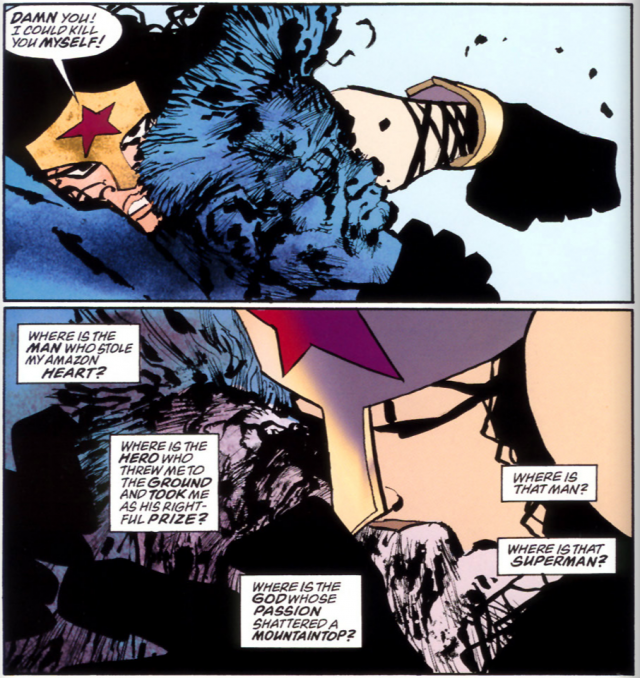

Cameron Kunzelman has a longish post up in which he tries to figure out what’s special about Wonder Woman as a character. Among other things, he talks about this sequence from the mess that was Frank Miller’s DK2.

As this suggests — and as the rest of Kunzelman’s discussion shows — Miller’s WW is largely defined by her relationship with Superman. Sometimes she mocks him, sometimes she fights him, and ultimately (as we see here) she is conquered by him. The whole point of having the strong woman woman there, for Miller, is to make the strong man stronger through his domination of her. Shortly after this scene, Superman grabs her and fucks her and she declares that he’s made her pregnant (“Goodness Mr. Kent, you could populate a planet!”) If you’re feeling flaccid, dominate the castrating bitch and soon you’ll be uncastrated. Wonder Woman’s the phallus which means (a) she can’t have the phallus, and (b) owning her is to own the phallus.

That’s not exactly where Marston is coming from, obviously. For Marston, strong women aren’t there to highlight the dominance of strong men. On the contrary, it sometimes seems like just the opposite is true — strong men only exist to be dominated by strong women.

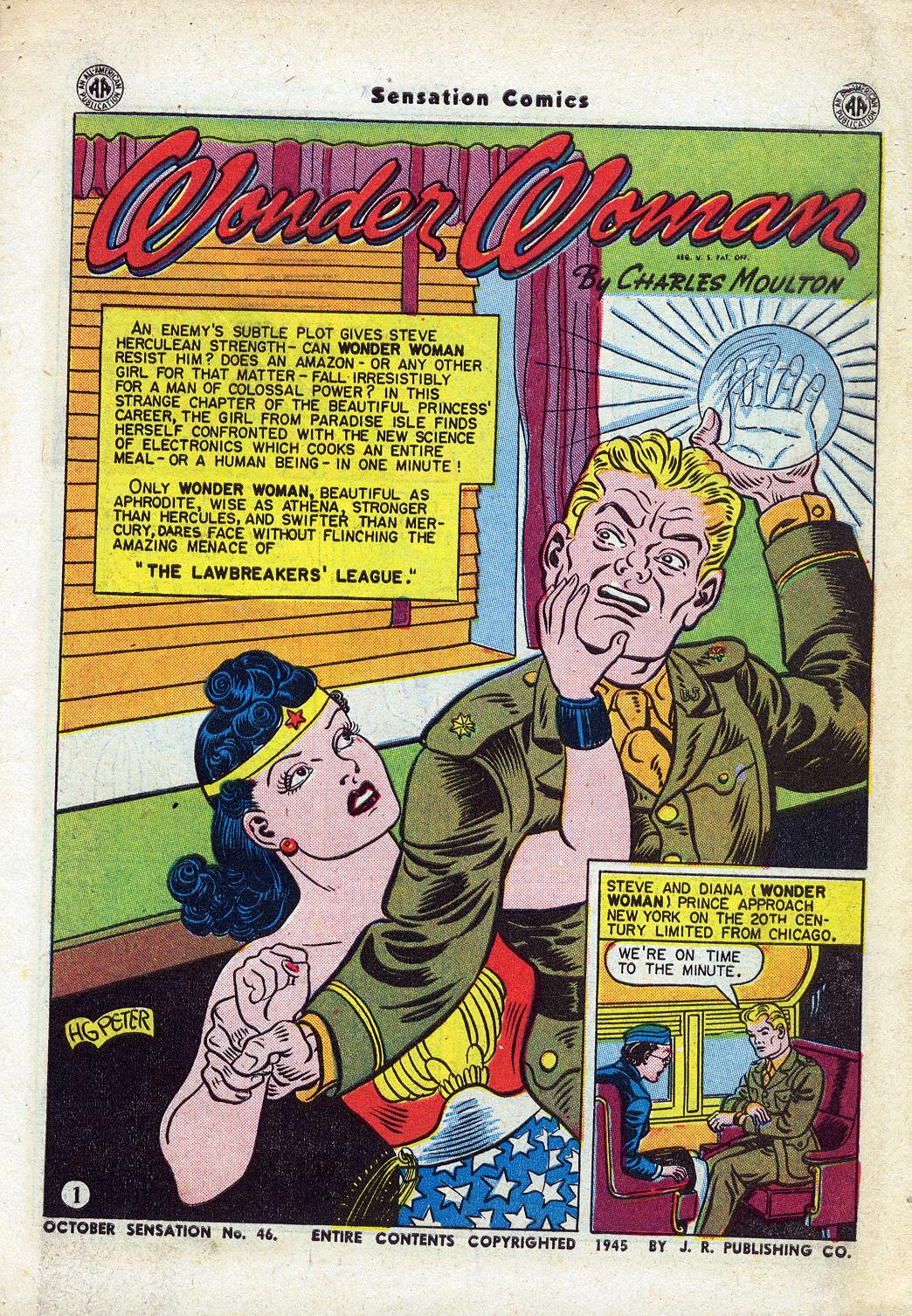

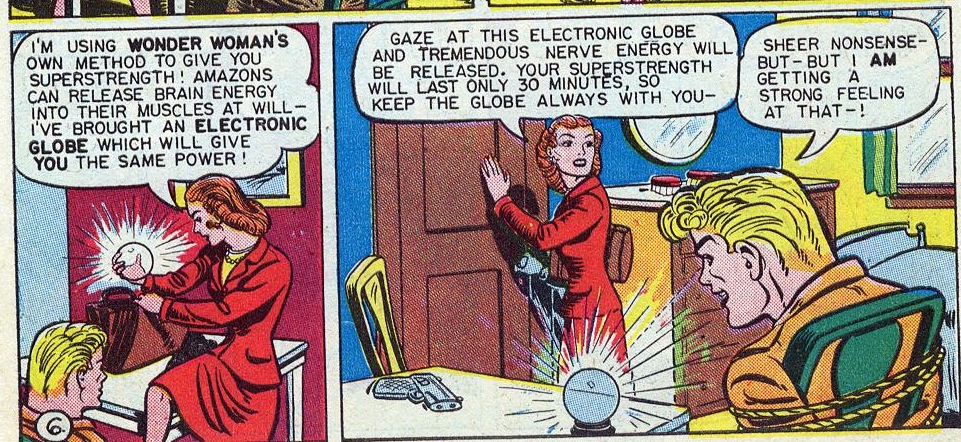

That’s from Sensation Comics #46. In this issue, like the text says, “An enemy’s subtle plot gives Steve Herculean strength!” A scheming female gangster figures that if Steve is stronger than Wonder Woman, he’ll get her to marry him, and then she’ll stay home and cook and clean rather than fighting bad guys. So she gives Steve an electrical (ahem) ball which makes him uberpowerful.

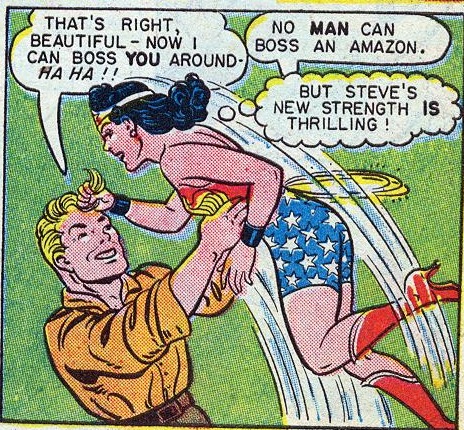

The plot works to some extent; as Wonder Woman says, Steve’s new strength is “thrilling.”

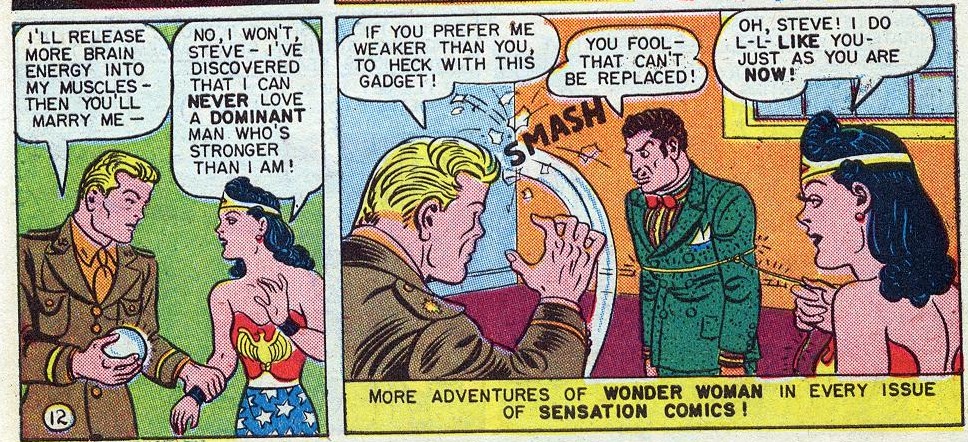

Ultimately, though, Wonder Woman decides that she doesn’t want a stronger man…

and so Steve does the right thing.

In some sense, this is, as I suggested, simply a reversal of Miller — in DK2, the strong woman submits; in Marston, the strong man does. Male/female is not a purely reversible binary, though; the two terms have long histories of meaning and inequity which aren’t simply substituted when you flip them. Men on top and women on top are different in more ways than just the positions of the bodies.

Specifically, Miller’s fantasy of men-on-top is about love as a seizing of power; love and force go together, so that when Superman fucks Wonder Woman, he literally sets off an earthquake. The power of the love is attested by its violence. Men on top express real love by seizing and destroying.

Marston disagreed. “Love is a giving and not a taking” he wrote in his psychological treatise. And so Steve expresses his love not by grabbing Wonder Woman and taking her as his prize, but rather by submitting. With women on top, love is giving up power, not seizing it; embracing weakness, not asserting strength. And where Miller’s version of love involves male dominance and excited female submission, Marston’s version of love-as-renunciation seems more reciprocal. Or, at least, Wonder Woman’s reaction to Steve’s weankness is not a swaggering assumption of mastery, but a blushing admission — “I do l-l-like you, just as you are — now.”

In this regard, I think this image is interesting:

That’s the sequence where Steve first gains his superstrength. The ball is given to him by a woman, obviously. In the first panel, she sits on the desk with her suggestive red dress, her legs spread — and Steve’s gaze seems directed at her crotch rather than at that glowing ball. At the same time, the women explains that the ball will do for Steve what Amazon training does for Wonder Woman. Thus, Steve’s strength is, both narratively and iconically, something taken from women — to be stronger is to be feminized. The point is further emphasized in the next panel, where Peter draws the usually chunky Steve with an almost bishonen grace — his blonde hair poofing out flirtatiously in front, his eyebrows curving eloquently, his lips unusually full.

In Miller, male strength emphatically enforces typical gender norms; Superman’s phallus turns Wonder Woman from battling Amazon to mother, and all is right with the world. In Marston, on the other hand, male strength feminizes…which doesn’t change the fact that when Steve submits out of love, he is also following a feminine ideal. Men on top reads gender straight; women on top, on the other hand, makes everything queer.

It’s probably needless to say that Miller’s version of the character seems to me in just about every way more conventional and less interesting than Marston’s. But more than that, I think Miller’s handling of Wonder Woman really suggests pretty strongly that Kunzelman is wrong when he says at the conclusion of his essay that “Wonder Woman is special.” After all, there’s nothing special about women-as-phallus; there’s nothing special about women as cog in male psychodrama. There’s nothing special (certainly not in Miller’s work) about fetishizing female strength in order to more fully fetishize the strong man who conquers it. Marston/Peter’s version of the character is touched by unique genius, of course. But that genius inheres in their writing and in their art, not in some random corporate property with a particular color scheme and appellation. If creators want Wonder Woman to be special, they need to make her special. Miller — and the vast majority of people who have worked on the character since Marston/Peter — haven’t bothered.