If you’re wondering why Johnny Depp has a dead bird on his head in the new Lone Ranger, look at Kirby Sattler’s “I Am Crow.” The painting is to Tonto as Keith Richards is to Captain Jack Sparrow. It also has as much to do with Native America as the Rolling Stones have with the 1700s Caribbean.

According to Sattler’s website, his “paintings are interpretations based upon the nomadic tribes of the 19th century American Plains.”If you think that means the model for or at least the subject matter of “I Am Crow” is a Crow Indian, think again. “I,” explains Sattler, “purposely do not denote a specific tribal affiliation to my paintings, allowing the personal sensibilities and knowledge of the viewer to create their own stories.”(Mr. Depp’s personal sensibilities, for instance, tell him the dead bird on his head likes peanuts.) Sattler’s website also notes that the sixty-three-year-old painter is of “non-native blood” and that he’s neither a “historian” or “ethnologist.” And yet his “distinctive style of realism” avoids being “presumptuous” by giving his work “an authentic appearance” but “without the constraints of having to adhere to historical accuracy.”

That makes Sattler a perfect source for Johnny Depp’s equally imperfect Indian fantasy. The actor may have a Cherokee or possibly Creek grandmother (how else to explain those cheek bones?), and he told Rolling Stone that hopes his portrayal of Tonto will “maybe give some hope to kids on the reservations.” His first Indian character was named “Nobody” in Jim Jarmusch’s 1995 Dead Man (a film I really really tried to like), which prompted Depp to direct himself in The Brave two years later. The film wasn’t released in the U.S., not even on video, so I’ll have to trust the IMBd summary:

“An unemployed alcoholic Native American Indian lives on a trailer park with his wife and two children. Convinced that he has nothing to offer this world, he agrees to be tortured to death by a gang of rednecks in return for $50,000.”

If you replace “gang of rednecks” with “American pop culture,” that’s a decent allegory for Tonto.

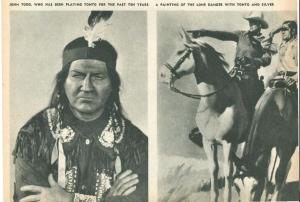

Depp’s performance is also based on Jay Silverheels, who played Tonto in the 50s TV show. He was born Harold Smith on a Canadian Mohawk reservation, but for some reason went with “Silverheels” when he moved to Hollywood. His performance in turn was based on John Todd, who voiced Tonto in the 30s radio show. Todd was 77 and the last original cast member when the show went off the air in 1954. He was also Irish, but was happy enough to play dress-up for publicity shots. The network replaced him for public appearances, and briefly on air too, but, the story goes, the college-educated Native actor refused to read Tonto’s ungrammatical lines, so Todd got the job back.

Tonto was originally Potawatomi, so he and his Michigan tribe (the program aired from Detroit) were a bit lost in the Southwest. Someone changed it to Apache, but Camp Camp Kee Mo Sah Bee, the summer camp the director visited as a kid, is a better designation. Tonto means “stupid” or “silly” in Spanish, but that might be coincidence. The writer just needed someone for the Long Ranger to talk to.

The same creative team gave the Green Hornet a chauffeur for the same reason. The Lone Ranger may look like someone grabbed a superhero, slapped a cowboy hat on his head, and dropped him in a Western, but the lines of influence run the other direction. The Lone Ranger premiered in 1933, five years before Superman hit newsstands. It was a hit, so when the radio station demanded another show like it, they just updated the formula. The 1936 Green Hornet is an urban Lone Ranger. His horse “Silver” morphed into the limo “Black Beauty.” His Indian sidekick transformed into an oriental sidekick (Kato’s ethnic designations make less sense than Tonto’s). The Hornet’s even a blood relative. His alter ego, Britt Reid, is the Lone Ranger’s great nephew. Britt’s father, the Ranger’s nephew, is Dan. John Todd voiced him too. The Shakespearean actor dropped Tonto’s broken English to record the elderly Mr. Reid into the same microphone.

But now the superhero influence really is reversed. Seth Rogen’s Green Hornet beat Armie Hammer’s Lone Ranger to theaters by two years, both fueled by the killing Marvel and Warner Brothers are making on their assorted Avengers and Justice Leaguers. Even Kirby Sattler’s interest in “the Indian” has more to do more with pop culture than “Indigenous Peoples of the Earth.” The crow Johnny plopped on his head is, according to Sattler, a source of power:

“Any object- a stone, a plait of sweet grass, a part of an animal, the wing of a bird- could contain the essence of the metaphysical qualities identified to the objects and desired by the Native American. This acquisition of ‘Medicine’, or spiritual power, . . . provided the conduit to the unseen forces of the universe which predominated their lives. . . when combined with the proper ritual or prayer there would be a transference of identity. . . .More than just aesthetic adornment, it was an outward manifestation of their identity.”

And that, Kirby, is what we folks of non-native blood call a superhero:

Any object—a lantern, a ring, a bat, even an initial—contains the symbolic essence of the superpowers identified with the object and desired by the alter ego. Once acquired, unseen forces of the multiverse predominate the lives of the wearer. When combined with the proper ritual or prayer (“Shazam!”), there is a transference of identity (“Hulk smash!”). More than adornment, the superhero’s costume is an outward manifestation of his identity.

I could quote some juicy bits from Michael Chabon’s “Secret Skin: an essay in unitard theory,” but you get the idea.

None of this is to say The Lone Ranger is a stupid movie. It’s more entertainingly silly than the black and white reruns I watched as a kid. I also attended “Indian Guides,” in which fathers and sons of my Pittsburgh suburb assembled plastic tomahawks and heard legends of “Falling Rock,” the mysterious brave whom yellow road signs warned drivers to beware. So my “personal sensibilities and knowledge” of things Indian is right up there with Sattler and Depp. (My novel School for Tricksters is about two fakes pretending to be Indians too, but we’re talking Lone Ranger right now.)

I do give director Gore Verbinski credit for framing the tale as a 1933 Wild West exhibit, a style of realism even less constrained than Mr. Sattler’s. Tonto, “A Noble Savage in His Natural Habitat,” is a magically talking mannequin. That almost but not quite makes up for the self-annihilating Comanche (Tonto’s latest tribe) who aid Manifest Destiny by declaring themselves ghosts and charging into the spray of Gatling guns. (Can you feel the hope surging through those reservation kids?) Tonto at least gets an upgrade from racially laconic sidekick to racially madcap mentor. He and Grasshopper Ranger romp across a cinematic West that owes less to John Ford than Wile E. Coyote. You’ll be amazed by how many CGI-ed train stunts Verbinski can cram into two and a half hours (longer if your theater’s projector overheats as ours did).

Verbinski also includes several werewolf-esque bunny rabbits, so there’s far far more whimsy in Lone Ranger than in the masked mayhem Warner Brothers or even Marvel Entertainment have been putting out. Superheroes are naturally Goofy Creatures best exhibited in a Habitat of Whimsy, so I applaud the Verbinki bunnies (they have fangs!). I would just tweak the latest Tonto by revealing him for what he’s always been. A deranged white guy pretending to be an Indian. Surely Gore and Johnny could mine some comic silver from that premise.