This first appeared on Splice Today.

_______________

Romance was her suicidal substitute for action, fantasy her suicidal substitute for a real world, a wide world. And intercourse was her suicidal substitute for freedom.

— Andrea Dworkin, Intercourse, 1987

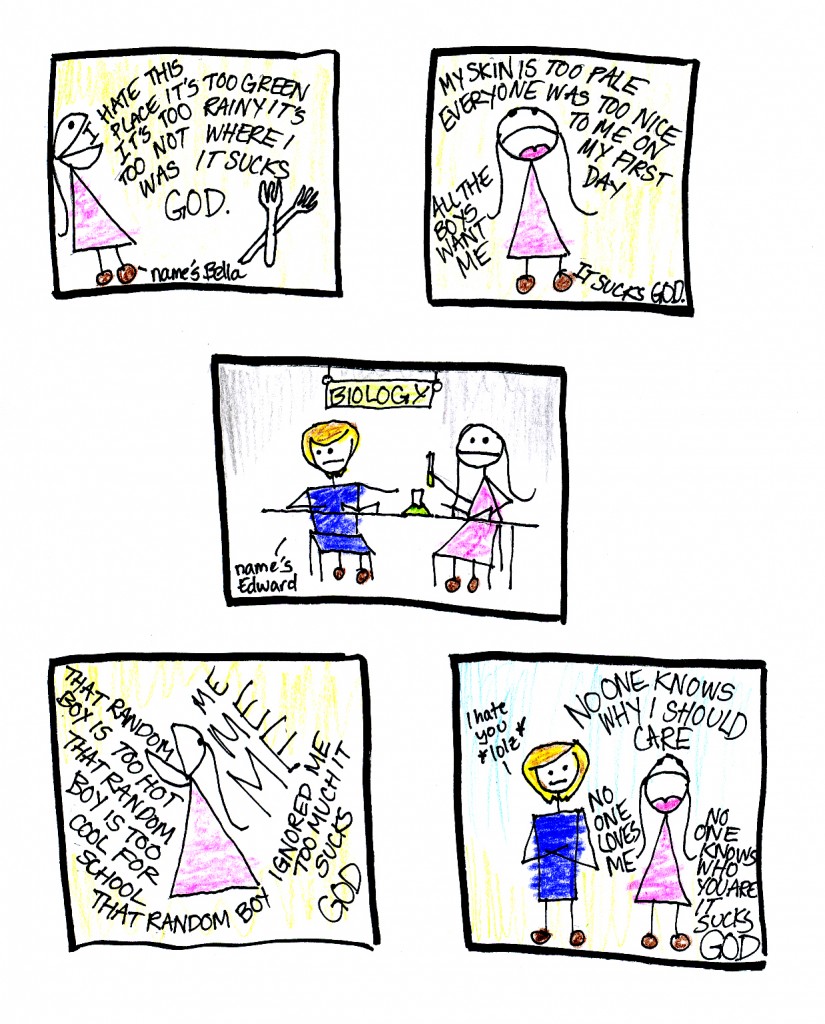

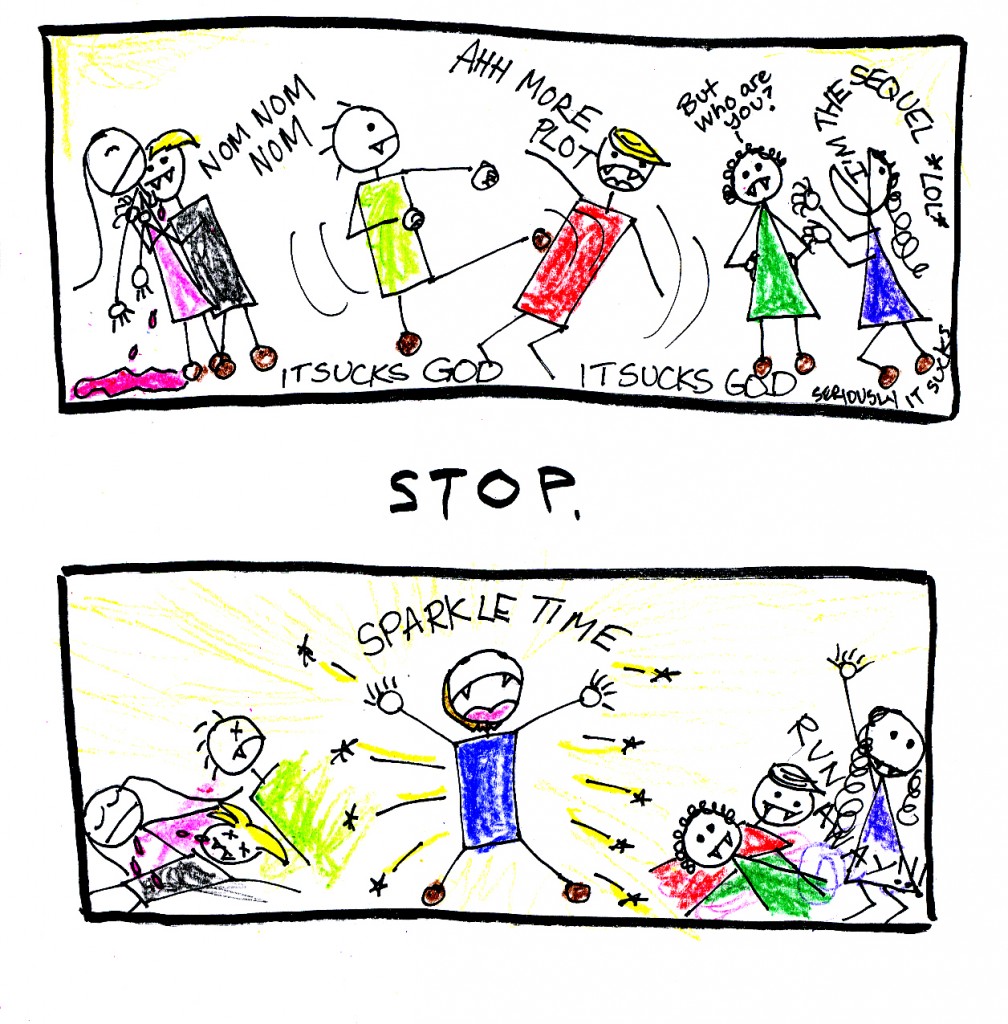

In the quote above, radical feminist Andrea Dworkin is speaking about Madame Bovary. But she could just as easily be referring to Bella Swan, the heroine of Stephenie Meyer’s preposterously successful tween vampire book and movie series Twilight. In Twilight, Bella does substitute romance for action, abandoning her future plans, her academic interests, her family, her personality,and her life for her vampire lover Edward Cullen. She substitutes fantasy for reality in a manner which is literally suicidal, choosing to die and enter the twilit unageing faery world of the undead rather than grow into the responsibility and autonomy of adulthood. And she substitutes intercourse for freedom, believing that being “bitten” will grant her self-determination and happiness, when, in fact, it will simply kill her.

In the quote above, radical feminist Andrea Dworkin is speaking about Madame Bovary. But she could just as easily be referring to Bella Swan, the heroine of Stephenie Meyer’s preposterously successful tween vampire book and movie series Twilight. In Twilight, Bella does substitute romance for action, abandoning her future plans, her academic interests, her family, her personality,and her life for her vampire lover Edward Cullen. She substitutes fantasy for reality in a manner which is literally suicidal, choosing to die and enter the twilit unageing faery world of the undead rather than grow into the responsibility and autonomy of adulthood. And she substitutes intercourse for freedom, believing that being “bitten” will grant her self-determination and happiness, when, in fact, it will simply kill her.

In short, the millions of tweens trooping in lockstep to the Cineplex to see the latest Twilight Saga installment might as well be trekking over Dworkin’s corpse. It’s a wonder she doesn’t just rise right out of the ground, fangs bared, spitting blood, and personally castrate both Robert Pattison and Taylor Lautner with a rusty cleaver out of pure spite.

I don’t really have much doubt that Dworkin would really and truly have hated Twilight. She hated most things; it was part of her mean-spirited second-wave charm. At the same time…there are aspects of Twilight that resonate in odd harmony with Dworkin’s particular feminist convictions.

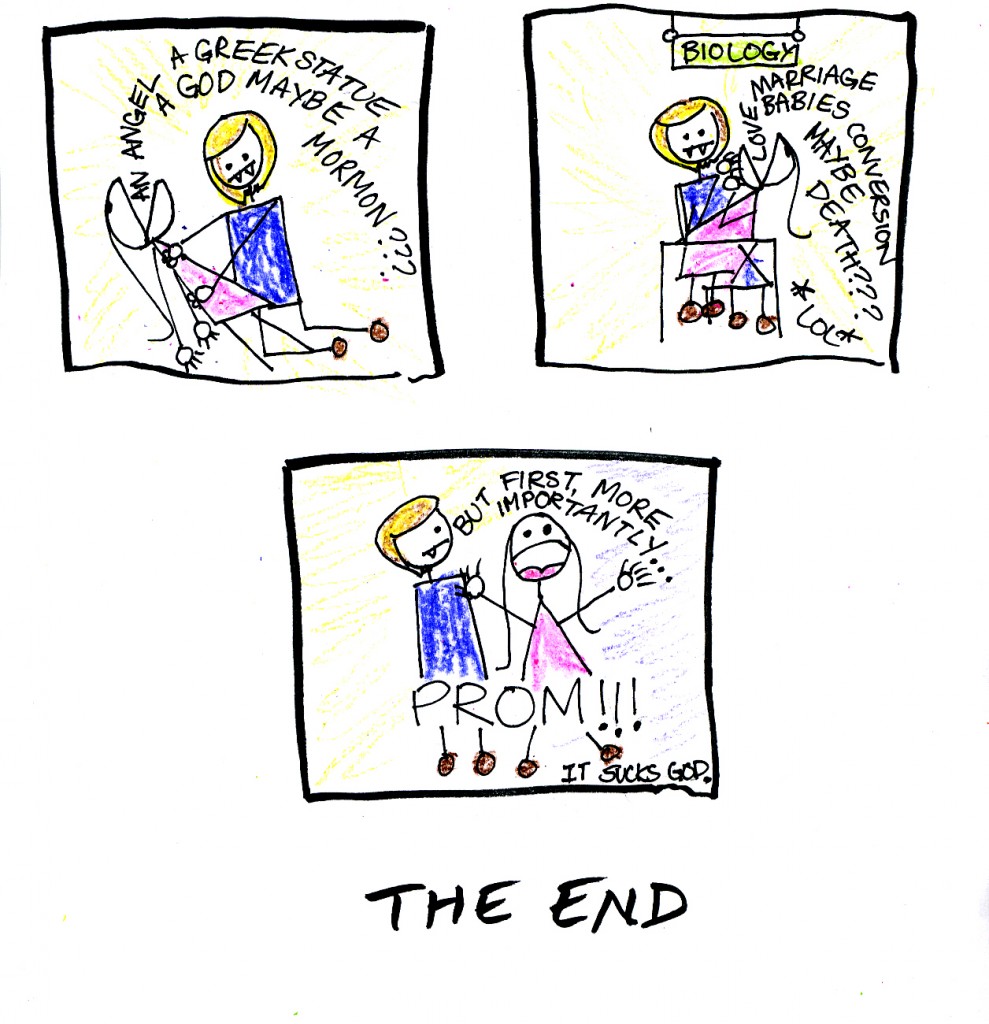

The most obvious of these is virginity. Stephenie Meyer is a Mormon, and her novels are obsessed with self-control in general and chastity in particular. The chastity is both literal and metaphorical; Edward won’t sleep with Bela before marriage both because he doesn’t want to damage her immortal soul and because he’s afraid of hurting her physically— he won’t bite her and turn her into a vampire for analogous reasons.

On the one hand, this virginity seems to be more about Edward’s struggle; a typical conservative vision in which female safety is placed in the hands of male renunciation and chivalry. But there’s also a sense in which virginity is not about Edward at all, but is instead Bella’s gift. Edward has a special vampire superpower, and can read minds — but for some reason he can’t read Bella’s. Over the course of the series, Bella proves immune to the mind manipulation powers of various other vampires; she is “safe in her own mind” as the books put it.

This brings to mind Dworkin’s discussion of Joan of Arc:

there was no carnal desire felt [by men] in the presence of [Joan’s] beauty [although that beauty was] female by definition…. This brings with it the sense that it was physically impossible to do it; her body was impregnable…. Joan accomplished an escape from the female condition more miraculous than any military victory: she had complete physical freedom, especially freedom of movement — on the earth, outside a domicile, among men. She had that freedom because men felt no desire for her or believed that “it was not possible to try it.”

The analogy isn’t perfect; Edward wants Bella sexually, and as a vampire he finds her blood especially attractive (“You are exactly my brand of heroin” he says.) Joan mystically shuts down male desire, thus becoming herself masculine; Bella on the other hand inflames desire, becoming all the more stereotypically female. But if Dworkin would no doubt see Twilight as a self-defeating fantasy of objectification, the fact remains that neither Edward nor anyone else can get inside Bella — and this fact eventually allows her, at the climax of the final book in the series, to save her family and change the geopolitical balance of the vampire kingdom. For both Dworkin’s Joan and Meyer’s Bella, virginity is power.

So if Dworkin and Meyer are chattering on about the wonders of virginity, that must mean they hate sex, right? This is certainly the mainstream vision of Dworkin,— her critics often claim that she believed that all heterosexual sex was rape. Though she explicitly denied that, her take on sex is hardly a cheery, rah-rah, Susie Bright one. As she says in Intercourse

With intercourse, the use is already imbued with the excitement, the derangement, of the abuse….Intercourse as an act often expresses the power men have over women. Without being what the society recognizes as rape, it is what the society — when pushed to admit it — recognizes as dominance…..There are efforts to reform the circumstances that surround intercourse….These reforms do not in any way address the question of whether intercourse itself can be an expression of sexual equality.

So intercourse isn’t quite rape…but it is dominance, is inherently unequal, and it is not subject to reform. Intercourse oppresses women.

Again, you can see why people think that Dworkin has a problem with, as she often calls it, fucking. And yet, the truth is almost the opposite. Dworkin isn’t down on sex because she hates it. On the contrary, she hates sex as it is practiced not only because it defiles women, but because it defiles sex itself. When sex is rooted in self-knowledge and love it becomes, she says,

a complex and compassionate passion…. Fucking as communion is larger than an individual personality; it is a radical experience of seeing and knowing, experiencing possibilities within one that has been hidden.

Behind and in between Dworkin’s condemnation of fucking there is this other vision of sex as a sacrament; the idea that intercourse is an expression of the bonds between loved ones and is therefore holy. The introduction of dominance, hatred, hierarchy, and cruelty into sex is for Dworkin a kind of blasphemy; an original sin, if you will. Intercourse for Dworkin is always already corrupted, evil because, in some unknown place and in some unknown way, it was first good.

women have wanted intercourse to be, for women, an experience of equality and passion, sensuality and intimacy. Women have a vision of love that includes men as human too….These visions of a humane sensuality based in equality are in the aspirations of women; and even the nightmare of sexual inferiority does not seem to kill them. They are not searching analyses into the nature of intercourse; instead they are deep humane dreams that repudiate the rapist as the final arbiter of reality. They are an underground resistance to both inferiority and brutality, visions that sustain life and further endurance.

They also do not amount to much in real life with real men.

Dworkin won’t embrace the vision…but she still sees it. Which makes me wonder, if after all, she might not have found something to respond to in Twilight. In the last book of the series, Breaking Dawn, Bella is finally transformed into a newborn vampire, with physical strength that is (for a time) even greater than Edward’s. Suddenly it’s she who has to be careful not to hurt him when they embrace. Before the transformation, she was afraid that the elimination of the differences between her and Edward would spell an end to their passion; he would no longer find her soft or warm, no longer feel the pull of her blood calling him. In other words, she worries that becoming strong will make her unfeminine. But that’s not what happens at all.

He was all new, a different person as our bodies tangled gracefully into one on the sand-pale floor. No caution, no restraint. No fear — especially not that. We could love together — both active participants now. Finally equals.

In her essay in the Atlantic about the Twilight series, Alyssa Rosenberg argues that the vampirized Bella “cuts even the romance buffs out of the equation” as Meyer rambles on and on about how Bella can now see Edward like never before and appreciate him in ways beyond the merely human. “Meyer is telling [her audience] that they are literally incapable of seeing through Bella’s eyes,” Rosenberg notes, as if this were a bug. But, as Dworkin could tell her, it’s a feature. Intercourse with men in this world is inherently unequal, and therefore inherently flawed. There is a dream, though, that things can be different. Or, as another imaginer of other worlds and other loves once put it, “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.”

The transformation Bella experiences is not just personal; it’s social. On the surface, Meyer’s fantasy is of a traditional patriarchy. The Cullens are an extended family living under one roof led by a benevolent father. In addition, the book resolutely champions the iconic conservative social issue when Bella refuses an abortion despite the fact that her pregnancy endangers her own life. Though this kind of conservatism is usually seen as denigrating women, Andrea Dworkin had another take. In her 1983 book Right Wing Women, she argued that conservative social arrangements actually offered women some modicum of protection and dignity.

Right-wing women consistently denounce abortion because they see it as inextricably linked to the sexual degradation of women. The sixties did not simply pass them by. They learned from what they saw. They saw the cynical male use of abortion to make women easy fucks…. Right-wing women see in promiscuity, which legal abortion makes easier, the generalizing of force.

Thus, for Meyer, the ultimate expression of Bella’s virginal inviolability is her decision to have her child — a decision whereby she refuses to allow sex to become inconsequential.

But while Meyer is in some sense a proponent of traditional (and Mormon) values, in another sense turning into a vampire involves a rearrangement of familial relationships which can only be described as perverse. The Cullen vampire household is composed of a bunch of married couples who all also see themselves as the children of Carlisle Cullen — so in becoming Edward’s wife, Bella also becomes virtually his sister. Bella’s child, in perfect horror movie tradition, grows at a superfast rate — and is barely out of the womb before she “imprints” on Bella’s best friend and former suitor Jacob. Meyer swears up and down and all around that there’s nothing sexual about this Oedipal imprinting…but even Bella herself finds that hard to believe.

In fact, if the land of vampires is an Eden, then it makes sense that (except for that one about biting the red apple) taboos no longer apply. And this too resonates with Dworkin — particularly with the writing of one of her chief inspirations, the radical feminist Shulamith Firestone. In The Dialectic of Sex, Firestone argued that:

without the incest taboo, adults might return within a few generations to a more natural “polymorphously perverse” sexuality, the concentration on genital sex and orgasmic pleasure giving way to total physical/emotional relationships that included that. Relations with children would include as much genital sex as the child was capable of…. Adult/child and homosexual sex taboos would disappear, as well as nonsexual friendships…. All close relationships would include the physical, our concept of exclusive physical partnerships (monogamy) disappearing from our psychic structure as well as the construct of a Partner Ideal.

Meyer’s vampiric family is, then, in its own way, a kind of prelapsarian feminist utopia, pointing on the one hand to a stable, benevolent society in which all can live safe from the threat of sexual violence, and on the other to a world of libidinal overflow in which staid restrictive rules are smashed in an onrush of egalitarian ecstasy. Vampires, significantly, experience unchanging, never-ending passion — Bella and Edward can fuck monogamously forever without ever tiring or growing bored. And so they will every night for the rest of their eternal lives…though every morning they pause to go to hang out with their family in sort-of-bourgeois domestic bliss.

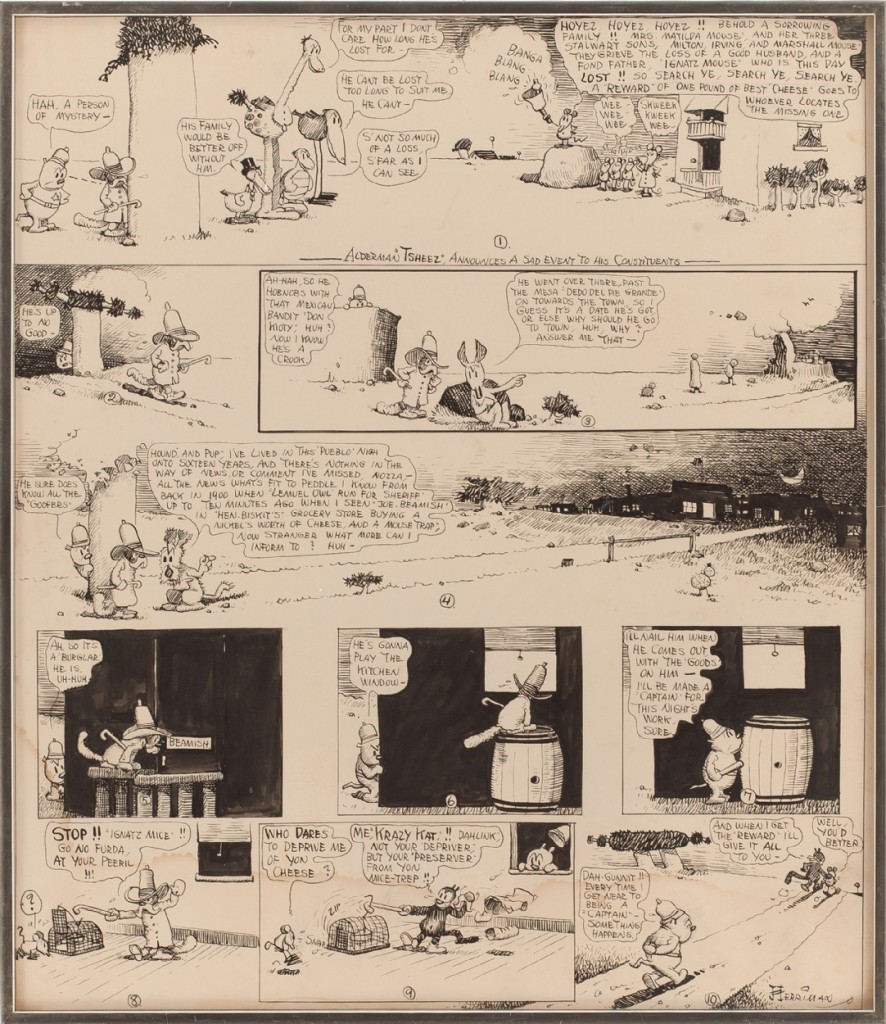

In Intercourse, Andrea Dworkin actually has some things to say directly about vampires. Talking about Dracula, she writes:

vampirism is — to be pedestrian in the extreme — a metaphor for intercourse: the great appetite for using and being used; the annihilation of orgasm; the submission of the female to the great hunter…. While alive the women are virgins in the long duration of the first fuck…after death, they are carnal, being truly sexed…. The new virginity is emerging, a twentieth-century nightmare: no matter how much we have fucked, no matter with how many, no matter with what intensity or obsession or commitment or conviction (believing that sex is freeom)…we are virgins, innocents, knowing nothing, untouched unless blood has been spilled…this elegant bloodletting of sex a so-called freedom exercised in alienation, cruelty, and despair.

For Dworkin, then, Dracula is the ultimate profanation of both virginity and sex; a reimagining, in fact, of one as the other, and both as death. Instead of virginity leading to autonomy, it becomes just another fetish, to be consumed like all others. Instead of sex being a sacrament of love and connection, it becomes a form of “freedom” from connection, an alienated desire which feeds on itself. Vampirism is a way to make intercourse penetrate virginity, corrupting freedom without allowing for love, leaving only a life in death. It’s sex as consumption.

Stephenie Meyer’s vampires, though, don’t swallow Bella’s virginity. On the contrary, the point about the vampires seems to be that they can have sex and still remain virgins, inviolate and unchanging. After Bella has sex, both really and through the metaphor of being turned into a vampire, her power to stay safe in her own mind expands, until she can shield others from psychic invasion the way she shields herself. And at the very end of the book she gets the best power of all; the ability to let Edward read her thoughts when she wishes. Eternally loving, equally superhuman vampires joined in a monogamous relationship consummated by a perfect meeting of the minds. That’s a kind of intercourse maybe even Andrea Dworkin would have approved of.