So readers may have noticed that we’ve had quite a number of posts on Bart Beaty’s recent book Comics vs. Art. It’s a good book, but you may well wonder why we’ve (and especially I’ve) decided to spend quite so much time on it.

The answer is simple. Beaty stole all his ideas from me.

Consider.

— In his second chapter, “Defining a Comics Art World,” Beaty argues that comics should be defined in social terms — that is, in terms of a comics world — rather than in formalist terms. I made this argument on HU two years ago.

—Beaty has a lengthy discussion of the way in which art comics has presented Charles Schulz as a depressive genius and avatar of masculine frustration and self-pity in order to establish his high arts bona fides. I made this argument in the Comics Journal more than four years ago.

—Beaty identifies nostalgia as the central endemic feature of comics, and specifically argues that it permeates and defines not just superhero fanzines, but art comics as well. This has been one of the central critical argument of this site. Here’s just one example.

— Beaty spends a whole chapter focusing on Chris Ware’s performance of masculine self-pity, anchored in particular by a look at Chris Ware’s comics about high art. Again, I was making similar arguments, focused on some of the exact same pieces that Beaty discusses, a good while back.

I’m pretty sure I could find other instances too. (This blog has had a lot of discussion of the original art market for comics, for example, which Beaty talks about in some detail.) Reading Comics vs. Art was, therefore, kind of a bizarre experience. On the one hand, I kept turning pages and saying, “ha! I was right all along! See, a real academic says so!” On the other hand, I kept thinking…”Hey! I thought of that first! I even said it in the Comics Journal! Why don’t I get a shout out…or, you know, at least a citation?”

Of course, I’m sure the reason Beaty doesn’t cite me is that he didn’t get the ideas from me. I think most of these ideas (like, the importance of nostalgia in comics) are true — and since they’re true, of course all intelligent independent inquiry will naturally confirm them.

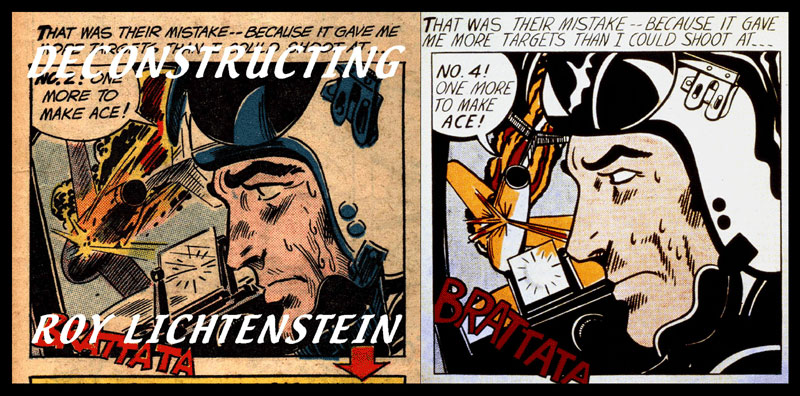

Still, it’s amusing that Beaty can be seen as in some ways enacting the same highbrow/lowbrow performance that is so central to his discussion. Just as Lichtenstein took the work of “lesser” artists and either elevated or stole it, depending on your perspective, so Beaty can be seen (with a little squinting) as taking the work of (ahem) lesser thinkers and elevating them, or swiping them outright. I am Irv Novick!

Again, I’m sure Beaty isn’t actually using my ideas. But it is kind of interesting that in his discussion of comics vs. art, and in his analysis of the critical conversation around these issues, he virtually never discusses the internet at all. The only time he really talks about the web, I think, is when he analyzes the effect ebay has had on the comics back issue market. But other than that, the ballooning online discussion of comics — the discussion that these days shapes the way that most people in the comics world think about comics on a day to day basis — is simply absent. Tom Spurgeon, for example, doesn’t show up in the index — though CR’s appreciation of a broad range of comics is hugely important in shaping the relationship between comics and art, or comics as art. Similarly, Dan Nadel pops up as an anthologist, but his seminal work with Tim Hodler at Comics Comics (leading to their editorship of tcj.com, isn’t mentioned.

Of course, you can’t talk about everything — but, as Beaty would be the first to acknowledge I think, what you choose not to talk about can be as important as what you decide to discuss. Beaty certainly knows about the blogosphere — he wrote regularly for CR for years. So the decision not to talk about the web and its place in comics criticism seems like it has to be a deliberate one. The discussion of comics vs. art is, for Beaty, one that is best approached through established institutions, and writers who have the imprimatur of established institutions, whether those be publishers or the academy — or fanzines, of course, which have longstanding status in comics. The web may shape practices (via ebay), but it doesn’t have anything in particular to say for itself. Or when it does have something to say, the voice Beaty cites is from Salon or the Electronic Book Review or the New York Times, rather than from the comics blogosphere.

The point here isn’t to indict Beaty (whose book I like a lot), but rather to point out the odd disconnect which remains between sholarly discussion of comics and internet discussion of comics. I call this disconnect “bizarre” because it seems to persist despite the fact that scholars (like Beaty) are all over the web. Charles Hatfield and Craig Fischer, for example, are longtime bloggers, and both have written for the Comics Journal (Craig has a column…as does Ken Parille.) There are a couple of specifically academic sites as well, such as the Comics Grid. And for that matter, my own blogging has given me the opportunity to write a book for an academic press. So obviously there is commerce between the two worlds. And yet, at the same time, there remains a cautious distance — such that Bart Beaty can write a whole book essentially about comics criticism without so much as nodding to the place where, at least in terms of sheer bytes, most of that criticism is occurring.

The reason to leave out the internet is fairly obvious; it’s for the most part not especially scholarly. This is a problem if you’re working on a scholarly project, because it’s hard to evaluate importance and worth when there are no credentials, because many people on the web are not speaking in a way that is of help or interest to scholars, and, last but not least, because it brings down the tone.

Tone is particularly interesting, because I think it’s one of the major differences between Beaty’s book and HU, and because that difference turns out to be surprisingly significant. Comics vs. Art is a confrontational book in many ways — but only to a point. Beaty slyly undermines the cult of Chris Ware, or the line between art comics and superhero fandom, or comics’ definitional project. But those jabs are always jabs rather than roundhouses, and they’re always from the scholarly stance of “this is an interesting phenomenon,” rather than from a more polemical vantage. Beaty’s arguments walk up to the line of saying, “people, you are acting like idiots, and you need to cut it out,” — but he never does cross that line. Which is why, when I paraphrase his arguments, adding a really-not-that-much-more-forthright polemical gloss, people tend to engage forcefully in comments — whereas, my sense is, Beaty’s own arguments themselves largely pass unnoticed.

In part this is just an aspect of the internets’ instant response mechanisms, and in part it’s probably because I’m not as credentialed as Beaty so people feel more comfortable (perhaps rightly!) in telling me that I don’t know what I’m talking about. In part, though, I think it’s because Beaty is deliberately working to be low-key. No doubt some will admire him for that, and there’s certainly pleasure to be found in his wicked gift of understatement. At the same time, though, his unwillingness to come out and take stand can make it difficult to figure out exactly why he’s bothering. What does Comics vs. Art hope to accomplish? Why is it worth pushing on the relationship between comics and art? If Beaty had his druthers, how might comics change?

I think Beaty’s answers to those questions would be similar to mine — that is, comics should be less neurotic and status-conscious, less inward-turned, more feminist, more adventurous, and more able to see itself as part of the arts, broadly defined, rather than as a defensive subculture which has to protect its own. Again, I think that’s what Beaty would say, but I don’t really know for sure. Maybe next time out he’ll tell us — whether or not he cites me while doing so.

Illustration of Bart Beaty by Martin Tom Dieck from Beaty’s staff page at The University of Calgary.