How common are three-dimensional female characters in American superhero comics? I’m spectacularly unqualified to answer that question, since I read very few contemporary superhero comics, but I’m worried that the continued viability of sites like Gingerhaze’s Hawkeye Initiative and Heidi MacDonald’s Brokeback Tumblr means that most comics continue to be sexist junk. One series that I’ve kept up with, however, that doesn’t get enough credit for its cast of active, intelligent females, is B.P.R.D., written by Mike Mignola and John Arcudi, and currently drawn by a rotating group of artists, including Tyler Crook, James Harren and Laurence Campbell.

B.P.R.D. is a spinoff of Mignola’s Hellboy title, and chronicles the adventures of agents who work for a U.S. government organization that battles occult menaces. (“B.P.R.D.” stands for “Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense.”) The agents are a mix of characters with special abilities, like the aquatic Abe Sapien and the ghostly Johann Kraus, and non-superhero grunts just doing their jobs. B.P.R.D.’s premise isn’t innovative, but there’s a lot right about the follow-thru: Arcudi writes terse, realistic dialogue, Mignola and Arcudi’s soap-opera plots deliberately and suspensefully reveal information about their characters and their increasingly bizarre world, and the art, always competent and legible, is sometimes magnificent, as in the three pages by Gabriel Bá and Fabio Moon that open B.P.R.D.: Vampire #1 (2013).

Script by Mike Mignola, Gabriel Bá and Fabio Moon.

Art by Bá and Moon.

Out of context, these images echo Dario Argento’s approach to horror violence, where tortured and murdered women become an aestheticized misogynist spectacle. But B.P.R.D. is more complicated than that. The bodies drifting downstream have been killed by two ferocious female vampires, who torment a male agent, Simon Anders, throughout three mini-series, 1947 (2009), 1948 (2012) and Vampire. (The female vampires operate like film noir femme fatales: they’re evil and defined by their sexuality, but they’re also powerful and vibrant.) Further, in B.P.R.D. violence against men is just as common as violence against women: the first issue of B.P.R.D.: Monsters (2011), for instance, ends with a money shot of a gutted male torso missing its arms and legs. Most importantly, however, is the fact that Mignola and Arcudi write some of the most compelling female characters in all of comics, and for me that offsets the series’ gender-indiscriminate violence.

Before I discuss these characters, though, I want to be clear that my praise for some of B.P.R.D.’s female characters isn’t an unqualified rave for the series as a whole. I agree with the critical consensus that B.P.R.D. has dipped in quality since the departure of artist Guy Davis in 2011. One example of this critical consensus is the Comic Books Are Burning in Hell podcast on “The Long Death” storyline, where Chris Mautner, Joe McCullough, Matt Seneca and Tucker Stone point out that after two decades as the best superhero-comics line, the Mignolaverse has begun a decline precipitated by the replacement of Davis with less accomplished artists (especially Crook) and overproduction of both the main B.P.R.D. book (now monthly) and various spinoffs (Abe Sapien, Lobster Johnson). At its height, B.P.R.D. was sensational. The run from 2004 to 2010 (essentially the material collected in volumes two through four of the Plague of Frogs hardcovers) is my second-favorite genre comic ever, edged out by my favorite Lee/Kirby Fantastic Fours, but it’s currently not at its best.

Even when it was the best comic book at the shop, however, B.P.R.D. included plots that were occasionally problematic in their treatment of gender issues. You’d expect Liz Sherman, a firestarter who was part of Mignola’s original B.P.R.D. team with Hellboy and Abe Sapien, to be the title’s strongest, most independent female character, but not so: through much of the Plague of Frogs issues, her consciousness is invaded by a Fu-Manchuesque mystic named Memnan Saa, in a grindingly prolonged mind-rape that was handled with more energy and comparatively merciful brevity by Chris Claremont and John Byrne in their X-Men issues. (There’s the queasiness of “mind-rape” itself, and then the fact that it happens mostly to comic-book females: the only example of a male character being mind-raped by an invasive female consciousness is in the aforementioned B.P.R.D.: Vampire series, where Simon Anders is possessed by the spirits of the two vampire sisters.) My ability to identify with Liz, then, and admire her strength and power, was problematized by the way Mignola and Arcudi defined her, over a period of years, as Memnan Saa’s victim.

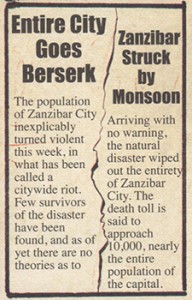

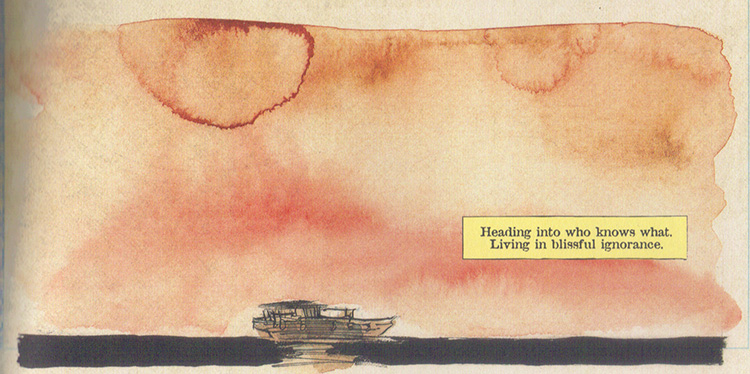

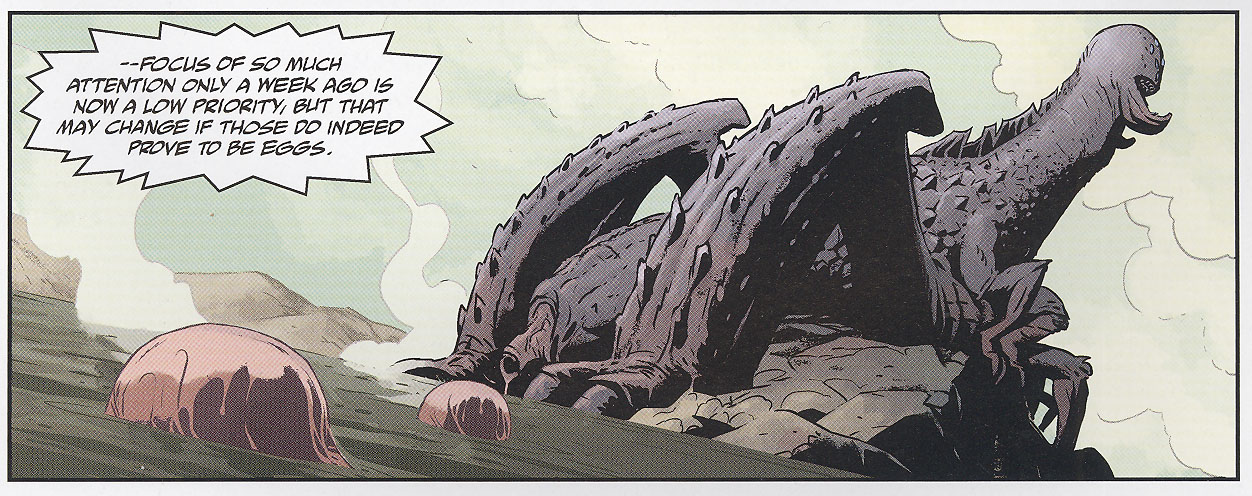

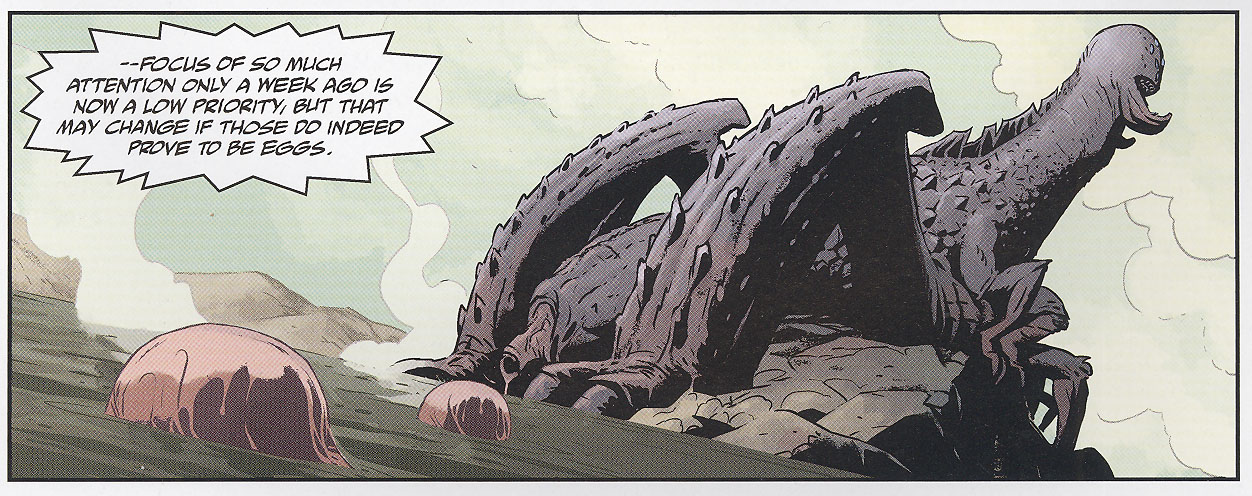

Further, the recent B.P.R.D. comics have been subtitled Hell on Earth, to show how Mignola, Arcudi and company have moved their fictional universe close to Armageddon. Chicago is infested by monsters, Houston is destroyed by a massive volcano, and the mantra for the Hell on Earth publicity is Mignola’s pitch that he and his collaborators are “breaking stuff we can’t ever fix.” Another troubled locale is California’s Salton Sea, where a giant creature stood immobile for a year, exhaling gases that changed humans into monsters, before she started laying eggs:

From B.P.R.D. #105 (HELL ON EARTH: A COLD DAY IN HELL, 2013).

Script by Mike Mignola and John Arcudi, art by Peter Snejbjerg.

In recent issues of B.P.R.D., both Abe Sapien and the precog teenager Fenix have traveled, separately, to the Salton Sea, where they encountered religious cults sprung up around the eggs. This monster/egg plot remains unresolved, though I’m worried that it will become an expression of what Barbara Creed calls the monstrous-feminine. Writing in the psychoanalytic theoretical tradition, Creed argues that numerous movie monsters—Samantha Eggar and her throbbing external wombs in David Cronenberg’s The Brood (1979), the egg-laying homicidal extraterrestrial in Aliens (James Cameron, 1986)—express a deep-seated patriarchal horror of female biology: giving birth is disgusting, women are disgusting because they give birth, and the Salton Sea monster might be another oblique metaphor for male revulsion towards female bodies and reproduction. I actually like body horror, and The Brood, and Aliens, but I hope Mignola and Arcudi take their egg-laying plot in a less predictable and sexist direction.

One more caveat: virtually no female creators have worked on Mignolaverse titles. The covers for the two-issue Pickens County Horror arc (2012) were drawn by Becky Cloonan, and one variant cover for The Dead Remembered (2011) was by Jo Chen, and that’s it. Three covers. (If I’m wrong about this, please correct me in the comments.) This isn’t an unusual situation in superhero / “mainstream” comics, but it is a shame, and I’d love to see Mignola and editor Scott Allie recruit talents like Colleen Doran and Pia Guerra (or maybe Renée French?) to contribute to the Mignolaverse.

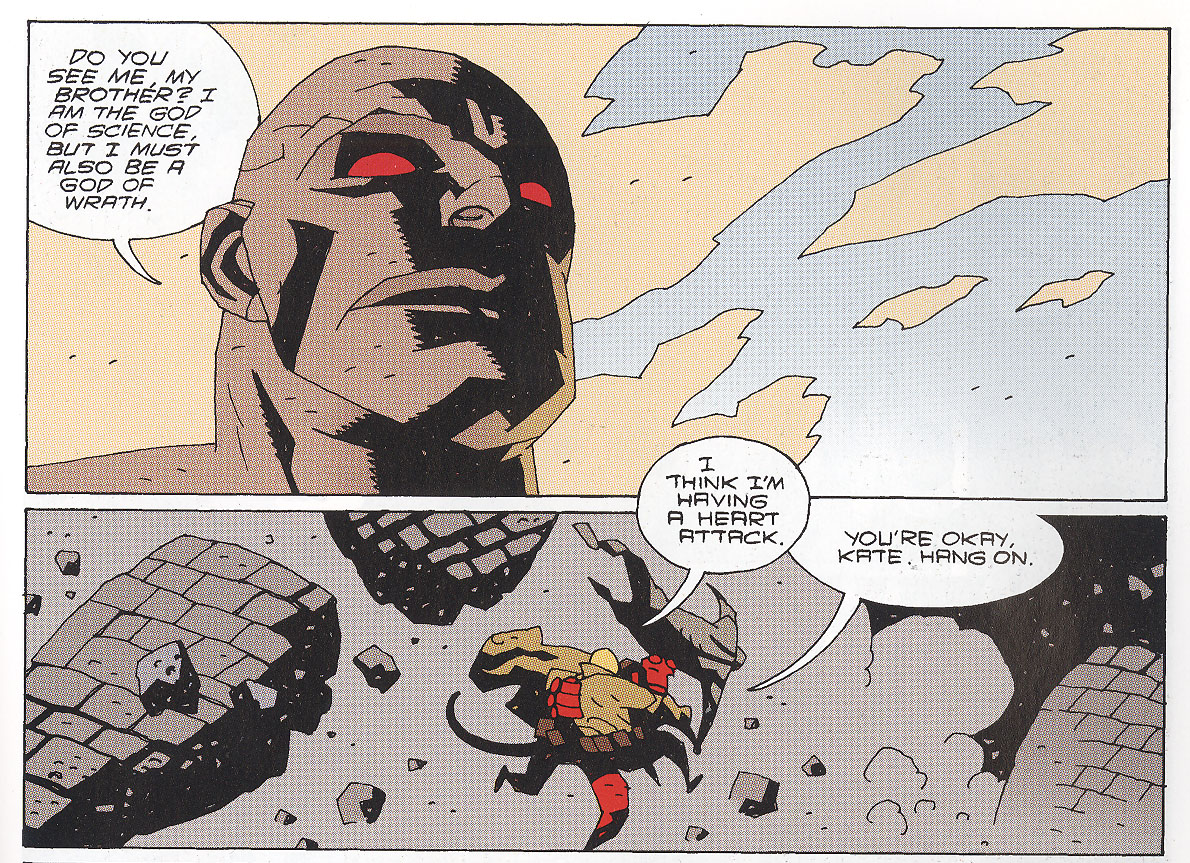

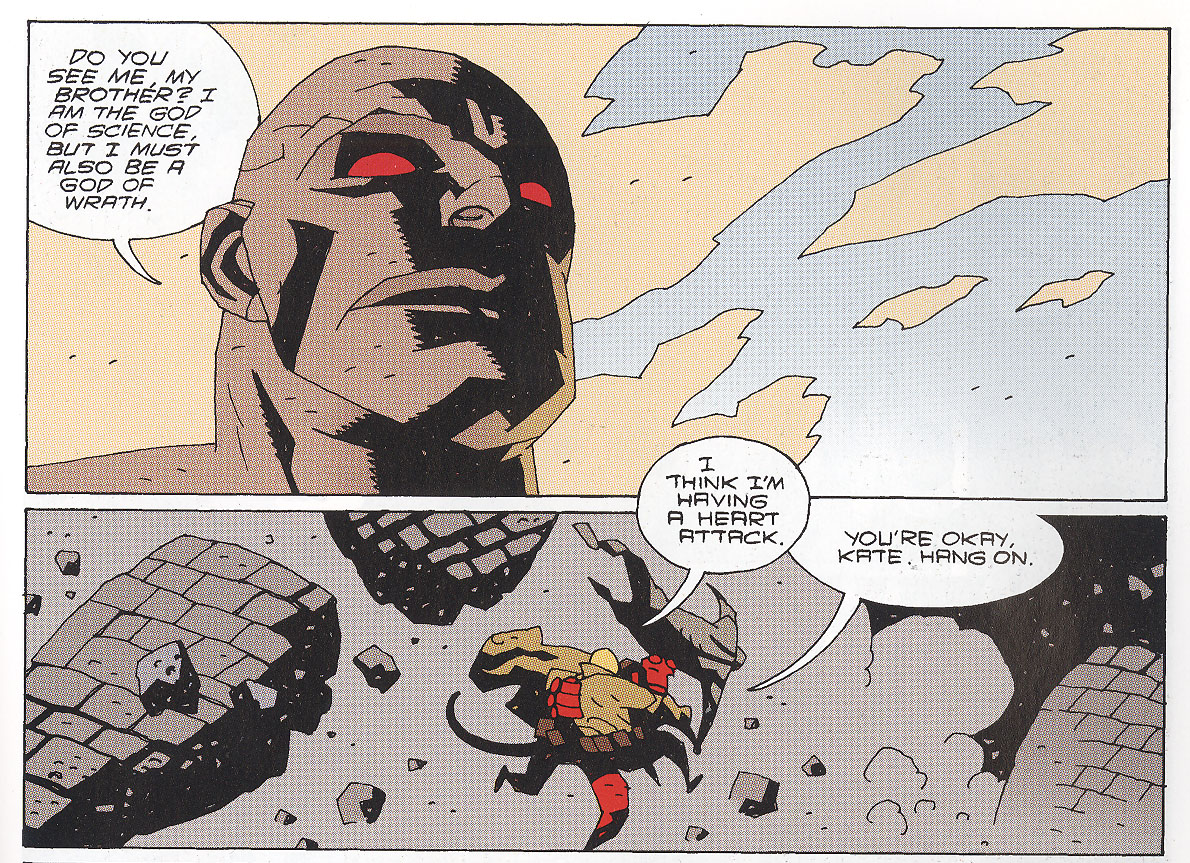

Despite my misgivings about some of the gender politics in B.P.R.D., I still want to compliment Mignola, Arcudi and Davis for their portrayal of Dr. Kate Corrigan, the leader of the B.P.R.D. since Hellboy quit the organization. Based in appearance on Mignola’s wife, Corrigan isn’t a firestarter like Liz Sherman, though her achievements (before joining the B.P.R.D., she was a tenured professor at New York University and an author of over a dozen books on the occult) seem superhuman. Despite her credentials, Dr. Corrigan’s introduction into the Hellboy world was inauspicious. In The Wolves of St. August (1994), she travels with Hellboy to a small Balkan village whose inhabitants have been murdered by werewolves; defined as a bookworm (“I know about this stuff, but…it’s different when you read about it”), she doesn’t do much except dump exposition, fall through an old castle floor, and watch as Hellboy beats up a badass werewolf. She reprises her spectator role in 1997’s Almost Colossus, as she’s taken captive by a homunculus (brother to Roger, another golem who later joins the B.P.R.D.) and saved once again by Hellboy.

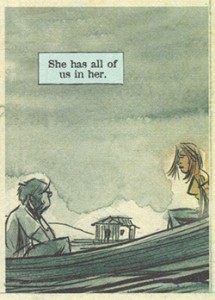

From HELLBOY: ALMOST COLOSSUS #2 (1997), Story and art by Mike Mignola

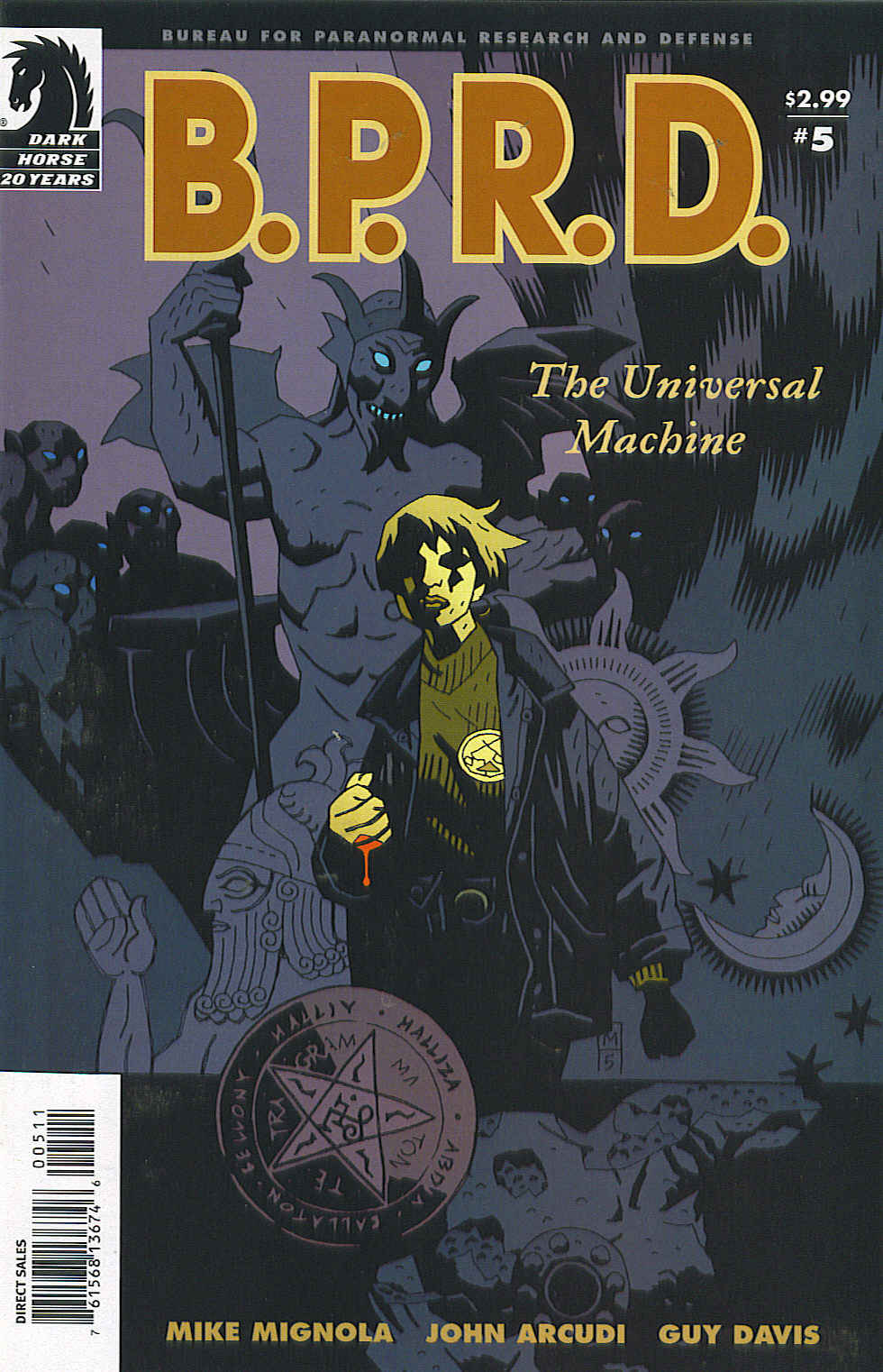

Corrigan is also a bit player in 2001’s Conqueror Worm, though she is enough of Hellboy’s confidant to support his decision to quit the B.P.R.D. In 2002, B.P.R.D. became its own title, and Hellboy’s absence allowed Corrigan and other supporting members to step into starring roles, as Corrigan did in my all-time favorite B.P.R.D. story, The Universal Machine (2006). Corrigan is kidnapped again, this time by the Marquis Adoet de Fabre, an ageless collector of occult memorabilia and owner of a rare book Kate and the B.P.R.D. need.

The cover for the final issue of THE UNIVERSAL MACHINE mini-series (2006). Cover by Mike Mignola.

In Universal Machine, Corrigan’s intelligence is treated as more than just ineffectual window-dressing, and she saves herself through her knowledge of history and through decisive action. (I’m being oblique because I don’t want to spoil the story.)

In the Mignolaverse, time passes at the same rate as in our own world. Many first-generation characters, like Hellboy, Liz Sherman, Abe Sapien and Kate Corrigan, are now in their 50s. Concurrently, Mignola and Arcudi juggle plots over extended periods of time, playing a “long game” that Chris Mautner (in the Comic Books are Burning podcast) compares to the deliberate pacing of Jaime Hernandez’s decades-long Locas serial. This is true of Corrigan’s gradual ascent into the B.P.R.D. hierarchy; she entered the series as a freelance consultant to the B.P.R.D., and over years of both story time and real time became the director of field operations. With the advent of Hell on Earth, Corrigan is now the leader and premiere strategist for the organization, as well as the liaison between the B.P.R.D. and more conventionally bureaucratic organizations like the United Nations. Sometimes Corrigan’s new job is played for laughs, as in this Guy Davis-drawn scene where Kate tries to dodge a U.N. functionary:

From B.P.R.D.: HELL ON EARTH: NEW WORLD #2 (2010).

Script by Mike Mignola and John Arcudi, art by Guy Davis.

More commonly, though, Corrigan suffers under the enormity of her responsibilities. Her dedication to the B.P.R.D. nixes any chance of a romantic relationship with German police officer Bruno Karhu, and she weeps over the decisions she makes that sacrifice the lives of field agents. Because I’ve been reading about Kate Corrigan for almost two decades now, I feel like I know her, and I sympathize with her.

Other readers might not find Kate Corrigan as interesting a figure, but part of her appeal to me is in how she revises the hero’s journey. My wife Kathy Parham is a fan of the Battlestar Galactica TV show (the 2004-2009 reboot), and when I told Kathy that I was writing about a Hellboy cast member who was a middle-aged woman and a leader without superpowers, she immediately compared Corrigan to Laura Roslin (Mary McDonnell), the Galactica character drafted as the President of Earth’s survivors. Kathy also directed me to an insightful LiveJournal posting about Roslin, where Galactica fan “larsfarm77” explains one element of Roslin’s attraction for female viewers:

I’ve watched a lot of science fiction. I can honestly say that I’ve never, ever, seen the classic hero arc played out for a woman, much less a mature one. How many times have we heard “it’s a coming of age story,” wherein [Luke, Harry, Frodo, Neo, Jake…] realize that they are so much more, that they have a destiny. Aided by his mentor [Obi-wan, Dumbledore, Gandalf, Morpheus, Grace…], he learns and grows, only to truly accept his role with the mentor’s death. And the woman’s role in all this: most often girlfriend, loving supporter of “the one.”

“Larsfarm77” then mentions that this aspiring hero/mentor pattern plays out in Galactica between two women (Roslin and religious visionary Elosha), a narrative trajectory that was “a long time coming.” Reading these words, I realized that I admire Corrigan for the same reasons–she’s an intelligent, mature woman who’s grown from being Hellboy’s helpless sidekick to the person most responsible for saving the human race–and I’m grateful to Mignola and Arcudi for writing her as a strong hero.

I suppose identification is easier where similarities exist between characters and readers. I like Kate Corrigan because she’s a middle-aged academic, just like me, but it’s possible to overstate the importance of these similarities. Storytellers can make me empathize with all kinds of different humans and creatures, and shift my identificatory attention between and among characters with frightening ease. (As a teenager, two works prompted me to identify across gender and other ideological boundaries: Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics [1965], which put me in the mind-sets of dinosaurs, mollusks, and colors, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho [1960], which effortlessly steered me to connect with both Janet Leigh’s petty larcenist and her murderer.) It’s identificatory fluidity and increased empathy that we want to encourage in readers of formulaic, sexist culture (e.g. superhero comics and Hollywood blockbusters, which are increasingly the same thing), and I like how B.P.R.D. sticks to the narrative/cultural formula of the mentored hero’s journey while abandoning much of the sexism. Any comic that encourages superhero fans, most of whom are male, to identify with an adult, normal-looking, smart, woman like Kate Corrigan is a comic I’m glad to read.

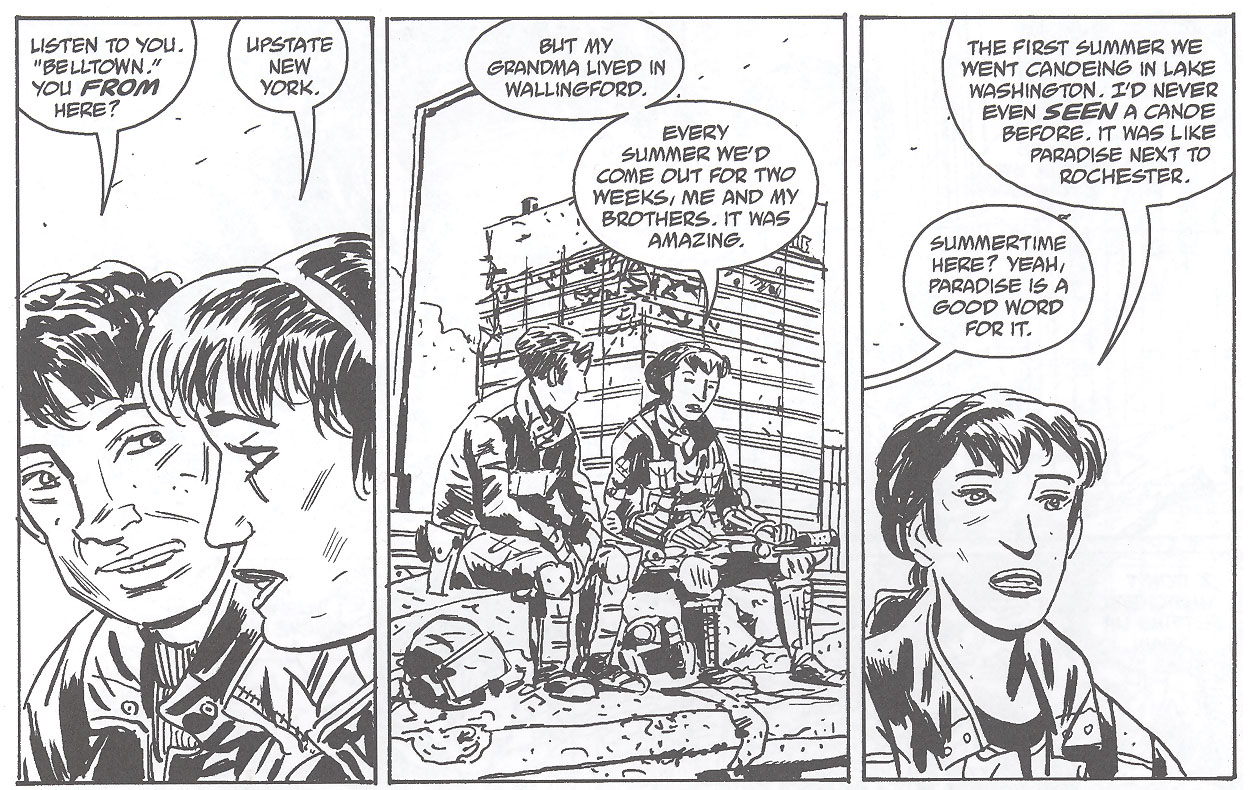

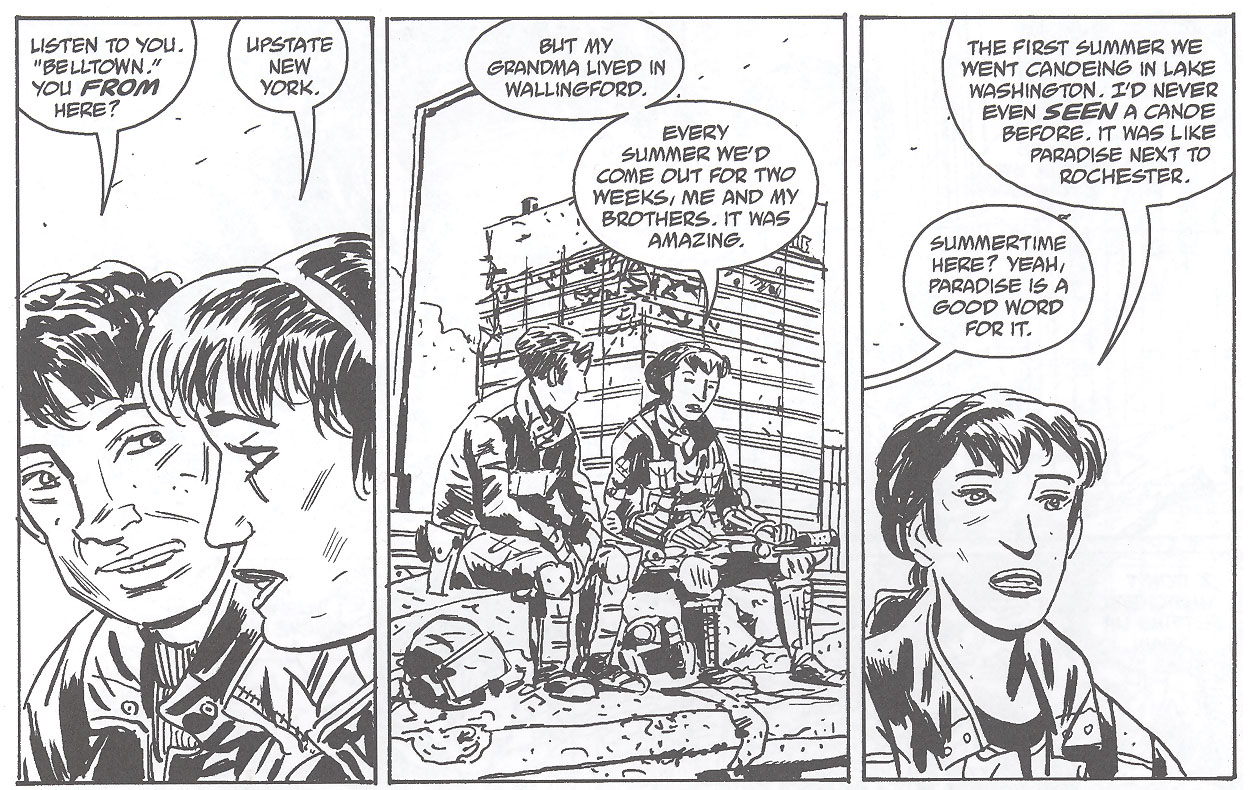

Recently, Mignola and Arcudi have introduced other, non-superpowered females into B.P.R.D., and snapped them into trajectories designed to grow them into central characters, just as Corrigan evolved from a victim to a leader. One such character is Carla Giarocco, introduced into the comic in 2011 through both a normal walk-on and an ominous premonition. We first see Giarocco in Hell on Earth: New World, as a field agent who phones Corrigan and inadvertently reveals to Kate that Abe Sapien has gone AWOL into the Canadian woods. Among the non-superheroes now prominent in B.P.R.D., including agents Gervesh, Tian and Vaughn (all of whose histories are nicely summarized in an essay by Mark Tweedale), Giarocco has been given the most backstory. In a black-and-white freebee distributed at the 2010 Emerald City Comicon, she reveals to a Seattle cop that she grew up in Rochester, New York, and is married with a three-year-old son.

From B.P.R.D.: HELL ON EARTH: SEATTLE (2011).

Script by Mike Mignola and John Arcudi, art by Guy Davis.

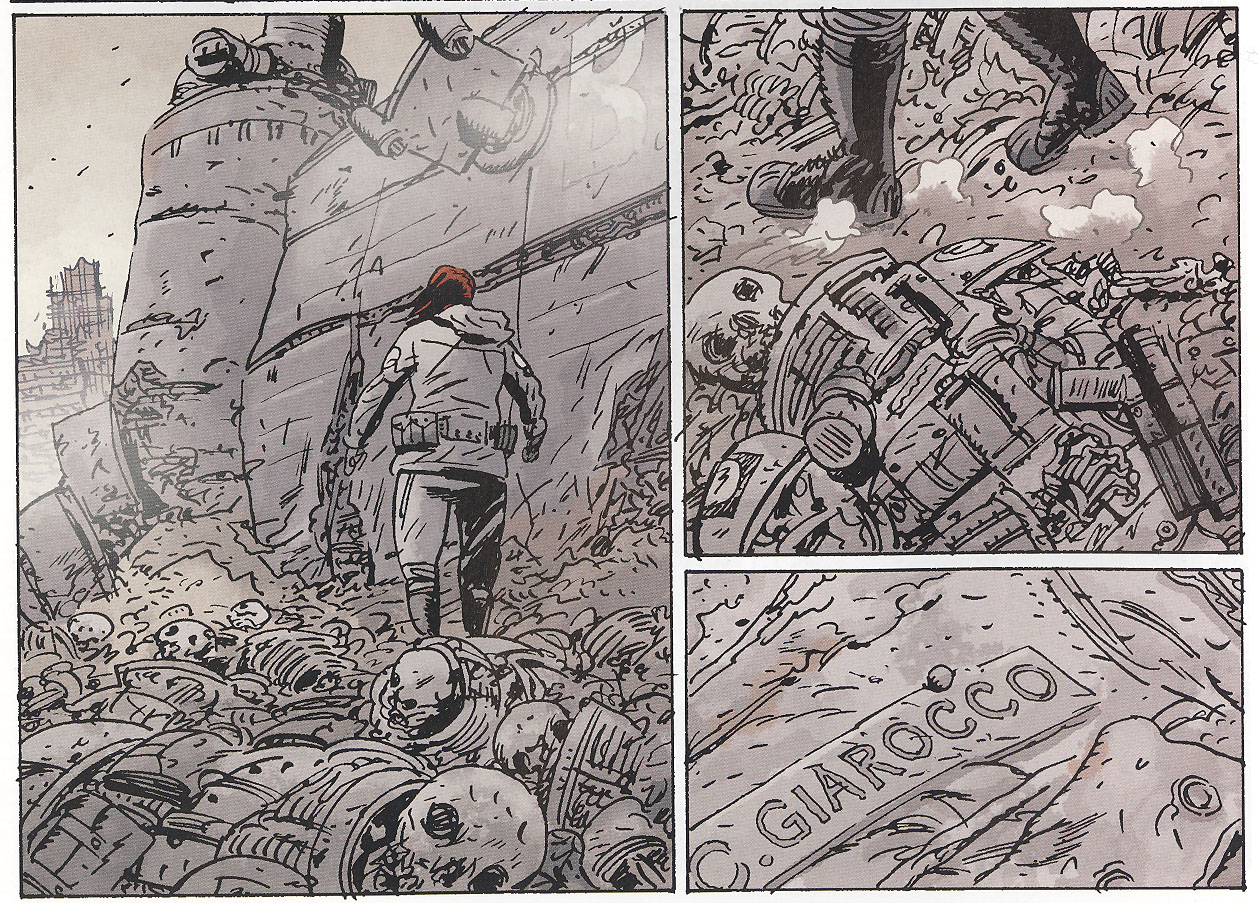

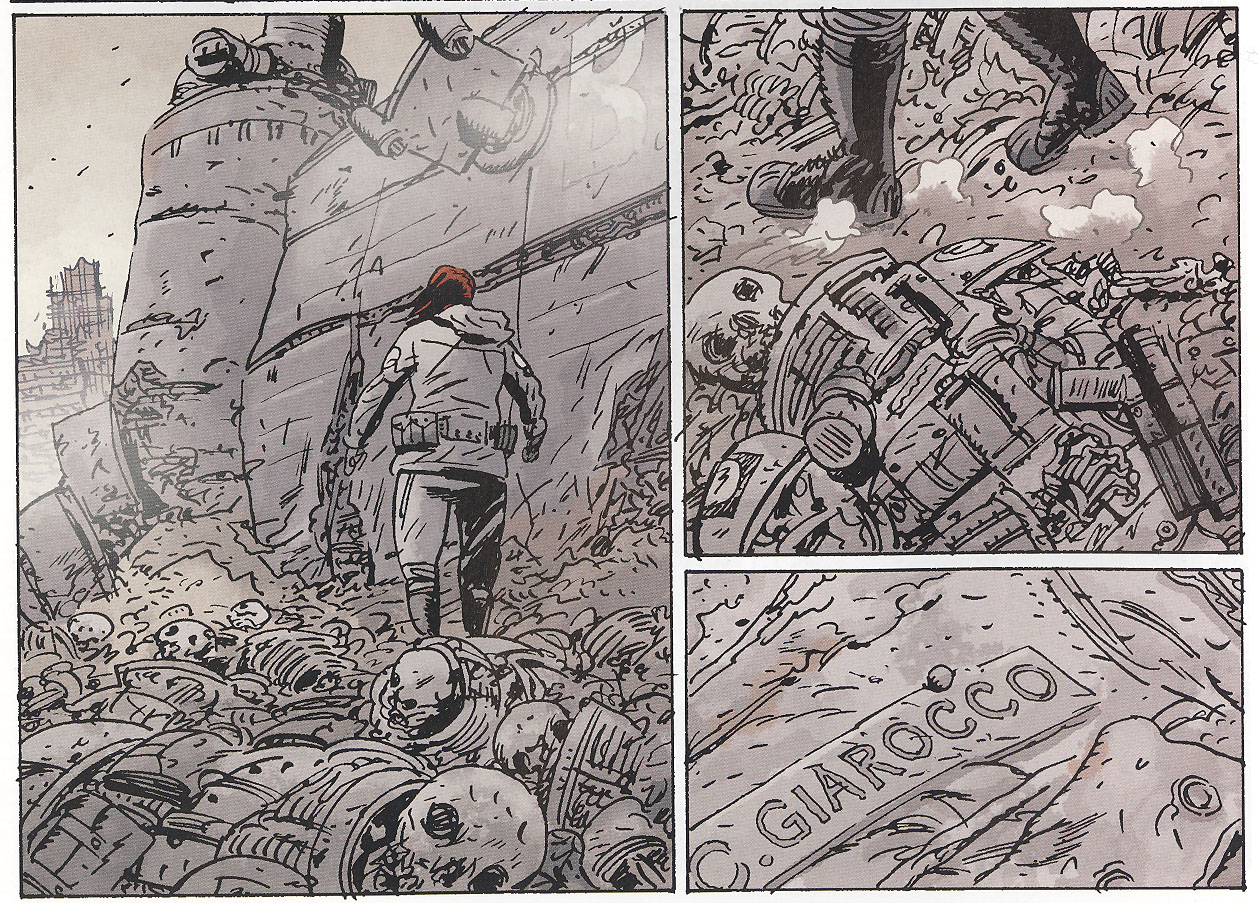

Giarocco also seems the toughest of the new crop of agents: she survives a fight against a blood-crazed were-jaguar (!) that eviscerates almost an entire BPRD battalion (see The Long Death arc, 2012), and she teams up with Russian director of occult operations Iosif Nichayko on a dangerous mission (see A Cold Day in Hell). In fact, the only thing poised to slow down Giarocco is a tragic, predestined fate. After Liz Sherman and the B.P.R.D. kill Memnan Saa, but before Giarocco enters the series, Saa’s spirit returns from the dead to show Liz a future world devastated by the Ogdru Hem, the Lovecraftian overlords of Mignola’s world, and their frog-like minions. Here’s Liz wandering around in Saa’s vision of catastrophe:

From B.P.R.D.: KING OF FEAR #4 (2010).

Script by Mike Mignola and John Arcudi, art by Guy Davis.

Carla Giarocco’s skeleton appears in B.P.R.D. before the live Giarocco does. We might try to write off this vision as a lie fabricated by Saa to punish Liz, but how do we explain the “Giarocco” nametag if neither of them know who Carla Giarocco is? Further, the zoom-in of the last panel is clearly for our benefit rather that Liz’s: we’re supposed to notice her name, and then fret as Giarocco joins the B.P.R.D. This reads as Mignola and Arcudi’s homage to other superhero teams with stories staged in the future tense–think of the “imaginary” Adult Legion of Superhero stories, or the X-Men’s Days of Future Past–and doesn’t auger well for Giarocco’s long-game future in the series.

Although she’s less important than Giarocco, my favorite of the Mignolaverse’s new female characters is Ashley Strode, who’s appeared in three B.P.R.D. comics, War on Frogs #3 (2009) and the Hell on Earth: Exorcism arc (2012). The four-issue War on Frogs series chronicles the day-to-day dangers and horrors B.P.R.D. agents experience as they murder the ambulatory frog-monsters who serve the Ogdru Hem. (War on Frogs isn’t a simple-minded action comic: Mignola and Arcudi establish in the fourth issue that the frogs have feelings and souls, and the B.P.R.D.’s purging of frog populations is a kind of genocide rather than just a herd-thinning.) In War on Frogs #3, Ashley Strode is a young agent reminiscing about how she’s tried to be friendly with Liz Sherman, especially during a mission to a supposedly abandoned frog site. Although much of the narrative is a flashback from Strode’s memory, our emotional center is Liz: we feel Liz’s numb horror as she repeatedly ignites and decimates nests of frogs, and the issue ends with images from Liz’s point-of-view, as we see her isolation (a symptom of which is her aloofness toward Strode) when her consciousness is taken over by Memnan Saa. In this story, Strode is less a fleshed-out character than a pretext for human-frog violence and an exploration of the consequences of Liz’s mind-rape.

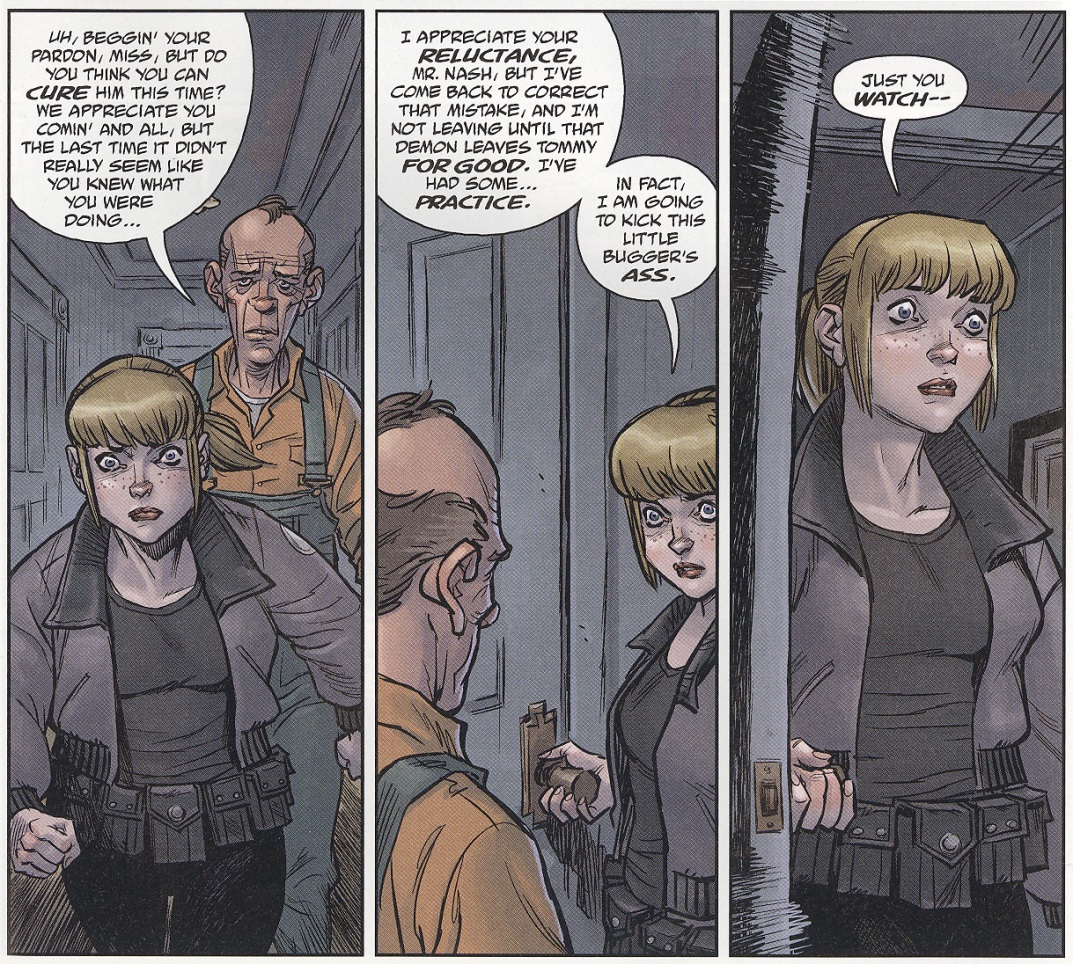

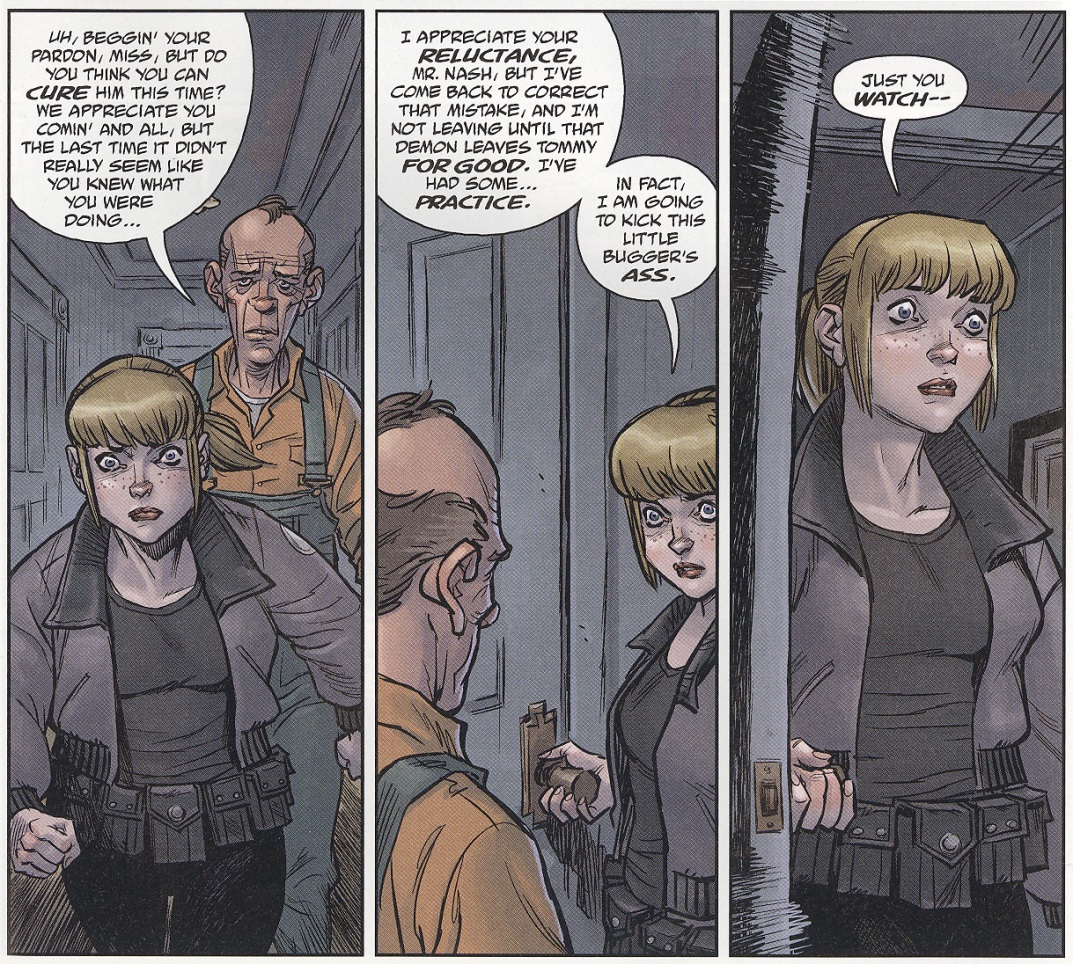

We learn more about Strode in Exorcism, a two-issue tale written and drawn by Cameron Stewart, best known for his Eisner Award winning webcomic/graphic novel Sin Titulo. (Mignolaverse editor Scott Allie, presumably in consultation with Mignola and long-term collaborators like Arcudi, sometimes give characters to specific artists: stories starring the B.P.R.D. vampire agent Simon Anders are now reserved for Gabriel Bá and Fabio Moon, and Ashley Strode for Cameron Stewart.) Initially in Exorcism, Strode freezes when confronted with a possessed young boy, and learns how to handle occult situations only after she battles a demon on the “spiritual plane” alongside a legendary Catholic exorcist. Stewart draws Strode as young, perky and cute–not to Lolita-ize her, but to emphasize her status as a B.P.R.D. greenhorn. By the end of the story, Strode is contemplative in the face of the apocalypse, yet confident enough to return and confront the devil inside the little boy.

From B.P.R.D.: HELL ON EARTH: EXORCISM #2 (2012).

Script by Mike Mignola and Cameron Stewart, art by Stewart.

I don’t know when Cameron Stewart will do another Ashley Strode story. In a Twitter thread from October 2013, Stewart said that he would no longer draw “sketches/commissions of characters that aren’t my own” at comicons, and indicated that this would keep him from drawing Strode. Maybe Stewart is moving in a more personal, creator-owned direction, and won’t return to B.P.R.D. I’d still like to read stories where Ashley Strode advances and matures as Kate Corrigan did.

Earlier, I typed the word “were-jaguar” and then flinched as I wondered what Domingos or Suat might think of the wholesale superhero-horror-genre-wallow of B.P.R.D. My comparison of Laura Roslin with Kate Corrigan might also put some readers off; perhaps the problem isn’t the absence of women characters in the aspiring hero/mentor formula, but the endless repetition of the formula itself. I’m not particularly interested in defending my pleasure in B.P.R.D., but maybe even people who hate superheroes can share my relief that the Mignolaverse has comparatively strong female characters rather than objectified toys and damsels in distress?