While I haven’t yet met anybody whose favorite Tintin adventure is The Crab with the Golden Claws (Crab), it is certainly an important text in the scale of Hergé’s overall story about the boy reporter.* For one, Crab is the album in which Tintin meets, is repeatedly almost killed by, and ultimately befriends the perpetually drunk Captain Haddock. As such the album will presumably serve as the first act of Steven Spielberg’s 3-D monster The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Anglophiles. Penned in 1941, Crab is also notable for being the first story Hergé published during Belgium’s occupation by Nazi Germany in the newspaper Le Soir. But what I find most intriguing about Crab (besides its relatively recent Simpsons cameo) is its long and curious history of edits, some of which I will explore today.

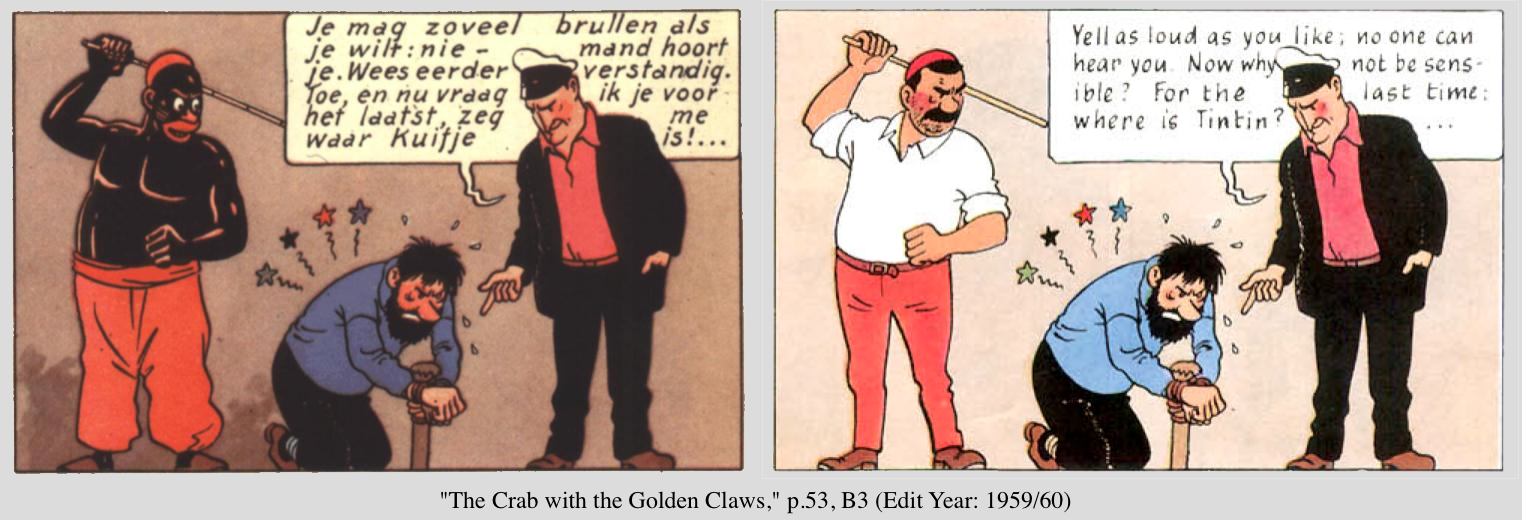

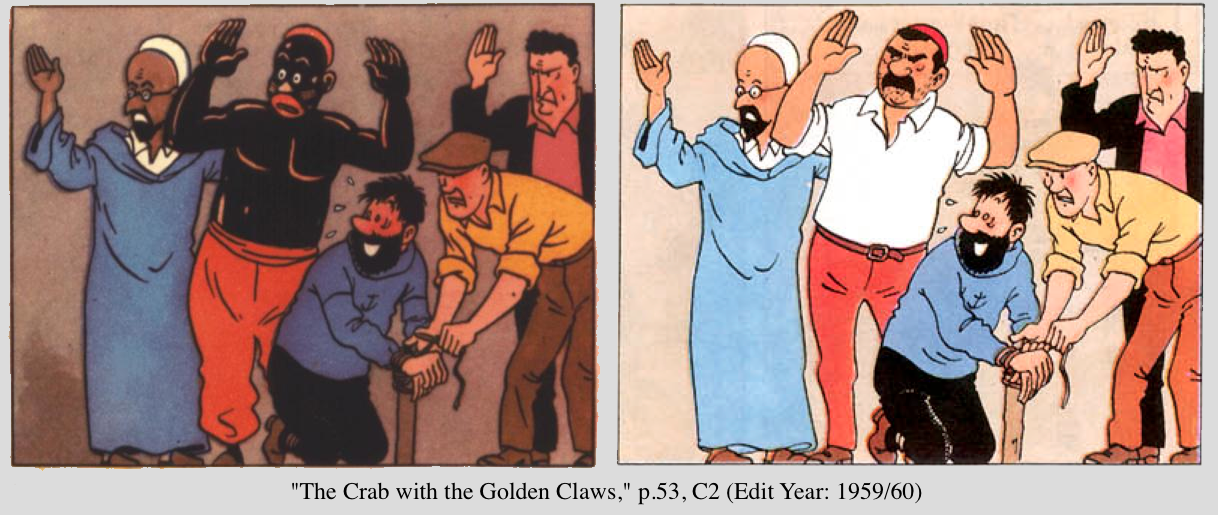

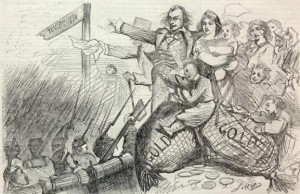

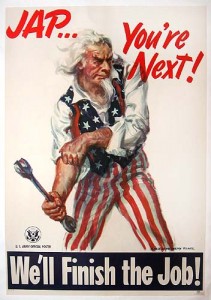

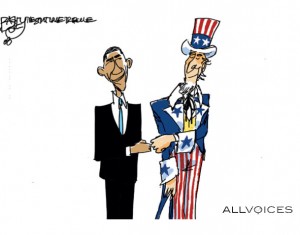

Deckhand “Jumbo” becomes markedly whiter.

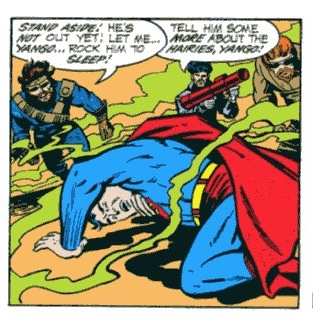

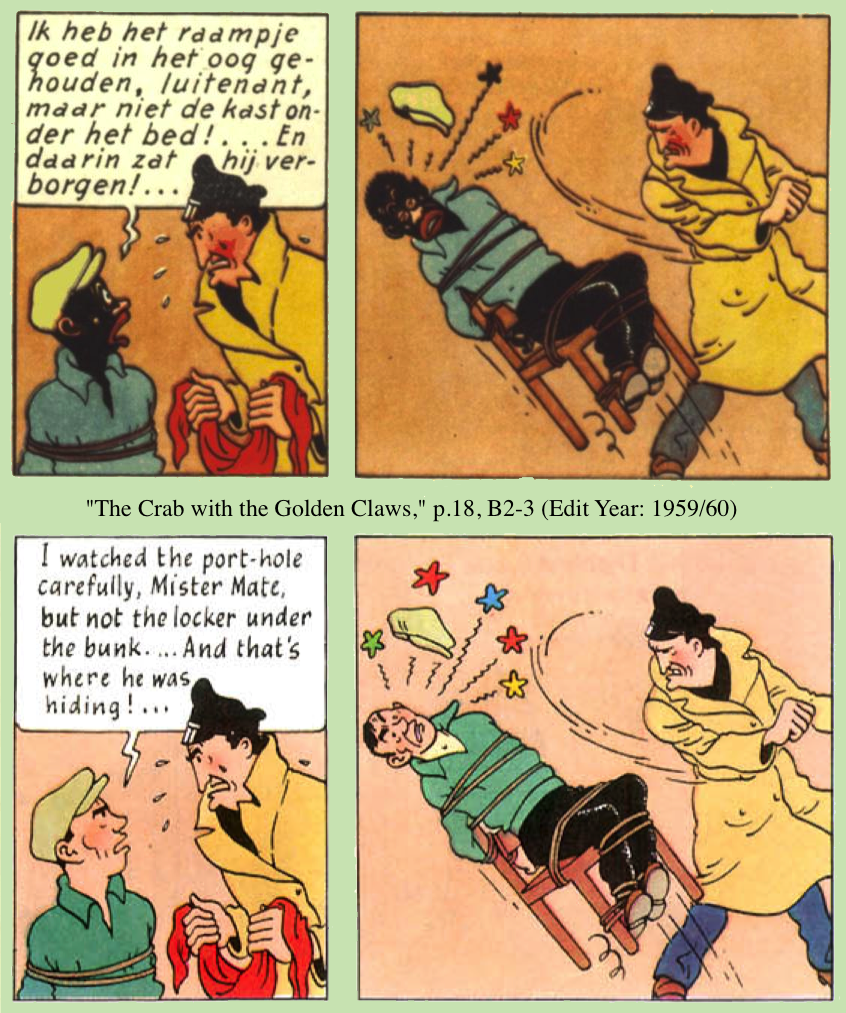

Deckhand “Jumbo” becomes markedly whiter.Before the translations [into American English] began in earnest, Hergé agreed to redraw several panels for The Crab with the Golden Claws depicting black characters. The US censors didn’t approve of mixing races in children’s books, so the artist created new frames, replacing black deckhand Jumbo with another character, possibly of Puerto-Rican origin. Elsewhere, a black character shown whipping Captain Haddock was replaced by someone of North African appearance.

Put simply, Hergé replaced his black characters with a possible “Puerto-Rican” in one instance (illustrated above) and an Arab in the other. In his wonderful series Tintin in Otherland, Alex Buchet has addressed Hergé’s overall problem with representing “others” and touches on the creators often sardonic response to charges of racism. A typical defense from Hergé in his latter days reads like this quote from a 1975 interview: “In a nutshell, Soviets and Congo were ‘sins of my youth.’ That’s not to say that I disown them, but in the end, if I had to do them again, I would do everything differently for sure, and then all my sins would be forgiven!” (Hergé in His Own Words, 25).

Indeed, in response to these very edits that Golden Press requested him to make for American editions of Crab, Hergé sarcastically stated: “Everyone knows that there are no blacks in America” (Source). While I can spend (and others already have spent) hours parsing Hergé’s half-hearted verbal defense of his “sins of youth,” I rather call to question specifically why he changed the mysterious and speechless henchman featured heavily in the latter pages of Crab from African to Arab.

Privately, I’ve come to refer to this textual change as “The Case of the Arab Henchman” and it is a case I often refer to while trying to locate Hergé’s view on non-white people. Considering Tintin was Hergé’s job for the majority of his life, often the best point of entry into the man’s personal beliefs are scattered throughout the pages of the comics themselves. Not to overstate this, but having read both versions of Crab — one with the African Henchman and one with Arab Henchman — it is remarkable how similarly they flow. Put differently, even though he changes the race of a character featured in upwards of 12 panels, nothing feels different narrative-wise. Which forces me to ask why?

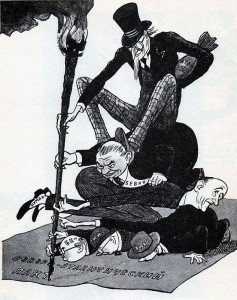

The question Hergé had to answer (probably implicitly) when requested to edit out the nameless black henchman he drew in 1921 for someone new in 1959 was “who can I change this with so that the narrative will maintain its plausibility, but without offending anyone’s sensibilities?” The answer came in the new acceptable stereotype of Arab lackey, which is precisely harmful as most stereotypes are because of its vagueness and interchangeability. To be clear, I’m not saying that this new henchman was a worse stereotype than the old one, or that the original crude depiction shouldn’t have been changed, but I am questioning how this new stereotype was acceptable in a way that the old one was no longer. And while I’m not pointing out anything you can’t find worded better in Said’s Orientalism, I still find the need to point it out pressing, especially considering the Arab henchman was re-presented without question to an Arab audience upon Tintin’s translation into Arabic:

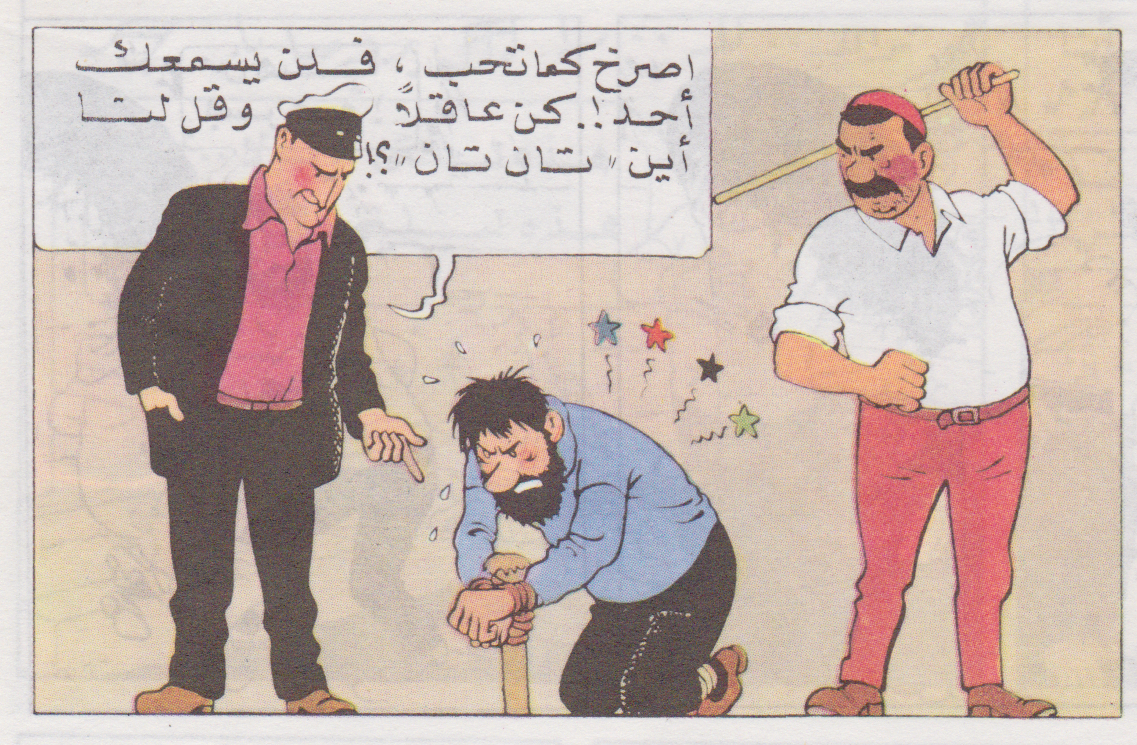

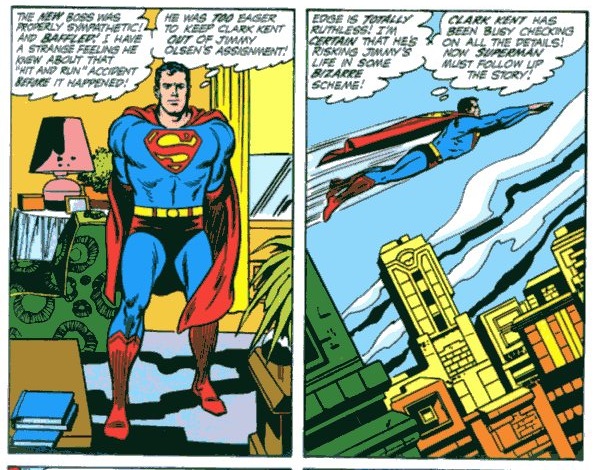

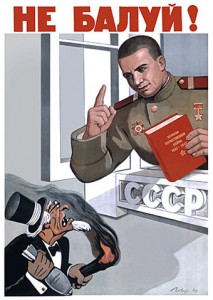

In the 1970s, Tintin was translated (legally) into Arabic by long-running Egyptian publisher Daar el Maaref and thereafter made available in the standard album format for a receptive Arab audience.** During the translation/transition into Arabic, it is important to note a few things were adjusted to fit better culturally among the new readership. However, while the censors of Golden Press were enough to make Hergé change a henchman from African to Arab, there clearly wasn’t enough sensibilities being upset to make the henchman change yet again. The Arab Henchman was accepted, and future generations of Arab children would internalize the mustachioed man whipping their beloved Captain Haddock, hoping for Tintin to interrupt with his gun in the name of justice. Equally intriguing as I’ve reread Crab is what did get changed as Tintin learned to speak Arabic:

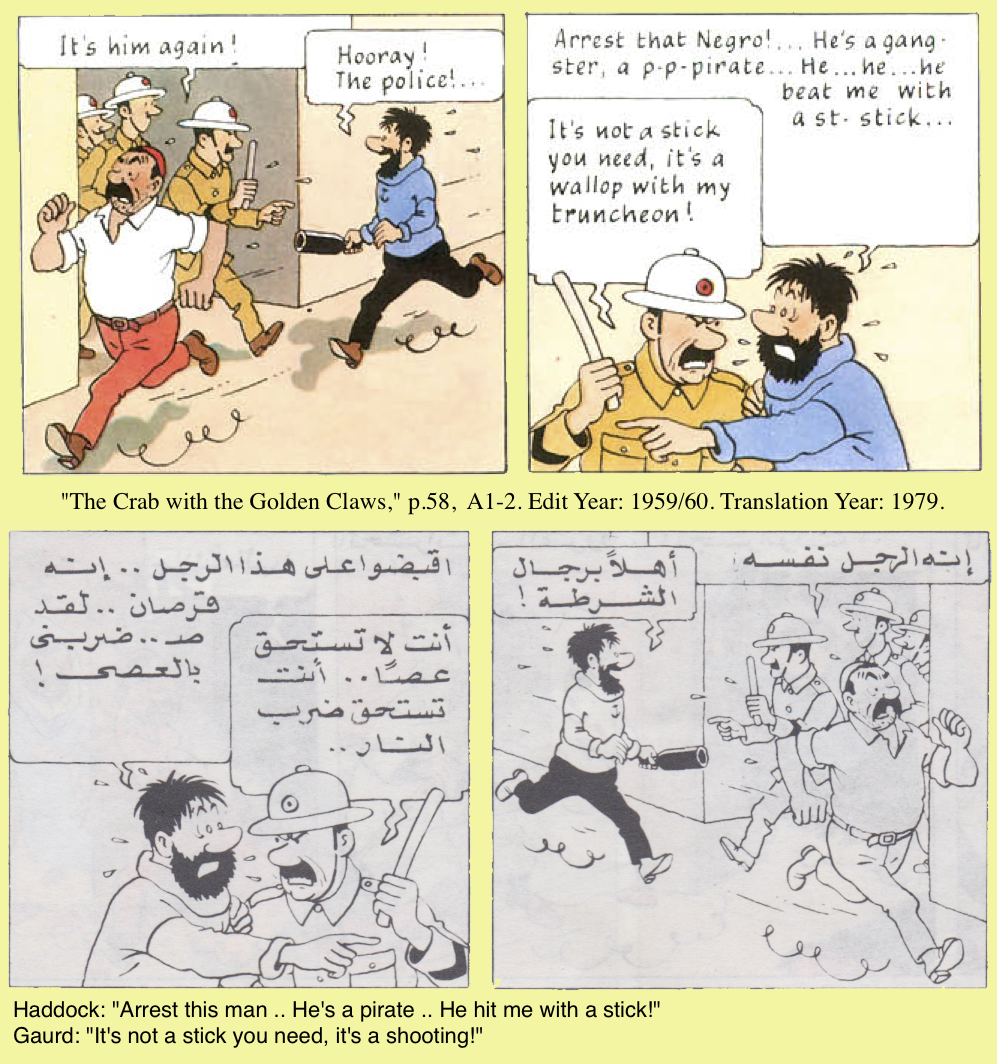

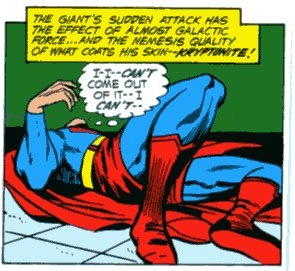

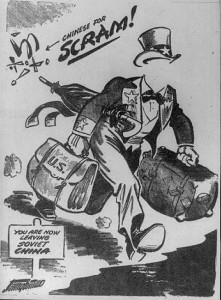

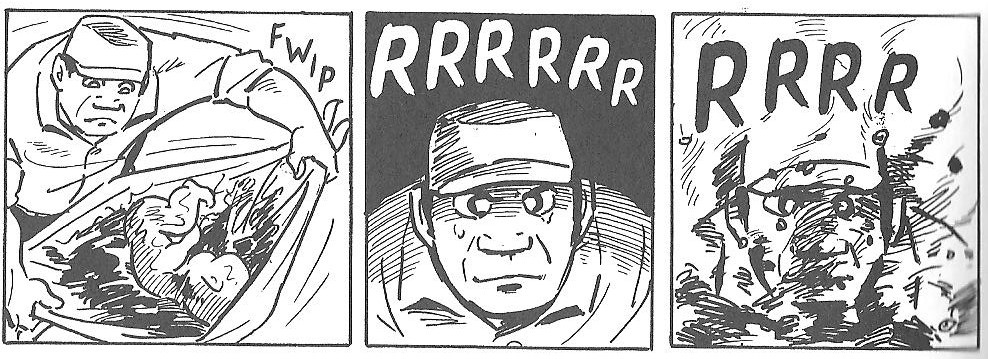

I’ll give you a second to re-read the dialogue from the top panels. As it is available on bookshelves today (English readers, check your collection), Captain Haddock calls the Arab Henchman a “Negro.” I was curious to see how this bad bit of editing was translated into Arabic, only to find that it wasn’t translated at all. As you can see (from right to left because that’s how Arabic works), Haddock tells the police to arrest the “man,” not the “Negro.” Therefore it appears the translator/s were aware there was a weird edit in the pages, and their solution (with Hergé’s old age no doubt a factor) was to accept the art and change the words. Elsewhere, the Arabic version of Crab contains another bit of tidy work:

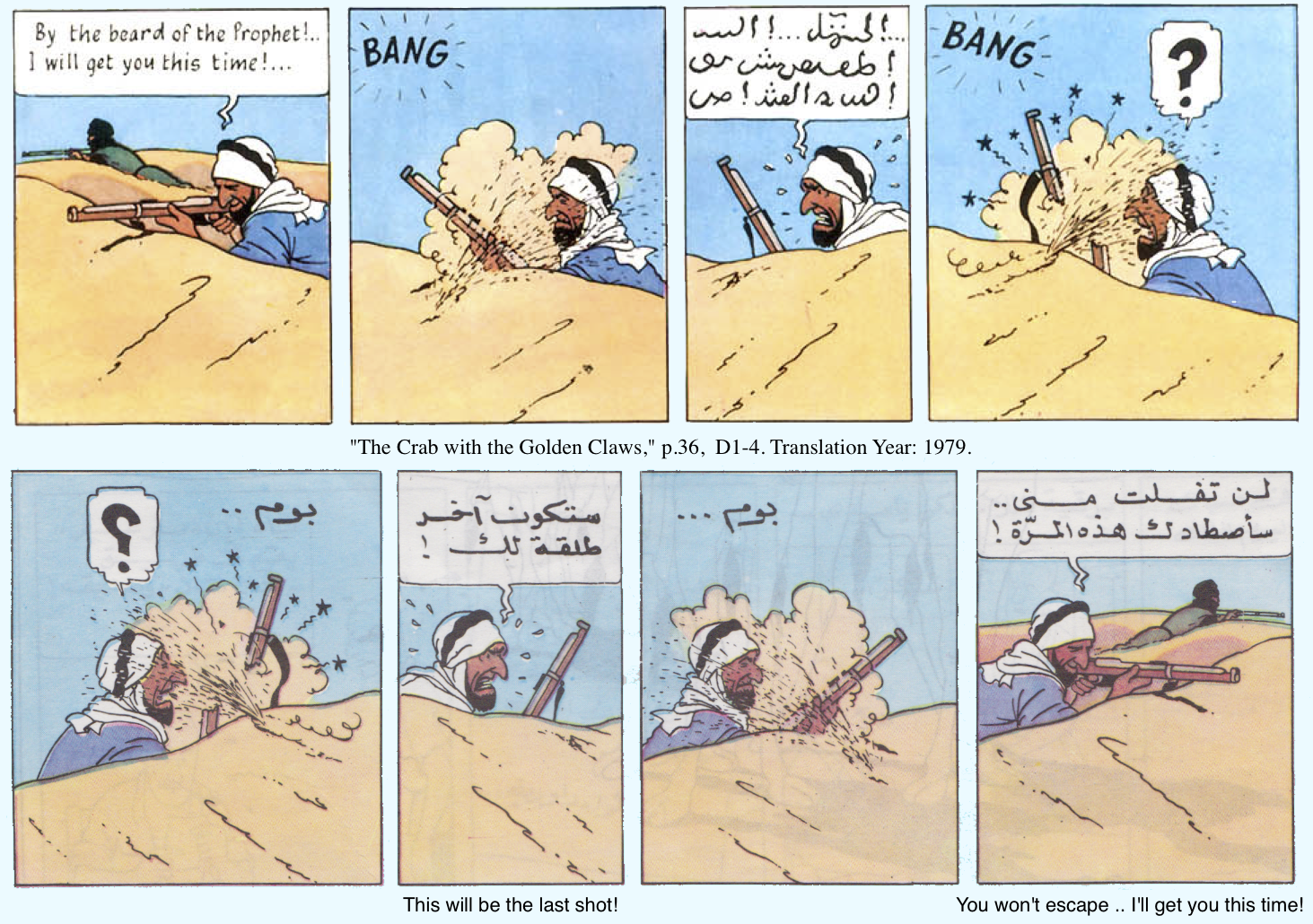

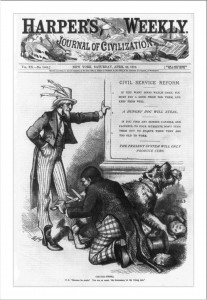

Above in the desert shoot off between Haddock and another unnamed Arab, two distinctive edits are made in the Arabic translation. First, instead of saying “By the beard of the Prophet!” as Hergé supposedly imagined an Arab in combat might, the reference to Prophet Mohamed is replaced with “You won’t escape.” Second, instead of keeping the nonsensical squiggly lines that Hergé used to represent a phrase in Arabic, the translator put actual Arabic text (“This will be the last shot!”). I find these two subtle edits to be a positive element of the Arabic editions of Crab. Instead of accepting Hergé’s stereotyped language decisions for an Arab character (prophet-referencing, fury squiggles) the translator took it upon herself to create language based slightly closer on reality. While these edits don’t produce the same (arguably) culturally-balanced product as Hergé’s famous collaboration with Zhang Chongren in The Blue Lotus, they do help the work take a small step away from being based solely on Hergé’s mind-forged manacles. The translators clearly made a conscious effort in the small wiggle room they had access to, but when faced with a speechless character like “The Arab Henchman,” it seems an eraser is the only way to effectively curb a misguided stereotype.

—

*To put this in context, I even met someone who named Soviets as their favorite album.

** I should note that Tintin adventures have been available in colloquial Arabic for consumers as far back as 1956 in the pages of Cairo-based Samir Magazine. Although not legal, these translations meant readers were exposed to Tintin well before Daar Al Maaref editions were available.