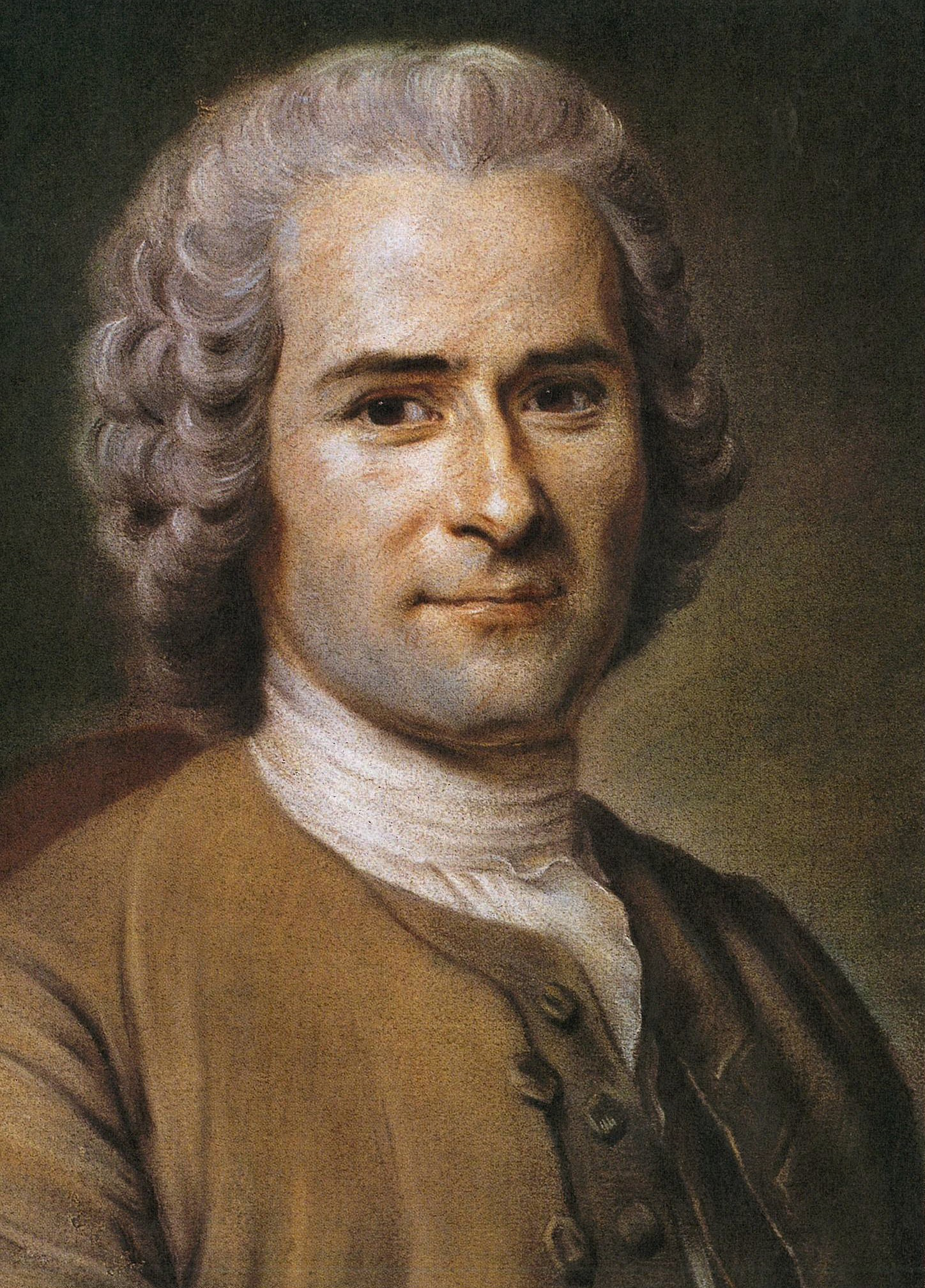

It happened that in the midst of the dissipations attendant upon a London winter, there appeared at the various parties of the leaders of the ton a nobleman, more remarkable for his singularities, than his rank. He gazed upon the mirth around him, as if he could not participate therein. Apparently, the light laughter of the fair only attracted his attention, that he might by a look quell it, and throw fear into those breasts where thoughtlessness reigned. Those who felt this sensation of awe, could not explain whence it arose: some attributed it to the dead grey eye, which, fixing upon the object’s face, did not seem to penetrate, and at one glance to pierce through to the inward workings of the heart; but fell upon the cheek with a leaden ray that weighed upon the skin it could not pass.

—from The Vampyre: A Tale, by John William Polidori

x

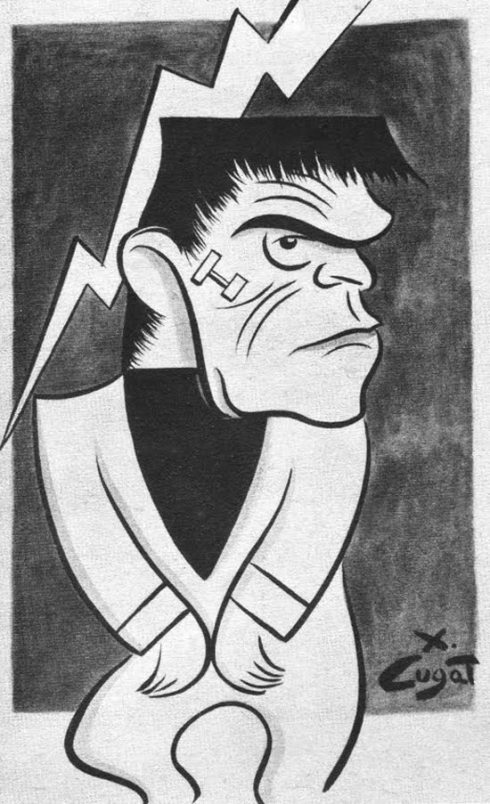

One summer night in 1816, a group of friends gathered in the Villa Deodati, on the shores of Lake Geneva, and entertained themselves by reading ghost stories. They then determined to write each a tale of horror. Ironically, the two most renowned writers in the party– the poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and George Gordon, Lord Byron — never completed their tasks; while the unknownMary Shelley subsequently wrote the justly famous novel Frankenstein: or, the modern Prometheus (discussed in part1).

One other of the group, John William Polidori (1795-1821) produced another classic of horror fiction: The Vampyre: a Tale (1819). It had enormous success and influence, and contributed to another classic literary incarnation of the superman.

The preceding century had already seen something of a craze for vampires; these, however, were generally the crude monsters of folklore. Polidori changed this characterisation at a stroke. His vampire, Lord Ruthven, was not a freakish peasant ghoul but an elegant aristocrat, at home in the loftiest circles. This conception of the vampire quickly caught on, and would reach its apotheosis at the end of the century in Bram Stoker‘s Dracula. The aristocratic figure with a secret, dark identity also finds its descendants in such superheroes as pulp fiction’s The Shadow and comic books’ Batman.

The Penny Dreadful

One very popular variation on the Ruthven figure was James Malcolm Rymer‘s serial Varney the Vampire: or, the Feast of Blood (1845-1847).

Varney was a prime example of the first true mass medium for fiction: the serial novel, which emerged in the 1830?s.

Novels had been serialised before, of course, but mostly in separate, costly volumes, aimed at the growing middle class. But in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, literacy rates among the labouring classes trended ever upwards. According to a bookseller named Lackington, writing in 1790 England:

The poorer sort of farmers, and even the poor country people in general, who before that period spent their winter evenings in relating stories of witches, ghosts, hobgoblins, &cetera, now shorten the winter nights by hearing their sons and daughters read tales, romances, &cetera, and on entering their houses you may see ‘Tom Jones’, ‘Roderick Random’ and other entertaining books stuck up in their bacon racks…In short all ranks and degrees now READ.

( Of course, Lackington is also describing here the gradual eclipse of folk culture by a manufactured popular mass culture.)

The process of advancing literacy culminated, by the nineteenth century’s end, in universal free public education throughout Europe and America. This created a new mass market for literature, and the latter tended decidedly to the sensational.

In addition, the development of the steam press allowed runs of tens of thousands of copies in record time; paper, which theretofore had been made expensively from rags, now was produced from cheap esparto grass and, later, even cheaper wood pulp.

Varney was an early example of the racy, excitement-packed publications known as penny dreadfuls or penny bloods. As these names show, they were cheap and they were laden with gore. Often they celebrated the adventures of famed criminals like the highwayman Dick Turpin or the cannibalisticSweeney Todd.

(The public, then even more than now, relished a good villain; the working classes– not unreasonably — viewed the police and magistrates with suspicion and hatred. This instinct is centuries old: think of the ballads celebrating the outlaw Robin Hood.)

By the 1850?s, the penny dreadful was largely aimed at working-class adolescents. Cheap pamphlets featuring daring heroes and villains aimed at an audience of juveniles…does it sound familiar? And indeed, the penny dreadful and its American cousin, the dime novel, were direct ancestors of the superhero comic.

And like the comics, the penny dreadfuls were widely condemned for breeding juvenile delinquency:

The six-pen’orth before me include, “The Skeleton Band,” “Tyburn Dick,”, “The Black Knight of the Road,” “Dick Turpin,” “The Boy Burglar,” and “Starlight Sall.” If I am asked, is the poison each of these papers contains so cunningly disguised and mixed with harmless-seeming ingredients, that a boy of shrewd intelligence and decent mind might be betrayed by its insidious seductiveness? I reply, no. The only subtlety employed in the precious composition is that which is employed in preserving it from offending the blunt nostrils of the law to such a degree as shall compel its interference.[…] The daring lengths these open encouragers of boy highwaymen and Tyburn Dicks will occasionally go to serve their villanous ends is amazing. […] Which of us can say that his children are safe from the contamination?

– from James Greenwood’s The Seven Curses of London,1869

Newsvendor.- “Now, my man, what is it?”

Boy. “I vonts a nillustrated newspaper with a

norrid murder and a likeness in it.”

from Punch magazine, 1845

Even Greenwood, however, concedes that the dreadfuls were great enablers of literacy (an argument also advanced today by the defenders of the comic book):

Who says that he is a dunce and won’t learn? Try him now. Buy a few numbers of the “Knight of the Road” and sit down with him, and make him spell out every word of it. Never was boy so anxious after knowledge. He never picked a pocket yet, but such is his present desperate spirit, that if he had the chance of picking the art of reading out of one, just see if he wouldn’t precious soon make himself a scholar?

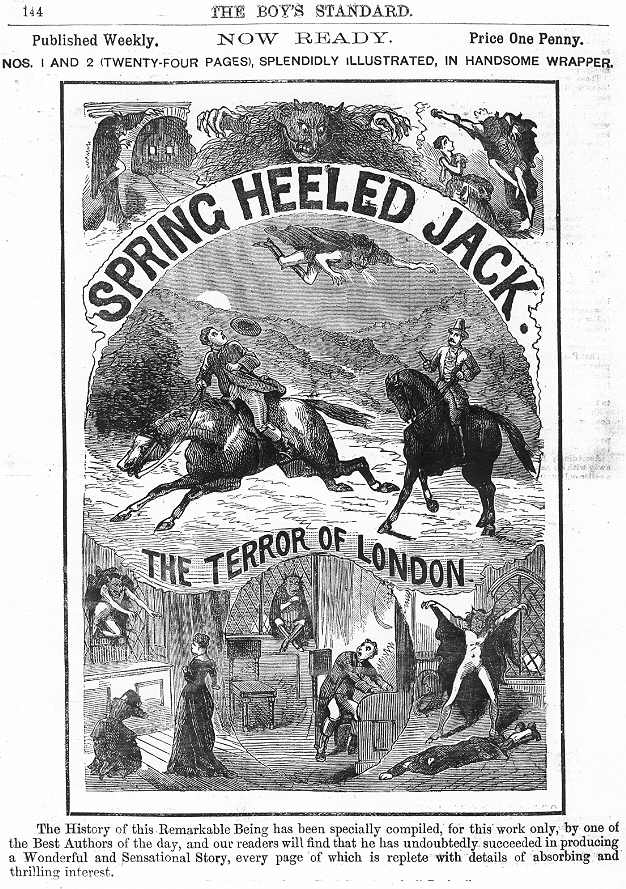

Let’s consider a penny dreadful hero/villain taken from a British urban legend,Spring Heeled Jack.

The eponymous Jack was supposedly a demonic figure that made incredible leaps, breathed flame, and terrorised the population. He was immediately seized on by the twin pillars of sensational fiction, the melodrama theatre and the penny dreadful.

In the ‘dreadful’, Jack Dacre is a young man dispossessed of his rightful inheritance by his villainous cousin. He assumes the identity of Spring Heeled Jack to rob and terrorise the blackguard, and finally to bring him to justice.

A description of his costume:

His dress was most striking.

It consisted of a tight-fitting garment, which covered him from his neck to his feet.

This garment was of a blood-red colour.

One foot was encased in a high-heeled, pointed shoe, while the other was hidden in a peculiar affair, something like a cow’s hoof, in imitation, no doubt, of the “cloven hoof” of Satan. It was generally supposed that the “springing” mechanism was contained in that hoof.

He wore a very small black cap on his head, in which was fastened one bright crimson feather.

The upper part of his face was covered with black domino.

When not in action the whole was concealed by an enormous black cloak, with one hood, and which literally covered him from head to foot.

He did not always confine himself to this dress though, for sometimes he would place the head of an animal, constructed out of paper and plaster, over his own, and make changes in his attire.

Still, the above was his favourite costume, and our readers may imagine it was a most effective one for Jack’s purpose.

– from Spring Heeled Jack: the Terror of London, The Boy’s Standard Weekly

Hmm… an origin story (complete with revenge and justice motivation.) Super power– the ability to leap extraordinary distances. A striking costume with mask and cape. A secret identity. A sidekick (a sailor unfortunately named Ned Chump.) Daring escapes, lashings of violence, justice triumphant in the end. All in serialised pamphlets aimed at adolescents.

Sure sounds like a superhero comic, doesn’t it? And Spring-Heeled Jack anticipates, in many ways, Spider-Man. Both costumed adolescents taken for adults, leaping prodigiously from building to building, hounded by the authorities though secretly fighting for justice…

Of course, not all serials were sensational or aimed at juveniles; Charles Dickens’ serials enthralled all ages and all classes, as published in his magazines Household Words and All the Year Round. And across the Channel, France produced perhaps the greatest adventure serial novelist of all time: Alexandre Dumas.

Monte Cristo: superman

Alexandre Dumas

In 1800, the French newspaper Le Journal des Débats added to its main political section a supplement covering arts and science, and called it a “feuilleton” (“little sheet”). The innovation was much copied all over Europe, and, of course, survives to this day.

Novelists such as Honoré de Balzac and Georges Sand started serialising their upcoming books in the papers. However, the latter were still expensive and thus catered to middle-class tastes in literature.

This would change in 1836, with the launch of La Presse; it sold at half-price compared to its rivals, in fact at a loss. The idea was to maximise circulation and make a profit on paid advertising (a business model that served newspapers well until very recent years.)

By necessity the papers in this new paradigm had to cast their nets as wide as possible in quest of readership, including the newly-enfranchised working classes. They found a spectacularly successful way to build reader loyalty: the serialised novel, or “roman feuilleton”.

These drew upon every resource of suspense, sentimentality, and melodrama to keep the reader panting for the next installment; a recipe later adopted by film, radio and television serials, as well as comic strips and comic books.

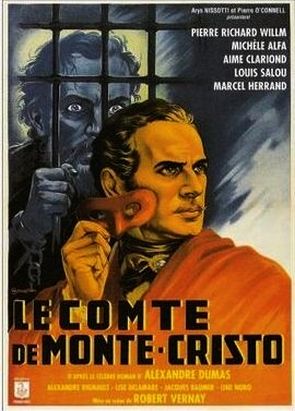

The first breakout blockbuster was doubtless Eugène Sue‘s Les Mystères de Paris, serialised in 1842 and 1843. This sensationalist novel was read by millions worldwide. Its hero, Prince Rodolphe de Gerolstein, succors the wretched and humbles the mighty; Umberto Eco singles him out as a proto- superman, and as the undoubted inspiration for the hero of a classic that enthralls even today, whether in book or film or theatre play: The Count of Monte Cristo.

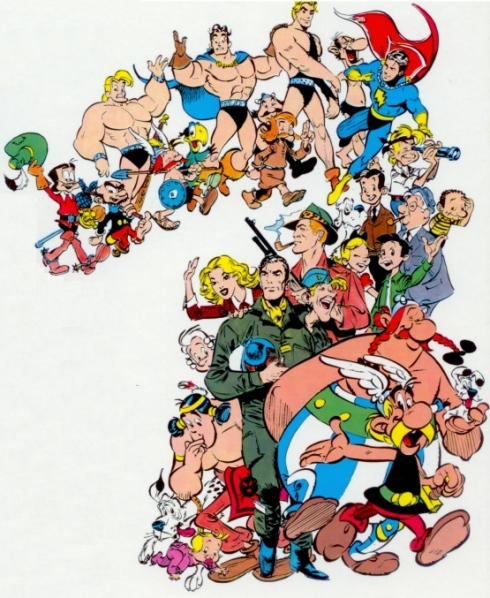

Alexandre Dumas (1802 — 1870) was a writer of astounding industry; the author of 136 books, several of which top the thousand-page mark. Yet despite much hackwork, the vigor and élan of his storytelling have preserved his name to the present day; who has not heard of The Three Musketeers or The Man in the Iron Mask?

Dumas was a regular fiction factory, and routinely employed ghosts to help him — the most notable of whom was Auguste Maquet. Together, they produced The Count of Monte Cristo, perhaps Dumas’ most celebrated novel, serialised from 1844 to 1846.

The Count is a sprawling epic hinging on that most primal wellspring of human action: revenge.

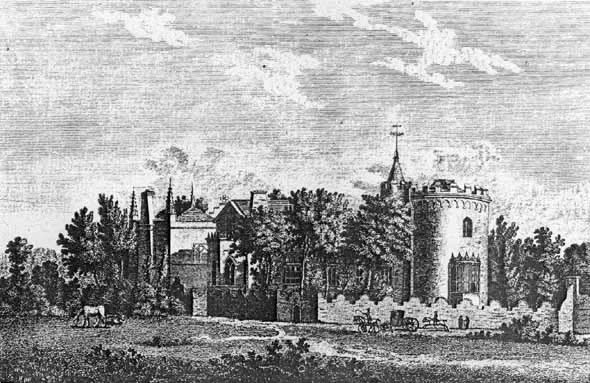

Edmond Dantès is a young French sailor about to take command of his first ship and to marry his fiancée. But a cabal of villainous men forge a letter that seems to prove him a conspirator against the Crown, and he is thrown into a prison cell where he languishes for fourteen years. He escapes by taking the place of his friend and cellmate’s corpse, and is thrown into the sea.

His friend had indicated to him the secret location of a fabulous treasure in a grotto on the Mediterranean island of Monte Cristo.

The island of Monte Cristo

After securing this limitless wealth, Dantes finds out that his enemies have all, over the ensuing years, risen to the summits of power and riches. He vows revenge; Edmond Dantès has died, and is reincarnated as the mysterious, supremely wealthy and powerful Count of Monte Cristo. He makes his way to Paris, and contrives to bring about the ruin, madness, or death of his foes.

Monte Cristo, however, sees himself not as an avenger, but as an implacable agent of divine providence sent to dispense justice among the throngs of humanity above which he has risen. His mastery is complete; nothing can stand in his way; his will is that of the superhuman– of the superman:

“You may, therefore, comprehend, that being of no country, asking no protection from any government, acknowledging no man as my brother, not one of the scruples that arrest the powerful, or the obstacles which paralyze the weak, paralyzes or arrests me. I have only two adversaries — I will not say two conquerors, for with perseverance I subdue even them, — they are time and distance. There is a third, and the most terrible — that is my condition as a mortal being. This alone can stop me in my onward career, before I have attained the goal at which I aim, for all the rest I have reduced to mathematical terms. What men call the chances of fate — namely, ruin, change, circumstances — I have fully anticipated, and if any of these should overtake me, yet it will not overwhelm me. ” –Monte Cristo, chapter 48

Small wonder Antonio Gramsci maintained that Fascists and other worshippers of the superman took their template, not from Nietzsche, but from Dumas! As quoted in Umberto Eco’s Il superuomo di massa, Gramsci points out that “the serial novel replaces (and at the same time favorises) the imagination of the man of the people, it is a true waking dream[…] long reveries on the idea of revenge, of punishing the guilty for inflicted hurts […]“ And today, the bullied kid identifies with Batman beating up thugs that stand as proxies for his tormentors.

To be fair to Monte Cristo, the superman in question comes to doubt more and more the validity of his exalted state and supposedly divine mission; the turning point comes when he beholds that his vengeful machinations have brought about the death of an innocent. Here is the climax of his final confrontation with his odious enemy Villefort:

“There! Edmond Dantès”, said he, showing the corpse of his wife and the body of his son, “there! Look! Are you well avenged…?”

Monte Cristo paled at this horrible sight; he understood that he had just overstepped the rights of vengeance; he understood that he could no longer say:

“God is for me and with me.”

And indeed, Monte Cristo ends by forgiving his last foe standing, the banker Danglars,after tormenting him for days. Forgiveness? Supermen should be made of sterner stuff. Nietzsche would have turned away in disgust.

art by Alex Blum

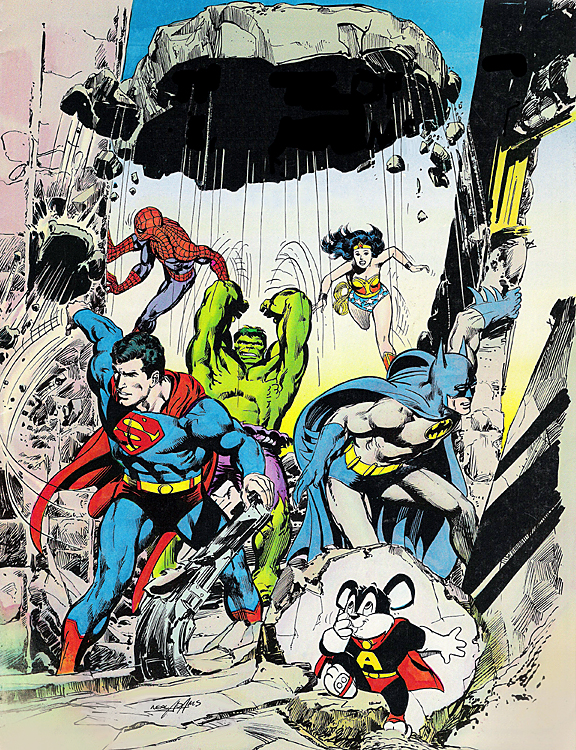

How does Monte Cristo relate to the modern superhero, as Umberto Eco suggested?

He has a traumatic origin story, from which he emerges transformed into a superior being; he has a superpower– and a pretty realistic one– limitless wealth ; a master of disguise, he adopts several secret identities; he worksoutside the law to bring about justice to evildoers.

And, most importantly, he is a fantasy projection with which the reader identifies, the imaginary righter of his own perceived wrongs.

Nonetheless, his final remorse and doubts set him apart from the American superman, who seldom if ever feels such wimpish emotions.

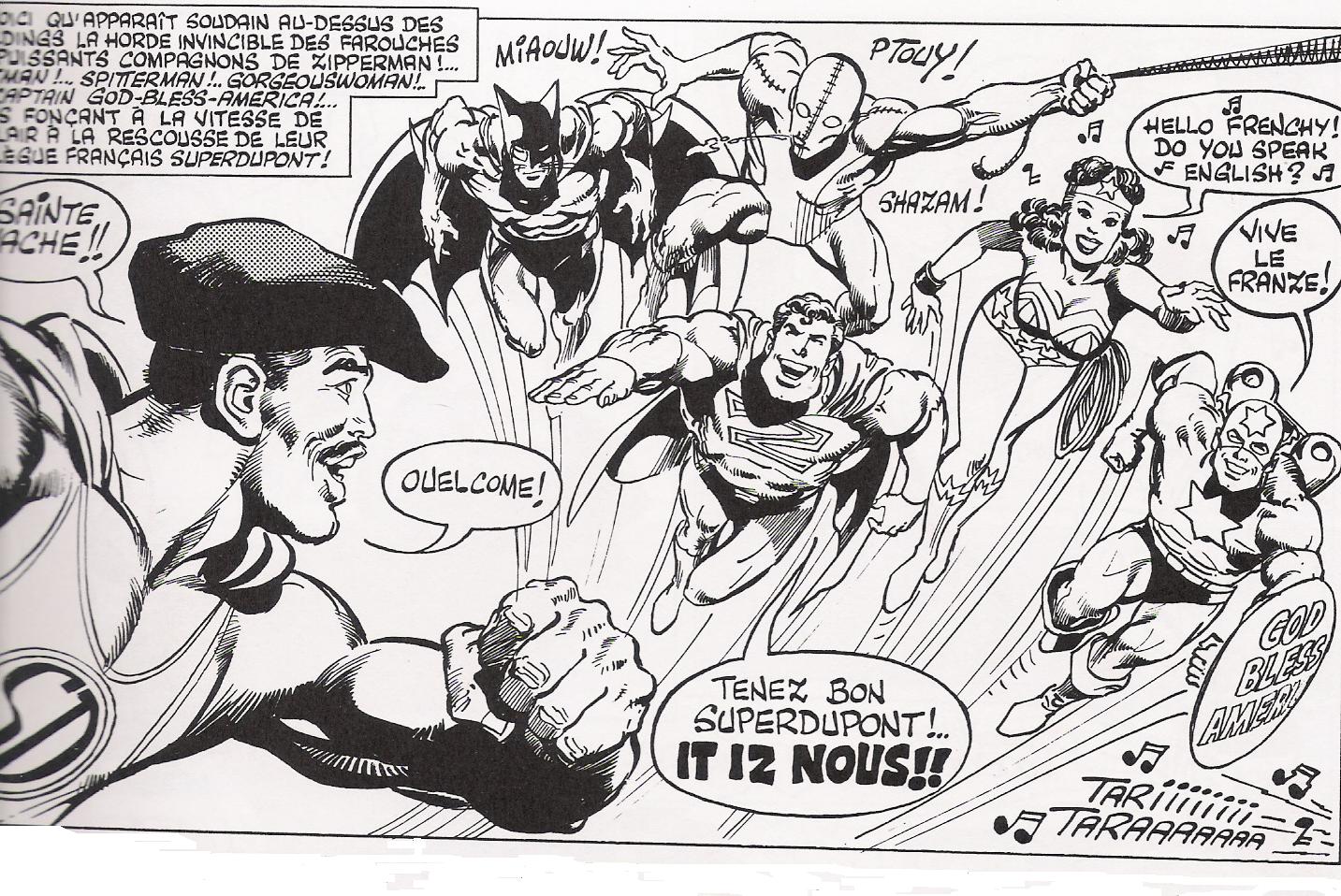

Another reason why the superhero never really took off in old, conflicted Europe– which yet had much to contribute to its mythology…

Art by John Buscema and Ernie Chan

Next: Supermen of Science — Verne and Edison