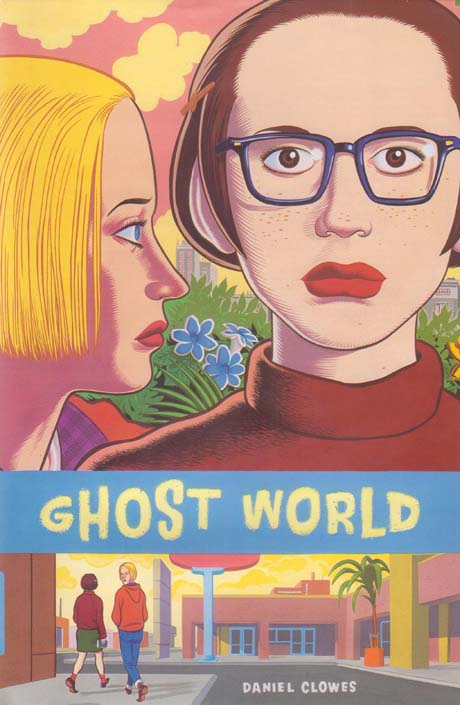

I was interested in setting up a Ghost World roundtable because it’s a book I’ve had mixed feelings about. Well, that’s not exactly right. I’ve always pretty much hated it, actually. But I’ve had some trouble figuring out why I hated it. Which is unusual for me; as a rule my bile flows fairly glibly. I mean, yes, there are some loathsome aesthetic choices — the heinous blue-green spot color being the most obvious. Beyond that, though, I’ve never been able to quite wrap my head around what about the book so thoroughly irritates me.

In this regard,Kinukitty’s post Charles’ essay and Richard’s post have been helpful. Though kinukitty disliked the book, Charles liked it, and Richard had mixed feelings, their reactions actually have a good bit of overlap. For all of them, the book and its characters are defined in large part by absence. Kinukitty says of the characters “I don’t recognize them as high school girls, but that is probably secondary to the fact that I don’t even recognize them as human. They are not so much characters as collections of anecdotes that are intended to be cool and ironic… I think Ghost World is unpleasant in a way that winds up being pointless because there’s no there there.” Richard notes that Enid eventually heads towards adulthood, but that she displays “a maturity without content, which invites that the reader fill in the blanks with their own experiences.” Charles comes at a somehwat similar point from a different angle, arguing that for Enid, “Mass culture has even detached us from our detachment.” In other words, the book’s pointlessnes and Enid’s lack of a center is, for Charles, thematized; it’s an example of our modern, or postmodern dilemma. Ghost World is a world where there is no meaning; where you can’t even recognize others as human, where we’re all just collections of anecdotes, alienated from our own stories.

I think Charles has also made a very astute point — though not quite the one he intends — in linking Ghost World to the work of John Barth. Clowes is often discussed in terms of filmmakers like David Lynch, I think, but he’s always struck me as being more allied with contemporary fiction — not least because of his flatness. Lynch, for all his auteurishness, has a lot of pulp at his heart; he likes the flamboyance of horror or heist films or psychological thrillers. He may make films about emptiness and the break-up of identity, but the films themselves are filled with pyrotechnics and a weird kind of life. They’re not a blue-green blank.

Literary fiction, on the other hand, often is. “Middle-aged academic types” as Charles quips, abound; it’s a genre of mid-life crisis. And indeed, Barth’s The End of the Road, from Charles description, sounds very much like…well, here’s what Charles says about it:

Horner is a middle-aged academic type who’s managed to think himself into a hole, not seeing any potential action as better grounded than another – sort of an infinite regress of self. Thus, he’s sitting in a bus station in a state of existential paralysis, not able to even come up with a good reason to get on a bus and leave his former (non-) life behind.

That’s tricked out with intellectual filigree, but basically it’s a mid-life crisis, right? Garden variety despair at getting halfway through your existence and realizing you haven’t done all that stuff you wanted to do when you were a kid; you’re not on top of the world, you’re just some bourgeois scmuck like every other bourgeois schmuck, so you sit there, unable to go forward, unable to go back. Okay, now, hurry up and write a novel explaining that it’s not just you who’s lame — it’s a universal, existential condition!

So hold that thought, and let’s consider Enid for a moment. Enid is in almost every respect an extremely odd teenaged girl (as kinukitty points out). She seems acidly alienated from pop culture and music. She’s uninterested in discussing her crushes, or, indeed, discussing enthusiasms of any sort. She has an extremely guy-like instrumental approach to sex, based largely on scoring points and talking to her friends afterwards. And she turns for solace, not to booze, or drugs, or sex, or crushes, or pop songs, or movies, but rather to totems of her childhood; random theme parks she visited as a kid, random toys; half-remembered kids songs. Enid is desperately nostalgic for her youth — which is more than a little weird when you’re only, what? 17?

Oh, yeah, and she has a fascination with creepy borderline psychos. Who are older. And male.

Not that it’s impossible that a teenaged girl would act this way, of course — people are different after all — and certainly lots of young girls are fascinated with creepy older guys. But…well, for example, Ariel Schrag is more or less in Enid’s bourgeois demographic. And her adolescence, based on her autobiographical comics, was certainly filled with anguish of various sorts — her parents divorced, she went through a painful process of questioning her sexual identity and she had a number of extremely traumatic relationships.

But…Ariel didn’t live in a ghost world. She had lots of serious problems, but they were problems that you have when you’re young — which is to say they were problems caused by not being able to understand, or process, or sort out a cascade of emotions and desires. Ariel’s difficulty wasn’t that her world was fading out, but that it was too sharply coming into focus, and there was too much of it. It’s the intensity of her emotions — her crushes, her attachments to friends, and, indeed, her attachment to her art — that makes her life a misery. Sometimes. And, then, at other times, that same intensity becomes a source of strength and beauty and excitement.

Now, that second bit doesn’t have to happen necessarily, and doesn’t for a lot of adolescents. Youth can be great (which is why people romanticize it at times) but it can also really suck, and the sucking can easily outweigh the good stuff, and does for lots of people. But the point I think is, when adolescence is miserable (as it absolutely can be) it tends to be miserable the way adolescence is miserable, and not miserable like middle-age.

Ariel Schrag wrote her autobiography when she was an adolescent, and that’s how it reads. Dan Clowes wrote Ghost World in his mid-thirties…and that is so, so, so how it reads. Enid, it seems to me, makes most sense not as an accurate portrayal of a teen girl, but rather as an accurate portrayal of a thirtysomething man enjoying himself by pretending to be a teen girl.

And, indeed, as that, Ghost World is undeniably kind of brilliant. Most of the intellectual content of the book is little more than the clichéd crankery of the past it hipster, bitter that he’s no longer up on all the latest bands, pining for his youth while simultaneously loathing and desiring the young. Put those sentiments in the brain of a college professor and you’ve got just another novel by John Updike…or, perhaps, John Barth. But hand the sentiments off to young girls — that’s kind of genius. Have the girls sneer at Sonic Youth for you; have the girls moon after the detritus of their youth; have them say of each other, with just a touch of condescension, “You’ve grown into a very beautiful young woman.”

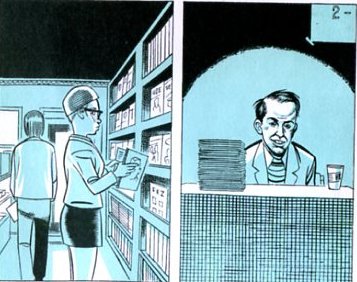

Perhaps the most emblematic moment in the book, in this respect, is when Enid meets (a thinly disguised) Clowes himself. This is, to the best of my recollection, the only time in the narrative that Enid expresses an unironic connection to, or enthusiasm for, any piece of contemporary pop culture. Yet, when she sees the “real” Clowes, she is disappointed because nobody else has come to see him and he is “like this old perv.”

Clearly this is supposed to read as self-effacement on Clowes’ part. But I wonder. Enid’s initial fascination (which is in part sexual) is certainly a fairly familiar creator fantasy (“she loves me for my art!”) But even more than the enthusiasm, it seems to me that the disappointment is a kind of sublimated self-aggrandizement. After all, Enid’s let-down is only really possible because her interest in Clowes, like all of her interests, is without content. We never learn what she likes about faux-Clowes, or what it is in his books that inspires her. Who is Enid? She’s no one, a ghost without purchase on her world or her culture. And why is she no one? Whose ghost is she?

Surely it’s significant that, as this sequence suggests, while Clowes can imagine Enid, Enid can’t imagine Clowes. Indeed, the page reminds us subtly that it is Clowes calling Enid into being; we see her from his perspective first, and only then can she see him. Enid’s self isn’t there not because that’s the way it is for all of us in this sad state of late postmodernity, but simply because her self isn’t hers. She’s somebody else’s mid-life crisis, there to buttress another’s existential vacuum with the weight of her own nonentity.

______________

Update: Suat’s contribution to the roundtable is now up.