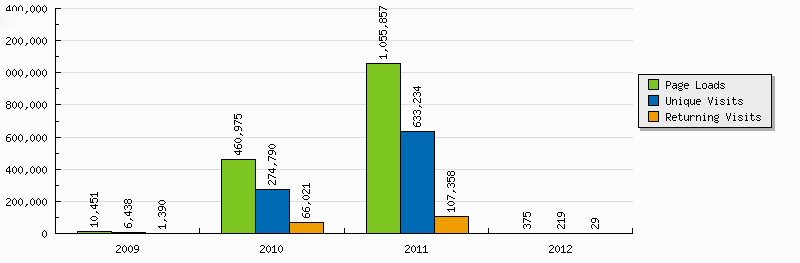

As our traffic bar graph above shows (click to enlarge), this has been an amazing year for HU. I thought I’d do a quick tour through some of the highlights.

Greatest Hits

There’s no doubt that the highlight of the year was Sean Michael Robinson and Joy DeLyria’s post in which they reimagined the Wire as a Victorian novel. Originally part of our Wire Roundtable, the post unexpectedly became a massive internet meme, picked up by everyone from Harper’s to the Baltimore Sun. It got more than 100,000 hits, and still, more than half a year later, is a fixture in our most popular posts list. A massive chunk of that leap in traffic up there is because of Sean and Joy’s post. I doubt we’ll ever reach those heights again, honestly…which is maybe for the best, as they busted our server.

Sean and Joy also landed a book contract on the strength of the post; the book should be out in a couple of months, I believe. Sean and Joy also had a post about Wuthering Heights, Unicorns, and joys of the publishing process, while Sean (by himself this time) had a nice piece about how being a meme affected his artistic process.

The other major traffic generator this year was Robert Stanley Martin’s International Best Comics Poll. More than 200 cartoonists, academics, critics, and other comics industry folk submitted lists to determine the 10 greatest comics of all time. Robert put an enormous amount of effort into organizing the poll, most visible maybe in the carefully annotated lists for every participant. It was a fantastic project, and HU was very lucky that Robert decided to run it here, and that so many other folks put in their time and energy to make it work.

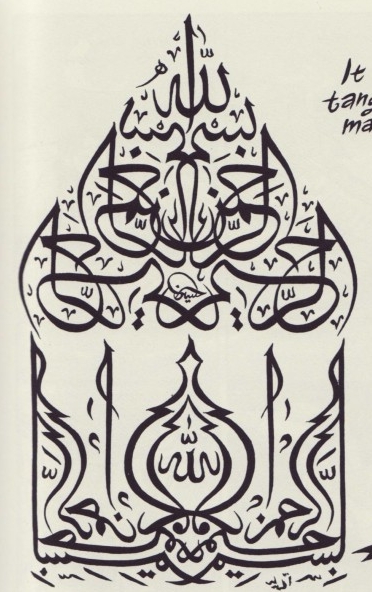

Another post which drew a lot of attention this year was Nadim Damluji’s discussion of Craig Thompson’s Habibi and Orientalism. The post sparked a long, occasional series of responses, including Nadim’s interview with Thompson.

Finally, this didn’t generate tons of traffic, but one of the things I’m most proud of this year was our Illustrated Wallace Stevens roundtable. A whole host of talented cartoonists and artists drew works inspired by Wallace Stevens poems. I couldn’t have been happier with how it turned out.

Kicked to the Curb

As some of you may remember, we started out this year as part of Tcj.com. In February, there was a shake up over there and we were fired with two weeks notice. Derik Badman did an amazing job setting up a new space for us, including engineering this site redesign you’re looking at. Thanks also to Edie Fake for creating our awesome oozy banner.

I talked about our year at tcj.com here, and commented on the pros and cons of their changed direction here. Finally, Mike Hunter eulogized the end of the TCJ message board.

More! More! More!

Here’s a sample of some other memorable moments from throughout the year.

Richard Cook on the Marvel Swimsuit issue.

Ng Suat Tong’s juried selection of theBest Online Comics Criticism.

Matt Seneca’s interview of CF.

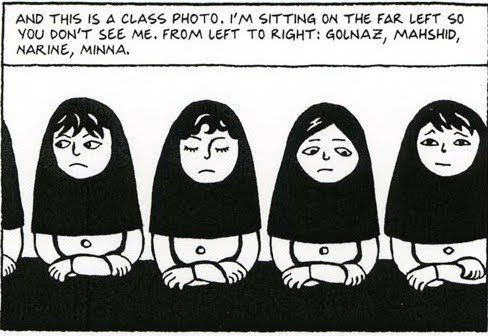

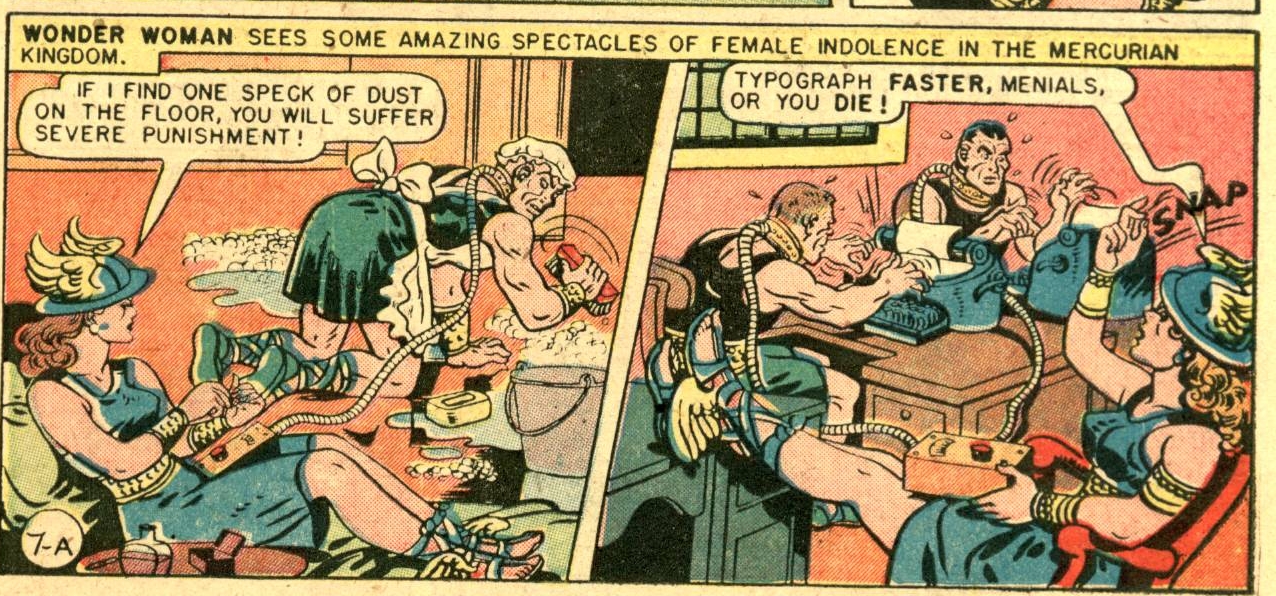

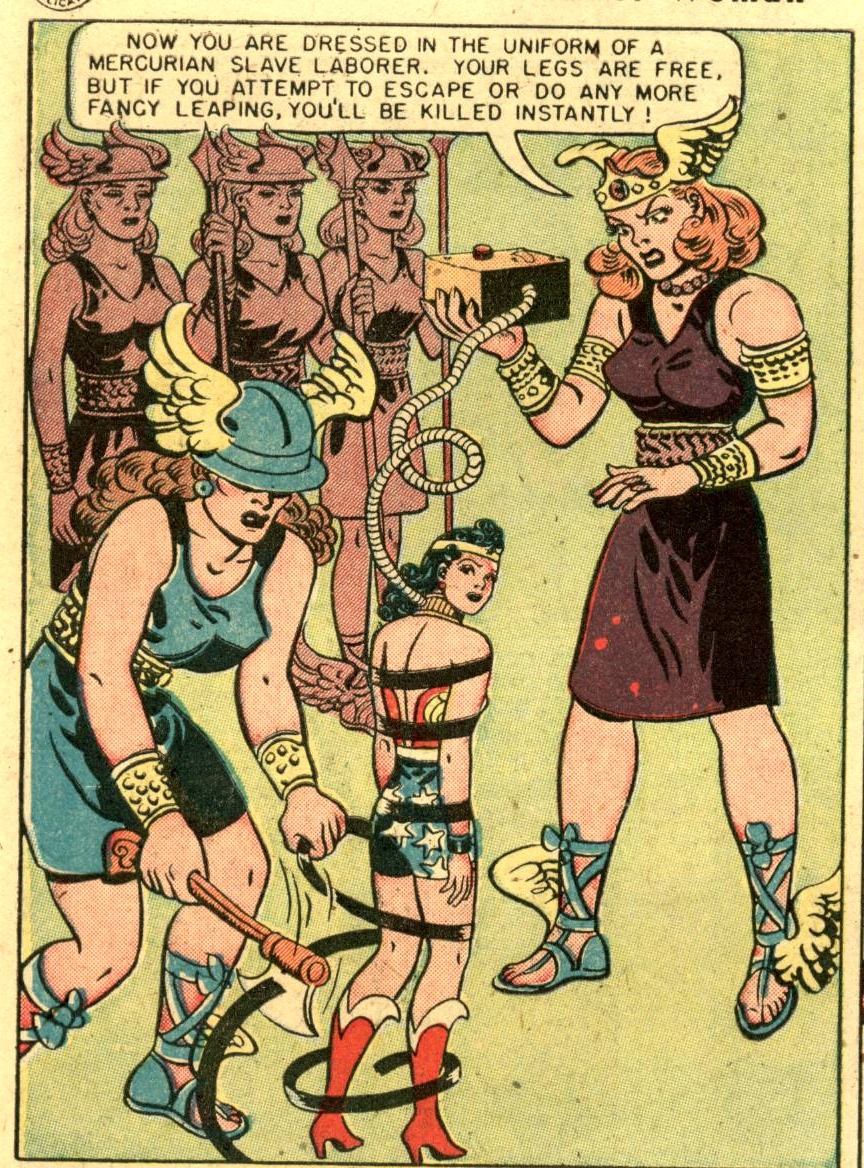

My interview of Sharon Marcus, focusing on queer theory, lesbian identity and (of course) Wonder Woman.

An unexpected visit by Diamanda Galas, Evil Bitch Fist and Party of One.

An extensive roundtable on Eddie Campbell’s Alec.

Tom Crippen presented a number of galleries of work by the cartoonist and illustrator Robert Binks.

Throughout the year we’ve had a bunch of posts on Twilight, of all things.

Tom Gill with a massive post on Tatsumi Yoshihiro and Tsuge Yoshiharu and fetuses in the sewer.

Anja Flower on the queer, interspecies allure of Edward Gorey.

Mahendra Singh on Jeffrey Catherine Jones.

My essay on Wonder Woman, superdicks, and Christ.

Yoshimichi Majima and Timothy Finney on questions about the original art sold by Manga Legends,

Kinukitty on Stevie Nicks.

A series of posts on R. Crumb and race, including Domingos Isabelinho’s post on the work ofAlan Dunn.

A roundtable on Chester Brown’s Paying For It.

Qiana Whited on Blues and Comics.

A blog crossover on Cable/Soldier X with Tucker Stone.

Ng Suat Tong Anders Nilson’s Big Questions.

Anne Ishii on Miyazaki and women in the animation industry.

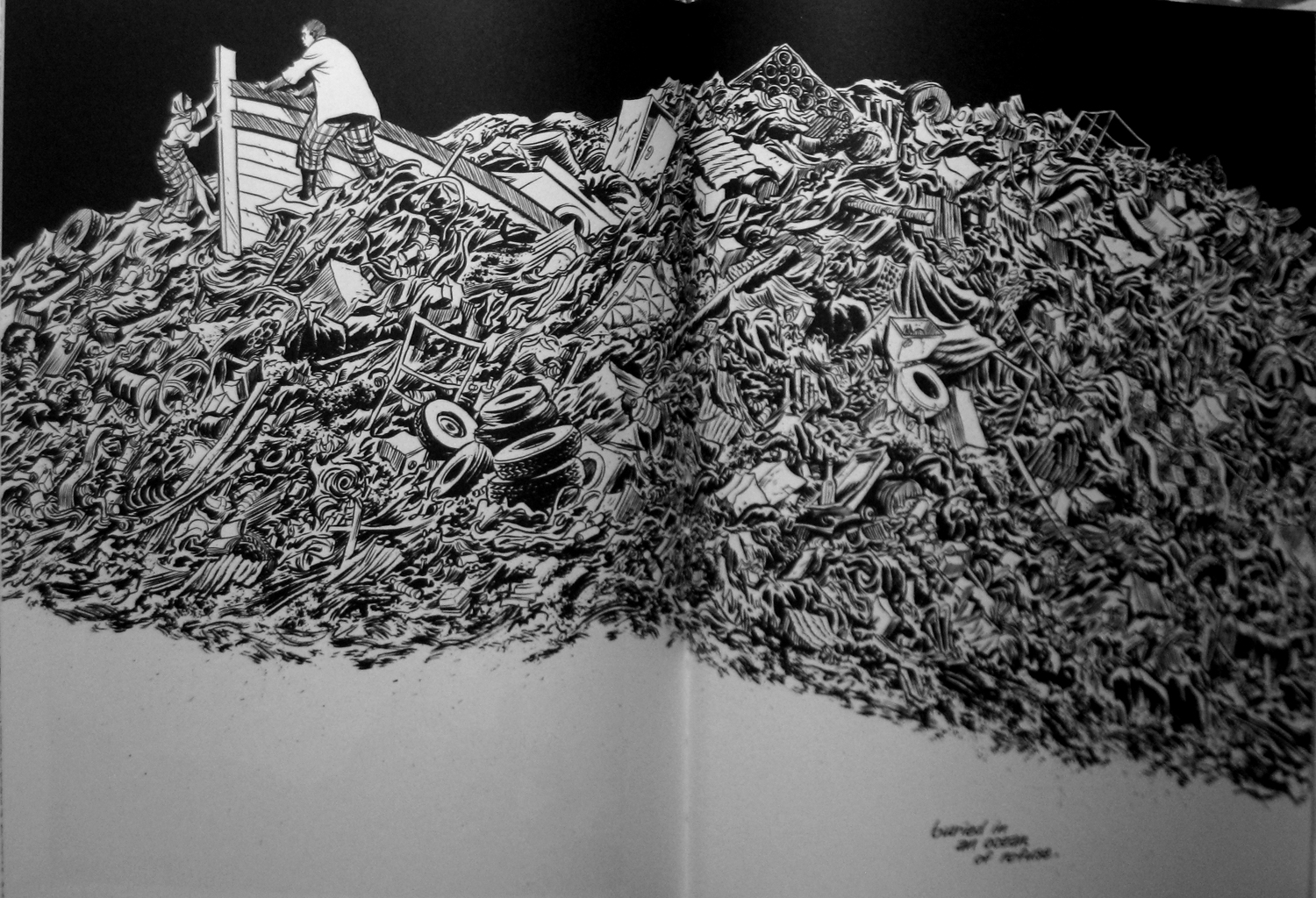

A roundtable on the Drifting Classroom.

A roundtable on Jaime Hernandez and his critics.

Erica Friedman on what’s the big deal about Sailor Moon.

A series of posts by James Romberger on Alex Toth.

A (still-ongoing!) roundtable organized by Caroline Small on Godard. This included the amazing shot-by-shot remake of Breathless by Warren Craghead.

And, of course, an occasional series of downloadable music mixes.

Utilitarian Future

We’re going to finish up the Godard roundtable, I know; there’s been agitation for a Jaime Hernandez roundtable; we may have some sort of celebration in September of our 5-year anniversary (presuming we make it that far!) — and beyond that, we’ll see. Thanks to all our writers, commenters, and readers for making 2011 a great year at HU. We’ll see you tomorrow to get started on 2012!