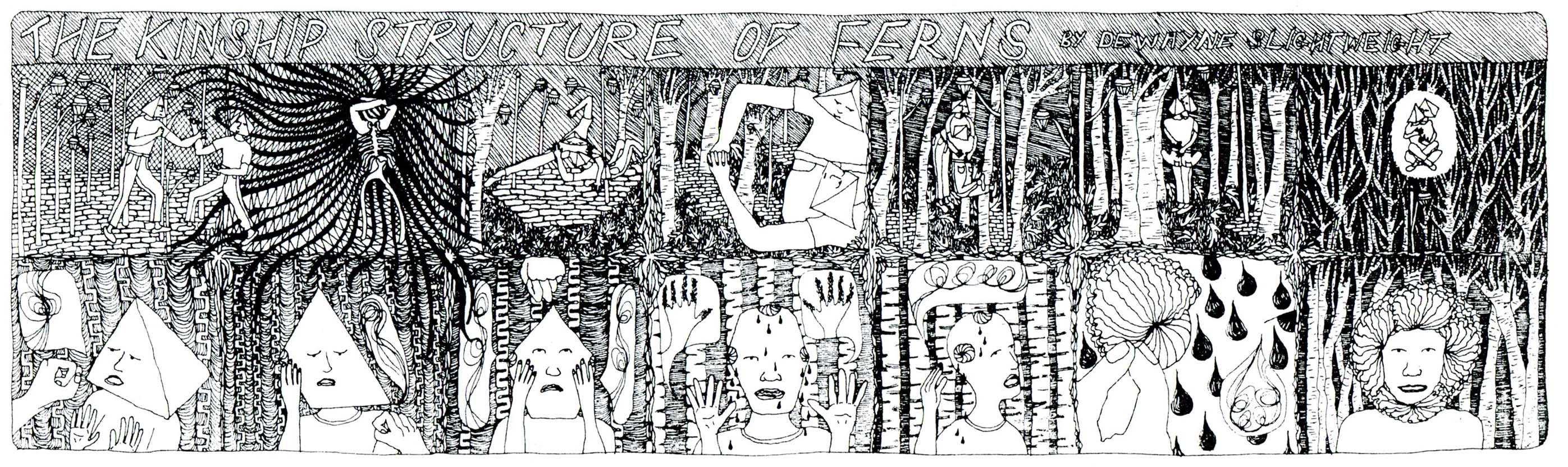

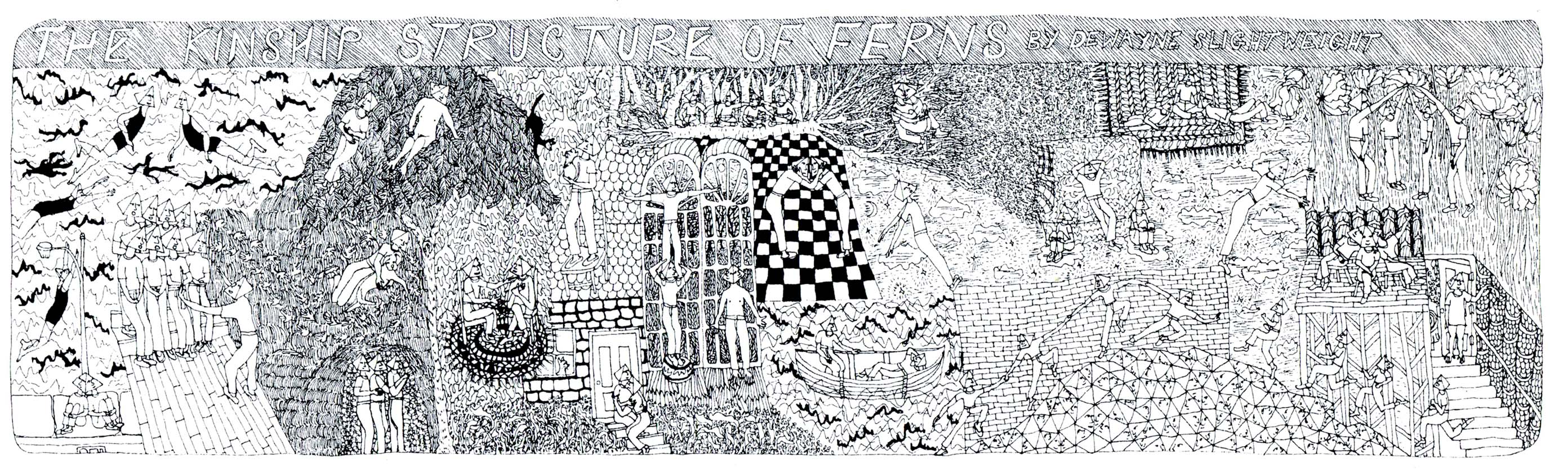

This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007 . A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

_______

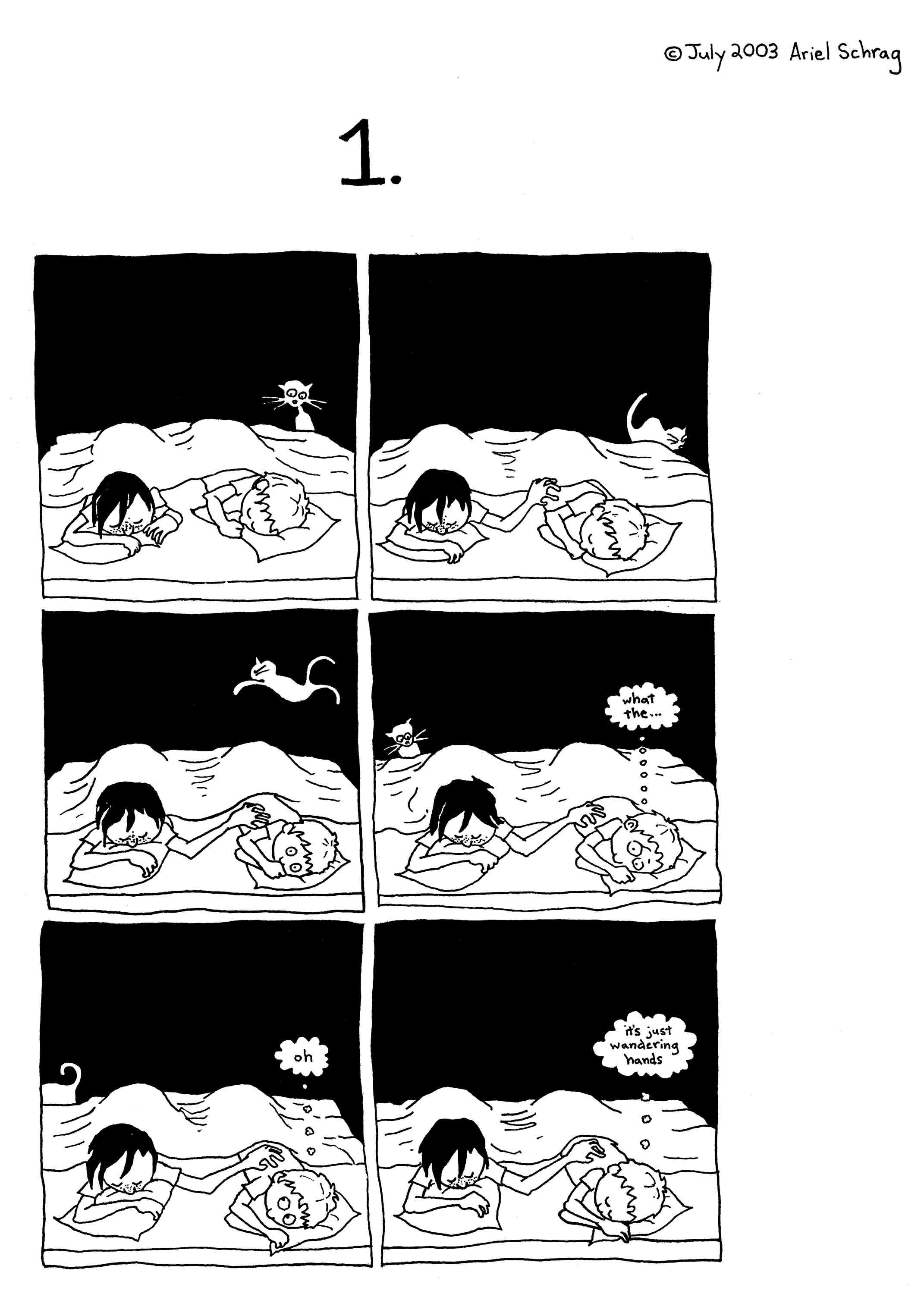

Blessed are they who have wives, as though they had them not.

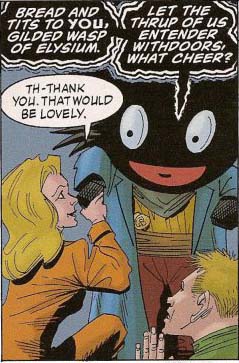

I had my most memorable argument over the worldview of the new aesthetic left after seeing the movie adaptation of Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta with a good lesbian friend, who was a better friend than I to the orthodox conception of “the gay utopia.” I was fairly repulsed by this cardboard morality play, in no way thickened by the sub-cardboard acting of Natalie Portman. In this pathetic tale, a loquacious clown-faced humanist “revolutionary,” who is supposedly lent some kind of soul by — what else? — his appreciation of Billie Holiday, magically overthrows the corrupt police-state overlords in a largely bloodless (not to mention classless and raceless) revolution. As the reader may infer, I was rabidly contemptuous, and felt that Billie Holiday’s grave deserved no more desecrations. My companion, whose intelligence I did not and do not impugn, was resentful of the wet blanket with which I spoiled the warmth she had felt from viewing a movie with such an upbeat and morally agreeable conclusion (certainly a rare event in Hollywood). Aside from the likelihood of such a remarkable series of events as those depicted, I wanted to know what the results would be of this groundswell of goodwill. What system were they ushering in? Who would take power? Where would the money flow? Never mind picking up the trash or fixing the streets, what the hell WAS this revolution? For who and by who and to result in what? She wasn’t interested in answering. But I think one reason I succeeded in being so thoroughly irritating that evening was that I was perceived as badmouthing the dewy-eyed hope for liberation, power source of the gay utopia.

What does V for Vendetta have to do with the gay utopia? For one thing, its flaccid message of tolerance has its most tolerable moment when Natalie Portman’s character is in prison being tortured, and is given strength by reading the letters of a lesbian former prisoner. However, when it turned out that this whole prison scene had been some kind of growth-experience fabricated by V, our anarchist Paliacci, I completely lost any sympathy for his nebulous agenda. That’s just me. But the nebulous nature of the program, parsed on the movie poster as “Freedom! Forever!” is, I believe, a key to why this shitty film, and many another campy ode to personal rebirth through social adversity, is unassailable to followers of the new politics of sentiment. Struggle is to be transparently a romance. The humanism of our era has but one virtue, truth, and thus only one true romance, authenticity. But even this truth is viewed from outside, and thus becomes contingent, like the transparent naiveté of cinematic empowerment (cf. Dirty Dancing, and many another nostalgic slumming-liberation romance). To me, Natalie Portman’s character being duped by the radical ethos-bearer into revolutionary loyalty through manipulation of her deepest terrors and desires was not just a deal-breaker, but inevitable. To my friend, who saw the big picture, I believe it was a metaphor for the traumatic journey of self-knowledge required of all seekers after justice, the individual contributing to the great collective uplifting/leveling of humankind. Again, no wonder Billie Holiday sings their anthem.

I had opportunity for pause the next day when watching the gallery for a show my inner-city high-school art students had created in response to the displacement of public-housing residents (I lay that bare in order to establish my progressive cred). The local erudite fascist wacko, who comes to every event at this solidly left-leaning art space in order to beat do-gooders about the temples with quotes from Wyndham Lewis, returned to engage me in an uncomfortably long discussion of how the coming environmental Armageddon would require every man to cleave to his family and affirm his race loyalty. I adhered to my position that race was obviously a consideration in the allocation of misfortune worldwide, but if the bell tolled for anyone, it tolled for whitey. Strangely, his story lacked the shining poetry of Goebbels, just as my friend’s response to the movie lacked the analytical acumen of Hannah Arendt. When he finally left to go attend to his weirdo fascist diet, I washed my face and hands vigorously, and tried to figure out what I was supposed to glean from two such opposed yet parallel experiences of perverse alienation. The conclusion I’ve now reached is that my friend’s shimmering fairy-tale has the certainty of eventual success. My eugenicist nemesis is possibly dangerous, especially if he gets hired by Fox News, but his attempt at post-Nazi policy proscription is ultimately irrelevant.

But nothing could have seemed more irrelevant in the early 19th century than the ideas of Charles Fourier. Though he was hardly the first post-Renaissance visionary of planning, his is the name I associate more than anyone with the concept of “utopia,” an engineered paradise in the here and now. Like Jeremy Bentham, he was an ardent feminist and utilitarian. He was, of course, a socialist, an early adherent of the concept Marx and Engels would come to name “the labor theory of value,” but a socialist who despised government, an early anarcho-syndicalist of sorts. He also believed in a vast array of familial and coital configurations. And that planets were bisexual and carried on some kind of intergalactic erotic communication. As a mystic of humanism, applying to society the anthrocentrism of hermeticist philosopher Giordano Bruno, Fourier more than anyone may have envisioned our cultural evolution as a rational-magic techno-pantheistic totality. Society is composed of freely-chosen collectives (“phalanxes”) of freely self-constituted monads. This is the legacy of the charismatic Left, but where can it be found in today’s world-weary world of cynical realpolitik?

It can be found everywhere. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad doesn’t have any homosexuals in his country, and so our expansionist pro-life President would seek to send our military, in which gays are certainly represented in a generous proportion, to violently overthrow this un-gay utopia and give its women the right to vote for an American shill. My contention is that the gay utopia is already here — except that sexuality has turned out to be a cage rather than a key. Regardless, barring a global bloodletting, the Middle East is yet another frontier for the humanist assault of the West, in which the boundaries of abjection, on which the patriarchal walls of our civilization were erected, are doomed to corrode. Ahmadinejad can be in denial about homosexuality, but he cannot ignore the rhetoric of human rights. All he can do is lie and dodge accusations. He is incapable of answering directly to the power which cannot be acknowledged. His magically pure Iran is no match for the magically post-pure fantasy of the gay utopia. Faith will be crushed by identity.

Inevitability is a hallmark of the landmark theoretical utopia of modernity, Marxism. A strong utopia is not a romance. It is a statement about history. Lockean democracy is a utopia — it promised freedom for all, and delivered it to the professional middle classes of the industrialized world, while pushing its refuse to the margins, Slavoj Zizek’s un-flushable Real. The fluidity of capital has outmaneuvered any consciousness-raising among the proletariat, quickly finding new markets for suffering. But the limit of these markets is that, sooner or later, all that’s left are the things that cannot be property, and cannot be liquidated. Ironically, water is a prime example. At that point, the giant disparities in global resource access will manifest a verdict on Marx’s prophecies. Humanism, the basis of the gay utopia, has its Real as well. That ineradicable underbelly of the desire to liquidate boundaries of identity is the persistence of hierarchies. This is why it matters who is in charge of the gay utopia — who takes power without being acknowledged. If it’s academia and the global entertainment industry, then the power has been consolidated. The revolution is constantly being televised.

Paraphrasing Julia Kristeva, the existence of the boundaries of purity are what keeps sacrificial violence at bay. It’s easy for me to see holy war as the result of the Western attack on purity, just as Christian and Muslim fundamentaists would have it. I think that, in response, there is a need to elaborate the gay utopia much more completely, but in art and magic, its true voice, rather than theory, for which it has no use — V for Vendetta being the case in point. Kristeva quotes the rabid anti-Semite Celine, who rails against the technocracy thusly, “There is an idea that can lead nations. There is a law. It stems from an idea that can rise toward absolute mysticism, that rises still without fear or program.” The universal abjection of gender indeterminacy, purified by a new ideal of immanent boundless love, needs to be raised to the transcendent state it deserves.

Sexuality, on the other hand, is something I’ve barely touched on, because it is time to shake it off as a talking point. In fact, as the V for Vendetta anecdote illustrates, ideology far more than proclivity is really the point. For now, in this society, gay people need to be free of harassment and assault, and visibility is necessary. There is a need in the long term, however, to diminish sexual habits as a primary public signifier, much like the social importance of one’s race or income. Race distinctions will continue to diminish. Income differences, and attendant credit gambles, on the other hand, eventually may cause cataclysmic upheaval, but art can’t do much about that. The vast straight majority doesn’t need to embrace homosexuals; they need to stop monitoring sexual behavior. The fear of continuity, of lost individuality, is tied to gender, and a new romance of gender must emerge.

Quoting gender-essentialist feminist Helene Cixous: “One can no more speak of ‘woman’ than of ‘man’ without being trapped within an ideological theater where the proliferation of representations, images, reflections,… invalidate in advance any conceptualization.” For this reason, the morbid pedantry of much art about gender/sexuality does not point in a promising direction, no more so than the failed abstract jouissance of androgynous modernity that the pedantic art aimed at reforming. My version of a gay utopia is a gendered communitarianism, in which gender manifests in flesh and art, not subordinated to sexuality and the Deleuzian striving, after Artaud, for a “body without organs.” Lots of “body artists” I like create work that is admired for its undeniable power, but marginalized insofar as that power is gendered, and thus provides an obstacle for polite humanist discussion.

I’ve just about reached my limit of patience with male artists who more or less share my upbringing. Most of us seem to have nothing more on our minds than regurgitating the comic-book narcissism of our youth and mobilizing our raging insecurities against the alleged “politically correct” conspiracy against our once-proud cultural standing, or donning the signifiers of fashionable androgyny, and using their theory bookshelf as their dildo-bludgeon. I am part of this historically highly privileged group, and, while our fantasies of persecution and sensitive genius are disabling and unseemly, I would argue that rabid masculinity has a place in art. Just as feminist art has been hamstrung by negative, fearful work, shrilly extolling an insular platform, the face of serious art about maleness has been twisted into a permanent sneer of ironic defensiveness or a permanent grimace of pedantic clenched-ass sincerity.

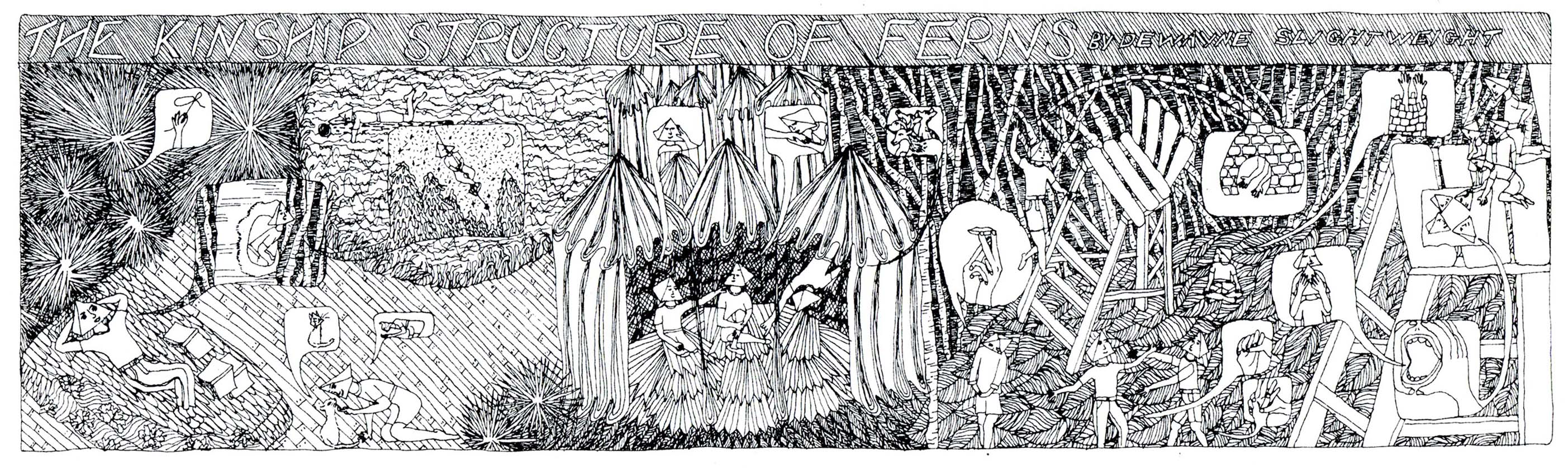

Chicago artist Paul Nudd is most certainly a member of my demographic. His drawings, collages, sculptures, and videos share a signature style, a design sensibility clearly informed by the 1980s thrasher aesthetic of Zorlac and Santa Cruz skateboards, abstractly but directly referencing viscera, bacteria, orifices, and wounds, nebulous cartoons signifiers of abjection. I’ve always been a fan of this work, but never more so than when I saw him speak at the Vonzweck space this August. Nudd shared his homemade mead, and the small crowd, entirely white and including only one woman, was certainly on his side. I was not inclined to judge him harshly, but my fraternal admiration was balanced somewhat against some uneasiness I’ve been feeling towards the group shows he’s been associated with of late, shows that feature mostly rather bitter, frustrated white-guy work. But my best suspicions were met by a presentation that did anything but massage his reputation or preach to the choir.

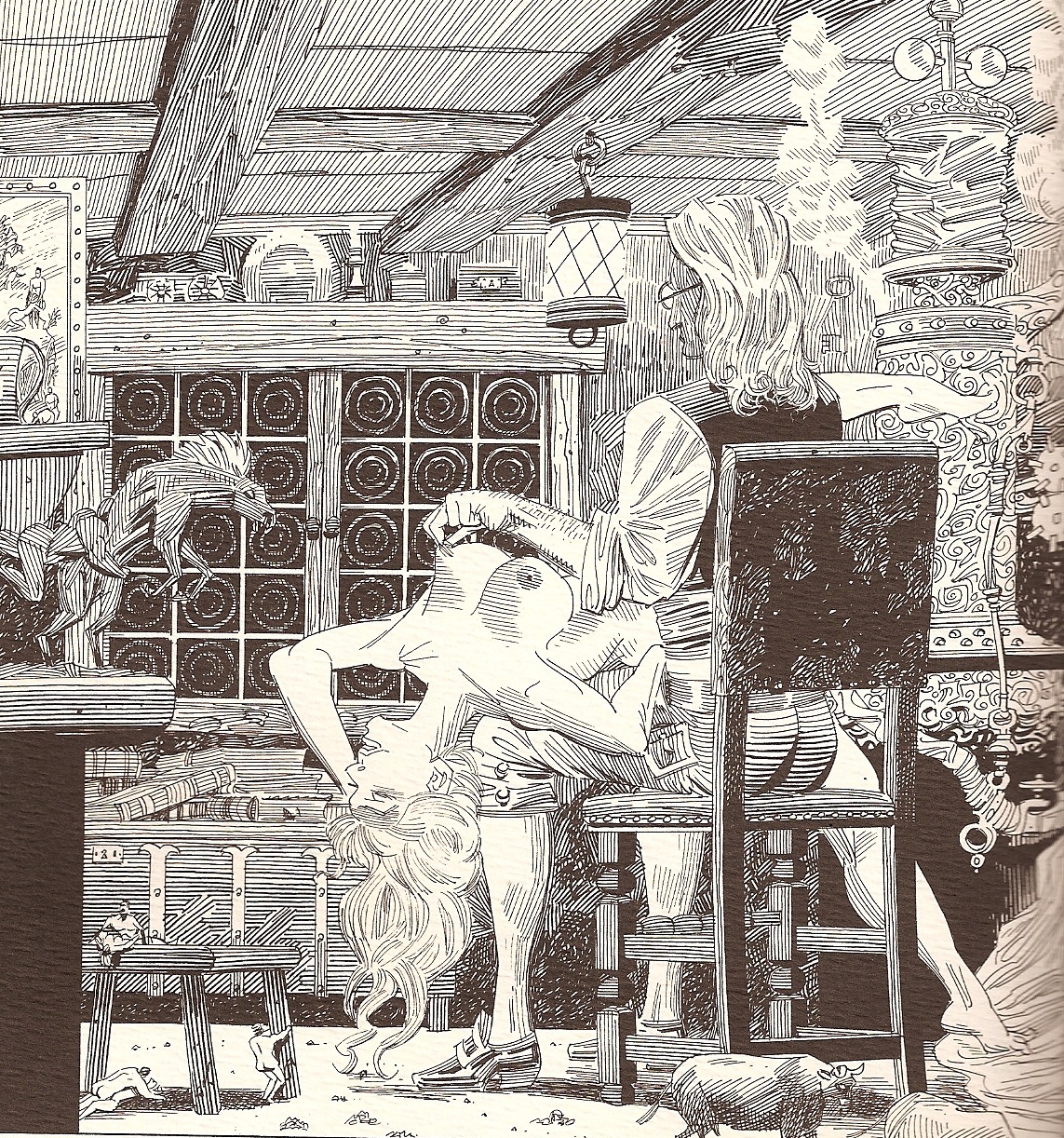

The mood was set by turning off lights in order to run the slide projector, which was eventually only briefly employed. It ended up that the only source of light, along with one slide that ended up dwelling on the wall for a time, came from Paul’s latest video of fluids silently surging in and out of a palpitating opening. The dominant color was red, which gave the proceeding an impression of flickering firelight. Nudd is currently collaborating with another local shock-jock artist, Patrick W. Welch (not in attendance at the lecture), who is best known for his works and shows around the idea of the “Micromentalist Manifesto.” Paul gave out photocopies of some of their collaborative drawings, intricate tableaux of vivisectionist pornography and general Armageddon. Paul spent the first 45 minutes or so of his presentation praising Walsh’s drawing skills and joyfully relating largely self-deprecating anecdotes of their collaboration. After this he passed out more free artwork, a photocopied booklet of drawings with a silkscreened cover, and reluctantly went through some of his slides, which, blown up from their modest scale, only emphasized his delicate, gracefully articulated linework, and his subtle palette. He was eager to answer my questions about influences from female biomorphic artists such as Lee Bontecou and Inka Essenhigh, and he moved on to passing out a series he had done of covers of books he loves, and gleefully read aloud from grossout passages, stopping frequently to make sure he wasn’t upsetting anyone.

Like the most exciting and inspiring “gay utopia” performances I’ve experienced, this lecture had a thick sense of atmosphere, a heady delectation of the body, and communal generosity. What separated this talk from matching up with the gay utopia “look” was the fashion aesthetic (metal band shirts instead of thrifted blouses and tank tops), a cosmetic distinction, and, more importantly, the lack of any affirmational bacchanalian exhortations. Now, while I have greater admiration of queer hippie fashion than of thirtysomething dudes in black, and I appreciate the hippies’ exultation in magic, much of the utopian fantasy rings so hollow (lacking hallucinogens, or at least fantastic music). The part of Paul’s presentation I found preferable to the latter-day Happenings I’ve attended is a sense of quiet, and laughter not weighed down with pretensions of Dionysian sensuality. And beatification found through a healthy dose of repulsion, rather than a program of forced cosmic optimism.

Echoing the insights of my heroes Georges Bataille and Julia Kristeva, I want to emphasize that such repulsion is essential to transcendence (now more than ever), and there’s no lack of it in the work of strong gay and female artists. Photographer Cindy Sherman comes to mind as one of Paul’s favorites, but an artist I could not help but think of during the presentation I described is the gay Canadian artist Daniel Barrow. Barrow creates small, precious multiples, such as trading cards and balsa-wood airplanes, but his best-known work are his performances in which he “puppets” his drawings on a transparency projector, to the accompaniment of a recorded spoken narrative. A fan of the bemused world-weariness of Quentin Crisp, Barrow’s apocryphal stories of gay celebrities feature sickly children, magical animals, and a decidedly perverse fixation on the body — i.e., more than a little tainted with disgust and outright horror — all illustrated in romantic brushstrokes and rococo pastels.

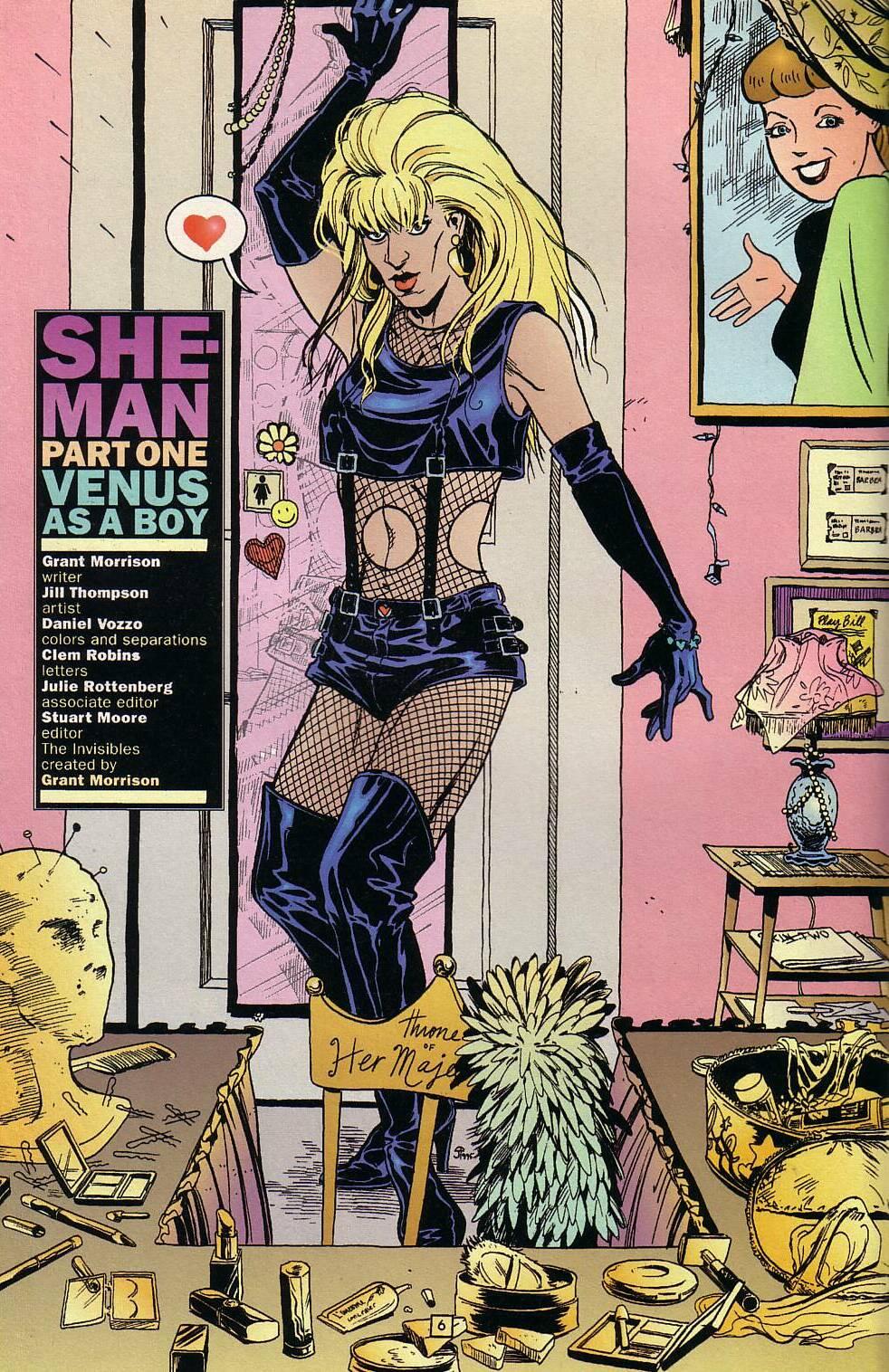

The darkened room, the evocation of boundaries of pure and impure, the highly male fear and fascination with (Mother’s) exposed innards… Barrow and Nudd have so much more in common than, in my opinion, do Nudd and the attractive but mean-spirited work of John Currin, or do Barrow and the equally lovely orgiastic porn assemblages of Scott Treleaven. The wonderfully wanky psychedelic collages of Fort Thunder, Lightning Bolt, and other Providence products, however, strike me as pretty heterosexual, and yet are visually consonant with much aesthetic output of the pegpants noise-rock freak-folk kids of the early ‘Oughts, LTTR and/or otherwise. And I maintain that the magic of Animal Collective’s music comes from the scent of Wicker Man and Charles Mansen, the hint of sacrifice, moonlight murder, the protean anarchy preceding the legalism of Leviticus. Which, if it wasn’t repulsive, would have far less appeal.

On the topic of symbolism outside the phallic Law, Carolee Schneeman and Louise Bourgeois are two of the more prominent artists to have taken up the representational torch for the re-ascendence of matriarchy in the capitalist era. Multiplying bodies and their organs with a horrible joy, a simple inversion of the male joyful horror described above, Bourgeois’ mutant sculptures and Schneeman’s visceral performances claim a new kind of female power, a “phallus” of sorts, but a female phallus, formless, interior, and possessed of numerous eyes. Even more than in the work of Paul Nudd and Daniel Barrow, who also swim in shadow through a hallucinogenic sea of (inevitably) gendered bodies, vision for these women, and the artists who follow them, is occluded and questioned. Whether it’s Schneeman writhing in processed meat with kinetic umbrellas, or Bourgeois’ pillars of breasts, their emphasis on intuitive and haptic responses jar the visual supremacy of the Renaissance tradition, and the humanist grid does not burst into flowers of rational tolerance, but rather begins to creak and buckle down its own universal anus-eye in the absence of any faith to hold knowledge together.

Two thinkers that have contributed a great deal to my perhaps equally unstable worldview are a pair that would hardly have many kind things to say to one another, but controversial thinkers on gender who illustrate strong archetypes of the old male order and the new female order, both equally relevant in making sense of the post-humanist future. C.S. Lewis, vilified by liberals for Christian children’s stories opposing Islamic imperialism (Ahmadinejad anyone, again?), wrote profoundly in essays as well as fables on the structure of the natural order, as he saw it. In The Problem of Pain he opines that genders are not realized in individuals, but are metaphysical ideals subsisting throughout Creation. Gender is far more a matter of power than genitalia, and all of humankind is feminine in comparison to the grandeur of God — in this significant sense, all humans are women. Gender is found in an interior space, the place where a Christian faces his Maker. Essential gender difference is foundational as well to the revolutionary feminist writer Shulamith Firestone, who would end the nuclear family, end compulsory education for adolescents, and end pregnancy as we know it, turning reproduction over to technology and ushering in an era beyond rigid boundaries, in which women once again take control of society. Given the situation in which the world finds itself, it seems unlikely that all will fit the “feminine” stereotype of nurturance and inclusion. But, in an era of want and upheaval, it is appropriate that our trust be given to women (not masked jackasses a la V for Vendetta). Even if supporting Hillary does seem a bit too cynical for my taste at the moment.

Belief in gender power rather than atomistic “mere tolerance” is a direction that I wish to see pursued in art, and a direction that the “gay utopians’” magical stunts could aim at. That is, if performed in humility before divinity rather than affirmation among equals. Colonial appropriation of indigenous practices, the secular mysticism of phenomenology, are no replacement for the absolute amazement and anguish we must feel at the bodies we inhabit and the world we have destroyed. Contingency and democracy are realities of our daily life, and necessities of our group situation. But they are a poor replacement for the awe we must feel before a greater power, the Big Other outside of our reality, that has made it possible and worthwhile to work and love, though never to the point of even beginning to fulfill the infinity of desire.

So, if the gay utopia isn’t really about being gay, what about being gay? John Boswell, who wrote about the history of tolerance for homosexuals in medieval Catholic Europe — quite widespread before the 12th century — makes a number of strong points in defining the problem of what gayness or homosexuality is and how hard it is to locate in history. On one hand, there are sources that suggest that gay sex in highly tolerant societies (like classical Greek and Roman cities) is engaged in openly by a large proportion of the populace, whereas intolerant societies (like Persia in the Crusades or Iran today) proclaim no homosexuality whatsoever. This goes along with the conclusions of Freud and Kinsey (separately) that the split between heterosexuality and homosexuality is a highly questionable one. Of course, neither term existed before the bastard Greek-Latin term “homosexuality” was coined by Havelock Ellis at the end of the 19th century. Many people who have had homosexual feelings or experiences do not acknowledge themselves to be gay (such self-affirmation is still significantly tied to class status). Many people are attracted less to genitalia and more to eye color, curly hair, feet, humiliation, etc. Gay utopian scholar, artist, and activist Gregg Bordowitz phrases it evocatively: “all sexuality is queer sexuality.” Which is easily confused with the homophobic shibboleth about homosexuality being a choice. It is, in a sense — if hetrosexuality is a choice too. Sex is a vast array of thoughts, words, and deeds; desire is a shadowy cave; sexuality is an assumed identity, a lifestyle. Many people who are sexually repressed have severe problems both causing it and resulting from it — ditto for many people who are oversexed.

Managing one’s identity is a way of navigating between desire and sex. Sexuality relates a person to a social order. A gay person signals by their identity that they relate to a social order of diversity, cosmopolitan values, political rather than familial affiliations — a worldview that does, in fact, resemble a great deal of contemporary First World social milieux, and the forward-looking politics of globalism and hybridity. But being “straight,” heterosexual, as normative as it is, is clearly defined in relation to its supplement, homosexuality. Socially, (though not for persecuted individuals) heterosexuality is an identity just as fraught with anxiety — anxiety, as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick explains, about being gay. A straight person often uses their sexuality as a way to hide any number of flaws in their normality. In post-industrial societies, the institutions of heterosexuality (like marriage) evoke a bygone era: the rural past, when kinship affiliations were key to the survival of the wider group. Just like the straight person who uses “normality” as a mask, the culture uses nostalgia as an ideological front– in part, to cover up the non-rural present, the regime of individual control that Foucault famously termed “biopower,” a society where, despite the humanist dogma of personal liberty, everyone’s private habits are in fact a matter of public scrutiny — and individual self-hatred.

Sexuality is a modern necessity. It is involved with policing the murky infinity of desire within, and confronting the infinite policing of behavior without, but nonetheless, it is something we construct. Gender is often confused with sexuality — they are both concepts tangled up in discussions of modern identity. But I would argue that sexuality is the part that is presented, both to oneself and the world, for approval. Gender (not genitalia) is how our minds and bodies fit in with everything we perceive. Gender is the stable power that generates all instability. Hovering indeterminately between two eternal poles, our gendered mind experiences sexual desire, but this is a result of our gender, not the cause of it.

The perception of gender as a ramshackle hodgepodge of hegemonic proscriptions is the thin philosophical gruel served up by the legacy of cultural studies. Because intelligent American academics like Judith Butler, Elizabeth Grosz, and Donna Harraway borrowed from eloquent French thnkers like Georges Bataille, Jacques Lacan, Julia Kristeva, and Michel Foucault, and talented French writers like Jacques Derrida, Francois Lyotard, and Gilles Deleuze, feminists and queer theorists have followed the pull of gravity, moving further and further from explicit politics and into a stale rhetoric of endless dynamistic analysis and personal exploration, buying up blurry platitudes and hoping for cred at the margins of banality. A famine, a technological innovation, an orgasm, are all intriguing crises, equivalent affirmations of flux. Though these writers have articulated important points, they are seriously hampered by their inability to theorize their unacknowledged utopian aspirations, and thus their ideological location. The ideas of queerness that underlie the gay utopia resonate with such a stochastic worldview, as do the ravenousness of capital, the force of the feminine, and the amorphous violence of sexual desire generally. These certainly cannot all be the same thing. Or can they?

There are reasons that this shapeless political-poetic cluster applies with equivalent intuitive resonance to gender, sexuality, and economics. It is the case that technology mediates law and flesh, tending toward the specialization of tasks and replacing bodily strength, seemingly obviating the barrier between manual work (for men) and biological work (for women), as Shulamith Firestone proposes. Openly gay men are effeminate if only by definition — traitors to the masculinity they admire and reflect. But, precisely owing to the fear of betraying the fragile brotherhood, masculinity is an ill-fitting jockstrap for everyone. On the other hand, despite mulleted caricatures, lesbians lack this anxiety, and thus do not resemble men in the way that gay-appearing men resemble women. Slippery female sexuality detaches the phallus and multiplies the vulva.

The indigestible remainder of capitalism is hierarchy, the deepening of divisions in the erasure of differences, speculative liberty moved by the compressing force of its own iron limit. Hierarchy is not unique to capitalism, but it is synonymous with capital of all kinds. Monosexual situations often result in expressions of sexual violence to create order — schools and military organizations come to mind; conversely, Kristeva points out the way in which strict hierarchy in Indian society reduces emphasis on sexual and gender taboos. Desire cathected as dominance is a basic expression of power, from rape to the scintillating Freudian analysis of Woodrow Wilson’s spiteful and pedantic Messianic delusions.

Which brings up my preoccupation with the way in which Christianity and power are misunderstood, both liturgically and historically. Christianity is filthy with responsibility for many things, including some portion of transmuting classical humanism into our current “culture of life.” But we can see now that, through constantly agonizing over its history, the religion remains outside of its consequences, like the body which is eternal and the body which disintegrates. Transmuting, recall, is alchemy, a neo-Platonist animism, a non-Christian form of magic. Rather, thanks to Saint Paul, Christianity is not an experimental method, but a mystical resolution of cosmic impossibility — including the contradictions within Judaism that once alienated him. John Boswell avers that Paul, a central founder of the Church, did not condemn homosexuality, but rather child molestation, and excessive gratification generally. Elaine Pagels and others argue that the “pseudo-Pauline” passages marginalizing women were added later. Paul advocated a missionary approach that was humble and heartfelt, not a “cloak for greed.” His approach adopted the rhetorical approach of the Greeks in the service of revolt and revelation, not to subjugate populations in the service of power.

Despite their often honest intentions, perhaps the only significant favor American Christians have done the world, though it is quite significant, is not to free the hearts of men, but to secure the place of faith as an alternative to an instrumental materialistic worldview. Paul advocated the restraint of celibacy to inflame faith, prevent unwanted children, and protect the body, not to encourage the bigotry and repression of affect that Christianity is now known for. The emotional condition among Americans is not hope, faith that our lone trickle of love can fill the expanding endlessness of Creation — though this sounds a lot like the gay utopia — it is rage, resignation, anxiety, and despair in the face of unfilled “fulfillment.” Mannerisms adopted to intimidate, bluff, and seduce our comrades have the studied insincerity of a smile in a sickroom. This abject submission to unreason we see in advertising, in Hollywood, in Broadway, is too easily incorporated into queer irony.

Christianity strove to replace cold, abstract classical values (the forerunner of our progressive rationalized city), and the ancestry-bound, corporeal insularity of Judaism (conservative by the standards of any era) with an inward-looking practice that dwells forever just on the edge of infinite love, the border between humankind and everything we are not, unitary particularity and ultimate vagueness, the body with numerous organs.

The only boundary of humanist philosophy is the shadow the philosopher casts on his work, a shadow constantly swatted at ineffectually by subsequent philosophers, popping up like spring-loaded gophers in the grid of interchangeable positions. But boundary in religion is foundational. In Christianity we have not a marginal shadow but a central body, the crucified Christ, blood that becomes wine, meat that becomes bread, wounds that become windows on the infinite. Sacrifice and cannibalism are not reintroduced by Christ, but transubstantiated into an effort at mutual restoration. Miraculously the limp body of apassive man (the pariah of both pagan and Jewish society) becomes the phallus of the world’s hope. A Moon-Pie can be a blessed sacrament, our conduit between hunger and beasts, emblem of continuity with the world. We eat what we kill, and thus kill what we eat, far more than we copulate. From what we eat we derive energy, heat, shit, tears, and a rotting leftover, the body. “The body” might be a provisional site of intersecting discourses, or whatever, but the body is not. What we share with life we share with our kind the most, and with nobody completely. moving from ultimate newness and organization, ascending through levels of grace, facing the impotence of God in the impossibility of resurrection, and the glory of God in the impossibility of Creation.

Holy S/H/E/IT is the magic that allows us to reflect the many-tentacled thing-object of our unspeakable affections into a universal secret triumph over suffering through suffering, through law to go beyond the law. But this does not mean that Christianity is not crushed by the evil done in its name. Spreading love and peace was a vehicle for genocide and on a scale matched only by our contempt for ourselves. But no doomed private pride can match the grandeur of the Interior Castle. The Kingdom of God, like the gay utopia, is a paradise of orifices — the wounds of the suffering Christ. But unlike humanism, Christianity does not resist criticism through absorbing it and feeding from its energy. Some part of it resists the pale professional conversations in academic cloisters; rather, it exposes itself to the light of the world, and constantly cracks and crumbles into dust through publicly interrogating its aporia, under the weight of the hypocrisy it condemns. Is there any point in even trying to talk about it?

My feeling, however, is that the aim of the postmodern project to somehow correct the excesses of the Enlightenment has noticeably failed. If calculus teaches us anything metaphysical, it’s that change and volatility are far from unquantifiable. Deterritorialization, Deleuze’s concept of the tendency of social forces to multiply and disperse, is nothing new. Unity has had its fragility officially exposed ever since Galileo and Luther publicly flaunted the Church, and Thomas Hobbes was soon and forever after a black sheep of humanism for critiquing both democracy and the scientific method. The gay utopia champions both the autonomous uniqueness and the egalitarian interchangeability of all, and, with millions of people now living in deprivation and peril, it’s not clear what or who has yet to be freed through the rethinking abstractions of the West. I would like a reterritorialization to oppose but also to redirect the many reactionary reterritorializations that promote intolerance and imperialism, rather than merely leaving things to the inevitable ongoing deterritorialization, which continues blithely managing citizens, property, and information through a rhetoric of legalistic ethics and endless evolutionary growth. International law and multi-lateral treaties cannot be expected to yield equality and improvement. Like St. Paul our civilization has lived through the law in order to die to the law. Our culture is a culture of freedom. What remains to guide us?

The art of the body, rather than the theory of the body, has a lot to say about the potential of repulsion, the only curb of desire. Thresholds in monotheism exist to sustain purity and resist sacrificial violence. Such thresholds must be preserved, and this provides art with a small but meaningful role in the world. Violence against gays, women, and racial minorities are not wrong because they supersede the autonomous self-policing of Deleuze’s desiring machines, but because violence is wrong. Spreading our products, litter, and worldview to every corner of the world is not wrong because of the sacredness of freedom; it is wrong because we are not living up to our responsibilities to our communities and our nation.

Colonialism is the crisis of our time, as in sci-fi writer Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy. A profoundly eco-aware species that deplored hierarchy includes a facilitating semi-shamanic third gender, known as ooloi. But despite their vast knowledge and capacity for nurturance, this species moved from world to world, sucking its resources dry. The freedom of capital is the freedom of desire, the freedom of a raging destructive conflagration. It can be deflected through voluntary boundaries. We must find a way to create a peaceful fortress. We cannot let the fluids of power flow without restriction in and out of our country. Christianity makes it possible to love our neighbor in isolation from her. National sovereignty, not individual fulfillment, is the only hope for the great mass of people.

Body art reminds us that we have physical boundaries that leak, just like the boundaries between sacred and profane. Transgressing these boundaries is a religious act, or a sin. Imperfection is universal, and not everything in nature is ours to touch, but art can touch it — this can be seen in the colonoscopy videos of Mona Hatoum, or in Annette Messager’s crocheted sweaters on taxidermied birds. These works are viewed in shadow because twilight dissolves boundaries. Twilight is therefore both holy and evil. The strong response I feel to art like this reminds me that the place of art is, in some sense if not literally, outside of the everyday world. This is why the magic of the gay utopia is so inspiring, but also so deceptive. A utopia is not a place for people to live. It is a place to look through a dark hole and imagine. Which might be, in a good sense, kind of gay.