to know how he was personally affected, I think it is reasonable to assume that it had some impact on him. Perhaps transforming trauma into something visual and tangible, even darkly humorous, is a way to reduce and contain it?

Conversely, the handling of the September 11th terrorist attacks might be read as a tribute to the taboo-breaking which characterised the Underground Comix movement of the 1960s and early 1970s. Underground Comix were, broadly speaking, designed, among other things, to offend the sensibilities of white, hawkish, church-going Americans. Many artists used their medium as a means to give shape to their darker fantasies simply to draw the most violent and depraved acts they could imagine. No topic, however taboo, was off limits. As Sabin argues ‘the comix revelled in every kind of sex imaginable [and] took bloodshed to extremes’ This openness, inevitably, spilled over into misogyny as the genre’s commitment to bearing all positively embraced political insensitivity – if you were offended, Comix declared, that was your problem.

If read as a stylist continuation of the Underground Comix genre, we might therefore understand this episode of Multiple Warheads as designed primarily to test and outright violate boundaries of good taste. The taboos of crypto-beastiality, sexual violence, and of making light of national tragedy seem all to exist within a continuum.

These are all just guesses, though. I am still baffled by the mix of cartoonish eroticism, grotesque and misogynistic humour, and national trauma, and perhaps my theories are just me trying to make sense of something which was never meant to bear analysis. I would be interested to know how others read this.

I haven’t read this, but if I had to guess, Underground Comix sounds like the most likely explanation. That’s a genre that has a lot of momentum I think.

I find it makes more sense to situate the work within his porn comics rather than attempt to graft it onto his non-porn work. Porn is always going to be a mixture of things that defy various taboos for the sake of titillation. I don’t think it’s useful to examine porn the same way as you would examine non-porn work. As you can see here, it just leaves you baffled–because you’re trying to reconcile things morally that work fundamentally because they are taboo.

I think a formalist analysis yields better returns when it comes to porn.

Hi Sarah,

Are there particular works of scholarship you would recommend as a good starting point when discussing this kind of material? I was a little unsure when writing this post because this is was my first encounter with a sex comic and (as you can see), I really wasn’t sure how to approach it.

I’m not sure I agree that porn shouldn’t be discussed in terms of content… Linda Williams’ “Hard Core” is an interesting discussion of porn films which is focuses on gender issues, mostly. It’s very good. Anne Allison’s Permitted and Prohibited Desires does interesting readings of some 80s porn manga. There’s been a fair amount of scholarship on Boys’ Love and Yaoi I think…

Thanks for the recommendations, Noah. I will check those out.

My biggest problem with the book has always been the decision to print the stories out of order. If taken in order, it becomes a meta commentary: what happens to characters from a porno after the pornographic episode is over? The characters go on with their very interesting and dynamic and complex lives.

“Multiple Warheadz,” the short story was a one-off pornographic story that Graham submitted to a pornographic magazine. The year was 2002 and 9/11 was a fresh wound for everybody. An anxiety that worked its way into culture immediately and on every level. Even me, I’ve always thought of the summer of 2001 as “The Last Good Summer.” Anyway, 9/11.

This comic, “Multiple Warheadz,” was just a sex goof for a porn magazine with the author’s post-9/11 anxieties mixed in. It could have remained that simple. But somehow he had the idea to investigate these characters, mine their depths, expand on their lives and world. From a strange starting point grew one of the wildest, most interesting comics series.

It’s totally understandable that the initial standalone story would be offputting, disconcerting or offensive to some, given its origin. But having the first story included in the collection draws a direct line between the more radio friendly Multiple Warheads and the grungy underground Multiple Warheadz. It’s all part of the same thing, and as we see in this collection, a thing can change over time.

Hi Ayo,

Thanks for giving the year for the original piece. In 2002 the immediacy of 9/11 was very apparent, although I am still not sure exactly what purpose it serves in the sex comic aside from taboo-breaking.

I can understand why the collected editon has the sex comic as an appendix – the comic that does open the series gives a more intelligible introduction to who the characters are and is more in-keeping with the rest of the book. Perhaps an introduction would have been helpful because, without doing research I would have had no idea about the history of the series.

I’d hesitate to chalk the 9-11 stuff up to taboo breaking in the underground tradition. It seems a bit understated for that. I read it as a flourish consistent with the book’s tonal commitment to the ridiculous and the sublime.

Sarah expanded on her discussion here.

The assumption seems to be that the main purpose of porn is to turn you on, which…possibly. Linda Williams kind of argues that that’s not the case, and certainly it wasn’t exactly the case for de Sade…There’s a lot of writing on de Sade discussing his ideology, etc. And on Masoch too.

I think it’s kind of interesting that Sarah’s argument is that you shouldn’t shame people for porn, but she ends up somewhat harshly chastising Phillip for a pretty ambivalent and tentative post. Why is it okay to shame or censure someone for criticism rather than for porn?

I think porn does in fact often have ideology and meaning beyond just breaking taboos and getting people off. It’s an aesthetic endeavor, like any other art. As such, people can talk about it, either formally, or thinking about its meaning.

Ack, still thinking about this.

Sarah seems to be saying that desire is personal and idiosyncratic, solely. If that were the case, porn wouldn’t exist, because desire would be incommunicable. You couldn’t talk about it, and if you can’t talk about it, you can’t make art about it; art is communication.

But the truth is that desire is shaped by and shapes culture. Desire and pleasure are hugely important in terms of how we experience the world, and think about the world. And porn has historically recognized that in lots of ways. There’s lots of explicitly ideological porn (feminist porn, for example), and porn that plays with tropes, or porn that is satirical, or what have you. I think separating porn off from art is more stigmatizing, not less. Recognizing it as a shaped artistic endeavor, rather than as some product of the id that can only have one meaning (taboo breaking, or what have you) seems like an insult to folks who make art with sexual content.

My book on Wonder Woman is essentially all about porn, now that I think about it. Marston/Peter’s comic was very focused on Marston’s fetishes, and was about being sexy and staging bondage scenes (and mind control, and foot fetish, and…) But that doesn’t make it more private; in Marston’s view talking about desire had universal implications and resonance. And I think he was right.

seems like an insult to folks who make art with sexual content. – See more at: https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2015/07/sex-comics-and-911-in-multiple-warheads/#commentspost

Art with sexual content is not always porn. An essential part of porn is that it turns someone on otherwise it is just art with sexual content. Not saying you can’t critique it but the turning people on is part of what it is. It is like if I am chief art director for the American Phrenology Association, and if my posters don’t drive traffic to my worthy cause then at some level it failed but we can also look at them from other angles.

For me the question I guess is more what is the threshold for turning people on. With 7 billion people, someone is probably turned on reading The Economist but I wouldn’t call that porn. Not saying this take isn’t a mess but I still get back to the essential element of turning people on.

My concern (and I am guessing shared by Sarah) is that what can we say about the character of someone who is turned by X, particularly if X is something that someone generally doesn’t feel represents them except in this narrow response. I don’t think you can conclude much at all about what type of person is turned on by X but it is interesting. I imagine what turns people on is a complicated mix of factors but no evidence to support that. People do look at how sexual orientation impacts your life

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/gay-and-lesbian-well-being/201108/gay-men-and-their-mothers-is-there-special-closeness

P.S. I have no formal association with the American Phrenology Association if such an entity exists.

“the turning people on is part of what it is”

All genre descriptions are porous and uncertain. Different people are turned on by different things; creators have different intents. I’d say the original Wonder Woman comics were definitely intended by Marston to turn himself on. Does that make them porn? Most people would say not; they’re kids comics.

I think it’s generally a bad idea to say that a certain genre has to be critiqued a certain way, in part because there aren’t any good definitions of genre, so critical discussions just get bogged down in pointless arguments about whether something fits an arbitrary definition. Porn’s just an art genre. People’s pleasures are always kind of nervous and embarrassing. But art, all art, invites a range of responses. Sometimes fans of certain porn may bristle if a critic has a reading of a work they don’t like. That’s true of readers of Harry Potter and romance novels and Shakespeare too. I don’t see porn as being especially different, in that regard.

This article — which I quite enjoyed — inspired me to tweet. :)

Honestly, *most* visual artists have produced art that is undoubtedly “pornographic”– including Durer and Manet, who I also tweeted about in this vein, and John Waters, my love! And Flaubert’s bestial couplings! (swoon). It’s really a question of context and critical approach. But as pertains to sexual acts and the intent to turn someone on, art is supposed to move us. The idea that moving us in a sexual way is somehow dumb or uncritical is, imo… dumb and uncritical.

And finally, as pertains to the common defense of Sade as so pornographic, violent, and almost Rabelaisian, that no one can get turned-on. Ha! I think that *is* a nod towards respectability politics, and I think it’s untrue. That goes for Klossowski, Bataille, Rabelais, and all those other raucous perverts. In my experience and those that I have spoken to about such things — and I have, actually — well, we’ve all gotten turned on at precise moments despite ourselves. With that said, my own fantasies are in no way “sadistic,” generally. But there is always a spectrum. Or even better: spectrums.

Anyway, just my two cents…

I wouldn’t argue against most of the sexism apparent in this particular MW story. However, I believe that the tastelessness of the 9/11 references are overstated, or at least the author’s reasons for finding them tasteless are understated. The “word balloon” featuring the twin towers shows that Sexica feels (whether or not she’s expressing this with sound or words) that getting a werewolf dick shoved in her ass is comparable to 9/11. This seems to me not to make light of 9/11, but to make light of the pain she’s in at that moment. It’s very common to use this sort of extreme hyperbole to make personal pain more tolerable; think of someone yelling “Jesus Christ” when stubbing their toe, as if such a minor injury were comparable to being crucified or worthy of an appeal to a higher power. Even if this could be somehow construed as a mockery of 9/11, I would argue that it is a mockery specifically of the sensationalization of the event, which has been used truly tastelessly to promote wars and t-shirts. Even then, it is hardly the point of the gag; it’s only a clever way of communicating that she’s in pain. (Incidentally, the author implies that there is misogyny in the depiction of Sexica’s discomfort, disregarding the fact that many people consensually experience such discomfort in sexual circumstances; if her consent is not made explicit here, let’s remember that this is a fantasy, and dreamers of sex fantasies often invent scenarios wherein their own consent or the consent of others is not necessarily explicit.) If the x-ray scanner scene is construed as a reference to 9/11 (and it’s worth noting that x-ray scanners were not present in airports until years after this comic was drawn) and is additionally construed as a mockery, then it is a mockery of the TSA’s incompetence and disrespect for personal privacy, which I’d argue is fair game. It appears to me that the author has taken for granted that these references to 9/11 must be a joke at the expense of its victims and all those affected directly or indirectly by it, and I think more needs to be said to prove that point.

As an aside, I’d like to call into question the fallacious way the author connects this comic to the 60’s American underground. Anyone who’s followed Brandon Graham at all on social media can surmise that his main enthusiasm is for 80’s and 90’s European and Japanese comics, along with western independent sci-fi comics that bare little resemblance to the work of, say, R. Crumb (who Graham has explicitly expressed having little interest in). To say that Graham is directly “paying tribute” to 60’s American underground comics just because his work may be the slightest bit crass betrays a grossly oversimplified understanding of comics’ history. More regrettably, it implies that Graham must have the same aims as those “taboo breakers” and is thus complicit in the same artistic crimes, simply because of the shaky connection drawn by the author. It’s fine to just call the comic offensive; the elements of the work are there and it’s your job to figure out what they’re doing; it’s not your job to presume influence or intent. (Or maybe it is, but God, what a boring job if that’s the case.)

So, bmfu, your points are interesting ones. However, your aggressive defensiveness seems a little overblown? Phillip explicitly says, over and over, that he’s not sure what to make of the comic,and asks for input. He doesn’t say, “this is an underground comic!” He says, maybe it’s influenced by underground comics…maybe not…he’s not entirely sure.

Figuring out influence and intent is in fact often an important part of criticism. It’s not boring; thinking about art in relation to other art is part of enjoying and thinking about art (for me, and for many other critics.)

I think it is useful to look at Graham’s named influences in charting the genealogy of his work, and I think if I had known that he has explicitly stated his not being interested in the Underground that might have changed my reading. On the other hand, there are genre markers which remind me of the Underground beyond just the cartoonish erotica and transgression; the font which reads ‘FUCK COMIX’ in the final panel, for example, reminds me of Spiegelman’s very early work (not to mention the spelling ‘comix’). Whether Graham intended it or not, there seems to me to be a bit of the Underground in Multiple Warheads’ blood.

Regardless, as Noah says, I am not trying to push a single reading, and if the Underground explanation does not hold water then that at least helps us understand what is happening here by process of elimination.

I should perhaps clarify that I am not personally offended by the 9/11 references, although I can certainly see how someone who was directly affected might be. I am just curious what they are doing there. So far, I think the most compelling explanation I have seen here is from Ayo, who sees it as a way for Graham to play out and diminish his post-9/11 anxieties.

I think discussions of influence are always about the people having the discussion, not the actual artist. Unless you can read Brandon Graham’s mind, you have no idea what his influences are. All you are doing when you talk about influence is imposing your own experience and calling it his. There’s an infinity of influences in any singular piece of art, from artists you know, artists you don’t, to grade school teachers. Nothing is 1 to 1. I don’t find it fruitful at all, as a critic. And I find that it distorts the work, by forcing you to see work through one particular influence versus any other. It adds an unnecessary lens.

But it doesn’t force. Art does have influences, codes, references. And the work must necessarily be distorted by the viewer anyway.

Whether influence is a good lens depends as much on how it’s used as it does on who’s using it… If the critic is merely playing “spot the influence” then, yeah, it’s unnecessary. However, a lot of art, including (and maybe even expecialy Graham’s art) is in conversation with its influences and inspirations.

Sarah, do you think of criticism as art?

Because you seem to want to privilege and protect artists, but you have a whole list of quite strict, arbitrary, and often openly censorious opinions about what critics are and are not allowed to do.

If you don’t want to write about influences, and don’t want to think about content in porn, by all means, write about other things. But it’s not freeing artists to attack and denigrate all critical approaches other than your own. On the contrary, it’s restricting freedom of expression of those artists called “critics” (who have been around longer than comics creators, for what it’s worth.)

Criticism isn’t there to flatter the artist, or really to understand the art, any more than art is there to flatter reality, or (necessarily) to understand it. Criticism is its own aesthetic object. If someone thinks it’s interesting, or beautiful, or fun, or meaningful to link an artist to possible influences or to other works, who the hell cares if it’s more about the people having the discussion than the artist? Why should this artist doing comics be more important than that artist doing criticism? You write about how you’re worried that discussing porn will be censorious or will shut people down, but then you turn around and eagerly advocate shutting down all kinds of conversations just on the grounds that they don’t interest you.

Re influences in particular. Of course you don’t know for certain anything. But when Ta-Nehisi Coates writes a piece based on The Fire Next Time, thinking about his relationship to James Baldwin seems like a reasonable thing to do (if you’re interested in James Baldwin.) The Underground has an aesthetic and an influence that is worth thinking about and contesting. Artists aren’t isolated geniuses spewing formal brilliance onto the inside of a box. They’re communicating with an audience, with the past, with each other. Which is what I find exciting about art, myself.

Also, spot the influence can be fun, damn it. “hey, this person loves the thing I love” is a totally valid response to a piece of artwork, it seems like to me. Somewhat fannish, maybe, but that’s not always a bad thing.

I don’t even think it has to be overt as in the case of TNC and Baldwin. Sometimes, comparing artists and works tells us something about the history of thought and/or myth.

For instance, and tangentially — but Sade’s been discussed and this is a mere aside for anyone who is interested in art/porn/politics — I am very much convinced that Sade’s Justine and Voltaire’s Candide are the same story told under different historical/cultural circumstances, although *only* about 30 years apart. Still, their differences also seem to be revelatory in terms of understanding the Enlightenment vs the Terror. I think this is rich territory.

Further, the criticism of a period very much reflects that period: their preoccupations, anxieties, elisions, etc. Much of the Sade criticism from French Existenitalists completely overlooks the fact that Sade wrote classically moral tales, as well, wherein he very overtly warned against the dangers of libertinage. Why would they overlook this? (I don’t know.) But fwiw, my favorite essay on Sade is by Jean Paulhan, “The Marquis de Sade and his Accomplice.” I know this is tangential, and my appologies. But it is such a beautiful and sensitive essay. :)

And as to Noah’s last comment — Yes. Very fun! But also, these references and influences (sometimes quite overt!) offer a subtext and/or internal dialogue/tension within the work itself….

Not to disagree Noah, but isn’t criticism at heart, a search for truth?

(And clearly enough HU, at its heart, is about criticism.)

When I talk about criticism, I’m talking about what approaches are useful, and what approaches are not. I’m not making a moral judgement or saying you can’t do this or can’t do that. When someone writes about influences in a piece of art, they are functionally writing about the art they are superimposing upon the work. They can do that, but I don’t find that kind of criticism useful, interesting, or “fun”. I find it self-serving, laborious, and obfuscating.

Do I think criticism is art? No. I think art can criticize, but I don’t think criticism in and of itself is art. It is almost by definition not art. Unless you want to just call everything in the world that has ever existed art. Which given your opinions on genre, I’m sure you do.

For me I value clarity in that kind of writing, because I feel that criticism can be enriching for people to read or listen to, and it can teach them how to see art. But I obviously have opinions on the approaches which I find serve others vs. approaches that serve the ego of the critic.

My goal as a critic broadly speaking is to try and bring people closer to the art, and I generally refuse approaches that prop up lenses between people and art, and present the critic as a kind of priest class. What I try to do with my criticism, by sticking as close to the text as I can, is show that it’s all there in the art already, that you as a viewer, don’t need all of this excess information–you can see and experience art powerfully simply through your skills as a thinker and an observer.

When I write serious criticism, my goal is is to teach my reader how to think for themselves. I don’t want them to see me as some great holder of information that they need but don’t have access to.

Now there is another kind of criticism that I will write, where I will use a piece of art to explain some sort of personal experience that I have through it, and the aim of that criticism is to get you to understand my reality better. But I consider that a lesser criticism, because it is not about the art, it’s about me.

And while it’s certainly true that everything is always about me or you–I feel that language is at its best when we have nearly agreed upon meanings, and then can use those symbols to build an imperfect bridge of understanding between two fields. I have no interest in the self-fellating mechanisms of post modern faux academia.

Which doesn’t mean you aren’t free to engage in it. But your church isn’t my church, and I will freely express that. And I openly explain why that is, with the most precise language I can muster.

“Truth” is a big word that I don’t understand in this context at all. What do you mean searching for “truth” in art(ifice)? There are interesting answers to this, but I think these answers are not in any way given. What givens are we all to assume or understand?

Sarah: You won’t recognize discussion of artistic influences as “useful” but you accuse other critics of self-felating when they think of the arts in communication with themselves? Is art supposed to be “useful”? What does that mean? Do you believe that an art reveals itself within itself without reference to any outside trope, narrative, myth, etc? How do you think symbols work? I honestly do not understand.

Sarah, the “church” language seems telling. You’re an evangelist, which is to say an imperialist, in the name of freedom. Which seems contradictory to me. If you don’t want to talk about influences, don’t talk about them. But if the point is that art is self-contained and not a conversation, then why on earth does it matter to you *how* I talk about it or don’t? Why the need for churches. Seriously, I have no problem with formal crit; even write it sometimes. Why does all the criticism need to be your criticism if we’re to have freedom? And where does this utilitarian language come in, anyway?

The argument that criticism isn’t art is I think pretty thoroughly unsustainable. Keats’ criticism isn’t art? Virginia Woolf isn’t creating art when she writes criticism, but some piece of crap 70s superhero comic is art? James Baldwin’s The Devil Finds Work isn’t art?

What is art? Does it have something to do with beauty? with passion? with meaning? How would criticism not qualify there? Or is art only the genres you like, then?

You want criticism to show that there is no need for criticism. To me, it seems like your artistic project should then be not to write criticism. Any truth you show through criticism is going to be mediated. You claim there’s some way to get yourself from out between the viewer and the art, but if you want to not be there, why step in between? It doesn’t make much sense to me…though of course that doesn’t mean that your art of criticism can’t be worthwhile in its own right. Art is often self-contradictory.

I can’t say I understand why people are automatically less important than art. Art can be great, but people can be too. A personal essay isn’t “less” than a painting, unless you think painting as a genre is automatically better than personal essays. I find that kind of privileging of particular genres reductive and impoverished…but it is the way a lot of people approach art, I’ll admit.

BU, criticism *can* be a search for truth, just as art can be, but it doesn’t have to be. Criticism can be polemic; it can be performance; it can be about beauty, or just goofing around. Different critics have different goals and different muses, just as different comics creators do.

Anyway…the fact that Sarah doesn’t see criticism as art is the crux of the matter. As so often with critical discussions, it all comes down to genre distinctions. More evidence that genre is the broader category and comes before art.

“More evidence that genre is the broader category and comes before art.” Oh wow! That’s really interesting. :)

Hah…I fear this will irritate Sarah if she’s still reading…it’s an insight from Carl Freedman’s wonderful book Critical Theory and Science Fiction. He points out that we designate genre before art. For instance, laundry lists are not art; they’re in the wrong genre. Poems are because they’re in the right genre. So determination of genre precedes the category of art…or in other words, art is a genre, rather than genre being a subsection of art.

It’s interesting in thinking on art v. craft (and class), as well. I’ll check out the Carl Freedman.

It’s such a great book. Lovely readings of the Dispossessed and The Man in the High Castle, among other things.

i just find the continual reference to the subject as “a sex comic” off-putting.

Hi mouse. Any chance you find sex off-putting? I ask not because I expect an answer, but because “sex” as a modifier seems to upset people in interesting ways: sex work, sex(ual) assault, sex education, sex toys, sex comics, etc., which leads me to believe that sex is the stumbling block somehow.

So, I’m just trying to figure out why a culture that is strung out on “sexy” is put-off when sex is a main (conscious) theme.

It looks like a huge part of this conversation took place while I was asleep, but, to chime in. When done in a (to use Noah’s term) ‘spot the influence’ way, intertextual criticism can be very pedestrian and add little to our understanding of a text, and I can completely understand Sarah’s dislike of that kind of scholarship. Conversely, I think that the kind of criticism which asks not only how the text resembles other works, but, more importantly, how it deviates and why can be highly illuminating (I am thinking, in particular, of some of the excellent work done with Shakespeare’s sources). In fact, some works, like Joyce’s Ulysees, are designed to be read in relation to other texts and to look at them in complete isolation is to miss a large part of what the author is doing.

1. I think Sarah has the problem with explicitly framing the work of Brandon Graham with the frame of the underground comix movement (and Sarah herself has written a great cohesive essay on Brandon’s work here https://mercurialblonde.wordpress.com/2013/02/24/atrocity-exhibition-first-draft-3000-word-sprawl-reaction-to-brandon-grahams-multiple-warheads/), which is like framing Joyce as a ‘naturalist’ just because he apparently happened to write Dubliners before his magnum opus. That’s where the ‘finding of links’ gets tenuous and, quite frankly, misrepresentative of what makes the author great. You’re framing Brandon Graham, who draws like 500 things per page, and makes such expansive fantastic worlds, into the frame of a single movement due to some subversive sex comic that happened to be the precursor to his project. Yes Joyce also does have a naturalist tinge in some areas of Ulysses, but you get the tenuousness of the ‘influence’.

2. There’s always a way to point out the ‘correct’ influences, or to weave all these slightly disparate literary universes into one another, like say the approach of Borges when he’s writing his criticism. He approaches influence density in his writings, so it seems as if he’s making a whole scope of human history whenever he reviews, but Borges will never ever make the mistake of conflating one of his proper fictions with that of a review. Even in his ‘fictional reviews’ those are chased more like highly intellectual philosophical pieces. He saves the mind for the short story, and the heart for the review, but in the framework of Borges’ aesthetics, which is primarily of the mind, the heart is always a lesser entity.

3. No writer wants to really be merely a ‘critic’, because he sees the process of commentating on others works as merely a stepping stone in his own creative endeavors. (of course I can tell you’re gonna throw the counter examples of weird people like Nabokov, or Derrida’s Glas, who somehow makes ‘critic novels’, but then again it is the writer integrating criticism, not the criticism integrating the writer. Derrida’s project is still disparate from his weird experiments, and Nabokov had to write the poem he himself ‘critiqued’.) The writer who wants to claim his criticism is art, generally doesn’t have art himself to speak of. Noah’s examples are undermined by the fact that Woolf and Keats never wrote those with the intention of making them ‘art’ in the same way they focused their intentions on their actual works themselves. If you went to Woolf to say that her diaries are better than her books, don’t you think she’d be slightly miffed? I’m not saying that there are instances where the side-writing doesn’t sometimes overshadow the main, but at least no artist would want to know that its his destiny to play on the sidelines of his own artistic projects.

4. Likewise, for Sarah, who is an artist, the same applies. She finds no interest in criticism that seeks to be ‘academic’, that communicates no formal framework except for a mere series of tenuous interpretations (because anything that isn’t formal isn’t of interest to her art), and most importantly, never communicates anything of deep confessional subjective feeling on the side of the author himself or herself, to the reader. I mean you’re trying to argue for the idea that criticism is art when the above piece blatantly doesn’t aim to be so, it sounds like an abstract attack with marble to protect the dignity of a stone.

“No writer wants to really be merely a ‘critic’, because he sees the process of commentating on others works as merely a stepping stone in his own creative endeavors”

You don’t know what you’re talking about.

James Baldwin’s criticism is supposed to be art, and is art. Also happens to be better than his novels. And then there’s people like Zizek… And I wasn’t talking about Woolf’s diaries. She wrote criticism. Including “A Room Of Her Own,” which I suspect she’d be happy to claim as a major work.

And you know…I’m an artist. (Hello!) Criticism is the main (though not the only) form my art takes. Maybe it’s bad art! But art is what it is, good or bad.

Now people will say, “oh it’s all about you.” But of course comics has a long tradition of fighting to be recognized as art…which I believe is part of what is actuating this thread. Criticism has been around longer than comics, and as an aesthetic genre (and really often incorporated into art and artistic practice, as Borges and Nabokov demonstrate.) It’s a genre people often don’t like or resent…but art isn’t always supposed to make you comfy, in my view.

” I mean you’re trying to argue for the idea that criticism is art when the above piece blatantly doesn’t aim to be so, it sounds like an abstract attack with marble to protect the dignity of a stone.”

So…art can’t be tentative, and has to be confessional, because…reasons? Phillip’s essay is not super ambitious, but art doesn’t have to be extremely ambitious. And I know you’re saying all this re: Sarah’s art…and I’m happy to let Sarah’s art be Sarah’s art. I object to Sarah making sweeping declarations about how everyone else is allowed to do their art in the name of some sort of supposed defense of artist’s integrity.

And Phillip didn’t frame Graham’s work in terms of the underground. He suggested you might possibly do that. Which doesn’t seem like an especially aggressive thing to do, to me.

(Edited out a little snark at the end.)

I don’t know how relevant this is, but I Googled “Brandon Graham, Crumb” and found this: https://twitter.com/royalboiler/status/509972116692017152 Does that strike anyone else as a weird reaction? I always think the piggyback thing is one of Crumb’s most lovable quirks. Anyway, Graham’s work looks great and I’d like to see more of it.

Criticism often seems like a lower form of art or quasi-art, and there is something off-putting about, say, someone who can’t draw at all sneering at the drawing ability of a professional artist. But yeah, I agree with Noah, criticism can do all kinds of things and at least some criticism is very good art.

hah…not sure it’s a weird reaction, but he is doing what Sarah tells people not to do in terms of shaming artists because they make unusual porn.

I think the crux of this in Horrocks’s assertion that a critic can teach a reader to think (about art) for herself. As someone who is both a critic and a teacher, I’d argue that this is almost impossible, as to teach a reader to view art is necessarily to provide the reader with a tool-kit comprised of lenses, and to choose the lens according to the goal of the critique and in good-faith.

I also take issue with the notion that one can make hard and fast determinations about what is or isn’t art given that art has been defined variously since before Plato, and since art criticism has existed alongside art and influencing what we see as art.

Honestly though, I’m being circumspect in my writing here because I’d hate to see this turn into an “Team HU” vs. “Team Horrocks.” As a reader of Horrocks, I think she does a good job of developing an argument about a comic’s significance through close attention to its formal features and by comparing it to other, similar work. I hope she sticks around the comment thread, and that there are more articles on HU about Graham’s work.

Of all the things to be creeped out by in Crumb, the piggyback rides would be my last pick…

Roland Barthes (who I detest with every bone in my body) had an idea that I’m quite attached to which he called: “write-ability.” These are works that destabilize the subject and create more works. They incite one to write, they create openings, and they need not be “perfect.” Indeed, they *cannot* be perfect or complete.

He covered it in the “Pleasure of the Text,” which might also add a layer to the porn/art distinction. There isn’t one, unless you assume the sexuality of the reader/spectator.

But just as Sarah asserted that the critic cannot read the creator’s mind, the inverse is true as well. Art is a conversation/communion, an ongoing process. It’s not a one-way street.

I’d love to see someone else write about Graham’s work, if someone’s up for it (or if Phillip wants to do a follow up…)

Apparently it’s the mark of postmodern amorphousness to reattribute signs and names to various other signs and names, in order to ‘designate’ something about the problems of communication.

Of course I understand the argument from your part, which is that any text contains aesthetics, and anything that has aesthetics can be represented as art, thus any text, regardless of content, can be represented as art. If you go by that context then anything has aesthetics, and thus anything can be art.

Likewise I believe in the project of Wittgenstein that we need demarcations in order to bring clarity to our intentions. These demarcations have to correspond as succinctly as possible to their usage, and if not then we find ourselves mis-communicating our various intentions and worldviews to one another, and sometimes we even make wrongful speculations on morality and metaphysics due to our usage.

I made the mistake in my earlier post of saying that the writer who claims to have criticism as art, generally doesn’t have art to speak of. This was miscommunicated as the proposition that ‘all critics, essayists, commentators, and their ilk, are not artists’. Of course if I go from your context, then you can just come up with any possible example of a pretty darn good criticism to refute my example. Let me refine the point a bit then. Instead let me change it to this proposition ‘all artists aim to imbue any text they create with aesthetics, and this includes criticism, essays, commentaries etc…and he who forgets aesthetics is immediately exempted from the realm of artistry’. This seems pretty self-evident right? Mainly that an artist has to care about aesthetics. He has to care about communicating a certain feeling or sensation to the reader, so as to make his work primary to the reader, despite being contingent on another frame.

Now going from that axiom, we can clarify the issue. Art refers to any work that contains aesthetics. Criticism refers to any work that is contingent on another work. The two realms have the possibility of intersecting, and thus criticism can have aesthetics, and thus can also be art.

But if we were to conflate the two so easily, then why even bother with the demarcation in the first place? Obviously we want to draw our attention to those areas outside of the intersection, that is of art without criticism, and criticism without artistry.

I’ve sought to prove a marker for what makes art, which is aesthetics, but I’ve yet to prove a marker for what makes criticism, actually criticize. A criticism is contingent on a work, and thus seeks to illuminate about the work. Normally this can come in the form of interpretation, formal analysis, autobiographical analysis (as in when you state what the work means to your own experience), or historiography. Horrocks usually writes criticisms that intersect formal with autobiographical. The above article is a matter of historiography with interpretation.

Now since aesthetics is contingent on feeling, its also extremely hard to pinpoint. Generally though we all have our own standards for good writing, good creation etc… Yet when it comes to criticism, we generally have better indicators. A formal criticism fails when it fails to comment on form. A historiography fails when it fails to explicate properly the entire history of a subject. Interpretation fails when it fails to provide a model of meaning as which to view the work. Only autobiographical criticism can shed all kinds of indicators and become fully conflated with aesthetics. Thus, while what is good art is generally subjective, we have better indicators for criticism because criticism concerns a type of knowledge.

From there we can get to the main question: Can Art be bad criticism? Of course. A work that contains aesthetics, but fails on its part to comment, or partakes in overt tenuousness, fails as criticism. In some cases we have great works of Art that fall into the realm of bad criticism, for example The Birth of Tragedy by Nietzsche, which makes really tenuous and highly likely untrue claims about Greek Art, whilst being extremely beautiful in its writing. On the other hand we also have Pale Fire, which is obviously bad criticism, though done purposefully, in that the narrator does not see the work as anything but a platform to start reminiscing about his convoluted past, and never seeks to provide any proper link between the two. We also have great criticism that tends to lack aesthetics (I won’t say completely though, because everything contains some amount of aesthetics). Any amount of academic journals and historiographies would count towards this. Borges essays on Dante count as Great Art and Great Criticism.

Generally when a person says ‘something isn’t art’, to attack the person on the realms of the abstract, namely to prove through metaphysical fluff that that thing actually is art, generally serves no purpose. By purpose I mean that it generally communicates nothing to the person who said the sentence. Art is a signifier that accommodates multiple intersections. Sometimes its used as an indicator for the level of aesthetics, other times its used as categorization. So when we see a Pollock painting, some are inclined to say ‘That isn’t Art!’ because it does not appeal to what they consider high aesthetics. Then the response that ‘Yes it is! Because everything is Art!’ serves no purpose other than semantical confusion. We’ve seen this with the Ebert vs Games thing. Whether this is the fault of the communicant or the receiver though, in that one has misunderstood the other, is highly subject to a multitude of interpretations.

In any case, I find it highly useless to make abstract attacks on that which is concrete. In the realm of the abstract, given the mismatch of information, and the multiple hazy signifiers of every sentence, any thesis or proposition can be proven to have credence, and anything with slight credence can be used to undermine the other, even though usually that isn’t the thesis that the other is getting at.

So when Sarah says ‘I don’t believe that criticism is art’, most likely she means that:

“I don’t believe that a person who seeks to write a work contingent on another and aims for communicating aesthetics is necessarily going to write a good piece of criticism, although it may be an aesthetically pleasing one, because generally a work that seeks aesthetics usually seeks beautification and rhetoric to undermine the aspects of its commentary that places the work in the realm of good criticism in the first place. Likewise I especially don’t think the above piece is either great criticism or great art because the claims it makes are tenuous and obviously it doesn’t seek to be aesthetically appealing. I think people who love to conflate the forms (of art and criticism that is) with abstract babble are people who generally don’t give a shit about writing good things, and by good I mean writing that serves to actualize things pertaining to the form of the work of art in question, of which the knowledge I can use in my own creation. Whilst I will not argue with your abstractions about whether it is good art or bad art, my statement, as a be-all-and-end-all assertion, seeks to imply that even if you attack me from the realm of abstract semantical philosophy, I find no interest in that because it provides me no knowledge or progress to my own goals, my craft, or my conception of aesthetics.”

(Hopefully I’m not misrepresenting your stand, Sarah. If I am, please clarify)

Whilst I understand the possibility of an assertion being an indicator of orthodoxy (for example with the assertion “Gays are not people”), I think its strange for you to attack Sarah on the realm of free speech. The example I gave is an example of denigrating a concrete (I mean there are concrete indicators for bisexuality) with an abstract. What Sarah is saying, in that ‘criticism is not art’, is undermining an abstract categorization with another. That doesn’t really ‘assault free speech’ per se, but rather communicates that “my usage of the word is different from yours, and my view of the aesthetics is different from yours, and because both are in the abstract private sense I can in no way communicate exactly why I find them different, but this is my usage, and this is your usage, so lets be clear on that”. Ceding to our own private language with regards to abstract categorizations, as long as it is in no way impinging on the concrete rights and matters (gay right to marriage for example) doesn’t seem to be an attack on free speech, which is all about ensuring that concretes cannot be attack by abstractions, by allowing for discourse so as to counter any hazy abstraction with speech from another person, and thereby attaining to a truth as to concrete matters. That is one of the primary and stupidest attacks all supposed ‘allies of free speech’ love to make.

Now let me deal with some contrary propositions that I can foresee, to the case.

1. It’s blatantly not true that a person who writes with aesthetics in mind can’t write great criticism, as you yourself gave the example of Borges’ essays on Dante.

Answer: Yes of course there are counterexamples, but when an assertion like that is made, especially with regards to art and creation, it serves as a principle standard for writing rather than an absolute rule. Look at it this way. Its easier to write with criticism in mind than with aesthetics. You can definitely posit an interpretation, or a formal analysis, or historiography with sufficient research and contemplation, but to write aesthetically whilst doing that is the whole struggle. Most people aren’t Borges, or even Nietzsche, but they still think that they can ooze poetics whilst providing startling commentary. In their effort to do so, they undermine the commentary at every instance, and their poetics are faulty and grating. Because its aesthetics, these faulty poets can tout their work as the ‘new avant-garde of the belle lettres’ or ‘the new amazing turn in continental philosophy’ and they will have the conception that there is no viable critique against them, because if you tell them that they write bad criticism, they will say “Oh I am merely proving the lack of consistencies in meaning” and if you denigrate their poetics they will say “my poetics is one of instability, and thus you cannot comprehend it”. On the other hand a person who seeks criticism can be trusted to accept criticism about his criticism, because he has lesser abstractions to throw in his path and shield himself from the failure on his part.

Of course it also seems tenuous for me to say that a person who places his faith in poetics will necessarily write bad criticism, or will use abstractions to shield himself from his case, but if you look at the plentiful examples of postmodern academia I think you’ll be able to see my point of view.

(By the way you gave the example of Zizek, who is quite entertaining, but is generally considered to be a great bullshitter in the philosophy department)

2. You said there are better indicators for criticism than aesthetics. Obviously that isn’t true because… Death of the Author! Postmodern incommunicability of meaning! Multiple word usage! Unverifiability! The realms of meaning are as subjective as the realms of aesthetics!

Answer: I like the answer that: although you can find multiple ways to say that the author and his intention may not match, you can’t say that no one created the work in question. Of course all this applies more to dead guys, of which we have no referent anymore, than living guys. It seems strange to root Brandon Graham firmly in the underground comix movement when he’s still currently alive and tweeting about just about everything in the world that interests him, of which underground comix is a subset, but so is a whole lot of other stuff.

Anyway I’m on the side of the analytic philosophers to say that propositions in the world are definitely in referent to some form of reality, and if both coincide then the proposition becomes true. There is always a difference between ambiguity of meaning and blatant extrapolation of speculations from a work in question.

3. Providing small scope commentary has its own uses, and serves to open up discussion in certain areas, for example as with the above, misogyny, taboo, and feminism. Even if the links are tenuous why should I be denigrated if my commentary opens avenues? Why must I write good criticism (that is, to fully represent the work that my writing is contingent on) if I’m sincere in my stance?

Answer: This is the part where I will maintain a firm moral foothold, and thus open myself to attack. A commentary that aims to be narrow, that never seeks to provide the counterpoint or clarify itself absolutely, and that never takes charge of a vast reality, is morally abhorrent (this phrase can be misunderstood, perhaps I should say “I find it to be pernicious and underlying the causes of strife, although not necessarily dangerous on its own”). The whole idea of free speech is to have communication cleanse communication, and discourse cleanse discourse, on the presumption that misinformation and misunderstanding is the primary source of orthodoxy, and thus the primary source of conflict. In our contemporary age we are realizing how vast and complicated things are, and now is the time that we have to develop a stronger critical capacity towards bullshit that seeks to posit huge statements on narrow realities. Although certainty is needed, it is always better to underlie every certain action with at least one or two doubts.

Contrary to free speech? Well contrary to people’s conceptions of it, but I’m not stating a rule or a law or anything, but rather I’m merely stating that if there is a room full of jabberers who always digress from the main issue, a heartful SHUT UP is perfectly justified provided that in the midst of that silence, a single voice is finally properly heard. There are bad SHUT UPs and there are good SHUT UPs, and high faultline assertive criticism (of the type that Sarah does) is a good type of Shut Up.

But is it not better for minorities to speak than to be silenced? For they have been silenced for so long! That’s true. But the main reason that so many contrarian bullshitters can mis-represent the cases of the various minorities, is that the cases of the minorities lacked the clarity to allow the bullshit to get through (by the way this is not a statement that minorities or feminists or whatever are doing things wrong, because I think that there are still waaay too many contrarian bullshitters for them to do anything other than to push through direct aggressive rhetorics in hope that people will at least hear the message, but I’m merely pointing out the state that has been reached. Maybe overload of voice is actually helping the case, even if all of their cases are highly flawed. I would need statistics or proper analyses for that though. I’m just stating my first intuitive response that sometimes its better to scale back speech and make things clear.)

This brings me to the next case

3.1. An assertion that does not state to be absolute, merely provides an approach, and thus is not conclusive, and thus is not aggressively making a case. It’s not harmful at all!

Answer: True enough, but remember that just because a person says “Well I think its possible to see banning gay marriages as justified if one takes the perception and stance of the Church” is also providing merely an approach, and is not at all asserting it.

That’s a hyperbole though, but the equivalent in this article (albeit not as extreme) is “Well I think its possible to see Brandon Graham’s work as a violation of good taste, rather than misogyny or insensitivity, if one see’s it in the frame of the underground comix movement”. Indeed I can say that the person who says this is not being definite and is merely providing an approach, but this approach he provides implies a few definites. It implies that the original Multiple Warheads was misogynistic and insensitive, and overall a violation of good taste. Those are the parts which I find Sarah is contending with, and that whole part was amply sidetracked by the whole ‘criticism and art’ question.

So we can see that the ‘approach’ was kind of like a nice pillow for the definite things that was being said about Brandon Graham’s work. Just as the ‘approach’ was a nice pillow (or in that earlier case, a nice lump of hard bedrock) to justify removal of gay rights. A nice bit of misdirection. We start thinking about the fanciful transgressions of Crumb and the rest and we forget the main crux of the case, mainly:

-Is it misogynistic if a pornographic work, which works on specific fetishes and titillations, depicts a disproportionate ‘idealized’ female?

-Is the reference to 9/11 insensitive or satirical (like the South Park episode after that)

-Is the Multiple Warheads in ‘bad taste’ or can it have all the above elements and still be considered aesthetically significant? The same way Shakespeare is aesthetically significant despite all his bawdy humor?

Whilst Sarah was probably the one who brought up the tenuousness of influence to the conversation in the first place, which led to the whole criticism can of worms opening, her usage of that term seemed more to be in the vein of “if you’re going to make a judgment of intention like ‘BG committed C due to misogyny’ it ain’t cool to say that its definitely because he was aping on the satirical misogyny of the underground comix, but rather BG has so many other possible influences and intentions, such as drawing the comic to get himself off, drawing the comic to get paid, drawing the comic in homage to Japanese Hentai movements, to New Wave sexually aware Science Fiction, to underground comix, to meld normal ‘sexy art’ with high fringe fetishism of Double Penetrating Wolf Dick in order to destabilize the conception of ‘ordinary sexual aesthetics’ etc…” all of which are perfectly plausible and may even all be correct.

Somehow this was read as “Sarah doesn’t like people talking about influences because she wants to be willfully ignorant of artistic homage, and she also hates criticism!”

Which I exactly what I meant by using an abstract attack on marble to protect the dignity of a stone. Side-drifting the conversation to attack Sarah’s aesthetics and opinions of criticism when all she was saying was “it ain’t cool to say shit about someone when you don’t know shit, and given that I’m his friend I probably know more about shit about that shit”. Well if you wanted this conversation to be fruitful in the realm of aesthetics, rather than that of gender politics, then I guess you’ve won.

But a case of criticism needs stronger links to be good criticism. This is the information era. It needs backing, or sources, or at least more reasonable links. Everyone knows the ol’ “objectification of women is caused when images of supposed ‘ideals’ are perpetuated by the patriachy to the extent where women get brainwashed into trying to live up to those ideals” form of argument. But the case that was brought up here is “pornography is exempt from that because a sexual ideal is, after all, a viable and unshakeable thing inside everyone, and while BG makes a claim of fetishistic preference, he isn’t stating a worldview whereby all women have to conform to that expectation”. I mean the other heroine of MW is a masculine heroine, and there are way too many gender ambiguous alien forms in all of his comics to demarcate what normative sexuality is, so making that claim is kind of being a complete ass to BG on that aspect. A case of misogyny can’t just be seen in the frame of a single pornographic work in a vast multitude. That is not good criticism.

And calling it ‘art’ is sidetracking from the case, and its bad usage, and there’s too many semantic errors that can lead to all sorts of other conclusions being made without commentating on the case. And if this comments section itself is not an example of what I mean by the possibility of digression in an information heavy society, then I don’t know what is.

I just spent 3 hours writing a 3000 word essay on a comments section. I’m a complete idiot.

That is a long comment!

I think there are a couple confusions. The first is when you say it’s not cool to say that BG was definitely part of the underground. Nobody said that. Phillip said, maybe this? Maybe that? So the repeated anger and hand waving about how dare he suggest this thing he didn’t suggest…I don’t get that. Chill out, you know? He started a conversation, he didnt throw down an absolute. I get that folks are friends with him, but come on. And the whole thing about, “how dare he imply…” Like, is Brandon Graham holy writ now? Possibly suggesting that maybe the comic has certain problems is grounds for censure, anger, and obloquy? If you disagree, disagree, and point out why you disagree. But the effort to accuse Phillip of the thoughtcrime of imputing thoughtcrimes seems excessive and self-contradictory, to me.

2nd, the effort to find formal reasons to separate crit from art seems weak. Largely because aesthetic genres aren’t formally defined. They’re ad hoc categories defined through social agreement or webs of resemblances. Maybe that makes Wittgenstein sad; that’s the way it goes for Wittgenstein. (I’m using Jason Mittell, Carl Freedman,and John Rieder’s approach to genre theory here, mostly.) Like, I’m not against the idea that reality is real, and that there are chairs and cats and possibly gender. But “art” is just not a thing you can separate from ad hoc social cues; it’s an agreed upon social category, not a brick. “science-fiction” is not a platonic form, and not even a well-defined formal truth, which is why people have arguments about the edges and even the center of what makes a genre. You don’t need to think reality is unreal to acknowledge that some categories are not solid, that understanding of truth can be ad hoc, and that some ways we organize the world are fuzzy. All meaning is not going to evaporate if you admit that there’s no good formal definition of comics, and never will be one. I don’t really understand the semi-panicked declaration that we must have clarity or we will sink into the abyss when you’re talking about art. This is art, you know? Ambiguity is generally considered a virtue; meaning is understood to be complex and confusing. But then you turn to genre definitions, and suddenly the ground will collapse under your feet if there’s complexity or confusion. The logic there escapes me.

Criticism has been part of art and artistic practice for 100s of years, at least, probably longer. It’s been seen as art way longer than comics have. Of course, the status is contested (as it is for comics) and these things are always amorphous. But to me when criticism is seen as parasitic, frightening, and by nature less valid and interesting then art, you get worse criticism — criticism that is unnecessarily deferential, which lacks ambition, which fails to account for and care about the history of the form. You get criticism which is supposed to abide by weird, arbirtrary rules…which is my problem with Sarah’s take. I don’t think she was just saying, this criticism is not something I’m interested in, or has problems for this reason. She was saying, this kind (or these kinds) of criticism are really invalid wholesale, and you should be embarrassed for writing in this vein because it’s solipsistic and bad. She’s trying to shut down certain kinds of conversations. Which, you know, isn’t the worst thing in the world to do or anything, but seems like an odd approach given her stated concerns about shutting down conversations (which I take to be the worry re porn comics.)

I mean, Sarah was read as saying you shouldnt’ talk about influences, because she made a pretty straightforward statement that you shouldn’t talk about influences, ever, and that people who did so were solipsistic. Your approach is more limited and less sweeping…but it’s not what Sarah said. (Maybe it’s what she meant; that’s always possible, of course.)

Also, this is contentious and confused:

“The whole idea of free speech is to have communication cleanse communication, and discourse cleanse discourse, on the presumption that misinformation and misunderstanding is the primary source of orthodoxy, and thus the primary source of conflict.”

No, it’s not. the idea of free speech, in my view, is that persecuting people and using state violence against people is really dangerous, and should be avoided if possible. People shouldn’t be attacked for speech if you can avoid it because abuse and violence should be avoided.

You want to know something that isn’t real? Progress. Another would be purity.

And by “shouldn’t be attacked” there, I mean shouldn’t be imprisoned and shot and so forth. Obviously you can criticize speech.

Is it not the case that by calling criticism “art” you actually loose something, rather than gain something? I mostly believe that everything is/can be art. But I do vacillate between art as an either/or proposition and a sliding grey-scale (my dentist says he sees what he does more as art than anything else). And inside the everything-is-art there are such activities as painting, poetry, music, that we call the arts. Mostly when someone says, “this is not art” isn’t it a way to say, “this is no good”? Art as a synonym for “I like this”.

And the art=aesthetics relation is a bit unstable too, after all the “conceptual” artistic work during the past 50-60 years (or 100, if you want some Duchamp). Some things can be called art without having any aesthetic considerations in the usual sense (like John Cage’s silent piece, for instance. Sure you can say it has aesthetic implications, and I’d agree, but not in a way you could compare to Schoenberg or Mozart).

Isn’t it the case that most people see criticism as another “thing” in itself? If we call it all just art, don’t we loose possible ways to deal with writing/art? Most people writing criticism want something else, don’t they? They specifically want you not to approach their writing as art. Which would bring us to the consideration of what you specifically should pay attention to with art – its formal aspects (what Sarah Horrocks was saying)

Criticism that is art to me would be, for instance, what Picasso did with Cezanne. Or Beckett with Joyce. Zappa with Varese. You take something (that is important to you) and make something new with it. And then what you have done is more art. And nobody will discuss it as criticism.

Just because it isn’t art doesn’t mean it can’t have an impact, can’t be felt and experienced level beyond some dry instrumental/informative level. Of course there is critical writing that exceeds mere commentary, that has more force, that affects you beyond what you normally expect or ask for – Virginia Woolf or Borges, as mentioned, or Walter Benjamin, or Theodor Adorno, or John Berger, or Samuel R Delany (to name 4 writers whose “criticism” affects me more forcefully than much “art”) etc. etc. So, this way we can simply say that writing (criticism) can have an impact without us having to call it art, right?

I think the problem is that when you say crit isn’t art, you start to insist that it be parasitic on art. That is, it’s purpose becomes to serve, or elucidate, or illuminate, this more important bright shiny thing. Whereas, I think the critical tradition has many different purposes and intentions and effects. Zizek and James Baldwin aren’t necessarily trying to get you to understand art better; they’re creating their own aesthetic object, which is meant to be true or beautiful or funny or surprising or insightful or strange.

Again, comics is really a lot more tenuously art than criticism is, historically. Crit has lots of high art cred and history; things like comics have generally been considered pulp crap not really worthy of consideration. And you still get people saying comics shouldn’t be considered alongside the other arts because its too pulpy/special/whatever.

I think John Cage and Duchamp aren’t outside aesthetics or art. Rather, they’re trying to push at the limits of what can be considered art,or showing the arbitrariness of art…or the aesthetics of the everyday. Those are entirely aesthetic projects, I would argue.

Well, I understand the Word “criticism” pretty much as “to serve, or elucidate, or illuminate”. Which I don’t see as something negative. Sure, a lot of criticism is parasitic. (Just as a most art is crap; comics, novels, movies, whatever – Sturgeons law, no?). But, it can also be symbiotic. Which is to say helpful, even if the “shiny thing” actually did come first and is more important. Criticism and art helping each other out. But the artworks survive longer than criticism, usually. Compare translations – the original work can survive just fine for hundreds of years, no translation does.

I still think it is worth having criticism as its own thing, With its own workings and history and so on. Closer maybe to philosophy or history, than to art. And some works of criticism do become classics, outlive the art.

Sure it’s been here longer than comics, but as its own thing.

Of course criticism can always be more than parasitic or symbiotic – if you use (a particular work of) art as part of the creative process, maybe taking off from a painting or poem to talk about life or whatever, which is perfectly normal, and quite common – and maybe then that isn’t criticism, but art. But that would be the thing, then it is not criticism, it is art; different things. Art can include “the critical”, and it’s just art. Again, lots of Conceptual visual art does this, and writers do this (Delany, for instance, or Huysmans, Mallarmé, Derrida, or Ronald Sukenick). I guess I just don’t see the point of calling it criticism. It’s just art.

I haven’t read much Zizek, I know he writes a lot about movies, but does he ever call what he’s doing criticism?

Zizek is doing philosophy and critical theory, I’d say. It’s like Derrida, who almost always has a critical project as a way to philosophy, or vice versa.

“Lasting long” doesn’t have anything to do with whether something’s art, does it? If you write a haiku and incinerate it as soon as you’re done, it’s still a haiku.

Lots of art is bad, but art has it’s own purpose, whether it’s bad or good; it’s not meant to be evaluated by how well it serves something else. I think that’s the case for criticism too. It can be bad or good, but it’s not parasitic. The Devil Finds Work doesn’t stand or fall on whether or not it makes you appreciate the Exorcist more. Maybe the other way around, since DFW is clearly (to my mind) the superior critical work.

Closer to home, Tucker Stone’s wonderfully funny reviews of mainstream comics were generally better than the comics he wrote about. That happens with some frequency; lots of bad art can be the subject of great criticism. I prefer to see the art that inspires criticism not as the thing to be illuminated, but as an inspiration—and of course art often inspires other art.

Oscar Wilde argued that criticism was greater art than art, since art is defined by artificiality, and criticism is more removed from reality (being art about art rather than art about the real.) He was being clever, of course—but he was supremely clever enough that his critical remarks are, I’d say, art.

Criticism and art are often so intertwined; dadaism or surrealism for example, or even impressionism; the criticism and the art there aren’t really separable. Comics doesn’t really have that tradition of critical movements, and instead has been defined as art in part against the critical movement of pop art, which is perhaps part of why there’s so much resistance to legitimating criticism in comics circles. I guess people may not realize it, but this argument is in a lot of way what’s defined the blog through its 8 years or however long its been now. The sense that comics criticism can be art, and the consequent demand that comics be seen as part of the history of art broadly defined, is central to what I’ve tried to do with the blog, and is why many people in comics view the blog with a lot of suspicion, anger, and mistrust.

I don’t know if there’s much more for me to say. I agree with almost everything.

“Lots of art is bad, but art has it’s own purpose, whether it’s bad or good; it’s not meant to be evaluated by how well it serves something else.” I agree. And I love the whole “art that inspires criticism not as the thing to be illuminated, but as an inspiration“ (I do that myself, mostly). And absolutely, surrealism, impressionism, much of modernism and postmodernism is playing with (and/or abusing) what came before – which is to say to have a critical relation to the past in a way that art did not have before.

Only I prefer to just call it art, not criticism-as-art, and keep the word criticism for something merely meant “to serve, or elucidate, or illuminate”. I think that is a worthwhile endeavor on its own. (Even if it does sometimes get parasitic.)

Lasting long has to do with quality, that’s why I mentioned it. Not the only marker for quality, but traditionally an important one. Maybe I’m wrong but it seems to me that what you propose is (in part) that art is about quality; that the word art has to do with quality. And commentary/criticism can be better than what is called the-work-of-art (movie, comic, etc.), or you can use “lesser” work as fodder (like Tucker Stone did – I miss those columns!), for something better, so it is also art.

Maybe I misunderstand, but it seems to me that that is part of this? To elevate criticism to art? (in the sense of quality) Or, I guess, to see that criticism has always also been art?

Yeah, for me criticism has always been art. Art can be good or bad; lord knows there’s a lot of bad criticism. I just want criticism to be seen as having its own integrity, not as being subservient to art—in part because I think both art and criticism are better, and more interesting, when criticism has more autonomy.

“The first is when you say it’s not cool to say that BG was definitely part of the underground…”

I wasn’t saying that he wasn’t cool to be underground. I was saying that he was accused of misogyny and low taste, and then the cause of this was ascribed to him following the vein of the Underground Comix movement. So Phillip had a picture of BG, and then neatly categorized him under the Underground, when I believe that neither the first nor the second is true. He’s different from the misogyny that comes from Robert Crumb (which is a confessional subversive form of misogyny). Crumb actually goes on about his objectification of women and all that with self-effacing humor. Brandon Graham makes fantastic worlds full of abnormal non-normative sex and blends together multiple styles from all over the place. Calling him Underground was never the problem in the first place. That was, I think, Sarah’s issue with influence. That is you’re ascribing a narrative onto an artist because of some mild correlations to other works, and furthermore an early work of his, not representative of his whole corpus. Which, I gave the analogy, of calling Joyce a Naturalist solely on the account that he wrote Dubliners.

“…social agreement or webs of resemblances…”

Well actually Wittgenstein agrees with that, that language is built from use rather than any inherent meaning. But I also think that definitions look different from different vantage points within society itself, for example the use of Negro to African Americans versus other races. You can tell that there’s no socially cohesive usage of that. Some use it to berate, others use it because they’re ignorant of its connotation and think its okay, others use it for idolization of the hip-hop subculture, whereas people within the race use it perfectly fine with one another, while some think that it shouldn’t be used altogether. Whilst there is a general social form to it, everyone has a specific private usage and its clashes about this private usage that leads to conflict, or misunderstanding.

Likewise the word ‘criticism’ can hold the whole spectrum from academic criticism, to using ‘art’ as criticism (Dadaists), to autobiographical ‘criticism’ etc… But its not at all useful to contend a person’s private definition with your own, because that only serves to underline epistemological differences between both parties. Rather you have to find out the intention of the others private usage and find a compromise with your own. Sarah expressed her private usage of the word, in the way that was useful to her, and found that the above piece by Philip didn’t fit her criteria for criticism, born from her own view that criticism about art that doesn’t discuss the aesthetics is kind of useless to her (http://whitelippedviper.tumblr.com/post/108010771622/threading-the-needle-on-contemporary-choices-in). But when she voiced this aggressively, other people took it like some kind of attack on the foundations of free speech and narrowness and all that.