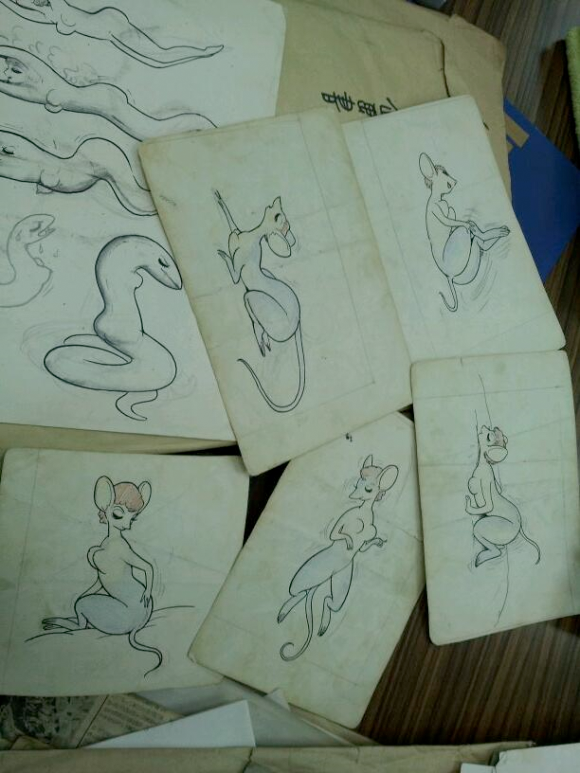

Last week, all my twitterers were a’fluttering with the good news. Rocket News 24 translated into English and passed along some tweets from Rumiko Tezuka, who had uncovered some treats from her father’s long-under-lock-and-key desk drawer. The extant bits the tittering author found especially amusing were a small stack of erotic drawings of an anthropomorphic mouse with an accompanying image of a woman transforming into a serpent-like creature. The drawings themselves are lovely. Miss mouse is depicted playfully sort of rolling around an impression of a bed or soft surface. Her downcast eyelashes don’t acknowledge the presence of a viewer. She smiles with an unselfconscious sensual comfort that seems to affect the article’s author with no small amount of unease.

Miss Mouse

There’s some gibberish about “base urges” and a hypothetical about sensations in Walt Disney’s backside; musings on the “social propriety” that restricts how Uncle Walt was supposed to react to such sensations. What says such social propriety of how closely we are supposed to think about the sensations of the backsides of long-dead men? Reading further, such a propriety calls for projecting this effluviate notion in the direction of a grown woman:

“We realize these things are more accepted as just another form of expressing your talents in families of great artists, but should our kids ever stumble across one of our old skin rags, we hope they handle the discovery with a little more discretion than Rumiko.”

A propriety that demands, in the wiggle-room between an erotic subject and a clear and present exploitative gaze, that one be inserted.

“Don’t worry, though, it’s not like all the pictures are focused on her voluminous mouse breasts. / (in a following caption) See? A few call attention to her shapely rodent derriere, instead!”

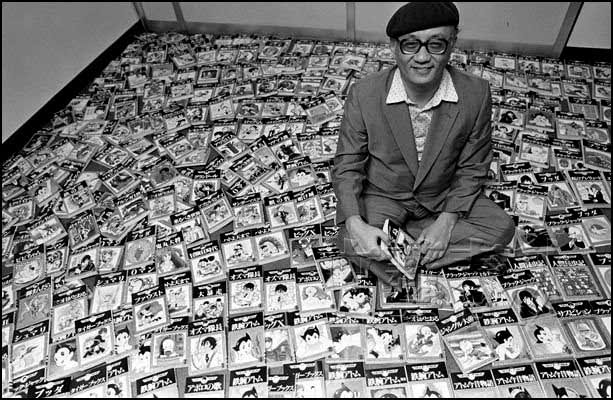

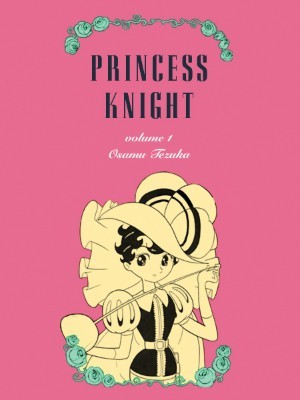

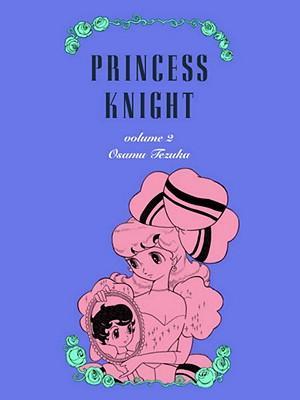

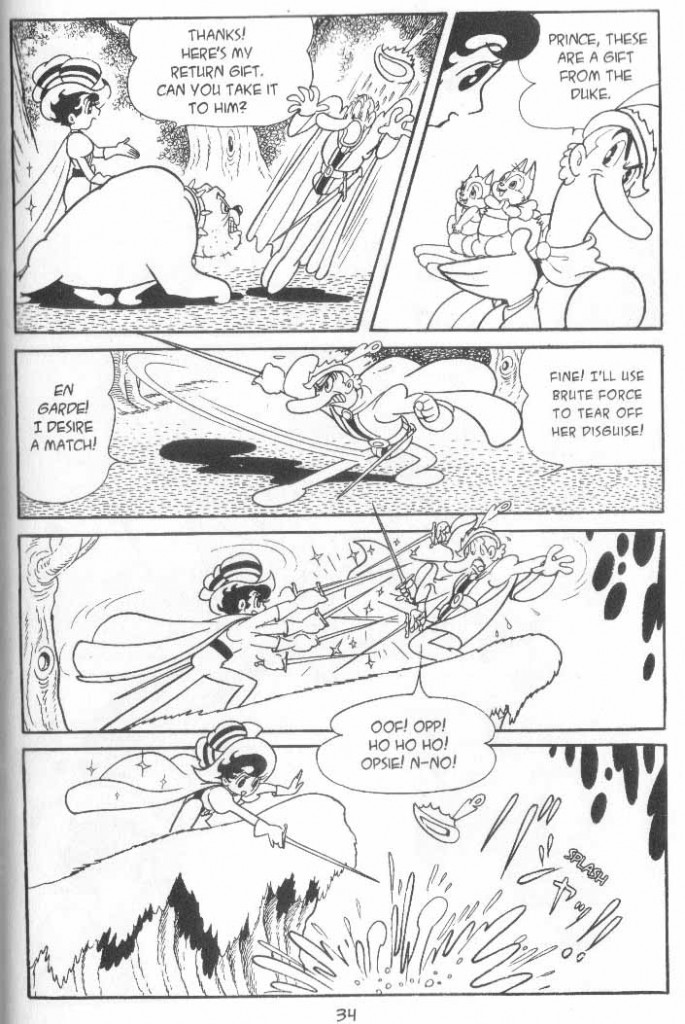

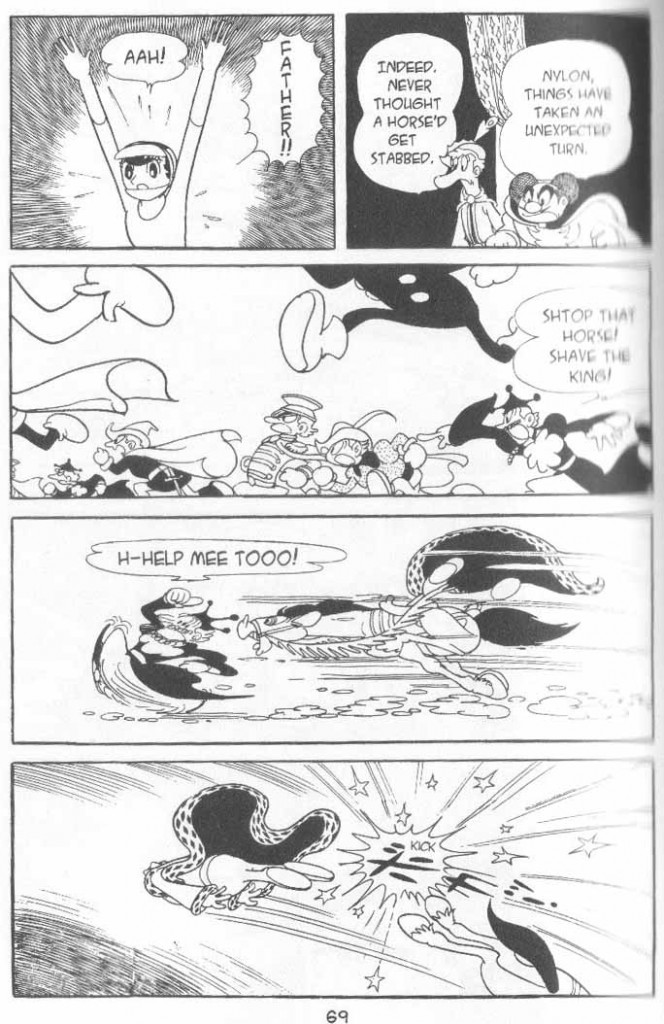

It’s noted that Osama Tezuka is Manga no Kami-sama, the God of Manga, comparable to the Greek patriarch Zeus. Acknowledged is the fact that a butt doesn’t care under which circumstances it would like to be scratched, but not that gods of the Greek variety have similar concern for the manners of mortal men. Astro Boy, by some metrics Osama Tezuka’s most popular work, is held up a iconic in exclusion of damned near everything else he created. The reverence of a god through the lens of this one property diminishes the big-heartedness and open-mindedness of Tezuka’s material, some of which is not for kids at all no not one little bit, yet is still the reason creators and fans carry admiration and respect for Tezuka and his work decades after his death.

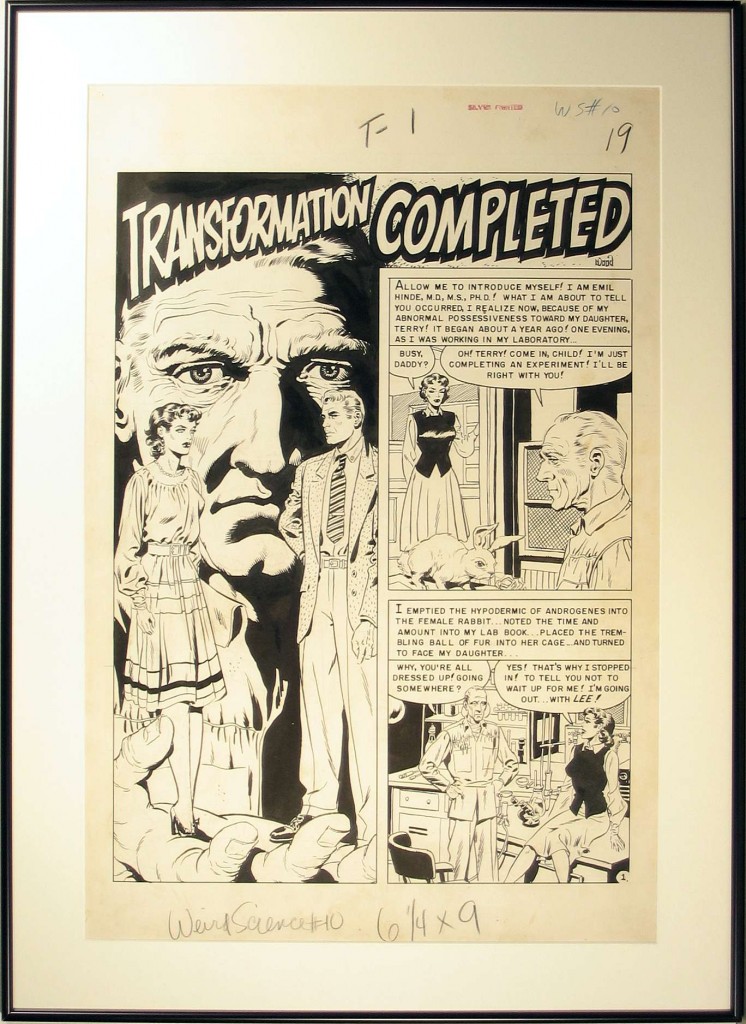

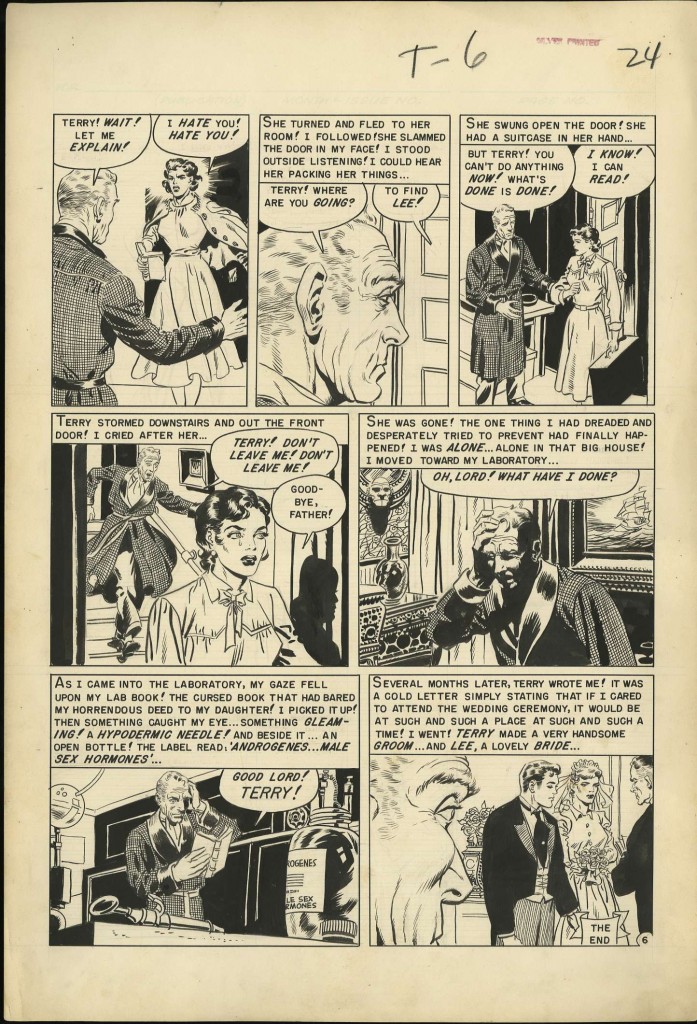

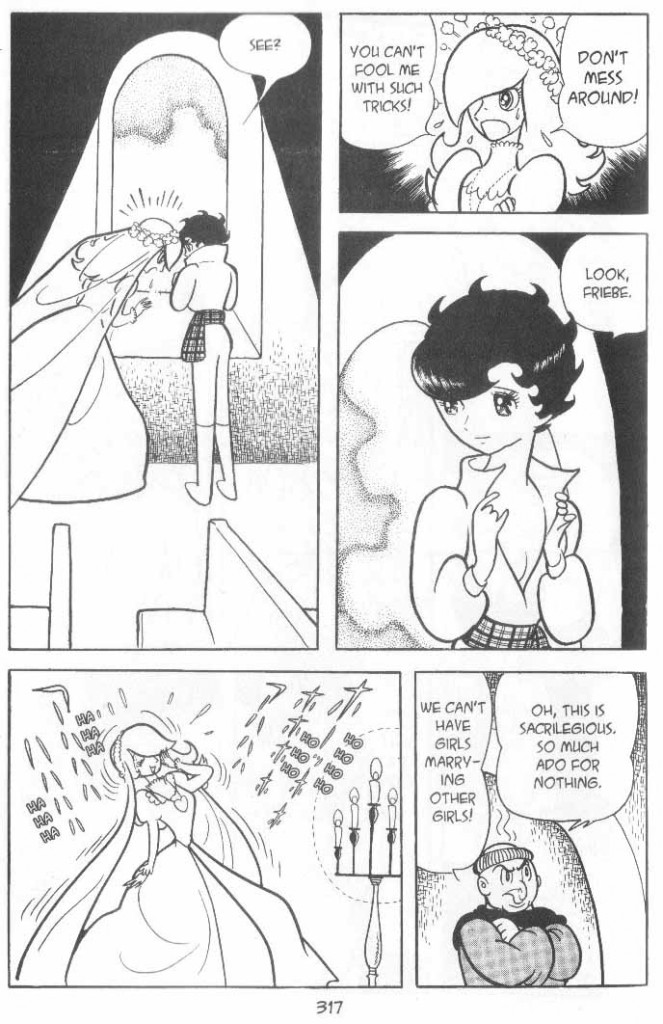

“Tezuka is a furry!” Furries are tittering, too. It’s not necessarily a discovery to furries who have read Ode to Kirihito, Tezuka’s epic medical thriller about a disease that twists human bodies into dog-like forms and their mistreatment at the hands of those who see them as no longer human, or Kimba, the White Lion, his clairvoyant Lion King fan-fiction. Bagi, the Monster of Mighty Nature, featuring the sensual genetically altered half-woman-half-cat is clearer still. There’s little doubting the “furry-ness” of this magnificently lurid series of transformation sequences (transformation is a well-established furry fascination/fetish today). While he lived, Tezuka-sama was a human man, and the concerns of human men (sex sex sex) coursed beneath a great deal of his achievements.

To briefly detour, allow me to bring up Rob Clough wondering about the recently completed final volume of Omaha the Cat Dancer.

“The depiction of the characters’ bodies is so close to human that I’m not sure why this was done as a furry series in the first place, other than being a popular style of the time.”

That’s because furry sensibility goes back way before the furry fandom. Omaha is one of the first widely-read capital “F” Furry comics, rather than a comic featuring furry characters. The sensibility, that anthropomorphism for its own sake, is primary. The other elements of Omaha (explicit sexuality, inclusive diversity, soap-opera pyrotechnics) are special because they are revolutionary in a funny animal comic. Bringing us back home, Chris Randle in a delicious response to the unveiling of Tezuka’s Miss Mouse, provides a lucid answer to Clough’s query.

“If the funny-animals trope has been used throughout cartooning history to simplify, interpolate and transfigure, then lust defines the medium too, even when it was necessarily sublimated beyond the sleaziest outlets.” (“sleaziest outlets” referring to Tijuana Bibles).

Excellently put! Though I must submit that for work with a furry sensibility (animal stories that have an astral resonance to weird little kids who will grow up to be capital “F” Furries), the element of lust is maybe only barely sublimated. We see this in the 1001 Arabian Nights clip, in Disney’s Robin Hood, in this truly obscene Tom and Jerry cartoon from 1943. “Old cartoons are weirdly sexy” maybe isn’t the most prestigious hill of cultural criticism for me to choose to die on, but I’m confident I won’t be alone up there. It’s a subject that apparently must be compartmentalized in this sub-genre for children in a medium for children.

If little prestige comes to Furries from the revelation that the god of manga sometimes worked in the continuum of the furry sensibility, it isn’t my concern. Miss mouse is happy with her own self as she was in that drawer all these years, a set of nice drawings regardless of all our tittering and twittering. Furry to most people is something that gets you, rather than something you get, and Osama Tezuka is continuous in his inspiration to all of us, furry or not, who wish to die slumped over our desks. Various sensations course through the butts of the living, and all the while old Uncle Walt lies naked in his grave, signifying nothing.