(A call for nominations and submissions.)

This is part of an ongoing quarterly process to find the best online comics criticism of 2012. Five comics critics have kindly agreed to adjudicate and create a final list based on the long list of nominations. Nominations from previous quarters can be found here and here.

We’ve just ended a lengthy Hate Anniversary at HU and judging from the results, it would appear that “hate” is both entertaining and popular. On the other hand, it does seem that “hate” isn’t as easy it appears. My feeling is that while the criticism generated in the last few weeks has been useful and informative, less of lasting worth (to comics) has emerged than in previous HU roundtables. In fact, I would not hesitate to say that one of the worst pieces of comics criticism I have read this year emerged during this roundtable.

The usual reasons—as listed by Noah in his introduction to “hate”—apply. I am also puzzled as to the repeated justifications for “hate” in those articles. Rather, writers should be apologizing to readers and consumers (like myself) for loving so much dreck. There’s always the small possibility that the world of comics criticism is, for the most parts, a happy-clappy world of positive energy with practitioners ill-suited to the arts of ridicule and general nastiness. The preponderance of words of affirmation in this year’s nomination list is evidence of the same. There are far worse things then this to be accused of.

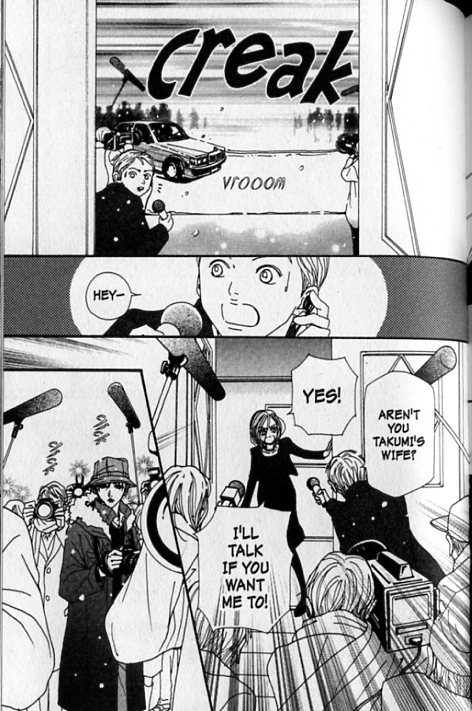

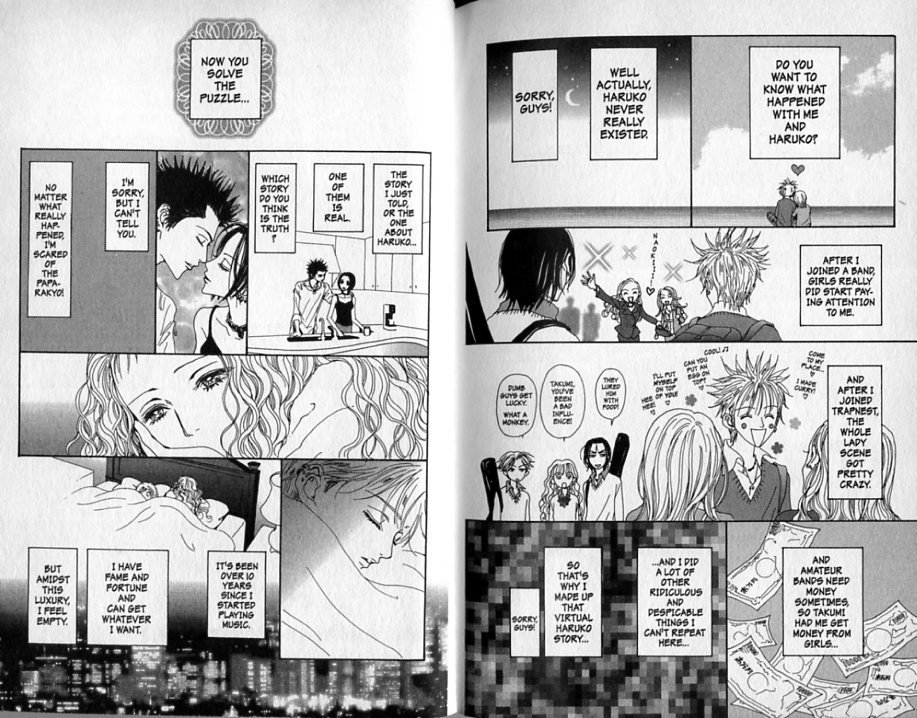

[Geoff Johns and Doug Mahnke’s Allegory of Criticism.]

Reiteration: Readers should feel free to submit their nominations in the comments section of this article. Alternatively I can be reached at suattong at gmail dot com. Web editors should feel free to submit work from their own sites. I will screen these recommendations and select those which I feel are the best fit for the list. There will be no automatic inclusions based on these public submissions. Only articles published online for the first time between January 2012 and December 2012 will be considered.

There were a number of good articles on HU this last quarter but I won’t be nominating most of them due to a conflict of interest. Readers (but not contributors) of HU should submit their own nominations for this quarterly process.

***

Jordi Canyissa – “Pictureless Comics: the Feinte Trinité Challenge”

Jared Gardner on Joe Sacco – “Comics Journalism, Comics Activism”. This one was recommended by Noah. I will add here that I’m definitely not sold on the idea (suggested in the text) that Sacco is under appreciated or polarizing. If anything, there’s almost universal support for his political positions and comics within the comics critical sphere. He certainly hasn’t been kicked around like Norman Finkelstein for example. This might actually reflect well on comics critics for once but I’m more inclined to put this down to a lack of diversity in opinion.

Laurence Grove – “A note on the woman who gave birth to rabbits one hundreds years before Töpffer.” (According to the author, the article has appeared as “A Note on the Emblematic Woman who Gave Birth to Rabbits”, ed. Alison Adams and Philip Ford, in ‘Le Livre demeure’: Studies in Book History in Honour of Alison Saunders (Geneva: Droz, 2011), pp. 147-156.)

Dustin Harbin on Steven Weissman’s Barack Hussein Obama.

Jeet Heer on Building Stories (“When is a book like a building? When Chris Ware is the author.”)

Christopher J. Hayton and David L. Albright – “The Military Vanguard for Desegregation” (from ImageTexT)

Nicolas Labarre – Irony in The Dark Knight Returns.

A. David Lewis (writer) and Miriam Libicki (artist) on Harvey Pekar’s Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me. This is a useful Jewish perspective on a comic about Jewish matters. The problem as with most drawn reviews of comics is that it really doesn’t use the tools of the medium in any useful sense. Much of it reads as if it was adapted from a prose form review as opposed to a comics script. This review didn’t need to be a comic.

Heather Love on Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother (“The Mom Problem”).

Mindless Ones on League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Parts 1 and 2

Adrielle Mitchell on the relationship between Comics Studies and Comics. (“Mutualistic, Commensal or Parasitic?”)

Alyssa Rosenberg on Doonesbury.

Marc Sobel on Alan Moore’s “The Hasty Smear of My Smile”. Part of a guest written series on Alan Moore’s short form works at Comics Forum.

Steven Surdiacourt – Graphic Poetry: An (im)possible form?

Matthias Wivel – “New Yorker Cartoons – A Legacy of Mediocrity” (as published on HU).

Frank M. Young on John Stanley’s Little Lulu Fairy Tale Meta-Stories. I’m including this article here despite the rather ridiculous comment near the start that Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant and the Tarzan newspaper strip aren’t comics. It’s an argument from the Land that Time Forgot which Young explains in detail in the following short summary:

“But part of the distinct recipe of comics is the speech or thought balloon. It is a narrative device unique to the form. The creation of this tool, in the 19th century, gave comics the one thing that set them apart from prose, paintings, plays, movies, video games, TV shows and any other visual-verbal container for a flowing narrative.”

The real question here is whether an outdated and eccentric idea about comics should detract from the piece.

From The Comics Journal

Rob Clough on Dan Zettwoch’s Birdseye Bristoe.

Craig Fischer – “Devils and Machines: On Jonah Hex and All Star Western”

Richard Gehr on The Carter Family.

Joshua Glenn – The Pathological Culture of Dal Tokyo.

Ryan Holmberg – “Tezuka Osamu and American Comics”

Bob Levin – “To Hell and Back”

Dan Nadel on David Mazzucchelli’s Daredevil: Born Again Artist’s Edition.

Sean Rogers – “Flex Mentallo and the Morrison Problem”

Carter Scholz on Dal Tokyo.