This is the first in a series of essays this week about The Wire. (David Simon bless us, each and every one.)

Season one laid the framework – the main problem in Baltimore (and, by extension, all major U.S. cities) is drugs. It is a problem because people are poor, the police department is inefficient and corrupt, and the drug organizations can be pretty solid in their business practices (much more so than my office, even if my office were allowed to kill people, which would admittedly change the paradigm, perhaps for the better). Season two is an exercise in correcting any misperceptions we might have developed from season one – to whit, it isn’t just poor black people who do illegal things. It’s also working class white people. Season three expands on that to make sure we understand that business people and politicians are also corrupt.

Having made these points, The Wire pulls back in season four for the wide angle shot: inner city kids. You might have gotten through the first three seasons without feeling that everything was hopeless – depressingly, unutterably, I want to run out into traffic right now hopeless – but I guarantee you won’t finish season four with that kind of feckless optimism intact, even if you watch each episode, as I did, while flipping through bright and shiny European fashion magazines. (Kinukitty endeavors to seek balance in all things.)

Then, as you lie panting and exhausted, washed up on the shoals of abject despair by the unrelenting bleakness of season four, season five arrives to provide some respite. Everyone is still corrupt and characters are still dropping like flies – some of which is quite dismal indeed – but this time the focus is on the newspaper, and we don’t really give a damn about that.

The Wire is not as simplistic as my drive-by summary makes it sound. Its reach sometimes exceeds its grasp, but this series was remarkable in its nuanced approach. The conceptualization, writing, and acting are all consistently – sometimes very, very good. It gives a great background on how ghettos, drug organizations, unions, schools, politics, police departments, and city government really work, and one only rarely wishes they’d climb down off the soapbox and perpetrate some character development and/or plot, already. All these institutions are interconnected, and the people within them, too, and the five seasons of the Wire run down these connections in sometimes subtle and often realistic ways. The actors are believable. I sometimes found myself thinking about plot points or scenes from the Wire as I tried to fall asleep at night.

I have never seen a television show explicate a complicated situation so thoroughly. I was shocked to watch it happen. When I started watching season one, I couldn’t believe this wasn’t the most popular show that had ever been broadcast. It has everything – action, truth, a brilliant and charismatic but out-of-control alcoholic Irish detective. I finally saw the problem, though. I got something important from this show; entertainment, yes, but also understanding. But too much understanding petrifies (quoth James Merrill). I was sodden and hopeless with it. I came to the end of season five feeling like I’d had a melodramatic and rancorous love affair. I’d gotten things out of it I wouldn’t want to forget, but at the same time I was tired and bedraggled and very much ready to call it quits.

I watched the entire series in one stuttering, intermittently obsessive sweep. It took me about three months. This is an unheard-of level of commitment for me, and I felt like I’d accomplished something. And the surprising thing is, I did. I thought thinky thoughts, and I put things together thinkily. As it were. Things I hadn’t quite put together before. Sort of like when you go to several different neighborhoods in a big city, and then you unexpectedly drive on a street you’ve never taken before and find out that it goes through all those neighborhoods, and now you understand how they fit together. (This happened to me recently, by the way. You can take Roosevelt to Halsted, drive through the UIC neighborhood, and you’re in Pilsen! I had no idea.)

In the months since I’ve been parted from the Wire, I’ve been trying to figure out how I could possibly write about it. Because, like I said – all that thinking. Not necessarily thinking that would impress anyone else, but an interesting diversion for me. I was tempted to talk about the last season and the way newspapers work, because I worked at a newspaper, and while the perfectly insightful and never profane news editor was way, way too good to be true, and, as much as I hate to say it, the dumb, smug editor in chief was too dumb to be true, overall, the newspaper scenes made me writhe in an agony of painful recognition. I have also worked with city governments, and that part of the civics lesson felt pretty spot on, too. What I have settled on, though – and only about seven hundred words into the essay – is season two, and the unions.

Here’s what happens. Container shipping has changed the nature of dock work, and the harbor in Baltimore needs a major improvement to make it ideal for the way shipping works today. As a result, the stevedores – all union workers – sit around most days and wait for work. They do not sit around and wait for work in a cheerful, “Ah, I don’t need to work because I have a union job!” sort of way, either. The days are gone when these men, who have a high school education or less and no specific skills, can provide a comfortable living for their families – or much of a living at all. The union president, Frank Sobotka, is doing everything he can to get legislation passed for that harbor improvement, and most of what he’s doing is illegal or immoral. He’s bribing people, dealing with organized crime, working with lobbyists. Among other endeavors, the organized crime guys supply most of the heroin in Baltimore by smuggling it in through the harbor. This connects us neatly to the Baltimore detectives and drug community of which we grew so fond in season one.

Here’s what happens. Container shipping has changed the nature of dock work, and the harbor in Baltimore needs a major improvement to make it ideal for the way shipping works today. As a result, the stevedores – all union workers – sit around most days and wait for work. They do not sit around and wait for work in a cheerful, “Ah, I don’t need to work because I have a union job!” sort of way, either. The days are gone when these men, who have a high school education or less and no specific skills, can provide a comfortable living for their families – or much of a living at all. The union president, Frank Sobotka, is doing everything he can to get legislation passed for that harbor improvement, and most of what he’s doing is illegal or immoral. He’s bribing people, dealing with organized crime, working with lobbyists. Among other endeavors, the organized crime guys supply most of the heroin in Baltimore by smuggling it in through the harbor. This connects us neatly to the Baltimore detectives and drug community of which we grew so fond in season one.

I do not come at this plotline from a neutral perspective. I come from a blue-collar, pro-union background, and although I’m not from Baltimore, I knew those dock workers. There were middle-age and up men who looked older than they were from a life of working hard, real physical labor, and from not knowing how they were going to take care of their families any more now that their livelihood was drying up. And there was that generation’s progeny, idiot and otherwise – the guys I didn’t want to date in high school, partly because whatever else happened to me, I did not want to wind up married to one of those boys. I already knew how that story ended. Anyway, my point is that the Wire presented the dock workers just right. If you are a product of that kind of working class background, you will recognize it. If you are not, you can watch it and gain a more thorough understanding than you can from listening to Bruce Springsteen songs.

Unions are both magnificent and corrupt, and the Wire explains this well, even if it does kill off a dozen Russian hookers in the first episode to make the point. Which seems excessive, doesn’t it? Well, these things happen. The union president is in bed with some very bad people (I find myself talking like that when I refer to the Wire; it has a very satisfying noir-ish slang quotient), but he’s helping them smuggle their drugs and their hookers for a good cause – if he can just get this legislation passed, his family and friends a neighbors will have work again. Then they can drop this organized crime wheeze and get back to their jobs, and everyone can keep their luxuries like houses and cars and food and education and health care. Well, it doesn’t work out. None of it. And that should be good, since corruption is bad and if you drive with corruption, we all lose, or something like that. Nobody wins, though. Instead of the harbor jobs, we get another manicured patch of badly constructed luxury condos. The hookers are still dead, and the heroin is still selling. Not much of a victory.

I think this arc is generally seen as sympathetic toward the unions. At least, those are the informal findings of my highly unscientific study of the issue (to wit, asking the one other person I know who’s seen the show – that would be Noah). After all, the union boss winds up being a sympathetic character. Dying for his sins, and all – voluntarily, even – I mean, that’s a pretty high standard. I forgive him, anyway. And you do come to see the union guys as people, rather than caricatures of lazy entitlement. You see them trying to take care of their friends and family, and you see how frightened they are about what the future holds (or doesn’t), and how much they want to work. In my experience, this is in fact the way it is. Just like ’70s country radio.

I am no longer working class, though. My father’s grinding, exhausting union job made it possible for me to grow up in a small, kind of depressing but safe and well-equipped home (there was always a nice television); to attend school without having to worry about working to help support the family; and thus to have enough space to dream of something else, and enough backup to achieve it. I have never held a union job, and the sum total of physical labor I’ve done amounts to bussing tables and waitressing when I was in college. There’s a point here – bear with me. One of the most important questions thrown out in season two is when Sobotka talks to his lawyer, a man he grew up with. Frank appeals to the man on this basis, and the lawyer points out that he went to law school and made something of himself, while Frank and the rest of the union guys just clung to what they knew, ignoring the signs that it wasn’t going to last.

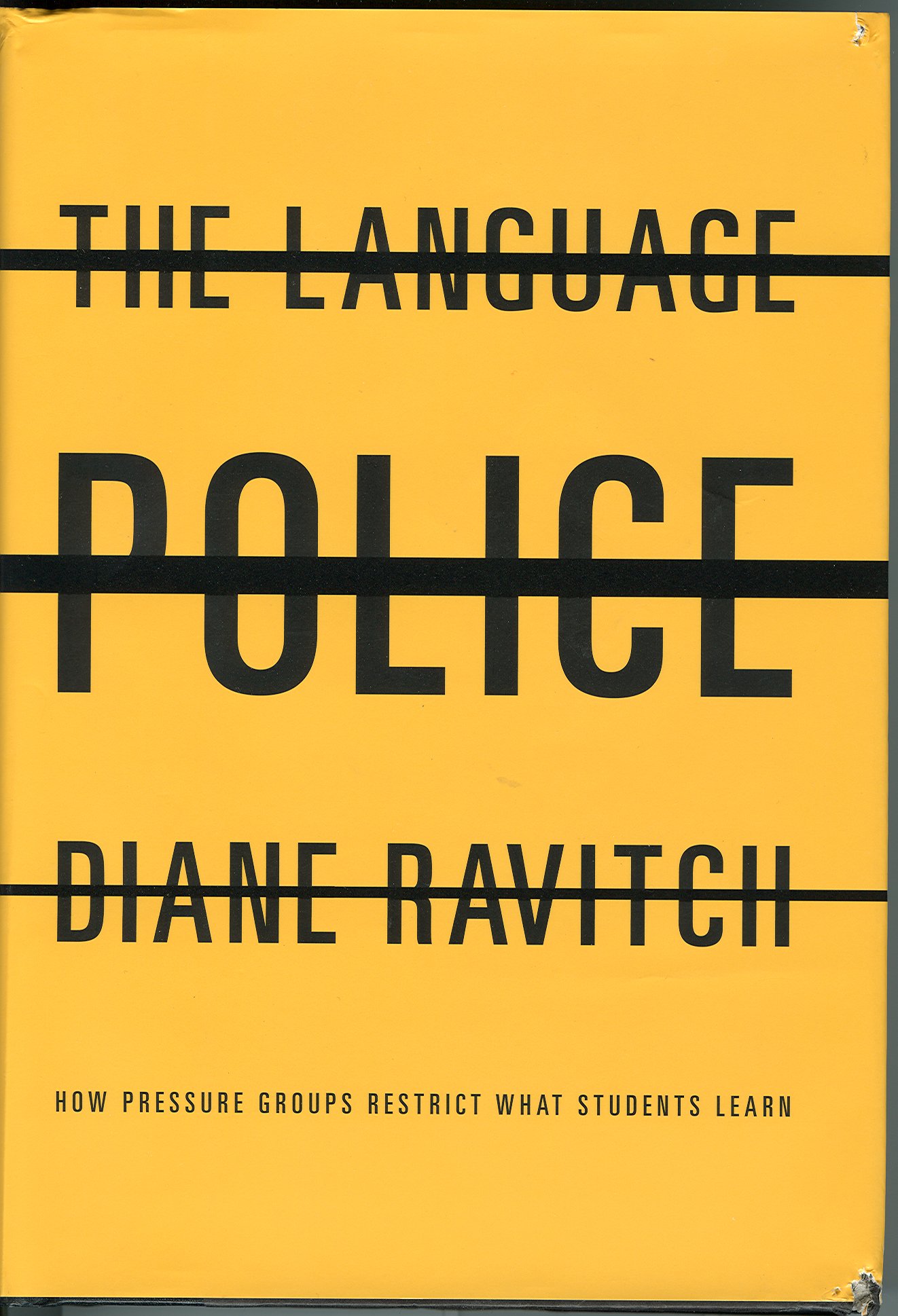

And when I was watching that scene, my emotional reaction was “Yeah!” Because I have some buttons, you know? Recognizing the union guys was not exactly a joyous reunion for me. And beyond the intrinsic importance of my personal reaction, there are a slew of policy initiatives about this shit. Blue-collar workers are being told to go back to school and retool, and many arguments imply (or flat out state) that these idiots should have seen the writing on the wall long ago. So, on the one hand, yeah – go to college, you intellectually lazy bastard. Become a lawyer, like the rest of us. On the other hand – seriously? How does somebody who’s never seen this “go to college and become a lawyer” stuff in action make it happen? How do you do it if you don’t know how it works and you don’t have parents, etc., who went to college and know how it all works? How do you pay for it when you’re making forty thousand a year? And how does a whole class of people do it? And if they don’t do it, what happens to them? Well, that one is pretty easy. Most of them sink from working class to working poor. Or just poor.

It is far from being an abstract question, or a dramatic exaggeration. Look at what Scott Walker is doing in Wisconsin. He sees this as the moment to start knocking down the dominos. If state workers can be stripped of their collective bargaining powers, that takes out the largest group of union workers left in the United States. And it’s not an unpopular stance – everyone has heard of the excesses perpetrated by the unions. It’s easy to take that rhetoric at face value and say, yeah, those guys have it too good. Fuck them. But if you look at the union workers as people – the way the Wire forces you to – the issue gets murky.

___________

Update by Noah: The entire Wire Roundtable is here.