August 1980 – Page 96 Chain Mail

If you ever get the opportunity to look at a copy of the August 1980 issue of Heavy Metal, flip to the letters column on page 96. On the bottom left corner of the page, you will find a letter that I feel perfectly captures the mood of the average Heavy Metal reader during that year. It reads as follows:

Dear Ted,

The day is fast approaching when “reading Heavy Metal stoned is like being stoned… almost” (as one reader put it) is no longer true. Who can get into reading book reviews, movie reviews, and other such stuff when one is stoned? You sit there and stare at a paragraph for ten minutes before you realize you’re not even reading it, much less absorbing the content. I’d much rather sit staring at full-page artwork for ten minutes and really get into that.

I especially miss Druillet’s very worthwhile contributions[1]. So fire up another bowl and get HM back up to the top – where it once was.

T.H.C.

Decatur, Ind.

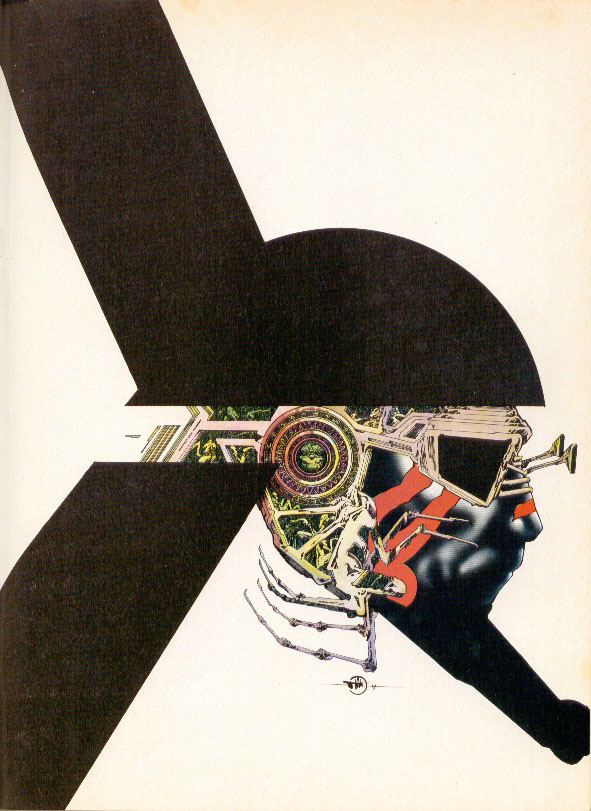

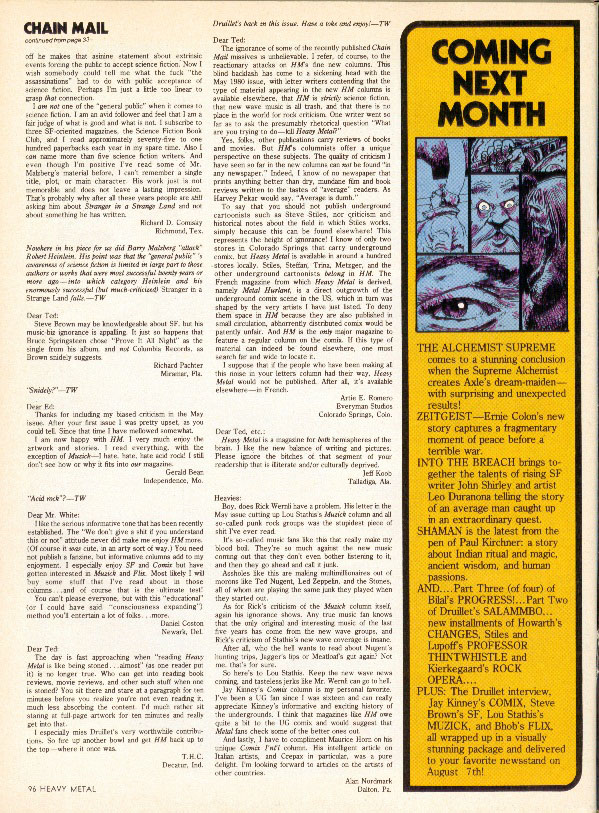

August 1980 – Page 53 Salammbo by Druillet

If online message boards, forums and/or Usenet had been widely available in the late 70s, the one(s) dedicated to discussing the content of Heavy Metal magazine would have exploded in controversy in 1980. This is obvious from the content of the letter columns during this year. The usual approach was to print a page of positive responses with an equal number of negative responses, followed up in later months by reactions to the responses. The printed responses were obviously just a drop in the mail bucket – I can only imagine what would have happened if it had played out in real time.

So what happened in 1980 to cause so much wailing and gnashing of teeth? Short answer: they got a new editor. Not quite two years after the inception of the magazine, the first editorial team of Sean Kelly and Valerie Marchant was replaced by Ted White, who had spent ten years editing Amazing Stories and Fantastic. At the time, it was felt that his success on those publications made him a good choice to take Heavy Metal in a new direction. It’s also interesting to note that the entirety of his comics-related work to that point was a Captain America novel he wrote in 1968.

The biggest (and most controversial) change that White brought to the pages of Heavy Metal were four columnists, each writing about a different topic – Lou Stathis, Jay Kinney, Bhob Stewart and Steve Brown. Original fiction pieces were dropped entirely and the volume of art pages was reduced to make room for column inches. To the editorial staff’s credit, they did play with the layout considerably, often presenting pages that were half text and half comic. Regardless, the huge blocks of text were easy to skip over and doubled the amount of time it took to read each issue.

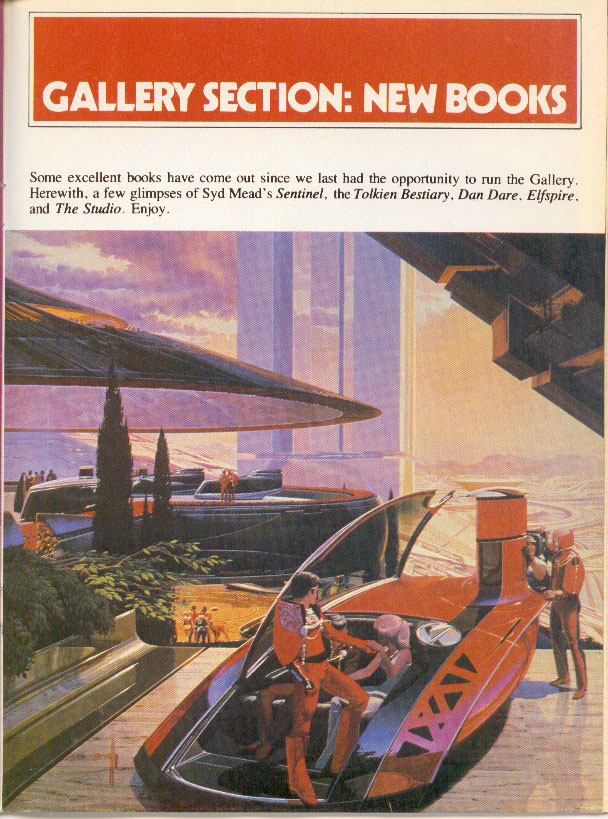

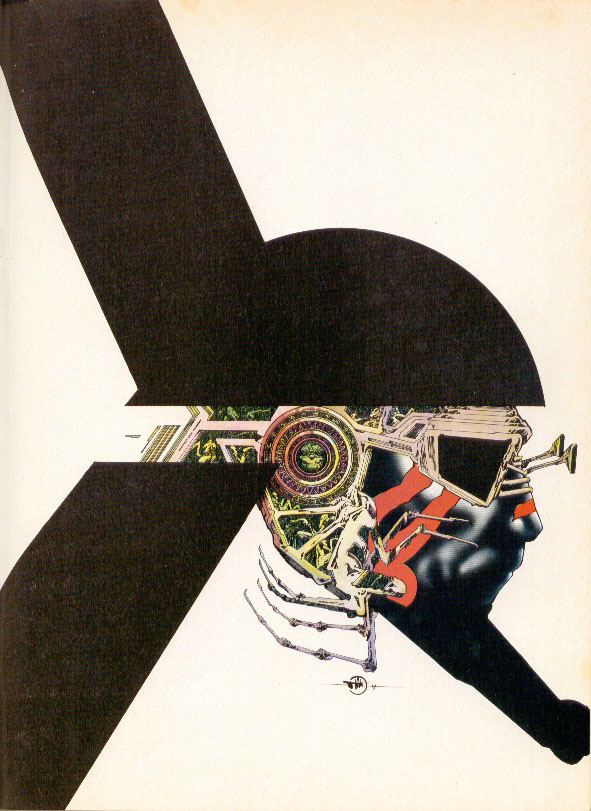

May 1980 – Page 57 Gallery Section: New Books

Of the regular columnists, the most controversial was Lou Stathis (who was an editor at Vertigo later in life). He insisted on referring to rok musick, an affectation that looks amusing now, but was probably seen as very progressive at the time. In his first column (January 1980), he starts by claiming that the only two acts that were any good during the 70s were the Sex Pistols and Roxy Music. This probably came as somewhat of a shock to the readers of Heavy Metal, who were mostly in the Led Zeppelin camp (a band that Stathis doesn’t even deign to mention in that first column)[2].

Stathis presented interviews of bands he enjoyed and did a review of a whole slew of debut singles at one point – up-and-comers like The Cure, X, and Gang of Four. Later columns included an homage to Brian Eno and a long examination of Ultravox, which ran next to Ted White’s review of an Ultravox performance written under the pen name of Dr. Progresso – a name that White still uses for his prog rock radio show. White wrote additional articles on occasion and the contrast in approaches is very striking. Stathis wrote from the hip, in his best Lester Bangs sneer while White’s articles were about sharing the love of an artform that he deeply respected.

In hindsight, it’s easy to make the case that Stathis’s attitude and contempt for what he considered to be the mainstream of music had the potential to severely alienate a portion of the existing Heavy Metal readership. Unfortunately, audiences tend to take criticism (real or implied) of the bands they like as criticism of themselves. After all, if you tell me that the music I listen to sucks, aren’t you also insulting my taste in music? As jazzed as he was about The Residents, Stathis was just as scornful of “the tuna fish that you get on your radio” and he constantly read like he was trying to pick a fight.

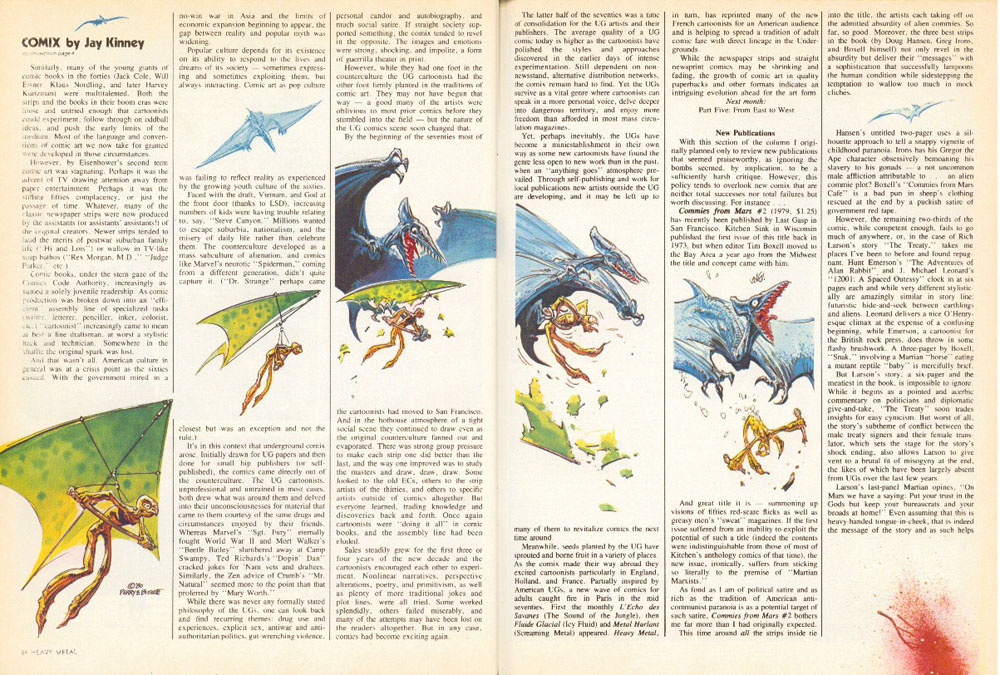

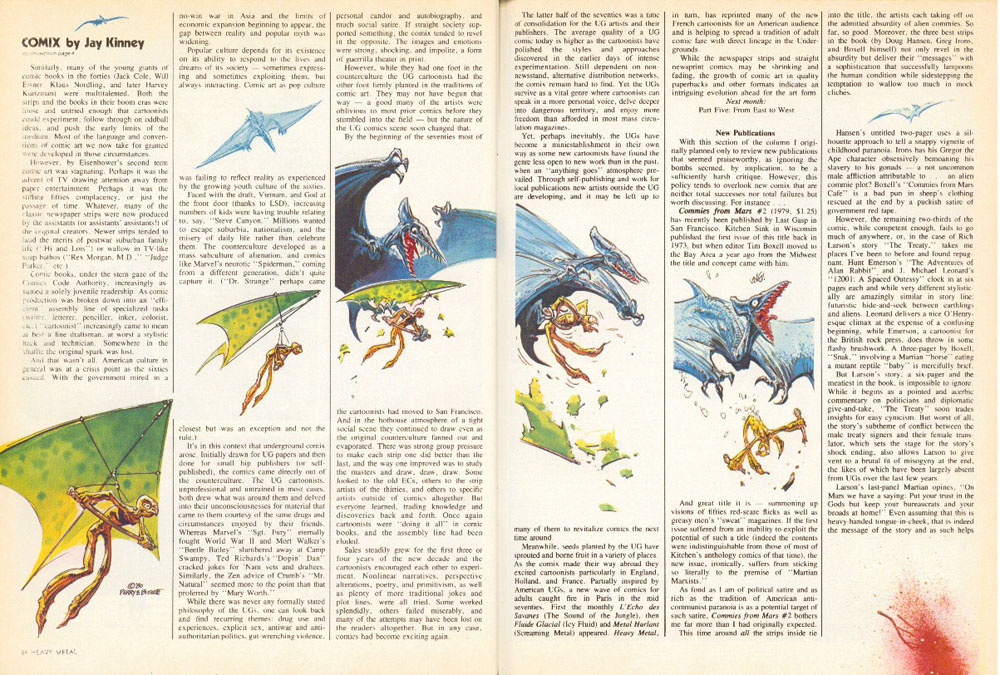

Jay Kinney’s running history of underground comix was nowhere near as controversial as Lou Stathis, but some readers still managed to find time to complain about it. Kinney started with one of the main influences of Crumb and company – EC – and sketched biographies and bibliographies for most of the big names in subsequent months. He only managed to get as far as 1971 with his history before his column was cancelled along with the rest of them in December 1980. Along the way, he provided a fairly good blow-by-blow account of the various underground cartoonists migrating around the country, looking for more reasonable markets (San Francisco and New York were favorite destinations). It’s a collection of columns that would form the good backbone of a definitive history of the period – as a companion to Dez Skinn’s book, maybe.

May 1980 – Pages 84&85 First Love by Bissette and Perry/Comix by Jay Kinney

Bhob Stewart’s Flix column was dedicated to film. His first three columns featured an extended interview with Stephen King, whose novel The Shining was being made by Stanley Kubrick at the time. Later columns focused on animation festivals, weird films that would now be put into the “psychotronic” bucket and a story about the time he met a background artist from Fantasia. He also did a long write-up of the upcoming Heavy Metal film, which was deep into production at the time.

Steve Brown’s SF column aimed at bringing news of contemporary science fiction and fantasy books to the readers of Heavy Metal. He reviewed David Brin, Samuel Delaney, Ursula K. Le Guin and a slew of other authors. Despite the occasional bully pulpit rant about how the science fiction genre deserved better, it was easily the least controversial of the columns because it was ostensibly aimed at a demographic that liked science fiction. Unfortunately, it was lumped in with the rest of the columns as a waste of space because those column inches could have been used for more art.

There were guest columns as well. Maurice Horn provided a quarterly international comics column. The April issue featured a write-up of Guido Crepax’s Valentina (Crepax’s thank you letter was published in July, alongside photos of a van that was painted with the Heavy Metal logo), August was dedicated to Herge’s Tintin and Tezuka was in November. April saw a hysterically ironic Sidebar column from Norman Spinrad that panned both the first Star Trek motion picture and Disney’s The Black Hole as being more about the special effects than the story – a criticism that has been leveled at Heavy Metal on more than one occasion.

During this period, Heavy Metal also ran interviews with certain key creators – Jeronaton, Enki Bilal, Moebius, Philippe Druillet and Guido Crepax. In most cases, these were the first English-language interviews with these creators and exposed the readers of Heavy Metal to more than just their art. Jeronaton was all over the place, but the Druillet and Bilal interviews are excellent insights into the artistic and creative influences that shaped them and their productions.

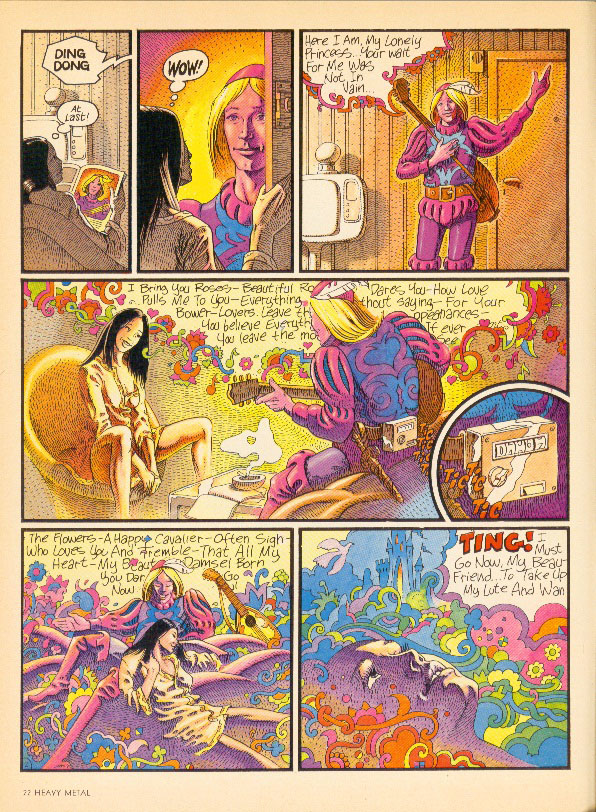

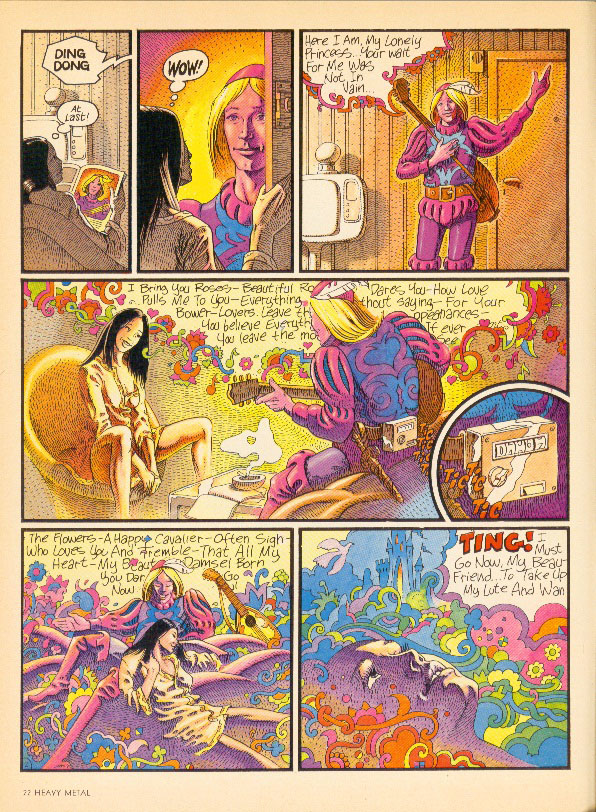

Scattered among the columns were some top-notch comics work. Berni Wrightson, Spain Rodriguez, Joost Swarte, Guido Crepax, Howard Cruse and Matt Howarth showed up in Heavy Metal for the first time during this period and a lot more of Rick Veitch and Steve Bissette’s work was also evident. Several of Caza’s pieces from Pilote appeared, as did a lot of older Moebius material – including a great strip from when he was going by Gir. Ted White even did a few strips with Ernie Colon. Chaykin didn’t show up, but early Corben did – from the period before he discovered the airbrush.

May 1980 – Page 24 House Ad

Despite the fact that he oversaw one of the best issues of Heavy Metal ever produced – the Rock Issue, October 1980 – Ted White did not make it to the end of the year. The last issue he edited was November 1980, but the columns made their last appearance in the December issue, which makes me think that his departure was fairly abrupt. Controversy may be good for raising awareness of a publication, but when the self-identified long-term readers[3] start complaining about the format of a magazine that they have grown to love, it’s time to make hard decisions.

After acknowledging that “[s]ome of the ideas worked, others didn’t,” the editorial in the December 1980 issue laid out the new status quo and claimed that White “is now relinquishing his duties as editor to devote his time to two novels and his new record company.” He was scheduled to do a tribute to Will Eisner in an upcoming issue and wrote a few follow-up comics, so the split wasn’t entirely acrimonious.

Some of the changes that came out of 1980 were subtle– the overt drug references didn’t go away, but the rolling paper ads were replaced by ads for stereo equipment and science fiction book clubs. Guest editorials and commentary continued in later issues, as did interviews. White introduced a portfolio section, which showed off samples of art books by Syd Mead and HR Giger. This was later resurrected as a general presentation feature called Dossier that ran for years.

July 1980 – Page 22 Romance by Caza

If you were to cleave the history of Heavy Metal into distinct periods, the Year of Ted White makes a neat dividing line between the fast and loose production values of the early years and the more professional publication that was eventually given to Julie Simmons-Lynch. It’s a shame that it was only a year, though.

[1] Druillet had an excellent piece published in the same issue.

[2] A letter in the May letter column starts by asking the rhetorical question “What is the most useless person in the world?” and answering it with “A rock critic” then goes on to argue that New Wave music is terrible by citing the complete lack of talent exhibited by Devo, Elvis Costello and the Talking Heads.

[3] Of a magazine that’s just over three years old