“Edward Said talks about Orientalism in very negative terms because it reflects the prejudices of the west towards the exotic east. But I was also having fun thinking of Orientalism as a genre like Cowboys and Indians is a genre – they’re not an accurate representation of the American west, they’re like a fairy tale genre.” – Craig Thompson, PopTones Interview, September 1, 2011

It’s easy to inventory my feelings about Craig Thompson’s Habibi. For well over a year, I approached its release with equal parts excitement and fear. The fear sprang from the 2010 Stumptown Comics Festival — held in Thompson’s hometown of Portland, OR near the completion of Habibi — as I sat in the audience of a Q&A session with him about the processes of publishing and creation. There he explained (as he has in many venues since) that Habibi was going to be an expansive book about Islam and the idea was birthed out a place of post-9/11 guilt he felt in reaction to America’s Islamophobic tendencies. Had he traveled much in the Middle East? No, except Morocco. Did he know Arabic? No, but he had learned the alphabet. At one point he actively said he was playing “fast and loose with culture” picking from here and there in order to tell his story as he saw fit. As I sat in the audience I saw red flags going up. I was about the spend a year abroad studying how The Adventures of Tintin is a Orientalist text precisely because Hergé rarely left the confines of Belgium while drawing the far off landscapes of India, Egypt, China, or made-up Arab lands like Khemed. And here was Craig Thompson some 80 odd years later, well intentioned, proposing a very similar project of creating a made-up Arab land of Wanatolia for the purposes of quelling his own guilt. What he called “fast and loose,” I called cultural appropriation.

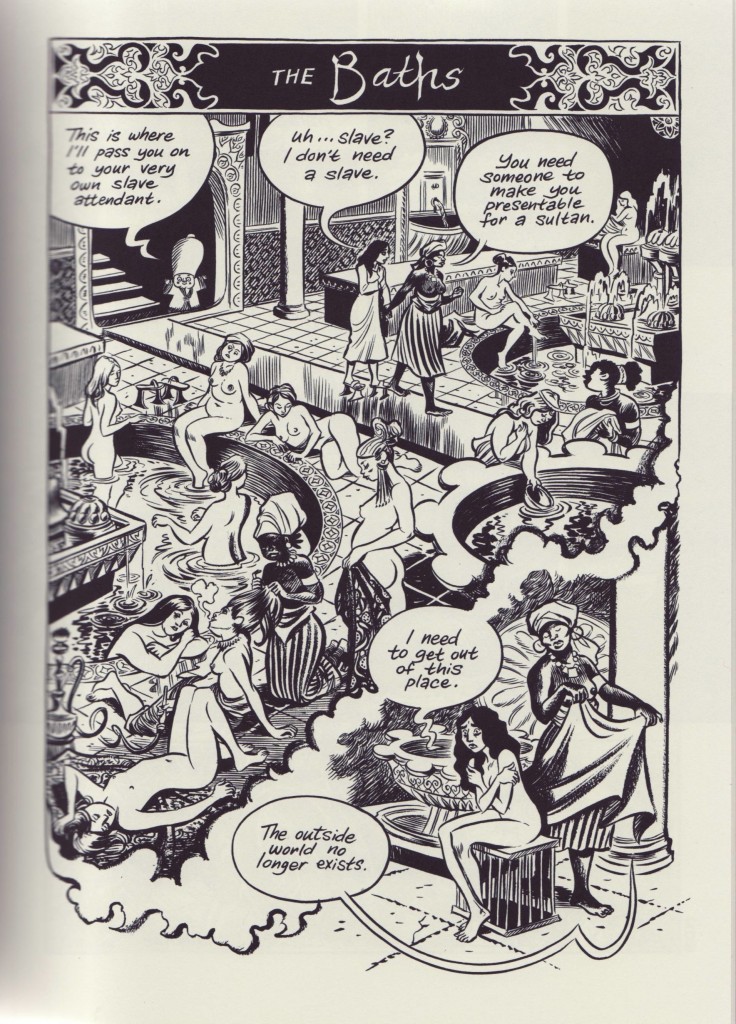

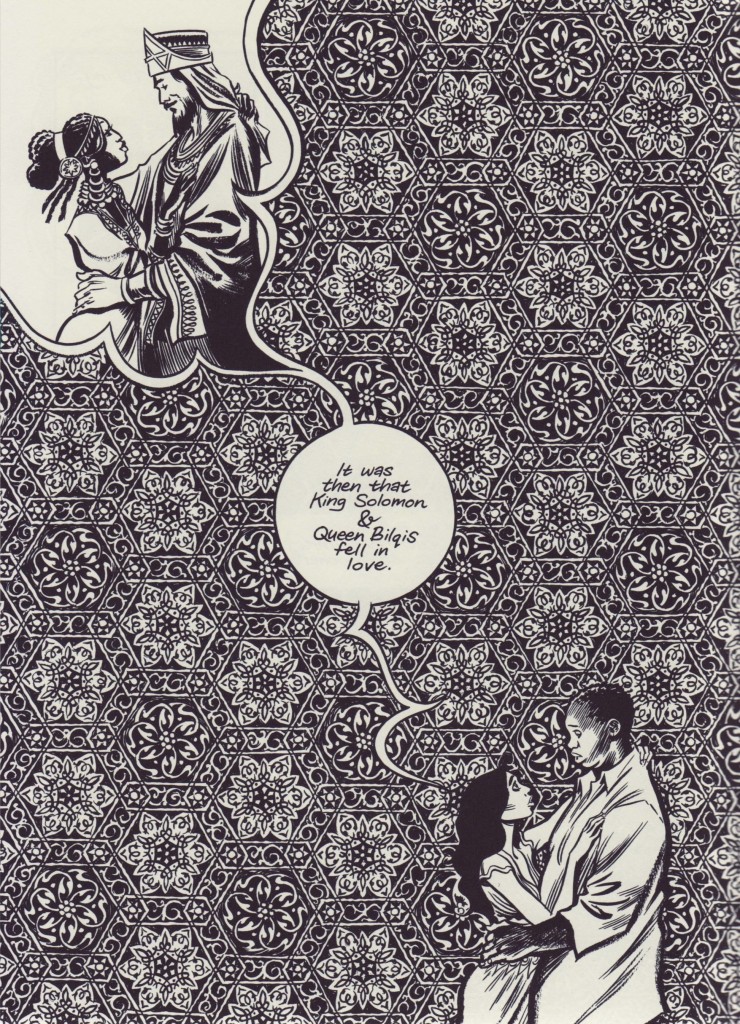

Habibi at its best and worst.

Now that the tome is here and I’ve had a chance to read it I feel no less nauseous or enthusiastic about the work that Thompson has produced. To be clear, Habibi is a success on many levels, but it also contains elements that are strikingly problematic through the lens of Orientalism. There are three key components to Habibi: Calligraphy and Islamic patterns, illustrated Suras from the Qur’an and Haddith, and a love story between the characters Dodola and Zam. On the first two counts, Thompson has more than excelled in creating a beautiful rarity for U.S. bookshelves. On the last count of the decades-spanning love story that Thompson has chosen to tell and the setting he has chosen to tell it in, I find that Habibi is a tragically familiar Orientalist tale that a reader can find in books by Kipling or many a French painter.

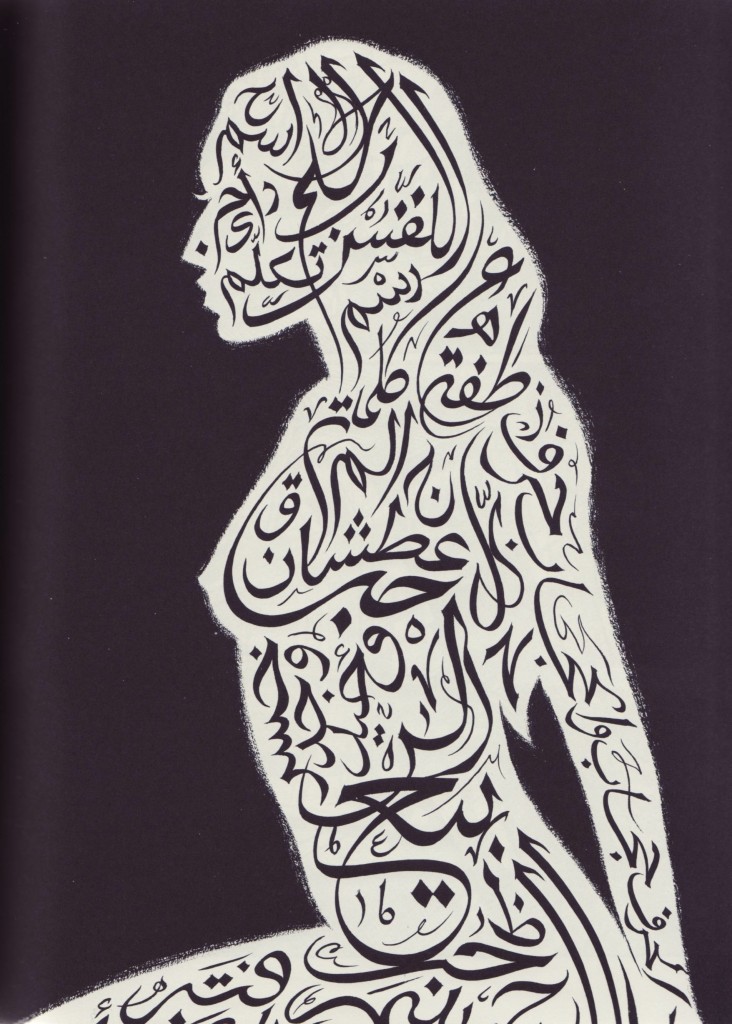

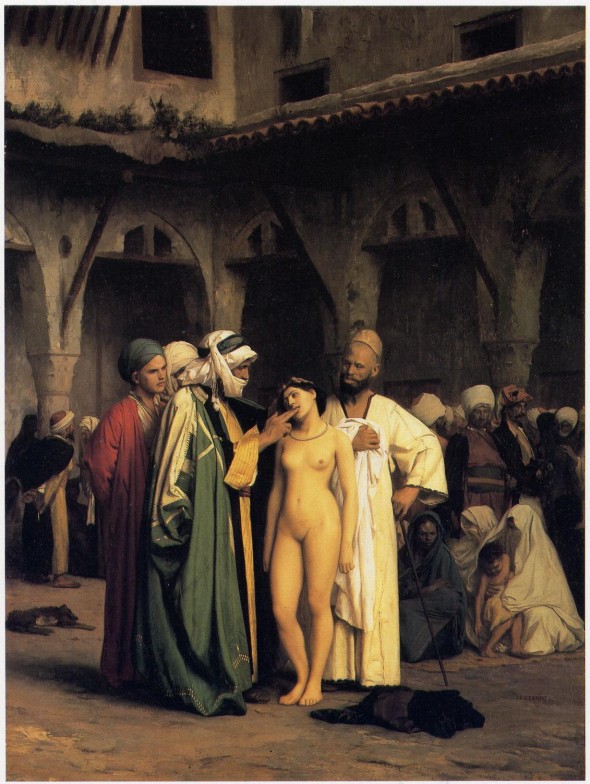

The Slave Market by Jean-Leon Gerome (1866)

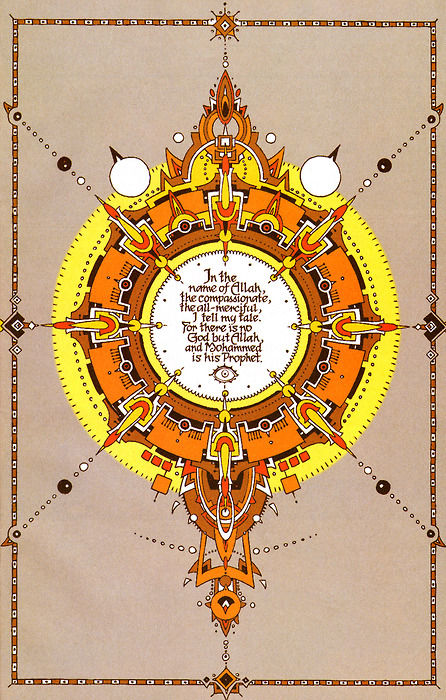

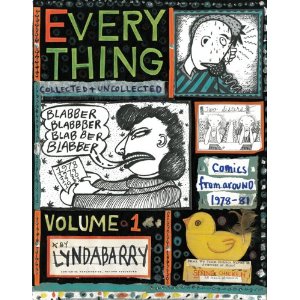

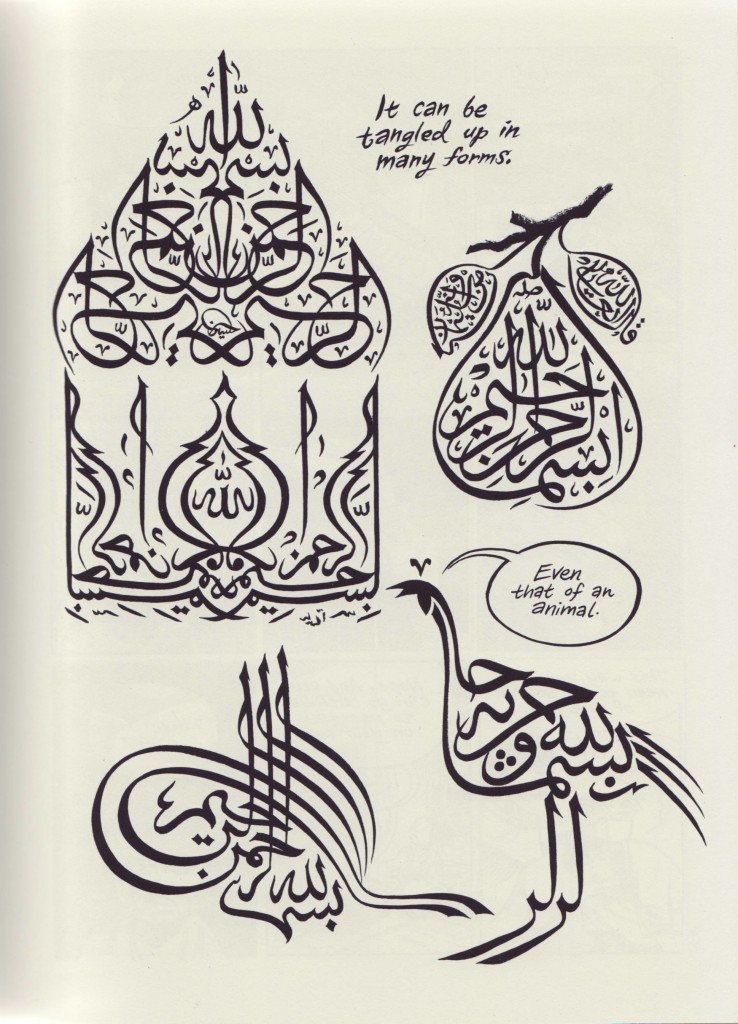

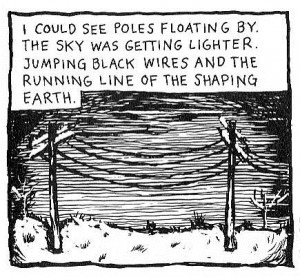

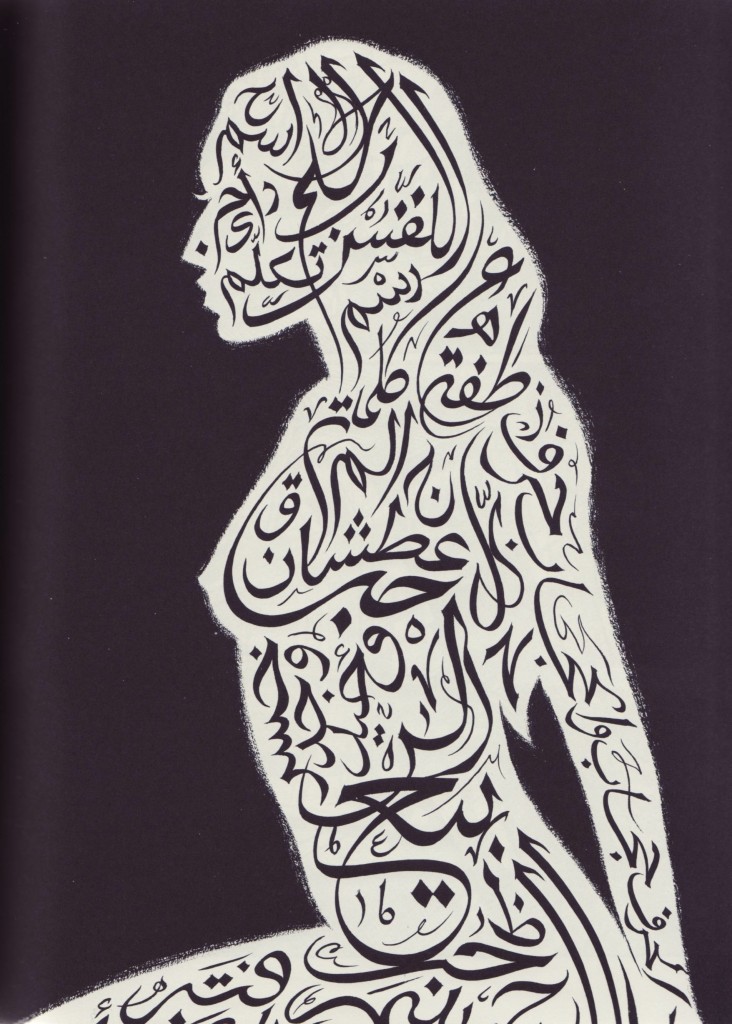

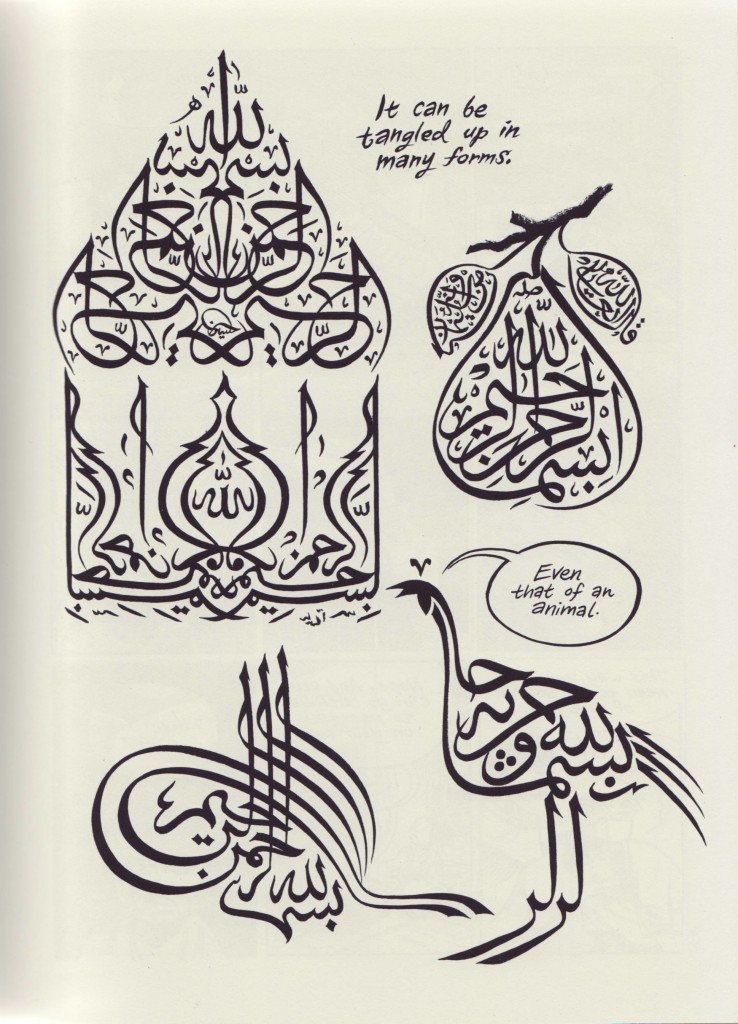

I will get to how the book fails to escape many classic Orientalist trappings soon, but first let’s discuss what Habibi gets right. The good is found foremost in the calligraphy and geometric patterns Thompson employs throughout Habibi. Given the technical skill and confidence Thompson uses when writing in Arabic, it is really unbelievable that he doesn’t actually know the language. Here is a prime example from early in the text:

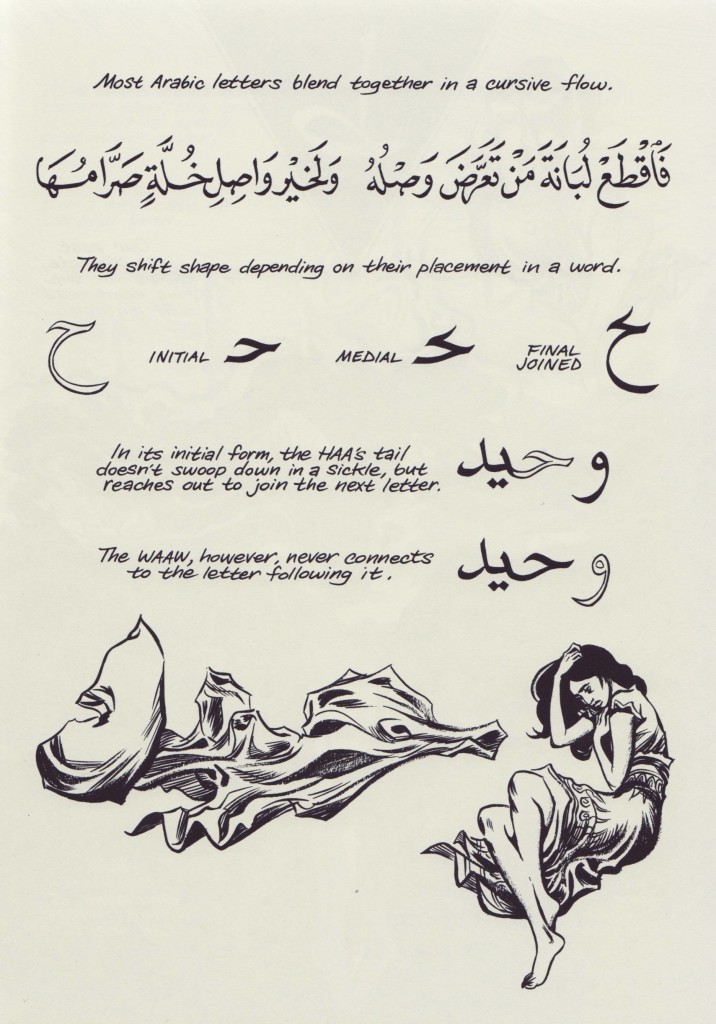

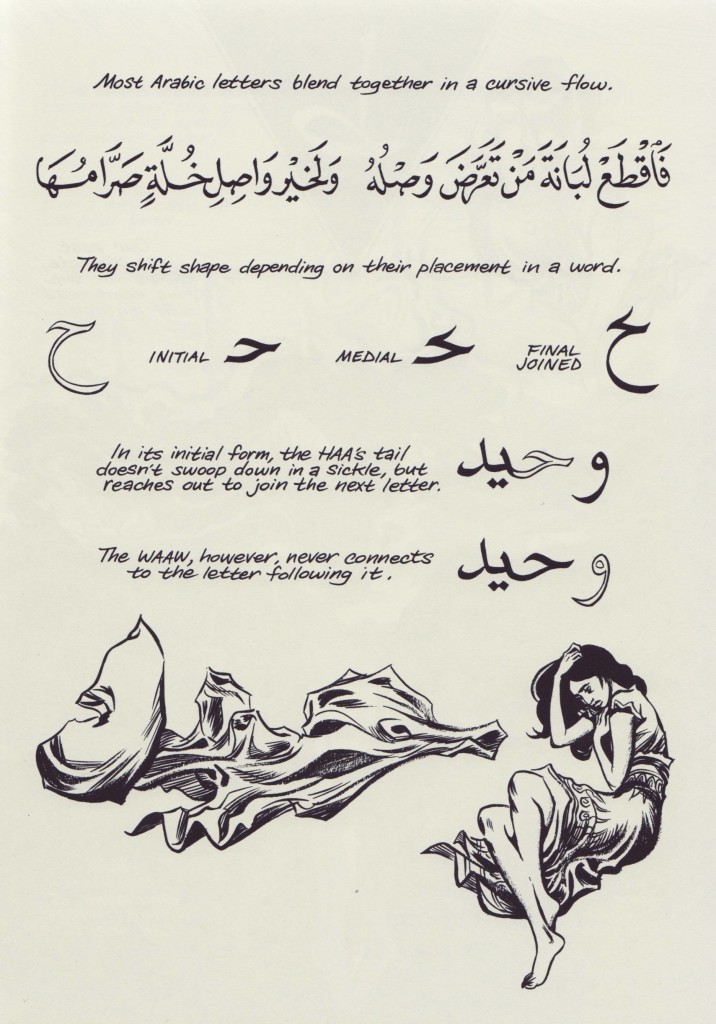

From any perspective this is stunning artwork. Through Dodola’s first husband, a scribe, Thompson creates a space to explore the beauty of calligraphy in the larger narrative. Therefore, on a meta-level, Habibi is a format for Thompson to practice calligraphy: an art form that lends itself well to the loose expressive brush line he made iconic in Blankets. As a reader, Thompson’s joy in learning the Arabic alphabet and how it can work simultaneously as a symbolic and literal art form comes across. His perspective as a non-native speaker with a strong artistic background works towards him making interesting connections about Arabic in Habibi:

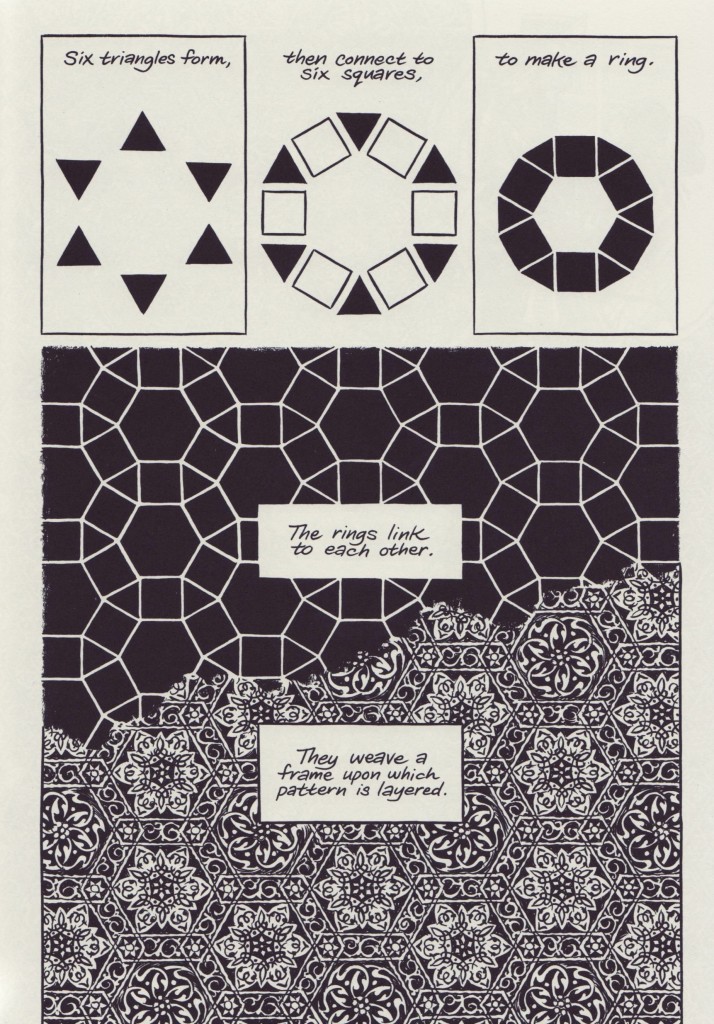

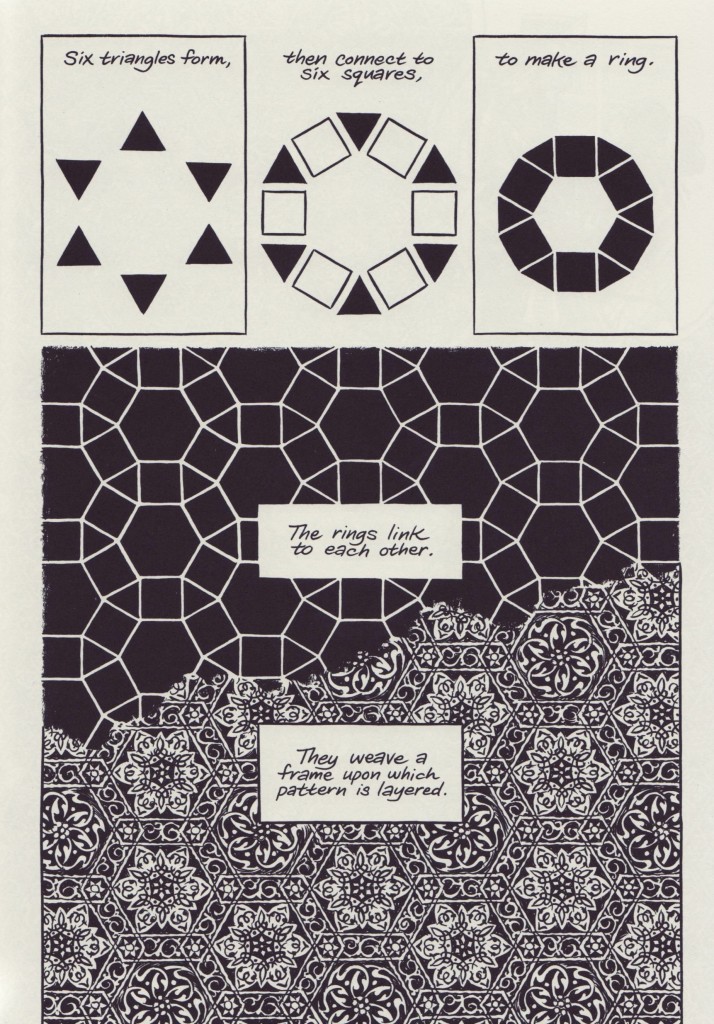

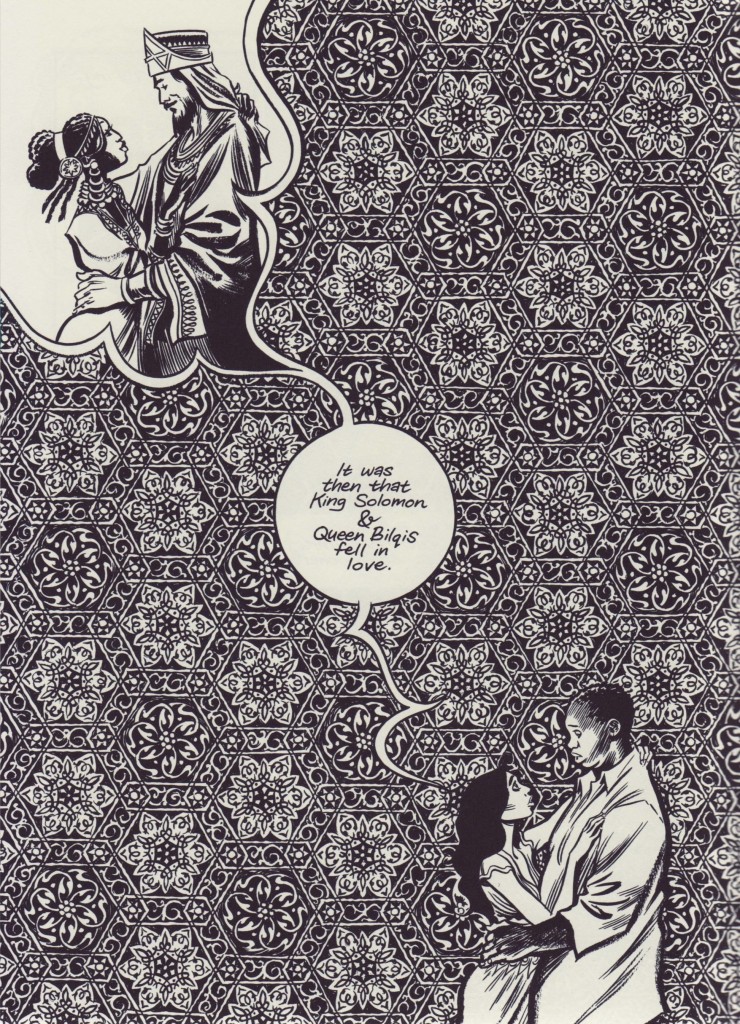

Along these lines, Thompson explores the geometric shapes of Islamic art to great success. The heavily detailed patterns he often uses in borders are the work of a talented, and slightly obsessive-compulsive, artist. The finely detailed explorations of Islamic patterns are a key part of what makes reading Habibi such a treat. As a reader I was often forced to pause in a page in praise of Thompson’s technical skill. While over-relying on this ornate style as shorthand for “Arab setting” made me raise a cautionary eyebrow beforehand, it is clear that Thompson is thoughtful in a way that escapes the pitfall. Here is a late in the text explanation of patterns that offers a glimpse into how thorough the cartoonist was in his research:

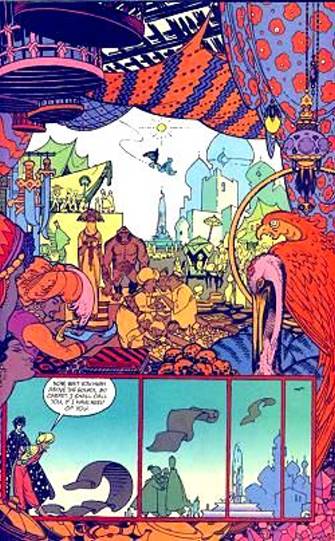

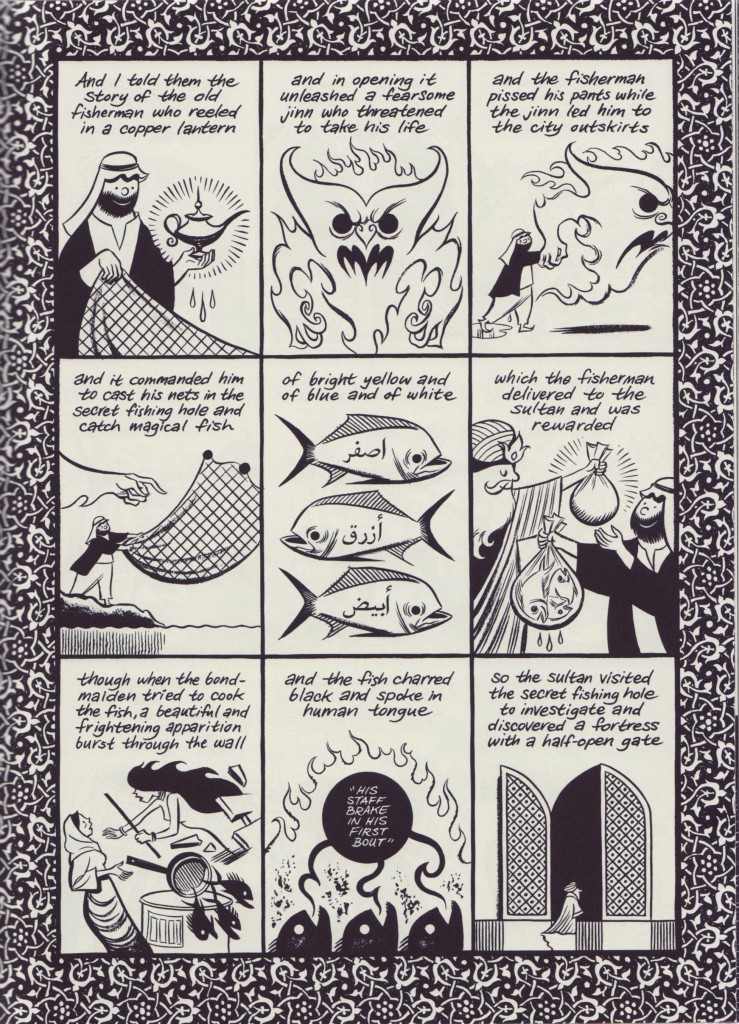

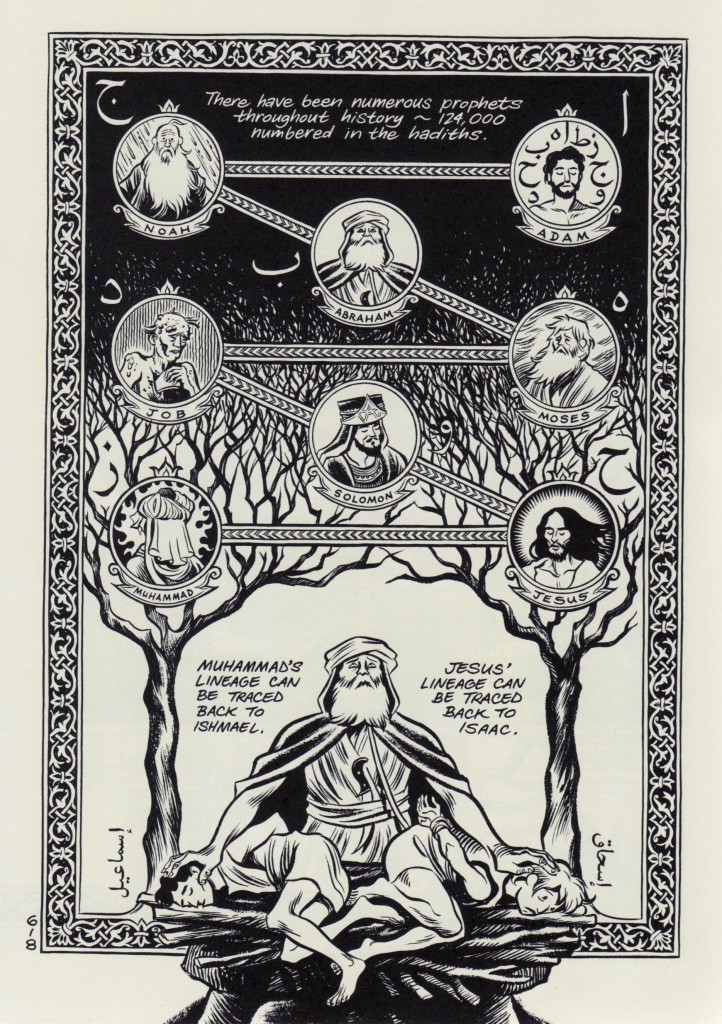

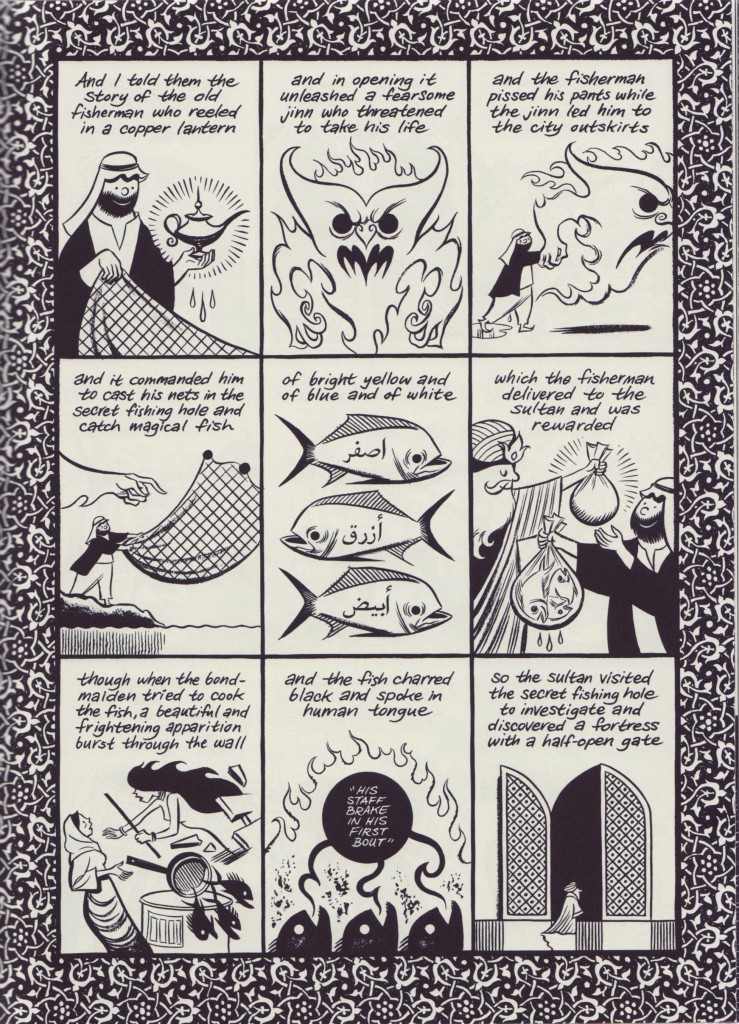

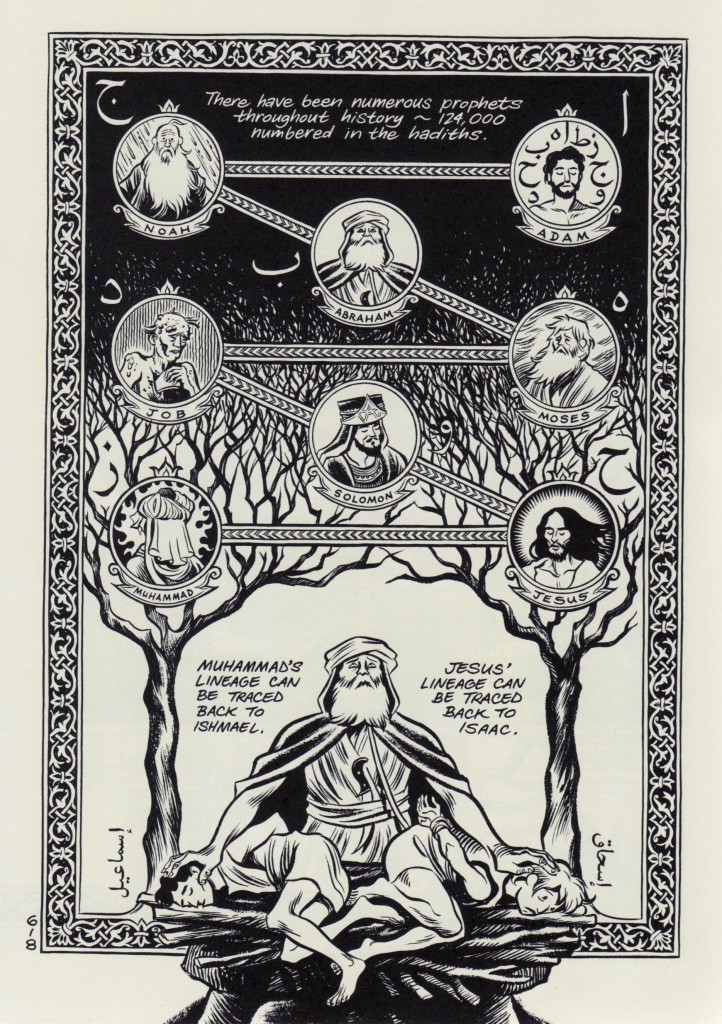

The second thematic triumph of Habibi is the manner which Thompson explores Islam. This clearly and heavily researched portion of the text contains the most exciting and memorable sections of Habibi by far. Thompson has mentioned the influence of Joe Sacco during the book making process and it is clear this is where Sacco’s research and report approach has influenced Thompson the most. Just as Sacco’s work lives in the footnotes of Gaza, here we get the product of Thompson diving deep into Islamic Hadith (the reported statements and actions of the Prophet Muhammad during his life), specific suras (chapters) of the Qur’an, and pre-Qur’anic mysticism. The threads he pulls out of his research are fascinating on their own right. His act of discovery is shared with the reader and it is clear he was excited to make it.

After reading the book it is evident that these are the sections Thompson refers to in his press when he talks about the book coming from a place of post-9/11 guilt. In the aftermath of September 11th, American Islamaphobia was predicated on understanding the attack by a few extremists as representative of an entire faith. Realizing this, Thompson uses Habibi to perform the due diligence of going into the Qur’an to reveal the large venn diagrams in between faiths. The question Thompson puts out there is: How can so many Christians and Jewish people be so against Islam when there are so many similarities between the faiths?

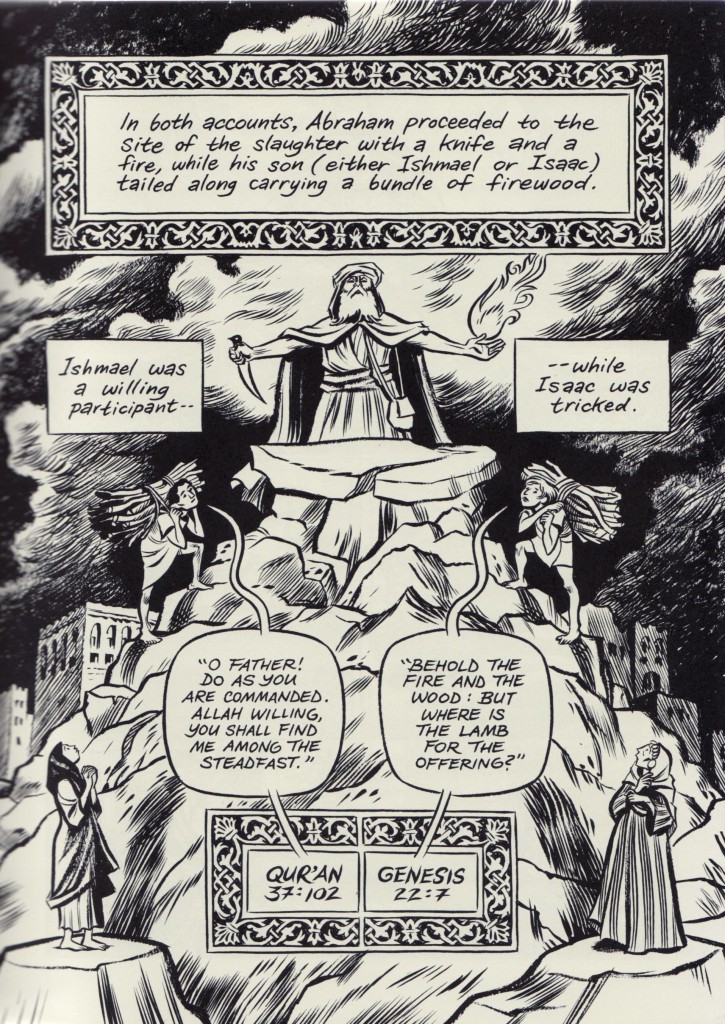

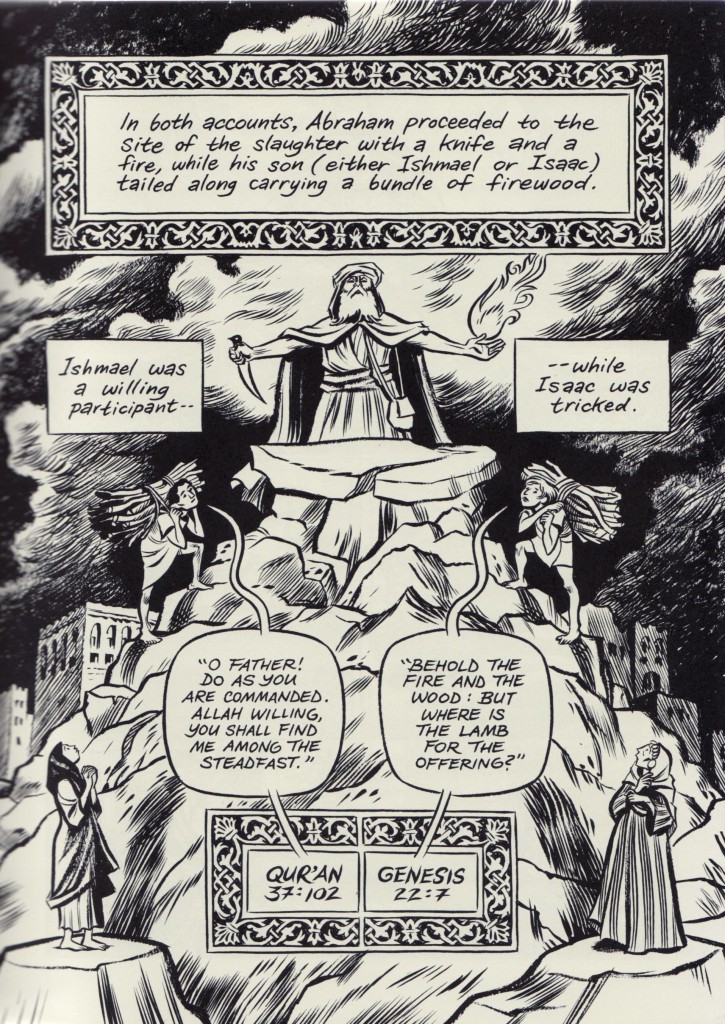

This exploration of the slight differences of the Abraham story between the Old Testament and the Qur’an — namely which son he takes to sacrifice — is one of the more successful uses of the Qur’an in Habibi. Thompson returns to this story of sacrifice multiple times in the narrative to increasing success, even when it simply used as a visual cue. By the end we get Thompson resolving the story by noting that in both versions what matters is that God spared the son, and from them the lineages of both faiths became deeply intertwined.

Thompson uses Habibi as a venue to argue that Islam and Christianity are not at odds with each other, but interconnected to one another. On this mark, Habibi is a well-done and original contribution to the canon of contemporary Western comics literature. I applaud Thompson for humanizing a religion that many have been quick to vilify, and for managing to do it in a non-preachy way. In fact, because he approaches Islam with a clear compassion and level-headedness, I suspect many readers let Thompson off the hook for the Orientalist elements of the text.

Which brings us to the bulk of the book: the love story between Dodola and Zam spanning multiple decades, set predominately in the land of Wanatolia. While this story is drawn with the same detail-attentive pen that Thompson uses at the service of calligraphy and geometric patterns, here it predominantly captures the vagueness of stereotypes. Thompson contributes to (instead of resisting) Orientalist discourse by overly sexualizing women, littering the text with an abundance of savage Arabs, and dually constructing the city of Wanatolia as modern and timeless.

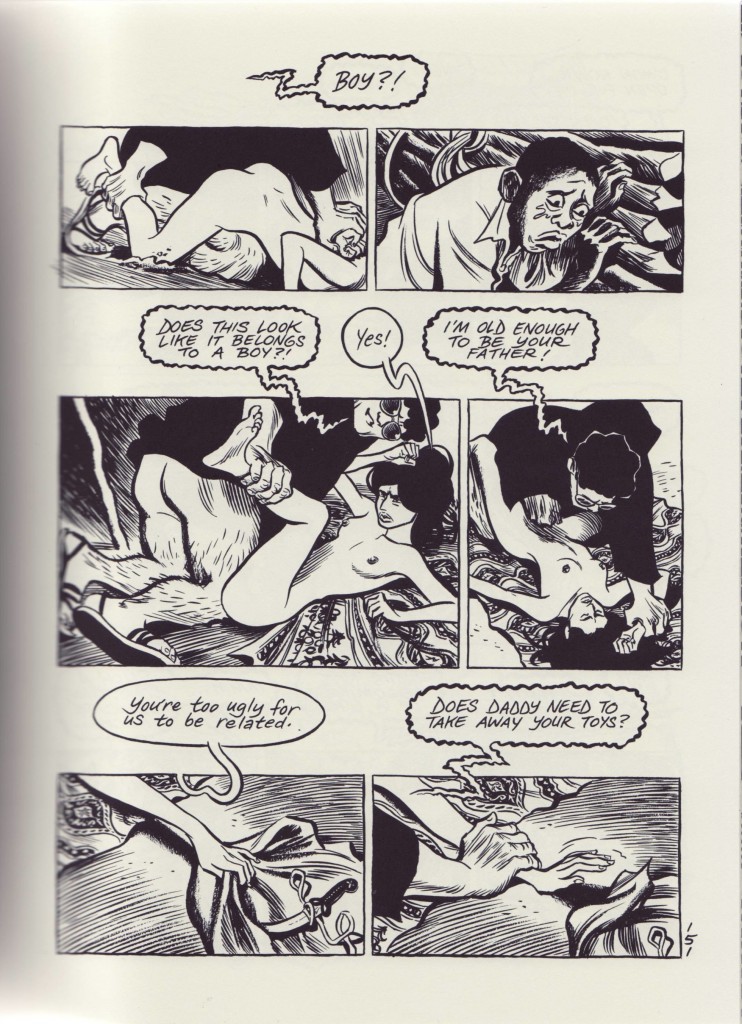

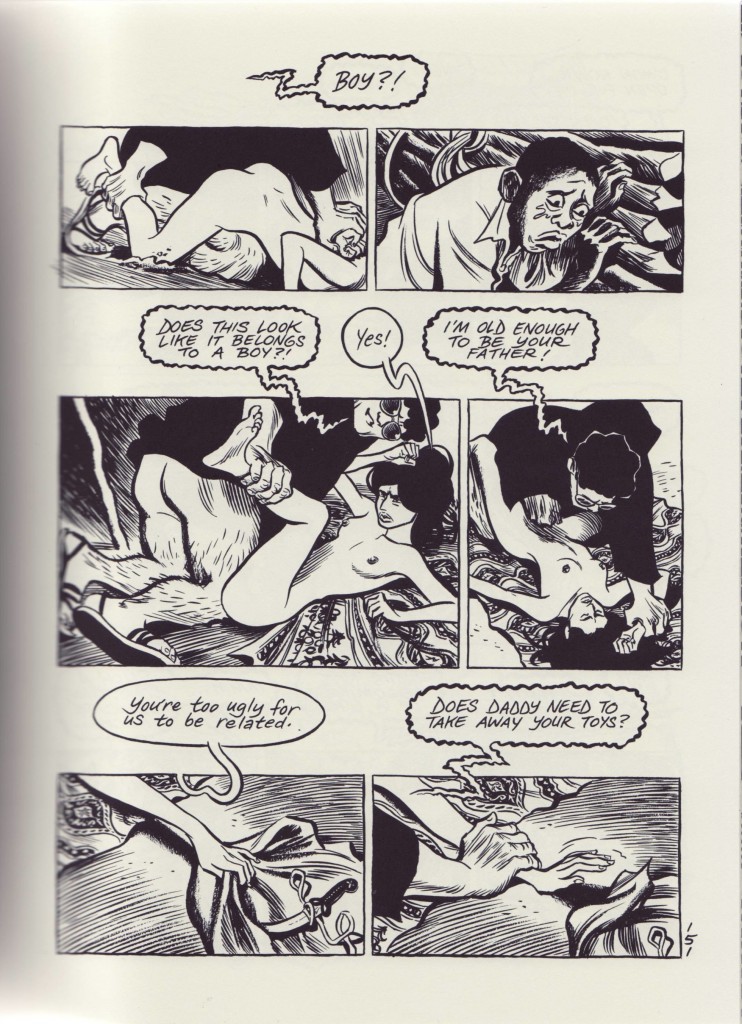

One of the biggest missteps that Habibi makes is relying heavily on unrequited sex as a main narrative thrust. In John Acocella’s critique of Stieg Larsson’s popular Girl With The Dragon Tattoo series from earlier this year, he notes that some charge Larsson of “having his feminism and eating it too” based on the blunt manner in which he uses rape as a plot device. I think a similar charge can be laid against Thompson, who uses the repeated rape (and sometimes consensual sex by circumstance) of Dodola as an emotional tool that never feels wholly earned.

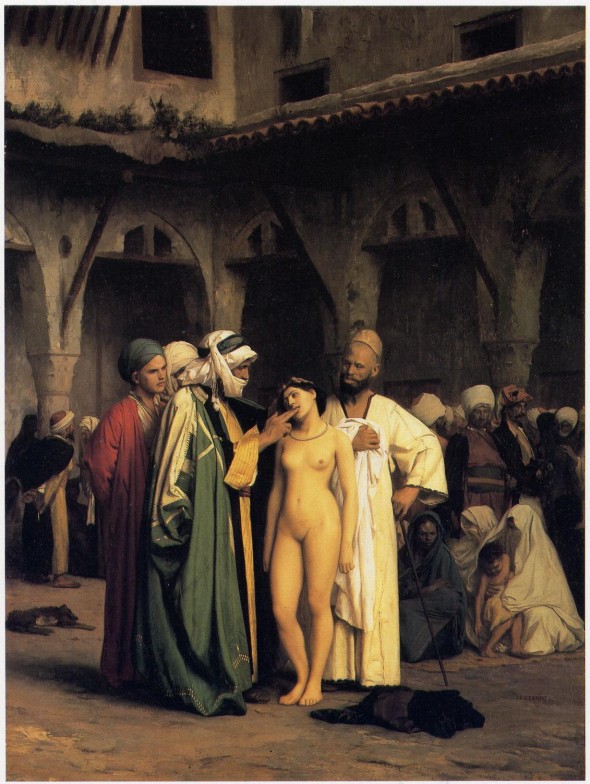

The rape of Dodola

What Thompson makes repeatedly explicit throughout Habibi is implicit in the classic Orientalist painting “The Slave Market” by Jean-Leon Gerome pictured earlier. In that painting, as with many more from the same era, the savagery of Orientals is imagined by European artists and portrayed for European audiences. What is reflected in these paintings is the White Man’s Burden: the felt need among those in the West to save Arab women from Arab men. By imitating the style of French Orientalist paintings as a vessel for his story, Thompson also transfers the message those paintings are loaded with. It is the same White Man’s Burden that drives readers to register Dodola as a damsel in distress (a position she inhabits for the majority of the book). She needs saving from the savage Arab men that over-populate the book.

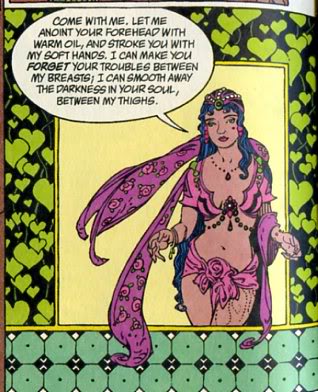

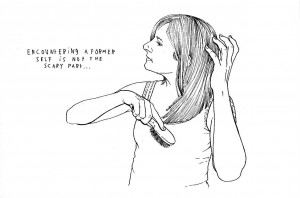

Furthermore, Thompson creates a world where Dodola’s chief asset is her sexed body. She sacrifices herself to men to feed Zam, gain a version of “freedom” with the Sultan, and save herself from jail. Thompson crafts a societal position for the main character of the book where she must always be exotic and sexualized. Proof of our empowered heroin:

The thing about this version of empowerment (as Acocella argues with The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo) is that while readers do feel solidarity with Dodola, they are also given a space to live out a version of their own sexual fantasies via the text. It’s hard to make the distinction between a character being overly sexualized as a necessity for a larger feminist narrative and the reality that the product of this narrative is a book with a nude exotic Arab woman in panel after panel.

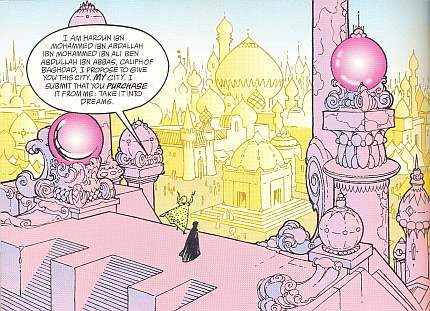

The question, then, is if Thompson so badly wanted to tell a story about what sex means in the context of love (familial to sexual), survival, and sacrifice, why did he choose this vessel? The answer I come to is that because this was the easy context. The artistic playground he chose of barbaric Arabs devoid of history but not savagery is a well-trod environment in Western literature, and one that is consistently reinforced in the pages of Habibi. In too many panels, Thompson conjures up familiar and lazy stereotypes of Arabs. From the greedy Sultan in his palace, to the Opium dazed harem, to the overly crowded streets of beggars, and the general status of women as property, Thompson layers the book with the hollow caricatures from other literature. These settings are easy to imagine because they have been passed down and recycled throughout much of Western media, so we immediately register these vague settings as natural:

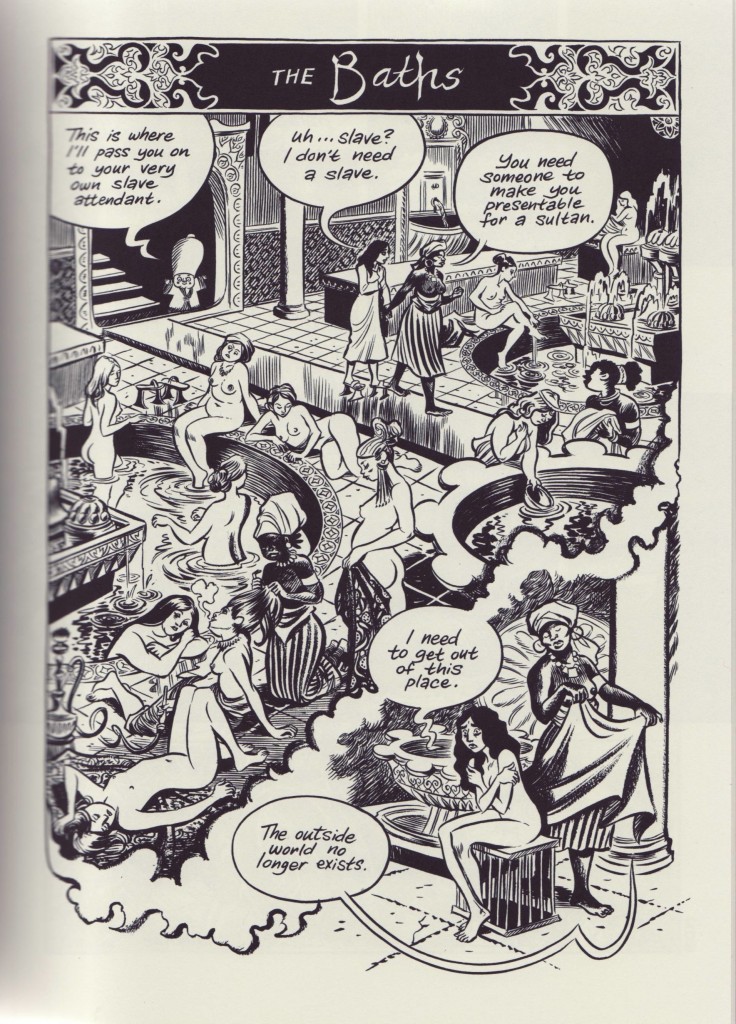

Nudity in Sultan’s Harem

Thompson constructs a version of the Orient that is filled with savage Arab men and sexualized Arab women, all at the service of penning a humanizing love story between slaves. The thing about humanizing, the way that Thompson does it here, is that while Dodola and Zam arrive as three-dimensional characters, they are made so by comparison to a cast of extremely dehumanized Arabs. While reading Habibi you can count the characters of depth on one hand with fingers to spare, but the amount of shallow stereotypes embodied in the supporting cast is staggering. The Sultan’s palace perhaps contains the most abundant examples of Thompson’s Orientalism. For the majority of the comic that takes place in the palace, the dialogue is so cliché-ridden that one could take out the words from the panels and the flow of the story would not be disrupted.

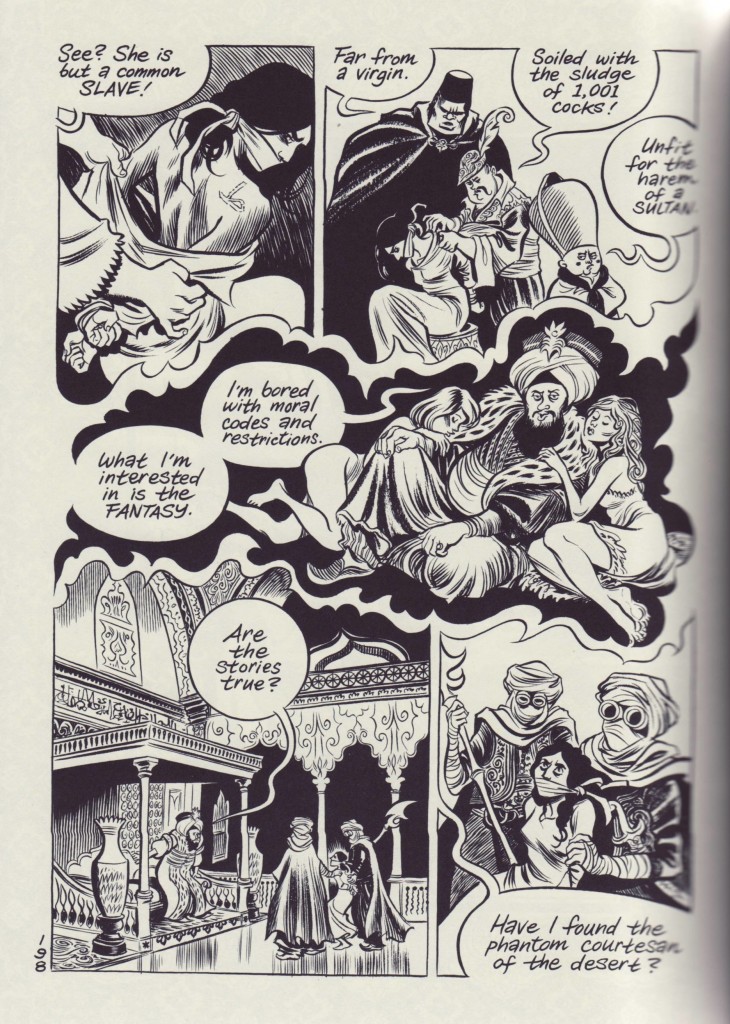

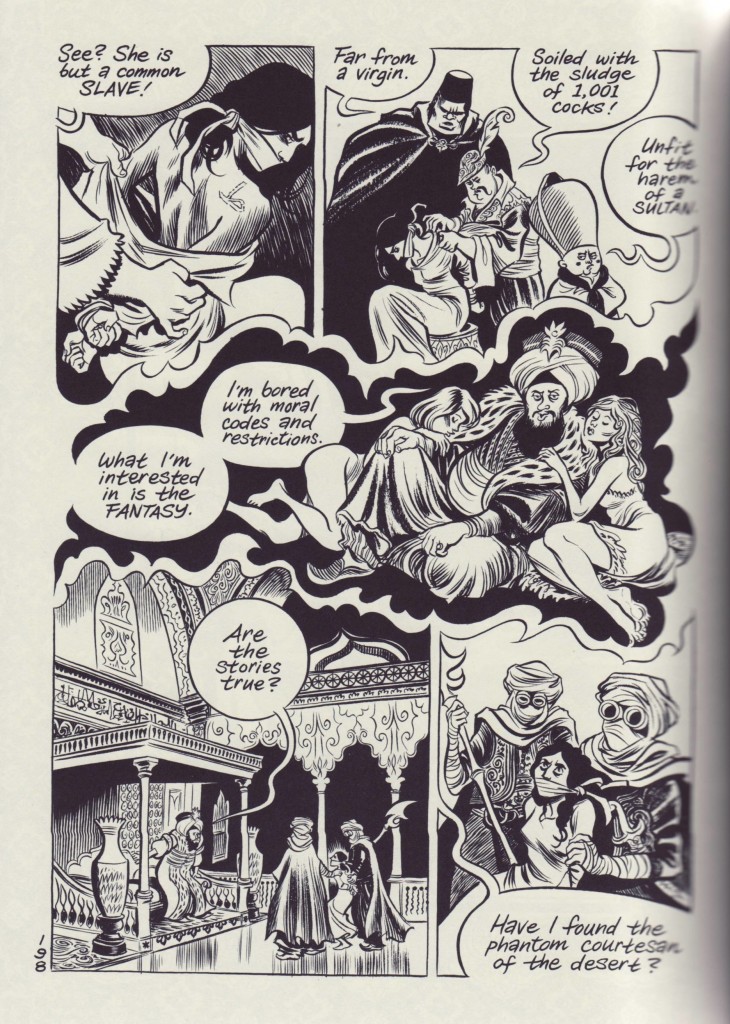

The Tusken Raiders present “the phantom courtesan of the desert”

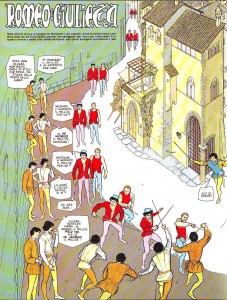

Thompson has often mentioned the influence of 1001 Arabian Nights on him when creating the setting for Habibi. It’s easy to see this connection through Dodola’s status in the palace, but I think Thompson may be understating the influence of a more contemporary take on one of those tales: Disney’s Aladdin. In the same way that this Gulf War children’s classic is a prime contemporary example of Orientalism in America, Habibi repeats many of the moves in a more highbrow setting. As Aladdin opens, a nameless desert merchant sets the tone for viewers in a song about the Arabian Nights we are entering:

Oh I come from a land, from a faraway place

Where the caravan camels roam

Where they cut off your ear

If they don’t like your face

It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home*

I thought of these lyrics repeatedly while reading through Habibi, as I could easily imagine the same desert merchant popping up in panels of Habibi to chime in: “It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home!” In Habibi, Dodola and Zam are struggling for a better life in a fixed system of backwardness. What is ultimately most frustrating about the brutality of Habibi‘s Arabs is it is a brutality that is never justified or made to face consequences: it just sits there as normalcy. Dodola being raped, the harsh way the city treats Zam when he is on his own, the Sultan’s ruthlessness, the caravan camels roaming: these are all just acceptable facets of Wanatolia being a faraway place. Like Arguba in Aladdin, Wanatolia is a made-up and timeless setting for love to spring in spite of Arabness.

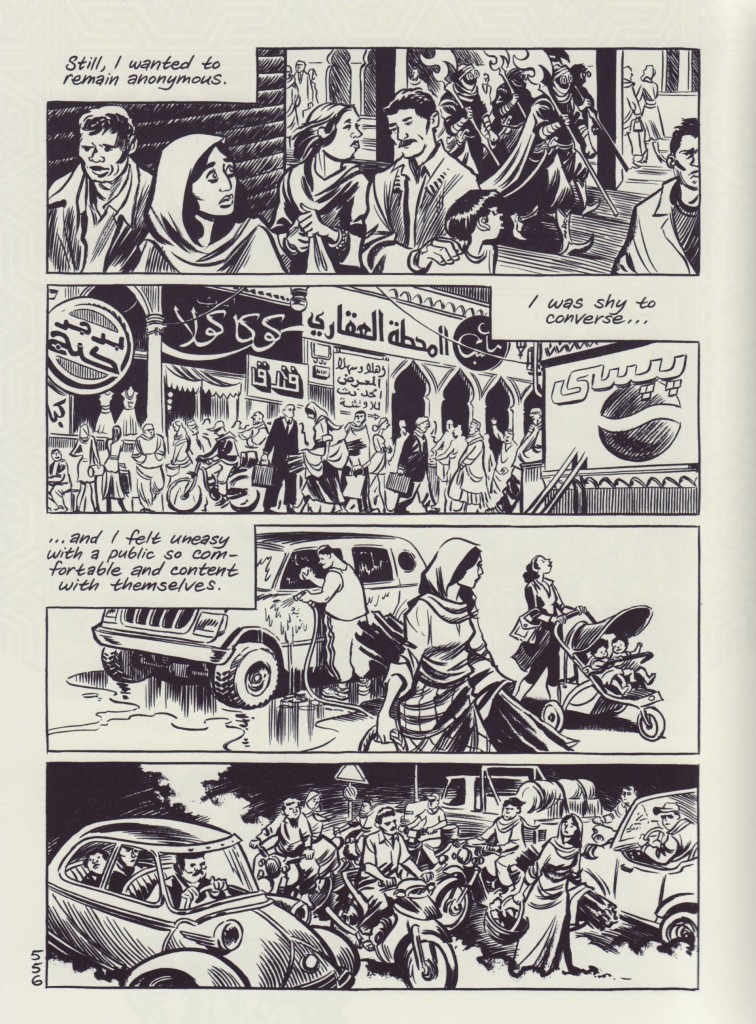

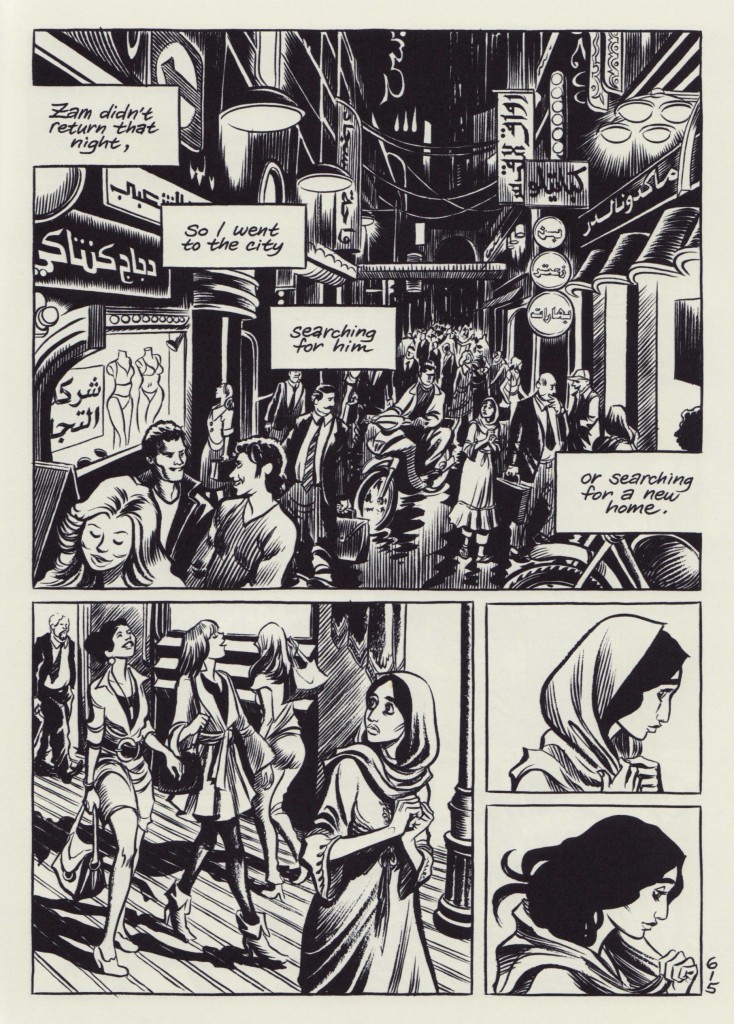

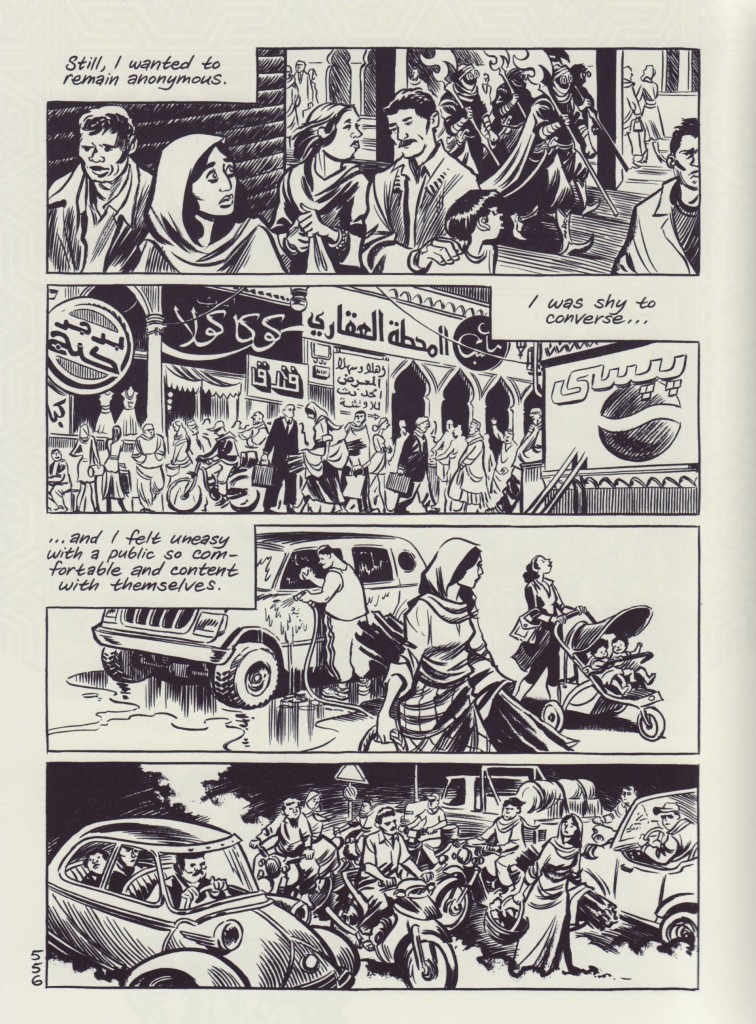

Wanatolia represents the heart of Habibi’s most problematic elements. In the sense that Habibi is a fairy tale (which Thompson has stated he was intending to create) it is understandable that the city is constructed as “timeless.” In other words, the majority of Dodola and Zam’s story isn’t tied to an analogous timeline. The problem arises when in the latter chapters of the book Thompson reveals that the same backward setting of Wanatolia (which houses the harem filled palace of the Sultan) dually houses a modern urban city. When Dodola and Zam return to Wanatolia after escaping the palace and recouping with a fisherman, we see the city in a completely new light: it is now a vibrant bustling city with billboards for Coca-Cola and Pepsi, SUVs, and free women pushing strollers.

The reveal means that readers now have to reconcile that the same city of Wanatolia houses in a small proximity a site of forced sexual slavery and a site of Western-style modernity; a city where an Arguba-like brutality lives in tandem with a KFC. Therefore, Thompson presents a version of modernization for Arabs that is fueled by backwardness. The entire events of the book are retroactively a modern reality in the wake of an urban Wanatolia.

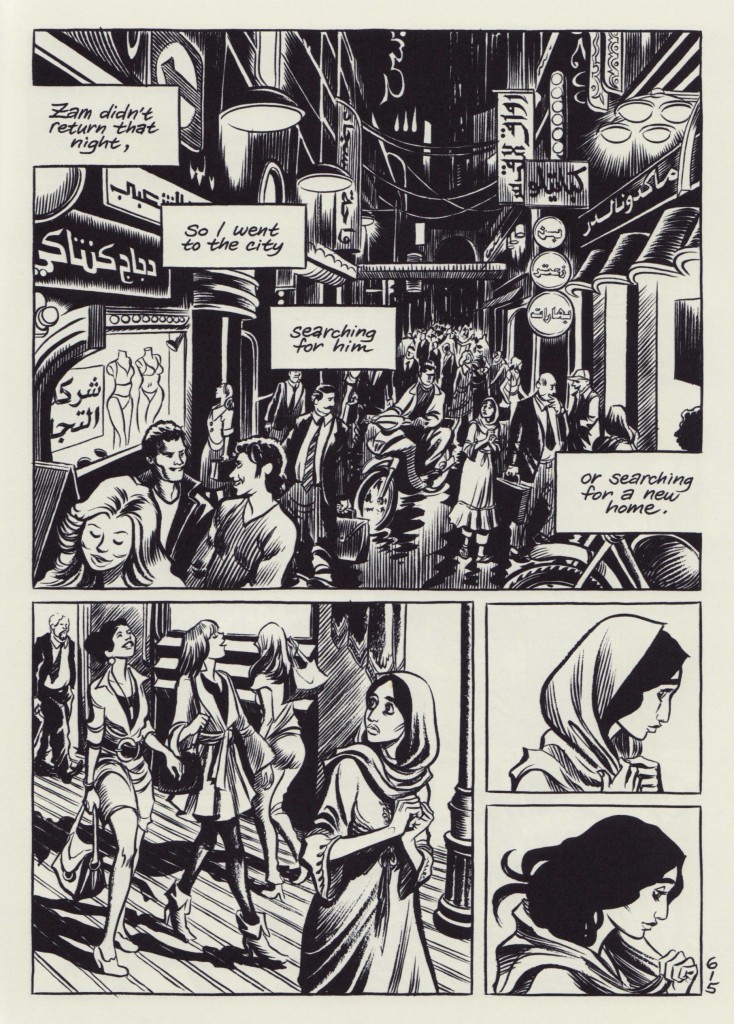

Dodola flirts with “being modern,” where “being modern” means taking off the hijab.

Wanatolia represents the poignant identity crisis at the heart of Habibi: it wants to be a fairytale and commentary on capitalism at the same time. The problem is that in sampling both genres so fluidly, Thompson breaks down the boundaries that keep the Oriental elements in the realm of make-believe. In other words, the way in which Wanatolia is portrayed as simultaneously savage and “modern” reinforces how readers conceive of the whole of the Middle East. Although Thompson is coming from a very different place, he is presenting the same logic here that stifles discourse in the United States on issues like the right to Palestinian statehood. If we are able to understand Arabs in a perpetual version of Arabian Nights, then we are able to deny them a seat at the table of “civilized discourse.”

Ultimately, when looking at Habibi we are left with the value of intention. Thompson has argued rather convincingly in recent talks that the book is knowingly Orientalist and he wanted to engage with these stereotypes to simply play within the genre. As he claims in the quote that leads this review, he intended to use Orientalism as a genre to tell a tale about Arabs the same way that stories in the genre of Cowboys and Indians are both fun and inaccurate. The problem in making something knowingly racist is that the final product can still be read as racist.

I know that Craig Thompson is a great guy who would probably win an award for thoughtfulness if such an award existed, but the issue remains that Habibi reproduces many of the Orientalist stereotypes already abundant in Western literature and popular culture. Although Thompson set out to play with these stereotypes, he never does a good enough job distinguishing what separates play from his own belief.

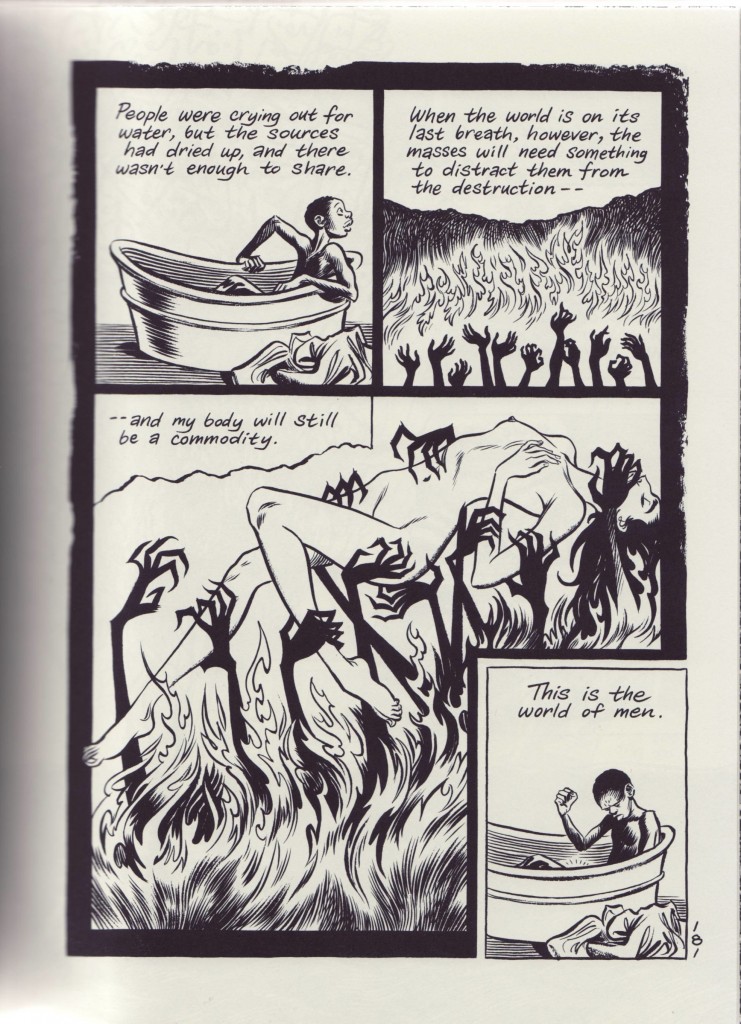

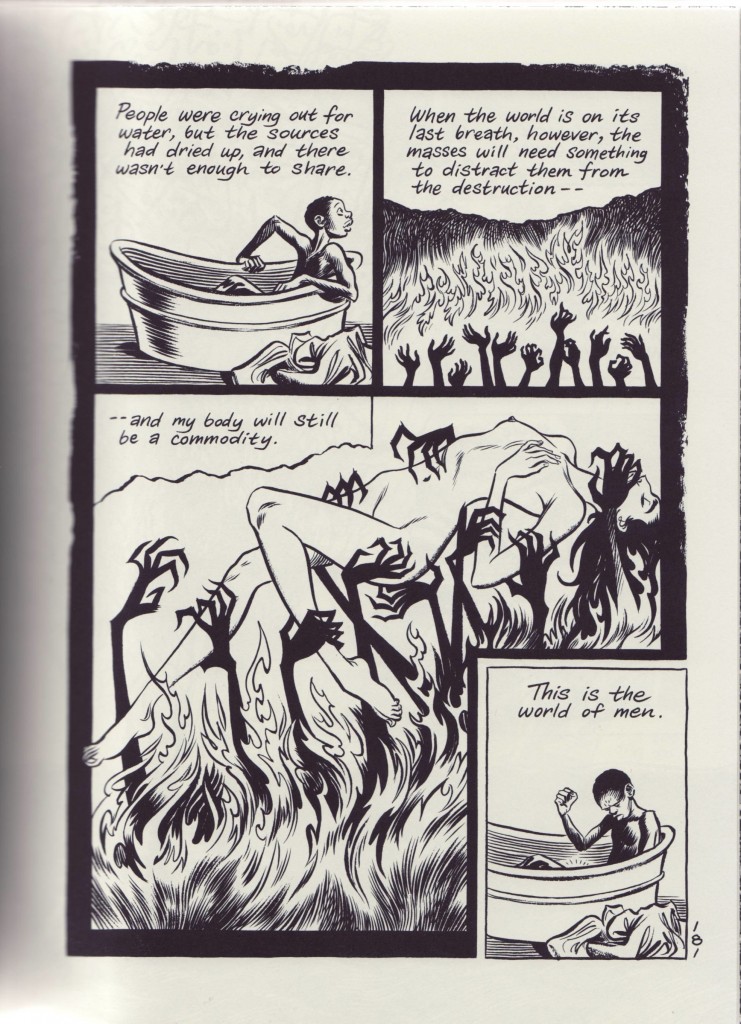

Habibi is an imperfect attempt to humanize Arabs for an American audience. There are definitely large technical and thematic triumphs to note, some of which I’ve mentioned here (from calligraphy to Qur’an) and others of which I didn’t get to (particularly the role of water/environmental concerns in the narrative). On an aesthetic level, Habibi is a wonderful experience that I recommend to anyone with spare time and the ability to lift heavy objects. Thompson is one of the most talented comic artists and writers working today, and that he took seven years working on Habibi is evident in the ink on display throughout the book. Yet, between the eroticized women, the savage men, and the presentation of these elements as constituents of Arab modernity, it is unfortunate Thompson’s skills are being used at the service of a mostly Orientalist narrative.

* The lyric “they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face” was removed in subsequent versions of Aladdin due to a complaint by the Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC). I recommend reading the ADC’s explanation of the situation.

_____________

Update by Noah: Nadim’s thoughts have inspired an impromptu roundtable on Orientalism. which can be read here as it develops.