More than 15 years after its initial debut in Japan, and just about 10 years since its debut in America, the Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon manga is making a comeback, with a brand new edition in English from Kodansha, Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon.

Of course there are many fans that are thrilled by this – I count myself among them. For those of us who love this series, no explanation, no reasons, no critical analysis need be applied to the series. We love it, full stop.

However, the refrain I’m hearing over and over from those people who did not catch the wave the first time around, is “I don’t “get” it. What’s the big deal?”

First of all, let me disabuse you of the notion that there is a Big DealTM about Sailor Moon. There isn’t. If you don’t like it, don’t “get” it, can’t understand what we’re seeing, you’re not missing anything critical. Let’s be honest here – if you think Usagi is annoying, and don’t like the premise, the clothes, the romance…there’s nothing I can say to change your opinion. You don’t like Sailor Moon. Own it. I don’t like Dragonball Z and nothing any one of the zillions of fans is ever going to say will change my opinion.

So…what is the big deal about Sailor Moon? Let me tell you my story.

I used to collect American comics. I still have long boxes full of Avengers, Defenders and Invaders. But honestly, by the late 80s my interest was waning. Janet hadn’t killed her asshole husband Hank yet and the Valkyrie still wasn’t lesbian, even though she obviously was. There were fewer and fewer good female characters. When Storm joined the Avengers, and the Legion of Superheroes couldn’t tell that Quisling was the traitor among them, I knew I was done. Although I stopped collecting, I didn’t get all anti-comics. I just left comics and stopped filling the longboxes. I kind of missed the stories, but not enough to go back. Indie comics were too full of themselves (and had no women either) so I just…stopped.

In the late 1990s, anime and manga were starting to become popular here in the US. Cartoon Network used power anime series Dragonball Z and Sailor Moon to spearhead an afternoon anime block. It broke all records for animation in America.

I knew of it, of course. By then I was already making tentative steps into derivative fan work, with some fanfic of Xena: Warrior Princess and, for the first time in many years, found my interest in comics returning…only this time, it was all about manga. Friends came to the house with anime; we watched popular series like Ranma 1/2 and Tenchi Muyo and it was all laughs and fun and games.

So when my wife was home unemployed, and she started watching this series on TV called Sailor Moon, I wasn’t all that surprised that we liked it. I’ve told this story many times, that the first episode I watched was titled in English “Cruise Blues” and when Amy asked Ray if she noticed that they were the only ones on the ship without boyfriends and Ray replied that they didn’t need boys to have fun, I turned to my wife and said, “We are watching two different cartoons. You are watching the pre-pubescent little girl cartoon and I am watching the one with tremendous lesbian subtext.” And so, we were both hooked.

I started to research this Sailor Moon and instantly encountered the fact that two of the Sailor Senshi were a lesbian couple (and this outside of the not subtle lesbian subtext between Usagi and Rei, Minako and Makoto, later Ami and Makoto, and in the manga Minako and Usagi and Rei and Minako. It was actually kind of hard to avoid it, unless you worked hard at it.) And then there was the obvious, incestuous triangle of Usagi, Mamoru and Chibi-Usa. And that was only in the first two series!

Once I learned about the third season, the appearance of the “Outer Senshi” and the fact that they had what was as close to an out lesbian couple as I’d ever see in anime (this was back in the late 90s, remember,) I dug around until I found fansubs of the series. Fansubs weren’t easy back then. You mailed a blank VHS plus postage to some guy somewhere and he sent you back a VHS with a nth generation copy with subtitles manually entered and timed. If you were lucky, the guy was making copies from an LCD.

That’s how I discovered Sailor Moon Super or Sailor Moon S, as most people call it. And how I discovered Sailors Uranus and Neptune, who are indeed a fabulous lesbian couple.

As my wife and I watched Sailor Moon S in Japanese, I realized I could parse some of the linguistic patterns and since I really, really wanted to read the manga for this series (it was still years before Tokyopop would consider putting it out) I started to learn Japanese…just to be able to read Sailor Moon.

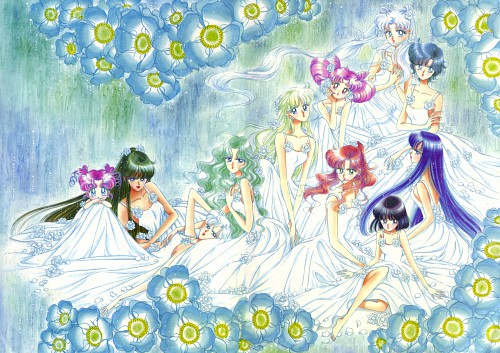

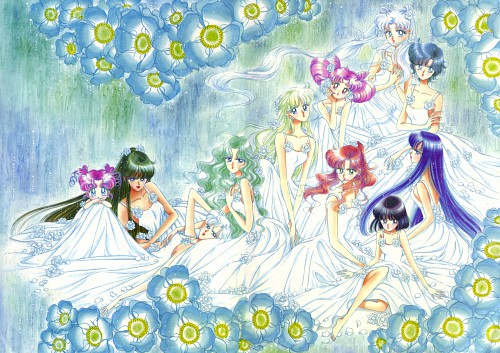

The manga was pretty sketchily drawn. Takeuchi’s feet and hands are not worthy of praise. But her characters are beautiful. Yes, they all have the same face…there’s darn few manga artists that don’t do a find and replace face. That’s exactly why hair styles and colors are so strange in shoujo and shounen manga – because otherwise all the characters have the same features. And yet, those lines are lovely, feminine and appealing. Takeuchi wasn’t afraid to dress her characters up, or play a little with their personalities.

The plot is…childish. A slightly-below average middle schooler is the leader of a group of “Guardians” from an ancient Moon Kingdom? Well, gosh that makes tons of sense, doesn’t it? I have two words for you – Dragonball Z. The plot doesn’t have to be sensible, any more than Cinderella’s fairy godmother giving her a glass slipper does. Sailor Moon is childish because it’s written for children. For girl children who want to be Princesses who fight for love and justice and who get the guy, but get to rule the Queendom, rather than adorn the King’s arm. Not for nothing is Queen Serenity accompanied by Prince Endymion. But all the characters were, at heart, girls that any girl might identify with. Girls who are a little – or a lot – different. Each Senshi reflects an archetype, a zodiac. Each Senshi reflects us.

So what is the big deal?

It was a series for girls, when little to no series took girls seriously. Like Xena, Usagi fought for good. Like Xena, Usagi gathered around her allies and enemies. Like Xena, Usagi’s allies become more than just friends. Unlike Xena, Usagi was just a regular girl. Perhaps it was the zeitgeist but for me, having Xena and Gabriel on TV paved the way for me to love cool, attractive Junior Racer Haruka and genius violinist Michiru. The anime fed into the manga, which fed back into the anime. Character qualities and experiences spilling from one into the other and back created a body of canon, fed by the deep well of fanon in the form of fan art and fanfic (many dozens of which I wrote and still ocassionally write) that created the spring with which our fandom was irrigated.

I don’t know if anyone coming to Sailor Moon now can feel that, but I do know it’s been on the New York Times Best Seller list since Volume 1 was released. I’m not surprised at all. Usagi is still annoying yet lovable, Ami is still admirable and sweet. Makoto is strong, yet feminine. Minako, when she arrives will be goofy, but a staunch leader. Setsuna will be mature and mysterious, Chibi-Usa will be 10x annoying, but sympathetic, Haruka and Michiru will be talented, cool, and deeply, obviously in love. And last, but almost never least, Hotaru will be pitiable and amazing.

What’s the big deal about Sailor Moon?

You tell me.