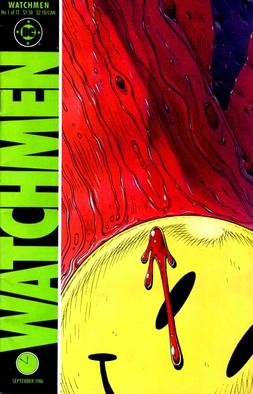

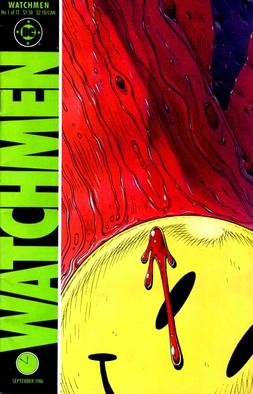

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale was published in 1985. The first issue of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen was published in 1986. Despite that closeness, they’re not two novels that are routinely paired. Which is why I was pleased when a pair of students in my Late 20th Century Fiction course decided to combine them as examples of dystopias. And, even more fun, my students disagree about the definition of “dystopia.”

So here’s round one of their literary match-up.

—Chris Gavaler

Beginning with Thomas Moore’s Utopia, a tradition of idealized societies has existed both in the imaginations of great thinkers and writers as well as in the literary canons of virtually every culture. Yet frequently in these perfect utopian universes, a dark underbelly emerges, characterized by abuses of power, totalitarian regimes, and control of every minutia of a citizens’ lives, usually as an excuse for their protection in the beginning. These types of dystopian universes create environments of fear and isolation, with an evil government and good and innocent citizens. However, what happens in dystopias in which there is no clear oppressor, no direct dichotomy of good and evil? Instead, subtle powers are at work that do not allow for a clear ability to point a finger at the ‘good’ or ‘evil’ power responsible for ‘light’ oppression. In their novels The Handmaid’s Tale and Watchmen, Margaret Atwood and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons grapple with this question of good and evil and create two dystopian worlds that either reinforce the Manichean dichotomy or blur the line between good and evil. Where The Handmaid’s Tale utilizes total dystopian control of its people to further confine and separate them, creating a Manichean dichotomy between good and evil, Watchmen uses subtle manipulation in order to unite the entire world, blurring the line between good and evil. In showing two radically different uses of dystopia, these authors call into question the assumption that absolute control in a dystopia is necessarily evil.

To formulate my argument, I will begin by exploring two definitions of dystopia. I will then examine how The Handmaid’s Tale fulfills Ketterer’s definition of dystopia. Contrastingly, I will delve into the world of Watchmen, and explore the ways that it fits into Greene’s definition of dystopia. Finally, I will examine the good versus evil dichotomies in each of these novels and their relationship to dystopian literature.

Utopia and dystopia are frequently two sides of the same coin, representing idealized societies that are either perfect or move too far in the direction of creating a perfect world. Greene establishes a simple yet effective definition of utopia as “an ideal society” (Greene 2). Unfortunately, these utopias are rarely idealistic and perfect places in practice, even if their ideals are, in theory. In one of the earliest examples of utopian literature, “Thomas More, in his Utopia (1516), conjures an isolated island to describe a better world but one that in hindsight sounds fascist” (2). By blurring the lines between these two genres, Greene demonstrates that utopia and dystopia are on a continuum and lend themselves to blurring the lines of Manichean dichotomies of good and evil.

Dystopian literature is characterized by a multitude of individual genre characteristics, but is pervaded by a sense of oppression via governmental and totalitarian powers. The opposite of a perfect society, a literary dystopia is an “imaginary society that differs from the author’s own, first, by being significantly worse in important respects, and, second, by being worse because it attempts to reify some utopian ideal” (Beauchamp 11). By Beauchamp’s definition, dystopia perverts positive ideals and the world of the author in order to create a plausible society in which there is no freedom from the government. In order to classify novels and stories as dystopian, Ketterer provides a clear framework of the types of features included in the genre: “lack of freedom, the constant surveillance, the routine, the failed escape attempt” (211). In a different vein, Greene claims that dystopian universes are characterized by a distinct “suffocation of independent thought” (2). Greene’s definition of dystopia may include some of Ketterer’s elements, but focuses its attentions on the atmosphere of control and stifling of non-institutionalized thought amongst its citizens. These two definitions, though not always mutually exclusive, serve as useful categorizations for The Handmaid’s Tale and Watchmen.

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale’s government of Gilead contains every element of Ketterer’s definition of dystopia. Though there are some elements of stifling of independent thought, its most salient dystopian features belong to Ketterer’s definition and classify it solidly in the dystopian genre through four specific features.

Firstly, Gilead eliminates freedom from the lives of its citizens. When the Gilead government began, “newspapers were censored, and some were closed down, for security reasons they said. The roadblocks began to appear, the Identipasses. Everyone approved of that, since it was obvious you couldn’t be too careful” (Atwood 174). The government closed down the freedoms of its citizens one by one, slowly taking every semblance of freedom they had in a subtle way, at first. Ultimately, Gilead obliterates freedom by creating roles relating to fertility, and women’s “real name[s have] been erased in favor of the form of ‘Of’ plus the first name, possibly abbreviated, of her Commander” (Ketterer 210). As Offred herself states, “my name isn’t Offred, I have another name, which nobody uses now because it’s forbidden. I tell myself it doesn’t matter. I keep the knowledge of this name like something hidden, some treasure I’ll come back to dig up”(Atwood 84). This removal of names dehumanizes women and forces them to become their proscribed roles, as Handmaids, or “two-legged wombs” (136), Aunts, Marthas, Wives, Unwomen, or prostitutes. By removing agency and proscribing roles, Gilead destroys freedom.

Routines similarly are present in Gilead, from a daily morning walk for the Handmaids, to the Ceremony. The most salient routine of the society is the Ceremony, a brutal moment when the Commander tries to impregnate his Handmaid. Offred does not describe this scene as rape, however, instead calling it “nothing is going on here that I haven’t signed up for. There wasn’t a lot of choice but there was some, and this is what I chose” (94). Through this brutal routine and near sacred ritual, Atwood creates the only alternative a young fertile woman could choose, aside from the oblivion of Unwomanhood. This monthly routine of impregnation, in parallel with other more innocuous routines and rituals, demonstrates the ways that Gilead governs through strict control of its citizens’ freedoms, particularly by organizing their daily lives.

Gilead constantly spies and watches its citizens, as is proven by the many golden eyes found in public places and privates ones, such as the doctor’s office (60), Offred’s room, or on the Soul Scrolls (167). In front of the Soul Scrolls store, Greene’s rules of no independent thought are broken, and readers see the surveillance in place in Gilead. Ofglen, Offred’s walking partner, leans over to Offred and says, “’Do you think God listens,’ she says, ‘to these machines?’ […] In the past this would have been a trivial enough remark, a kind of scholarly speculation. Right now it’s treason,” (168) remarks Offred. Thought and spoken original thought is no longer taken for granted. It is stifled and discouraged through constant surveillance and fear of being taken by the Eyes. To think is treason in Gilead; to birth children is of the highest importance. This government fulfills Ketterer’s category of constant surveillance, and uses it to engage in thought suppression, though that is not necessarily its ultimate goal. Surveillance in Gilead is used to incite fear, not to prevent independent thought.

Finally, The Handmaid’s Tale contains varied escape attempts, including the ending of the novel. There are minor ‘escapes’ found throughout the novel, during which the women of Gilead attempt to communicate with one another while escaping detection. For instance, in the Center where the Handmaids are trained, “in the paint of the washroom cubicle someone unknown had scratched: Aunt Lydia sucks” (222). These clandestine messages, though not directly escape attempts, create distinct groups in Gilead of good and evil. These two categories are even further proven in an actual escape attempt at the end of the novel, when the Eyes come to take Offred. Nick assures her, “It’s all right. It’s Mayday. Go with them” (293). Mayday, signifying a day of rebellion for Gilead, shows the final escape attempt. She must choose to trust the only male in the story not in a position of possession over her and go with the Eyes, not knowing whether or not she should believe Nick. This final attempt, in conjunction with smaller escape attempts found throughout the novel fulfill Ketterer’s definition of dystopia, as people want to leave the evil power regime created by Gilead.

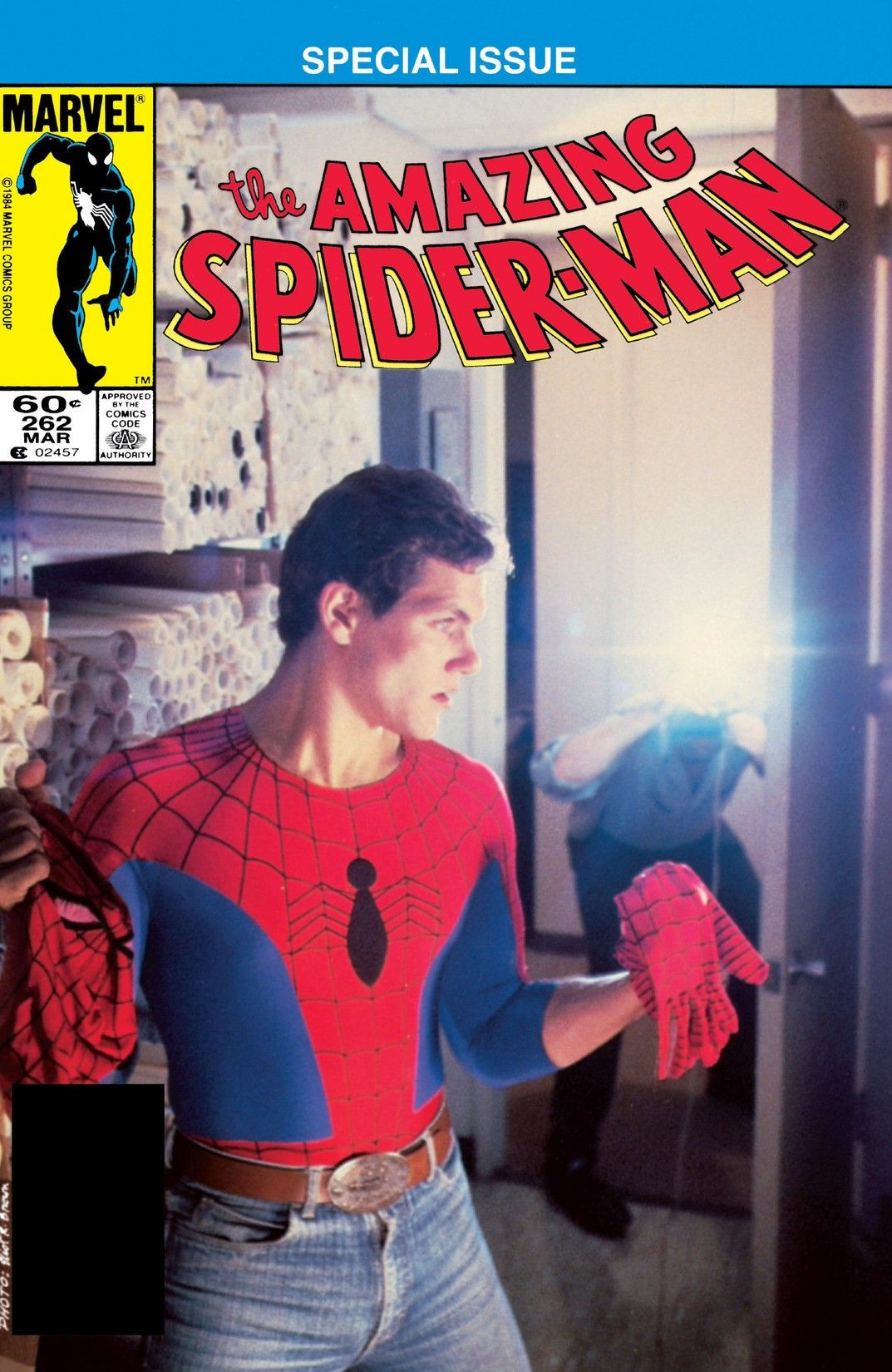

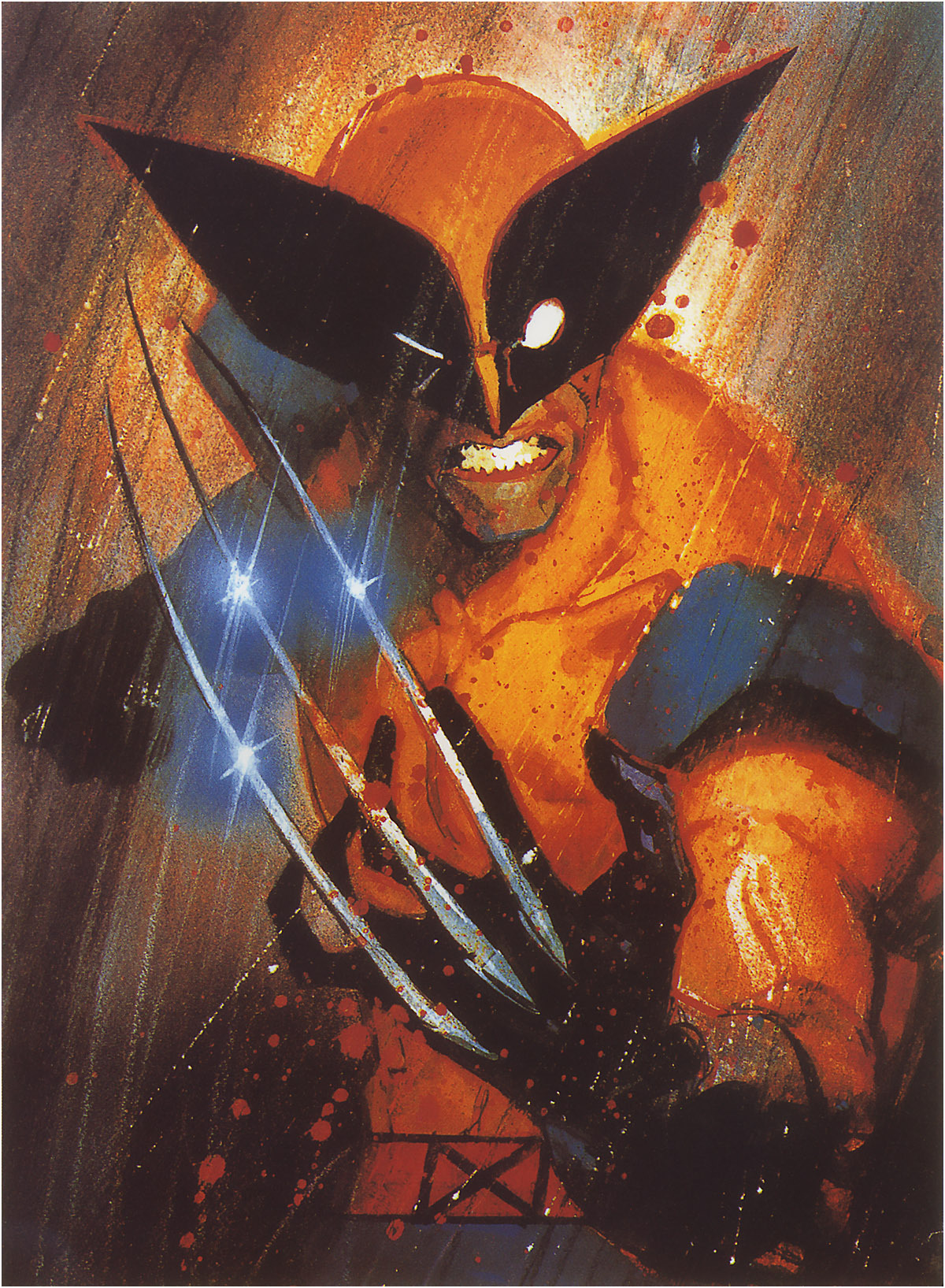

Conversely, Watchmen’s universe contains almost no direct elements of Ketterer’s dystopia, and instead only falls into the category of Greene’s definition of dystopia as preventing independent thought. Instead of creating a directly oppressive and tyrannical government, Moore instead forms a world in which corporations and powerful individuals subtly exert control and manipulate the masses in order to gain power and influence. In Watchmen’s “realistic world, governed by power politics” (Paik 27), the most important elements of control are eerily similar to those of the American present: the media. Thus, thought is controlled by advertising and other media and independent thought is stifled, fulfilling Greene’s definition.

Adrian Veidt, the evil mastermind behind the ultimate destruction of the world of Watchmen in order to create a new world order, controls the entirety of the novel and the world inside of it through media influences. Before Moore reveals that Veidt is at the center of the conspiracy to destroy half of New York in order to unite the world, Veidt’s commercial empire permeates almost every page of the graphic novel. Before the attack on New York, Veidt’s ad campaign for his perfume, Nostalgia, is seen in the background of dozens of panels. It is found over boutiques (Moore 3:7), diners (4: 24), on torn posters on walls (5:18). These nostalgic campaigns reflect back to a time when there were superheroes and no threat of mutually assured nuclear destruction: a utopia. By bombarding the citizens of Watchmen’s world with imagery relating to the past, Veidt controls their thoughts and emotions, forcing them to feel anxious about the threat of the Cold War. After resolving these fears he created in the public through the Nostalgia ad campaign by killing millions of people in New York and ending the Cold War because of a new perceived alien common enemy, Veidt continues to exercise influence over the public through his new “Millennium” campaign, that shows figures facing toward the now bright future(12:31). Veidt even talks about the way that he influences the public through advertisement and media in Chapter 10 on page 8, saying that because of the trends of pre-war times, he is going to invest differently “into the major erotic video companies. That’s short term. Also, we should negotiate controlling shares in selected baby food and maternity goods and manufacturers”(10:8), because of the baby boom he predicts. Veidt’s control is subtle, yet absolute, giving Watchmen the qualities of intellectual control instead of direct oppression as in The Handmaid’s Tale.

Finally, Veidt literally destroys independent thought when he threatens to destroy the world. The superheroes of the novel all agree to follow Veidt’s lead because it is the only way to unite the world, and the deed had already been done (11:27). Yet Rorschach, the one dissenter who wishes to return to America and tell the world that Veidt is behind the destruction is obliterated. Because the rest of the superheroes “must protect Veidt’s new utopia, one more body amongst the foundations makes little difference” (12:24). Rorschach is destroyed because of his refusal to follow what Veidt wants him to believe, and so Veidt continues to exercise influence over thought and independent thinking by literally destroying his enemy and Rorschach’s dissenting opinion. Clearly, Watchmen fits perfectly into Greene’s category of dystopia as being a government that stifles any kind of oppressive thought and serves instead to manipulate thought and control its citizens’ minds.

Not only do The Handmaid’s Tale and Watchmen fulfill two differing definitions of dystopia, but they also represent two different dichotomies between good and evil. The Handmaid’s Tale, which clearly fulfills every feature of Ketterer’s dystopia definition, creates a distinct Manichean dichotomy of good versus evil. Conversely, Watchmen only fulfills Greene’s definition of dystopia, and blurs the lines between good and evil. Though The Handmaid’s Tale contains elements of thought suppression, it is not the most salient dystopian feature of the novel. Instead, Watchmen is distinctly characterized by the repression of independent thinking and in doing so creates a world in which good and evil are on a spectrum and characters and corporations cannot necessarily be placed on one end.

The Handmaid’s Tale grapples with evil in distinct dichotomies that are perceived by not only the reader but also by the citizens of Gilead. This novel’s “Historical Notes” present a perspective from hundreds of years after the Gilead Empire, denouncing the atrocities that were in place at the time. The black and white nature of good and evil is one that is clear because the dystopia was overthrown; it must have been so oppressive and miserable for its citizens because they were controlled by routine, roles, and removal of freedom, that they tried to escape and overthrow the government. The Historical Notes present The Handmaid’s Tale as a true story that was “unearthed on the site of what was once the city of Bangor” (Atwood 301) as “thirty tapes in the collection altogether” (301) having been spoken by the same narrator. Because of this conclusion that the tapes came from someone who escape the Gilead regime, The Handmaid’s Tale’s world is one in which the evil of the Gilead government was overthrown. The novel’s easily identifiable evil characters, such as the Aunts, the Commanders, and some unnamed powers who run the government, create a target that readers are invited to view as evil in nature. Because the novel was told in first person and identifies these characters as evil, readers even further view the women and men forced into their proscribed roles as being good, while those who did the forcing are represented as evil. By fulfilling the necessary components of Ketterer’s dystopia and entrenching herself in the genre, Atwood formulates a world in which the reader’s beliefs about dystopia are reinforced. There is an evil overlord and government who presides over a good citizenry. In order to restore the balance of good over evil, the government must be overthrown. These citizens of the future are able to claim that, “Gileadean society was under a good deal of pressure, demographic and otherwise, and was subject to factors from which we ourselves are happily more free” (302), because of the overthrow of this evil government, further imposing strict categorizations of good and evil.

Watchmen, on the other hand, presents a much grayer view of good and evil, particularly in the form of Adrian Veidt. Veidt reaches the height of his control over the world when he chooses to employ dystopian means in order to attempt to create a utopia. Sending an ‘alien’ monster he created through genetic engineering to New York, Veidt causes a cataclysmic neurological disaster, killing millions, with the intention of uniting the world against a common enemy. Moore places the destruction of Times Square on six full pages at the beginning of Chapter 12, ensuring that the reader must take in the entirety of the carnage. Placed amongst the the bodies, Moore places discarded newspapers that read “WAR?” in large typeface (Moore 12:3-6), indicating that the society was on the brink of destruction before this terrorist event, along with a discarded pamphlet for The Veidt Training Method. This pamphlet falls to the ground amongst the destruction, reading “I Will Give You Bodies Beyond Your Wildest Imaginings” (12:6). This darkly almost comical insertion of Veidt’s presence into the scene demonstrates not only his responsibility for the event, but also signifies that perhaps Veidt could truly have meant two things in what he was communicating; he wanted to help the people of the world by literally helping them to perfect their bodies, yet gives the world dead bodies in order to unite them. Though he has murdered countless people, “we are invited to read this extended scene of death and destruction as the signifiers for the near-miraculous founding of a new and peaceful order, a golden age of international cooperation and solidarity” (Paik 35). Instead of viewing Veidt as an inherently evil character, the reader is asked to instead see that perhaps his evil actions serve a higher and ‘good’ purpose.

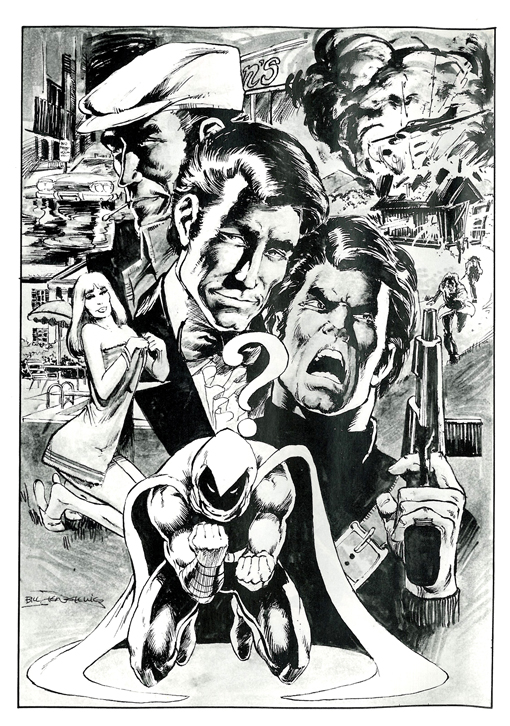

Moore confuses the question of good and evil further through his characters Rorschach, who represents an idea of justice and the vindication of good and evil, and The Comedian, who seems amoral but in fact sometimes stands for good. After the heroes find out that Veidt has committed this attack, they almost universally agree to cover up his involvement for the betterment of society. Yet Rorschach disagrees, and leaves to return to America because “evil must be punished” (Moore 12:22). As seen earlier in this examination, however, Doctor Manhattan chooses to kill a crying Rorschach instead of allowing him to reveal what Rorschach believes is Veidt’s evil nature. Though in this moment Rorschach represents good, he is imprisoned as a violent criminal earlier in the novel. Similarly, the Comedian is evil in his love of senseless violence, yet says that “Somebody has to save the world” (2:10), even though this perhaps inspired Veidt’s evil deeds. The Comedian is even killed because he uncovers and opposes Veidt’s plot: “He knew my plan would succeed, though its scale terrified him” (11:25). The Comedian is seen murdering his pregnant Vietnamese girlfriend (2:14), yet in some situations clearly takes a moral standpoint. These two characters muddy the waters between good and evil and cause the reader to seriously question the morality of not only the world of Watchmen, but of dystopias and powerful governments as a whole.

Finally, though Veidt commits an evil action of mass murder, he is perhaps good in his attempts to create a true utopia resulting from a common enemy, but Moore complicates this issue further with the final frames of the novel. On page 32 of Chapter 12, a lowly assistant at a newspaper is seen reaching for Rorschach’s journal that reveals every part of Veidt’s plan, as the symbol of the Comedian’s badge lies on his shirt. Though the story ends here, there is an epigraph on the last page, on which is written “Who watches the watchmen?” (12:33). Here, the reader sees that only two confusingly amoral at times and moral at times characters, Rorschach and the Comedian, are the watchers of the world. They selectively condemn evil, and in others moments perpetrate evil, yet they are both silenced because they condemn Veidt’s actions despite the moral gray area they reside in. Their ideas of certain acts as being concretely good or concretely evil demonstrate just how confused the notions of good and evil are in Watchmen. By stifling their voices, Moore indicates that Greene’s definition of a dystopia is one that creates a more realistic world, in which there is never a true dominance of good over evil in the end.

Through their varying uses of dystopia and dystopian features, Atwood and Moore bring to light a hidden feature of each type of dystopia. In fulfilling each of Ketterer’s strict features of dystopia, Atwood reveals that this definition of dystopia creates a world with strict separation between good and evil. In only fulfilling Greene’s definition of dystopia as destroying independent thought, Moore reveals that these sorts of dystopias, that are much less extreme in their manifestations, create a world in which good and evil are not clearly defined. By calling morality into question or creating a hyper-strict definition of good versus evil, Moore and Atwood grapple with questions of the nature of power in dystopia, and challenge readers to question their understandings of this genre. Power is not always inherently evil, and neither is dystopia.

Works Cited

Beauchamp, Gorman. “The Politics of The Handmaid’s Tale.” The Midwest Quarterly 51.1 (2009): 11–25. Print.

Greene, Vivien. “Utopia/Dystopia.” American Art 25.2 (2011): 2–7. JSTOR. Web.

Ketterer, David. “Margaret Atwood’s ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’: A Contextual Dystopia (‘La Servante écarlate’ de Margaret Atwood: Une Dystopie Contextuelle).” Science Fiction Studies 16.2 (1989): 209–217. Print.

Paik, Peter. “Utopia Achieved: The Case of Watchmen.” From Utopia to Apocalypse: Science Fiction and the Politics of Catastrophe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. 23–69. Print.