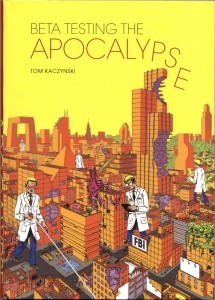

I first encountered Tom Kaczynski’s work while delving into the substantial collection of comics-related materials in Columbia University’s Butler Library stacks, where there is a run of Fantagraphics’ anthology title MOME. I very much liked Kaczynski’s deliberately drawn short stories such as “100,000 Miles” and then, when I was lucky enough to get a story of my own in the final issue of MOME (#22)—and having an certain amount of thespian training—I greatly admired his piece “Music for Neanderthals”, an account of an actor who takes his method a bit too far to go completely native. His work often gives the impression that it spans the entire history of the planet, which reminds me a little of another Polish-American I worked with, the late David Wojnarowicz. I definitely feel sympatico with Tom’s use of the potentials of the comics medium to go beyond entertainment and impart information of a philosophical nature, which is not to say that his stories aren’t entertaining, but that they touch on deeper issues as well. He began Uncivilized Books to publish first his own and others’ minicomics and now it produces critically acclaimed hardcover collections by luminaries of alternative comics such as Gabrielle Bell and Jon Lewis. So, at the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival last year I approached Tom at his table and a year later, he published my comic book Post York. Now Fantagraphics has released a collection of his short stories, Beta Testing for the Apocalypse. For HU, I talked with Tom via email.

________________________________________________________________________

CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE

________________________________________________________________________

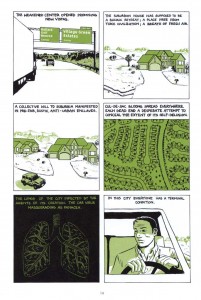

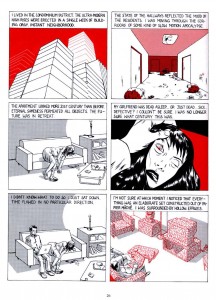

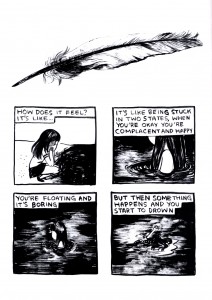

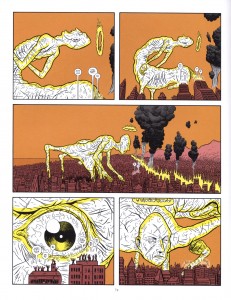

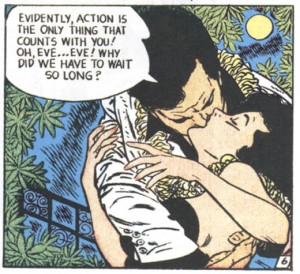

James: You use a single color besides black in the stories, often to great effect. To my eyes, the limited color in your work has a strange feeling, removed from the ostensibly similar use of a single color in a lot of alternative comics, a trend that I think was initiated by Daniel Clowes, Seth and David Mazzucchelli et al. In other words, it is not just for indicating lighting or to hark to old book illustrations. Instead, your single color use at its best is really intrinsic to the storytelling…the color holds or overlays add depth to some images or highlight specific parts of a given drawing to draw attention to something that is going on in the image. Outstanding examples are seen in “100,000 Miles”, “10,000 Years”, “976 Sq. Ft.” and “Million Year Boom”. The color separations can add qualities of delicacy of articulation, or of diagramming, or extradimensional elements. The colors you chose in different stories have varying levels of emotional impact as well. Now, I have to note that in a few of the stories, like for example “Phase Transition” or “Music for Neanderthals”, the color seems to only add lighting, it is almost an afterthought or it isn’t as intrinsic. But in most of the stories, for instance in “The New,” it is absolutely part of how the story is constructed—–and that story may be the most advanced use of the technique, besides being your most ambitious piece to date. Can you articulate why using two colors might sit your purposes more than doing full color artwork, or leaving it in black and white?

Tom: I tend to use color as a storytelling device where in certain instances I can focus-in on certain object or characters. I feel I’m still struggling with color in general. Overall I can cite 3 primary ways I use color in the book.

1. Color as a naturalistic element (as lighting, depth, etc.)

2. Color as pure design element.

3. Color as information.

The three sometimes mix in a single panel, sometimes they don’t. “The New” and “Million Year Boom” are the only two stories that were conceived (and published) with color from the get go and as such work the best for me in that respect. That said, it was fun to go back-in and re-imagine the stories with an added color. Now that I’ve seen the results, I would probably push it a little further next time I have a chance to do that.

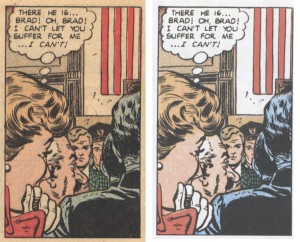

James: I note some variations in the stories in Beta Testing the Apocalypse from the way they were originally presented. In the collection, the story “100,00 Miles” has a green overlay that is considerably lighter in shade than the more olive color it is run in in MOME 7.

The stories “Phase Transition” from MOME 10 and “Music for Neanderthals” from MOME 22 did not have a color in their original printings. In Beta Testing the first page of “Phase Transition” is still black and white, perhaps because it is part of a signature that has pink pages. I see that the olive color goes over zipatone in the other three pages and that the toning is slightly different in the Beta Testing version—on page 4 panel 6 you mottled the tone. I wonder if the color is imposed on some of the stories to unify them for this package, or if, as you suggest in your interview in MOME 10, the lack of color in some stories was a result of not having enough time to do a color separation for them?

Tom: The MOME stories were always vaguely conceived as two-color pieces. But because I often handed in art at the last possible minute ([MOME editor] Eric Reynolds can attest to that!), there was often no time left to think about the color in any meaningful way. I generally focused on having the stories work as black & white pieces (with gray tones) and if there was time, I would add color information. The color changed on the MOME 7 story because the original green wasn’t quite what I wanted. I changed it to the color I originally envisioned, but didn’t get right the first time around. The first page of “Phase Transition” is indeed b&w, partly because it falls on the pink signature (as opposed to the yellow one), but I found that it worked storytelling-wise. The color doesn’t come in until the 2nd page of that story and gradually takes over more of the strip.

James: One of your self-published pamphlets is in full color—-do you think you might do an entire book in full color at some point?

Tom: Maybe… I found full-color very time consuming. I may find a good use for it in the future. I don’t want to rule it out. In the near term I don’t have any specific plans on doing any full color comics.

James: From the example shown in the interview that Gary Groth did with you in MOME 10, the strips from The Drama magazine look to be of a similar level of quality as the work here, along similar lines of subject matter and are also 2-color jobs. Is there a reason why you didn’t include them?

Tom: I didn’t think those strips would’ve worked in the book. They were done at least a year before the 1st MOME story, and they are much more ‘gag’ strips. There are some ‘gag’ strips in the collection (the four 1 page stories from MOME 12) but they work with the larger themes of the book.

James: I also see in that interview that you acknowledge J.G. Ballard as an influence, even if Gary didn’t do any follow up questions about him. I noticed the influence immediately in reading your work.

Tom: Yeah, Ballard is pretty big for me. His earlier books like The Drowned World, Crash, High Rise and The Day of Creation were huge for me. I love a lot of his short stories; “The Ultimate City” may be my favorite. I’ve also come to love his later, post-Empire of The Sun (one of the few I HAVEN’T read) work like Super Cannes and his last novel Kingdom Come.

James: There are the obvious correspondences in “100,000 Miles” to Crash, but some of your others like “Million Year Boom” and “976 Sq. Ft.” remind me in particular of a few of his perhaps less-known works such as High Rise and Concrete Island. Both of those books depict protagonists who become subsumed in the constructs of a society that in supposedly advancing has actually broken down, that has taken on the quality of an intolerable new “normalcy”. Is it perhaps that, like Ballard, in transitioning between disparate societies at an early age, you have a unique perspective and are able to remove yourself and see where you are in an overview of sorts, or to see around the corners, so to speak?

Tom: I definitely think that the experience of emigration gives you a different perspective on the idea of society. When you are born into one world (Communist Poland), and then are transplanted into another (USA), and then witness the utter transformation of the first (collapse of USSR & the Eastern Bloc), the idea that society can radically be changed (for better or worse) is not that far fetched. That is one reason that the US (a country of immigrants) has been such a successful and dynamic society. The recent political/economic climate in the US feels like an attempt to freeze and define the US as a specific unchanging idea. History is catching up with us, the US is no longer a ‘young’ undefined country. Even many European countries (not to mention countries in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and South America) have political & economic structures that are more malleable, that may better cope with future challenges (I got away from Ballard here… but it seemed in the end the question was less about Ballard but about ‘society’).

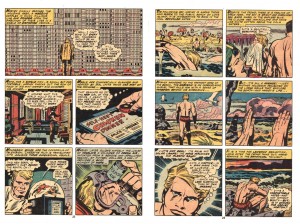

James: I just read another interview with you that Kent Worcester did, where you cited a specific Jack Kirby image from his 2001 comic, a panel of a man walking up to a building that is just a huge wall of windows—it freaked me out because that is one of my favorites of Kirby’s and it is part of a passage that I had actually thought of mentioning to you! The Earth Jack depicts is so polluted and crowded, a world where pure air can only be breathed out of bottles that one must purchase as we do water, an existence so dehumanized that the protagonist feels he must join the space program, to escape in order to realize any sort of life for himself.

Your work gives me a similar feeling, as if you are dealing with expressing what it is like to live in a world that has gone beyond the point of no return, but with no escape possible, as if all we can do is construct semblances of sanity for ourselves, that work within the insane structures that we must fit into.

Tom: I love that Kirby image! I believe that was from 2001 #5? I agree with what you’re saying here. One of my favorite J.G. Ballard stories is “Billenium” about an overcrowded world where everyone basically lives on top of everyone else. The protagonists in that story find a hidden room and all that new space is an almost unimaginable luxury. They proceed to share the new space with some friends and family until it fills up and becomes indistinguishable from the rest of the world. We need to find these spaces (whether real or imagined) and inhabit them; to create germs of possible and impossible new worlds… hopefully better ones. There’s a danger in that. Things could get worse… but sometimes not doing anything at all, is worst of all. One thing I hesitate doing in my stories is to destroy the world. If “Billenium” was an Italo Calvino story, that room could be a germ of a new city; an invisible city growing in the midst of the old one… and eventually it would grow to replace it. I think we need a better imagination, one that goes beyond wishing for the apocalypse.

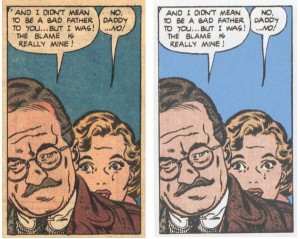

James: I appreciate the format of Beta Testing and the way you have manifested your work so far, because I personally have always preferred to work on short stories, at least partially because of the labor intensive nature of comics—-I like to work on things where I have the opportunity for more variety—for instance, it can get very awkward trying not to be repetitive in the angles and compositions when one is drawing the same characters and backgrounds for many pages.

The last story in Beta Testing, “The New”, is the longest and probably the most ambitious story I have seen you do so far. Do you prefer to work on short pieces or are you working your way towards longer stories?

Tom: I really like the short story (in comics and in fiction) and it’s something I’d like to keep doing in the future. There is something satisfying about a good short comics story. There are more opportunities for a tighter structure… it’s easier to get that certain density of narrative. Dan Clowes’ shorts from Eightball (post-Like A Velvet Glove Cast in Iron), the ones that ran concurrently with the serialized Ghost World, are the pinnacle of the form for me. “Blue Italian Shit”, “Caricature”, “Immortal Invisible”…they all have tight structures, a satisfying density of narrative. They’re just perfect comics. That said…

James: Can you see yourself writing and drawing an entire graphic novel eventually?

Tom: I’m often frustrated I can’t get all my ideas into a short piece… In fact I almost always wish my stories had a few more pages to develop this or that germ of an idea. So, I’d like to do longer comics at some point. My upcoming book TransTerra is probably the closest thing to a novel-length narrative, but that was still constructed episodically. I don’t mind repetition so much. I think it works well in comics… whether it’s a 4 panel gag, or 300 page GN. It’s almost necessary to set up a kind of visual/narrative rhythm. It was nice to be able to stretch a bit in “The New” and not have every page be crammed with information. After doing a bunch of short pieces in a row, I’ve been yearning for a bit more space…like the character in that story “Billenium”!

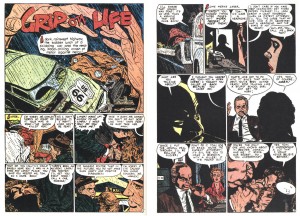

James: I’ve never seen an index that alphabetically listed every sound effect in a comic before. And Ballard’s entry leads to a highway sign in a panel for “Ballard Golf Heaven”, and I liked how the table of contents is figured on a greater timeline, but isn’t much help in locating the stories. Such details play with the new climate in comics where we should try to accommodate future scholarship, by ensuring that page numbers are included, etc.—-you certainly left a lot of room for examining this thing through different “lenses”….we’ve come a long way!

Tom: Ha! Well, it’s something I’ve always wanted to do with comics. Indices, notes, and glossaries are some of my favorite things in books and I didn’t want my book to be left out! This all comes out of lots of conversations I’ve had with cartoonists and writers over the last few years. In the end I wanted the index to be another story in the book. One that comments and explicates the other stories. Some entries are in there for fun. Like the sound effects, or cars. Others alert the reader to concepts or phrases that have been quoted, mutated or just plain stolen. One thing that is often left out of comics criticism are the images. They are often examined in terms of plot or composition, but rarely do writers get into the complex visual references that often show up in comics. One of my favorites pieces of writing on comics is a Ken Parille piece on Clowes’ David Boring that excavated the connections to Hitchcock’s Vertigo among many other things. I hope in some future edition, the book can be published with an index. Other cartoonists have played with this kind of material. Kevin Huizenga comes to mind with fake indices & glossaries. In fact I was just working with Kevin (& Dan Zettwoch) on the index to their next book, Amazing Facts & Beyond. It’s amazing and goes way beyond my index! In fact they called it the beyondex! Maybe we can start a trend! Index wars!

The idea for the table of contents come about organically. A lot of my stories were titled after some kind of measure… “100,000 Miles”, “976 sq. ft.”, “10,000 Years”, etc. when time came I wanted to create a unifying design & organizing principle. Also, I saw all these stories taking place in the same world… in my mind for example, “The Cozy Apocalypse” is a prequel to “976 sq. ft.” In his famous book, SMLXL, architect Rem Koolhaas begins the book with a multipage series of charts that detailed his life: time spent flying, swimming, eating, etc. over a period of a few years. In some ways my chart is much more immodest, spanning from the big bang into the far future and covering vast distances.

James: You wrote and laid out a story that Dash Shaw finished in MOME #17. You also collaborated to some degree with me on Post York—we came up with the cover together; and then at one point you suggested that I delete a few panels on the page with the initial ending and leave white space. I wasn’t sure, but I thought on it for a while—and then I decided to take that idea a lot further. I ended up jettisoning multiple panels on nearly every page that didn’t seem needed and those omissions greatly expedited the storytelling and improved the design of the book. It was great for me to be able to break away from the way that DC, for instance, works, where every inch of what they call the “real estate” of the page must be filled. How do you feel about collaborating with other artists, and do you think you might do more in the future?

Tom: I would love to collaborate more! Too many cartoonists are antisocial! I understand the need to sit alone in a room in absolute focus and work on something. But we’re social creatures and being able to collaborate with someone who’s on the same wavelength is very satisfying. It was really eye-opening to see Dash execute one of my stories. His approach is just so different from mine. I’d love to draw someone else’s story.

James: Your first few full hardcover books have gotten a very encouraging response; Gabrielle’s book was picked as a book of the year by Publisher’s Weekly and both her The Voyeurs and Jon Lewis’ True Swamp were reviewed favorably in PW and elsewhere. Is this resulting in an influx of people wanting to work with you?

Tom: I’m grateful I was able to work with amazing cartoonists almost out of the gate. I’ve admired Gabrielle’s & Jon’s work for a long time (and your work too!) and being able to publish them is an honor. I’ve definitely had an influx of submissions and I have a hard time staying on top of them. At the same time, Uncivilized Books is still a very tiny company and I can’t publish everyone. That also means I have to be very picky and reject projects that I really like. I’m still trying to find my specific publishing groove. I just finished figuring out my third season of books and I think I am maybe getting closer.

James: I know that besides doing your comics, you teach. Do you find that the publishing takes even more time away from your already full schedule, or how do you deal with that issue? I mean, I asked this of Sammy Harkham as well; one can get quite involved in promoting other people’s careers and have to fight to find time to do one’s own work. Particularly when one is young, one is developing in leaps and bounds and so one needs to direct one’s energies carefully.

Tom: This year I had to put teaching on the back burner. I still mentor some students and attend critiques and seminars, but I’m not teaching a full class this year. There just isn’t enough time. My own comics tend to be more esoteric and have made me very little money… So, I’ve always had to have some other job to support my cartooning. I’ve never had the luxury of just focusing on my comics, and I’ve always had to claw back time from other endeavors to create my comics. I pretty much assume I have to do something else… if my comics ever make enough money, I may have to re-evaluate my use of time, but for now I try do projects that are interesting. Uncivilized Books has been very rewarding. I’ve learned so much already and I know there’s a ton of learning left in the future.

James: Can you give a rundown of the upcoming projects for Uncivilized Books?

Tom: This is the next season of books:

Incidents in the Night by David B. and translated by Brian and Sarah Evenson.

Amazing Facts and Beyond by Kevin Huizenga and Dan Zettwoch

Sammy The Mouse Book 2 by Zak Sally

Over the Wall by Peter Wartman

James: Will you continue to produce minicomics and “floppy comics” such as the one I did for you?

Tom: I want to! I really see mini-comics as my research & development department. I can work with artists on a smaller scale trying out formats and media like flexi-discs [Post York includes a flexi-disc by my son Crosby–JR] that may be more difficult to do in larger quantities. I wish there was a better distribution network for these formats. I think they are vital formats that I hope will live on.

James: How do you see comics developing in the future? I am encouraged to see people like Joe Sacco using comics for journalistic purposes, or you using them to what I would call philosophical ends.

Tom: I certainly hope comics will embrace a variety of genres and formats. I listened to an interview with Gary Groth (disclosure: he’s our publisher) recently (on BoingBoing) and he said that the boom of comics in the wider book market was a strange thing. He said that most people read comics, not because they are ‘comics’ but only because they deal with some subject matter they’re interested in (like Maus by Spiegelman, or Palestine by Sacco, etc.). They’re not interested in comics ‘as comics.’ I think he’s right, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. We need those people! We need the reader who is interested in a subject, and chooses to read about it in comics form. They may not be interested in them ‘as comics’ but some of them will grow into that ideal reader… especially if there are many good comics on lots of different subjects. I think the same could be said for books, movies and other media. Most people want something very specific from movies: a blockbuster spectacle, something funny, gory, or emotionally engaging. But only a minority is interested in film ‘as film.’ There’s just a lot more of them because there are more movie goers overall. Books…literature in general is an ancient art form that has gone through many of its own crises and mutations over millennia. Comics as such have been around for only a fraction of that time. Comics emerged from an ephemeral medium. All those floppy comics were not supposed to be kept and written about. Comics in service of something other than commercial entertainment have been around for even less time! It’s going to take sometime to develop and find an audience that appreciates them for what they are. We’ve made great strides over the last decade and a half. We need to be patient and keep producing better and better work. I’m pretty hopeful.

_________________________________________________________