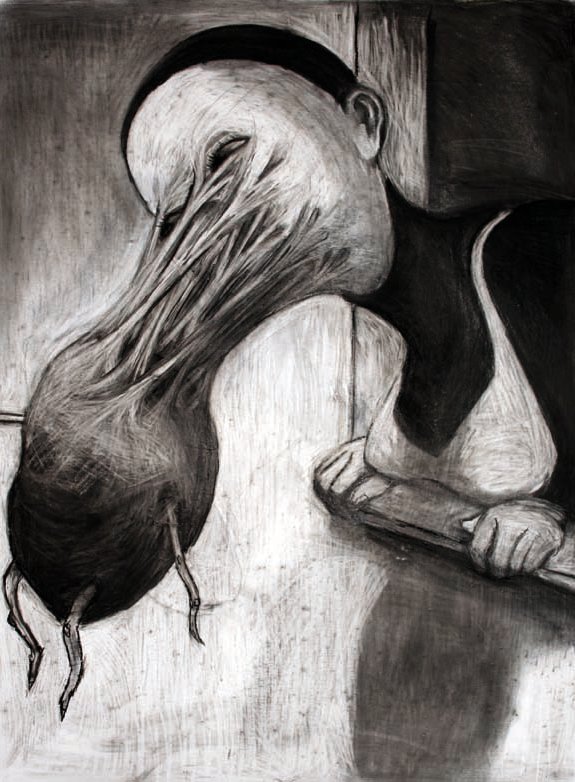

I was a teenager the first time I saw a drawing by Robert Crumb, and I had an immediate, visceral reaction, a feeling of nausea, a slightly floating, psychic displacement from my physical self. I don’t remember now what the specific image was, nor does it really matter at this point—it wasn’t the content that repulsed me, but the neurotic, shaky, compulsive lines, invading every form, erratic, descriptive of the hand that made them as much as the subjects themselves.

My disgust deepened after my first exposure to his comics—they seemed so tightly drawn, so cluttered and cramped that I felt anxious, trapped in neurosis. And when I did, finally, make it past the surface to the actual content, I found nothing to reassure my trembling stomach—even in the less overtly challenging short stories, I found the neurotic aggression overwhelming, overpowering. I moved on and found work to read that didn’t make me physically ill.

A few years later, a film about the cartoonist himself changed all of this. Crumb, a 1994 documentary directed by Terry Zwigoff, transformed Robert Crumb’s work permanently for me, by providing context, nuance and even ambiguity to work that had up to that point seemed alien and severe. The movie opens with gentle upright piano music and a close-up shot of a sculpted, hand painted statue of a woman’s muscular butt, and in a slow, shaky pan takes in row after row of wooden spools to which faces have been elaborately, lovingly drawn, remarkable objects that, it slowly becomes clear, seem to have no practical or commercial purpose. From the very first shot the film suggests that Crumb creates because he must. His artwork is a need, the spools say, open-mouthed, eyes agog. The shot continues, and lap dissolves into a pile of sketchbooks and records, and finally Robert himself, back to us and facing his stereo, knees to his chest, rocking slowly to the music.

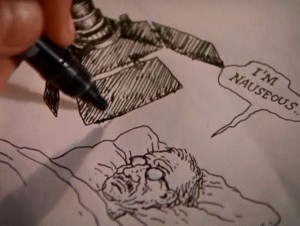

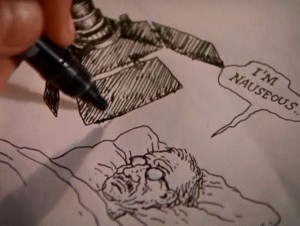

Cut to a drawing, and a hand with brush moving rapidly across the surface of the paper. “If I don’t draw for a while I get really crazy. I start feeling really depressed, suicidal.” These are Crumb’s first words in the film, delivered in a quiet, distant voice. “But sometimes when I’m drawing I feel suicidal too.”

“What are you trying to get at in your work?” someone, presumably Zwigoff, asks off-mic.

“JESUS,” Crumb says, suddenly animated. “I don’t know.”

Robert Crumb’s drawings are unflinching in their taut, sweaty grotesquerie, but the man himself flinches—he laughs nervously, stutters, cringes, equivocates.

He continues. “I don’t work in conscious messages. I can’t do that. It has to be something that I’m revealing to myself when I’m doing it, which is hard to explain. Which means that while I’m doing it I don’t know exactly what it’s about. You just have to have the courage or the… to take that chance. What’s gonna come out of this? I’ve enjoyed drawing, that’s all. It’s a deeply ingrained habit, and it’s all because of my brother Charles.”

Because of the powerful presence of his brothers, particularly Robert’s older brother Charles, the movie almost inevitably focuses on Crumb’s childhood, seemingly the source of both his obsessions and prodigious skill. By both their accounts Charles forced Robert to draw comics with him from a very early age, and was a domineering and seemingly crazed and competitive presence in young Robert’s life. Despite appearing for what probably amounts to about twenty minutes of screen time, Charles dominates the film, an intelligent, witty and doomed ghost of a man who seems in a way to have already passed on. So much of his life seems to be over, so many of his desires extinguished, that it seems inevitable that he will not last the duration of the movie.

We see examples of Charles’ and Robert’s comics from their childhood and teenage years, and get a glimpse at how these two remarkable young talents developed in parallel. Robert discusses his interest in other forms of art, and how it was his brother’s dogged persistence that kept him making comics, that in fact, it’s his brother who he still thinks of as his audience when he’s creating comics.

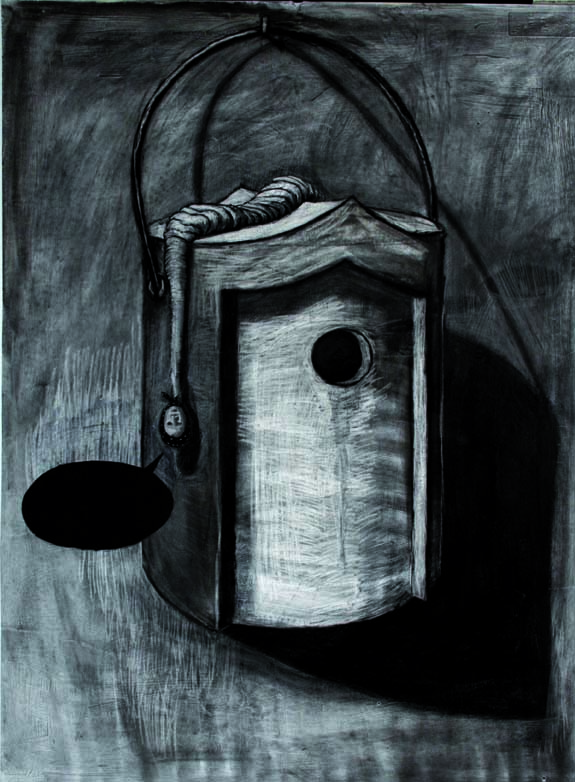

Young Charles’ work is truly remarkable, the work of someone who’s internalized at a very young age a whole host of cartooning skills and already developed his own visual style. But as Robert narrates the work chronologically, we slowly see that something seems to have gone awry in Charles’ mind. His style blossoms slowly into a collection of strange, grotesque visual tics, and pictures give way to more and more words, at first a rush, and then a torrent, panels and finally pages dissolving into microscopic scribble. And then, finally, his marks are nothing but scribble at all—content-less, without thought, finally, just tic. We watch as Robert flips through page after page of his brother’s illness made physical via pen and paper.

In the movie Charles serves as a harrowing parallel to his younger brother, a brilliant young cartoonist turning ever more inward, until there’s no communication left, no outside at all. He is the brother that could not escape the orbit of his childhood, who was unable to find a way to free himself from whatever it was that held him in thrall for so long.

What type of shared experiences shaped these three brothers? The movie hints at the edges—an abusive, withholding father, a mother who was either mentally ill, a drug user, or possibly both; but it presents no easy answers to these questions. What it does do, however, is provide a context for even the most extreme of Crumb’s works, and present a compelling argument for a man being saved by his art. Is it possible, the movie invites us to ask, that the difference between Robert and his brothers is that Robert found both release and escape?

Context also comes from the aesthetic decisions by Zwigoff himself. An early sequence of some of Crumb’s most violent, arguably mysogynistic drawings is accompanied by a haunting, keening voice, backed only by a circular, searching guitar and a blanket of hiss and pops. It is a song of “calamitous loss,” as Robert said earlier, and to hear such a song as the camera slowly pans and zooms across the twitchy surface of the drawings changes the experience of the drawings themselves from one of naked animal aggression to one of bewildered, pained loss. Where have these thoughts come from? the music seems to suggest. What has happened to this man?

Through its use of music and its austere, uncluttered editing and cinematography, the movie has great rhetorical power, great enough to reframe and even change the art that is ostensibly at the center of the film itself. A sequence mid-film presents an Angelfood McSpade strip with no narration, accompanied solely by a jaunty piano ditty that helps create a satirical tone that might be more arguable or problematic without the aural reinforcement.

The film also gives significant screen time to Crumb’s detractors, a strategy that defuses some of the uncomfortable edge of the work presented, which has the curious effect of allowing the viewer, or more specifically this viewer, to take his side again. Objections stated, points duly noted, we can return to the man himself and his obvious, almost palpable, need to create his work.

And that naked need, and the remarkable story of his brother Charles, are the reasons I’ve returned to Crumb so often, why despite a host of reservations, I showed the film, admittedly highly-edited, to my high-school cartooning class. Because Crumb is, in a winding, fractured, way not just the story of an artist, but a portrait of a survivor.

______________

Update by Noah: This post is loosely affiliated with an ongoing roundtable on R. Crumb and race.

In an pre-publication

In an pre-publication  Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form.

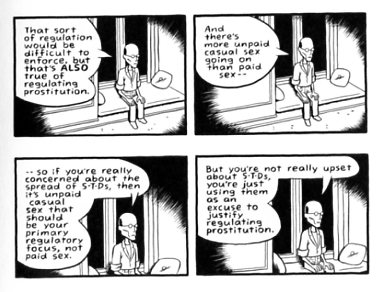

Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form. Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).

Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).  Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement.

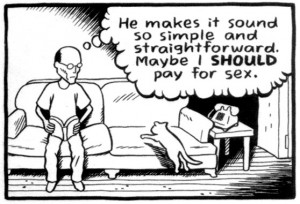

Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement. And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.

And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.  One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book,

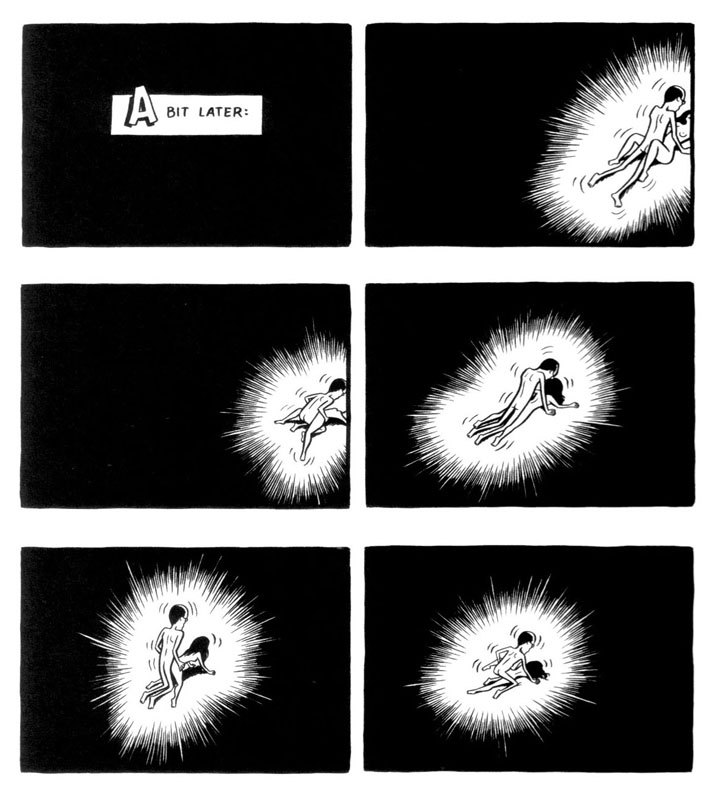

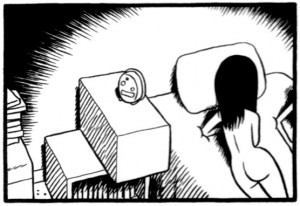

One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book,  As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.