Iggy Azalea and Vanilla Ice are both white rappers who were marketed like pop stars while also trying to tell us they were hardcore rappers. They’ve both achieved incredible levels of success only to be hampered by questions of artistic credibility. In Ice’s case, those questions ended his career. In Azalea’s case, I think it’s a real possibility that we may see history repeat itself.

In the past year, Azalea had two singles simultaneously at numbers one and two on Billboards Hot 100, and her debut album, the New Classic, hit number three on the Billboard 200 album chart and number one on the Rap Album chart. She’s also faced a backlash that has repeatedly called her credibility into question. Some of it is certainly understandable: she’s not only the first white woman to hit it big in hip-hop, but also an Australian, compounding her outsider status. One of the biggest questions hanging over her is the very sound of her voice. In interviews, her natural speaking voice doesn’t have a particularly heavy Aussie accent, probably the result of her living in the US for eight years. But it is discernable enough to make her “rap voice” all the more questionable. The harshest criticism is that she isn’t so much rapping as imitating black Americans.

One of the things that always made hip-hop interesting was that rapping was an extension of the spoken word art form, with the idea that one’s “rapping voice” would be consistent with one’s natural speaking voice. It also stands to reason that because rap and hip-hop were linked to poverty-stricken communities, the form’s performers and fans have had little patience for pretense or artifice. White performers like Beastie Boys and Eminem never pretended to be anything more than what they really are: crazy Jewish kids from Brooklyn who were too smart for their own good, and a mixed-up guy from a Detroit trailer park who found both solace and purpose in hip-hop.

On the other hand, even 20 years after Vanilla Ice’s pop career faded out, his true background remains shrouded in confusion. The biography put out by his record company appears to have been different from his actual life story, and there’s no way to know how much was written and released with his knowledge or consent. There are also questions about who actually wrote his biggest hit, “Ice Ice Baby.” Ice compounded the embarrassment when made when he denied that the main sample was taken from Queen and David Bowie’s “Under Pressure.” (For the record, it was, and he did end up having to share songwriting credit with Queen and Bowie, in addition to paying back royalties.)

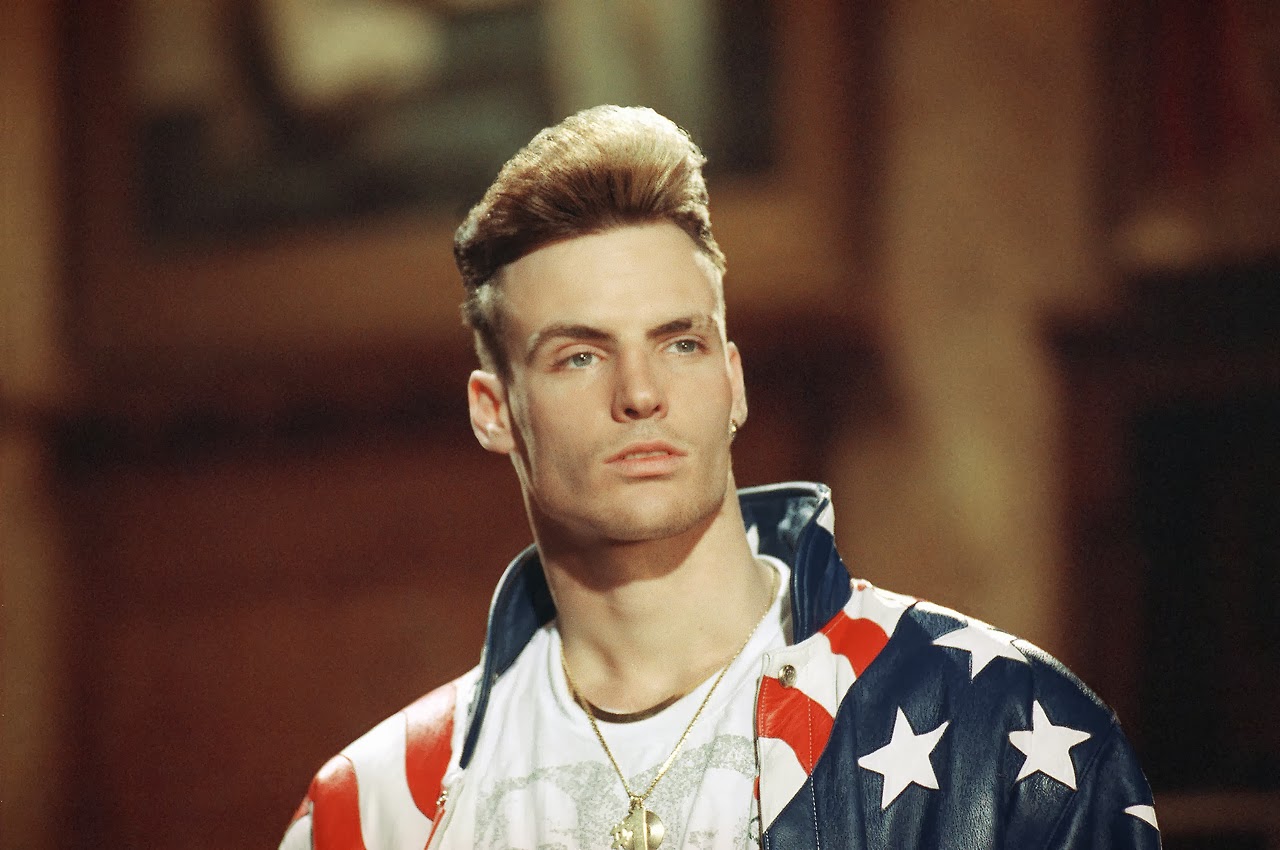

Another problem for Ice was that his own self-image of being a hardcore rapper was decidedly different from the kid-friendly marketing campaign that was rolled out, complete with action figures. At that time, two of the biggest acts in rap were New Kids on the Block and MC Hammer. Ice was supposed to fill a gap between the two.

The end goal was to have Ice do for hip-hop what Elvis Presley had done for rock ‘n roll. But while segregated radio meant that early rock ‘n roll was still fairly obscure to Elvis’ fans, when Vanilla Ice broke, “Yo! MTV Raps” had already been on the air for a couple of seasons. While Vanilla Ice was being embraced by bubblegum pop fans, he was being derided as a fraud by hip-hop fans. At the same time, the Milli Vanilli lip sync scandal broke (taking C+C Music Factory, Black Box, and Technotronic down with them). The rise of gangsta rap and grunge was in part a response to the years of actual fraud perpetrated by these acts, which left music fans hungry for something far more genuine and authentic. A lot of acts perceived as pop were suddenly guilty by association, simply for sharing the same genre.

And no one was hit harder than Vanilla Ice. In 1990, his debut album, To the Extreme, was number one for sixteen weeks, selling 500,000 copies a day at its peak. A year later, his follow-up live album failed to crack the top twenty, and his movie debut, Cool As Ice, barely made more than $500,000 at the domestic box office, getting pulled from theatres less than a month after its release. In 1992, Ice was so detested that the white rap group, 3rd Bass, scored a hit just by having Henry Rollins lampoon him in their video for “Pop Goes the Weasel.”

Perhaps then, Iggy Azalea could be on a similar career trajectory. Like Ice, there seems to be little genuine sense of who she is. A description of her hometown of Mullibimby reads similar to the bohemian arts haven of Taos, New Mexico. Azalea herself has talked about her humble background, and has said that she and her mother worked as house-keepers in the vacation homes of Mullibimby’s more affluent residences. When Azalea moved to Miami as a teenager, she went to work as a hotel chambermaid.

Aside from her song, “Work,” there’s little indication of the effect of her background on her as an artist. Frankly, she spends most of the song judging women who exchange oral sex for designer shoes. Perhaps her real crime isn’t being an Australian woman trying to sound black, but that she’s cultivated a mean girl persona to sound black. While trash talk is practically its own sub-genre, she lacks cleverness, and sounds like she’s punching down in order to build herself up.

So, is Iggy Azalea the female Vanilla Ice? In terms of marketing, absolutely yes. They were both sold to pop audiences rather than rap audiences. While Ice eventually said in an episode of Behind the Music that he sold out, Azalea doesn’t strike me as having any morals to compromise. As for actual talent, one of the things Ice had going for him was that he was a good dancer. He did also show some real promise as a rapper, and if he’d been in more of a position to hone his craft like Eminem, instead of being thrown onstage as a kind of rapping New Kid on the Black, he might have developed some genuine artistry.

For her part, in a recent radio appearance, Azalea was asked to freestyle, and she balked. If you can’t freestyle, you’re not a rapper—race and gender are irrelevant. This should end her career, but it probably won’t.

When I wrote that Rock is Dead, I didn’t put enough emphasis on the fact that the under-30 audience sees rock as old people music, the way my generation (Generation X, I suppose) saw jazz as our grandparents music. For young people today, music is electronic dance music, R&B, and hip-hop, all with a great deal of overlap. Younger music fans aren’t plagued by the same questions of authenticity in regard to race and genre because they learned music appreciation from the Disney Channel and Nickelodeon. Also, Auto-tune has made it easier to sell attractive people who can barely carry a tune; I don’t see another Milli Vanilli-type scandal on the horizon.

So Azalea’s career trajectory may not parallel Ice’s, but that isn’t because she’s more authentic or talented. It’s just because the audience is willing to put up with less authenticity for longer. The public turned on Ice, but we’ll probably just get bored of Iggy.