(or everyone has tunnel vision except me; or in the land of the blind, everyone is blind)

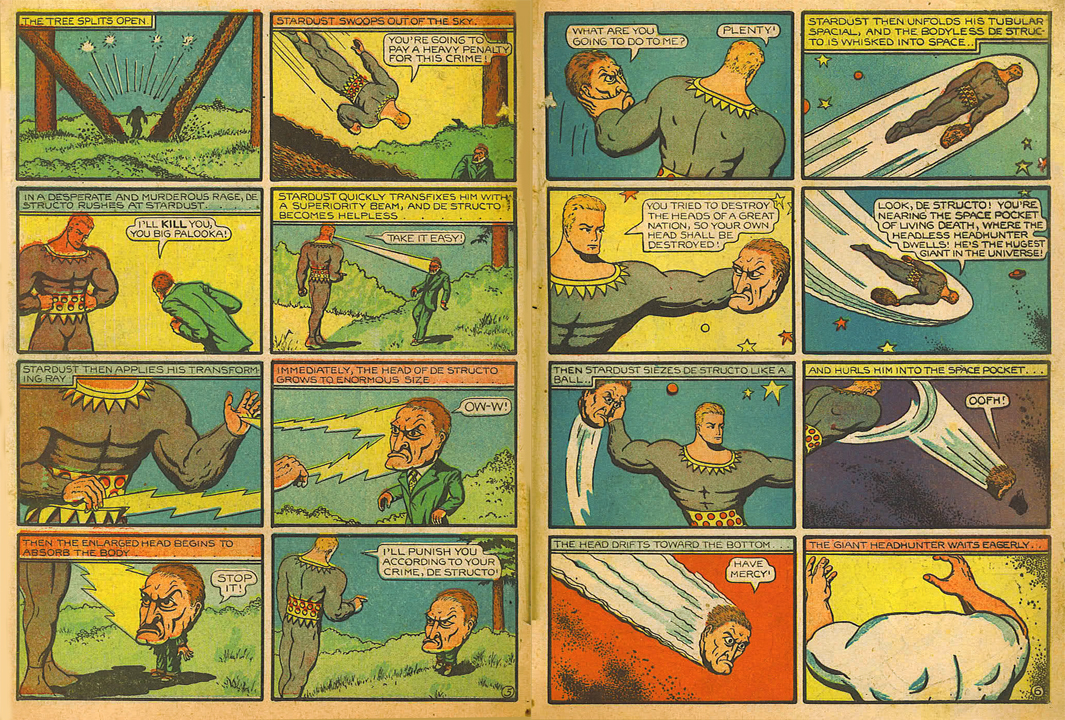

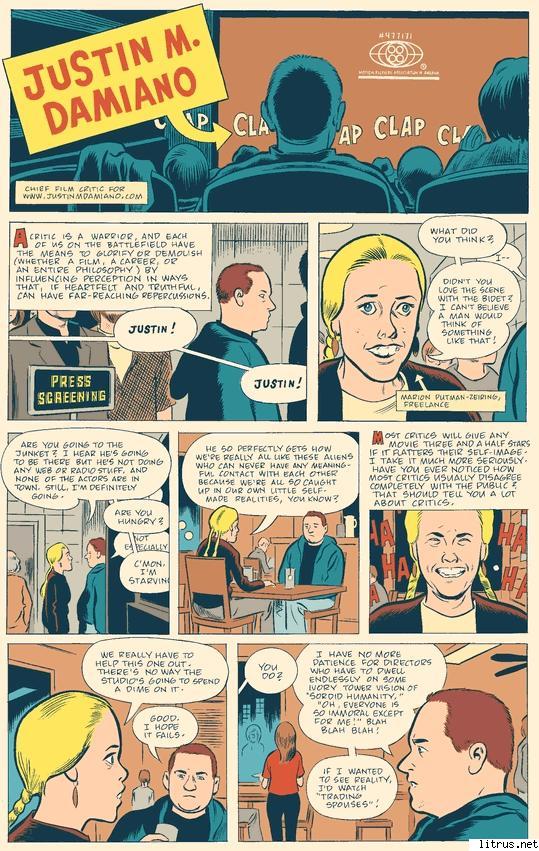

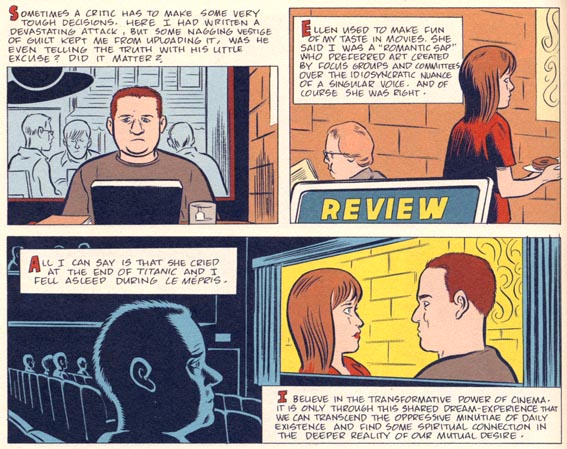

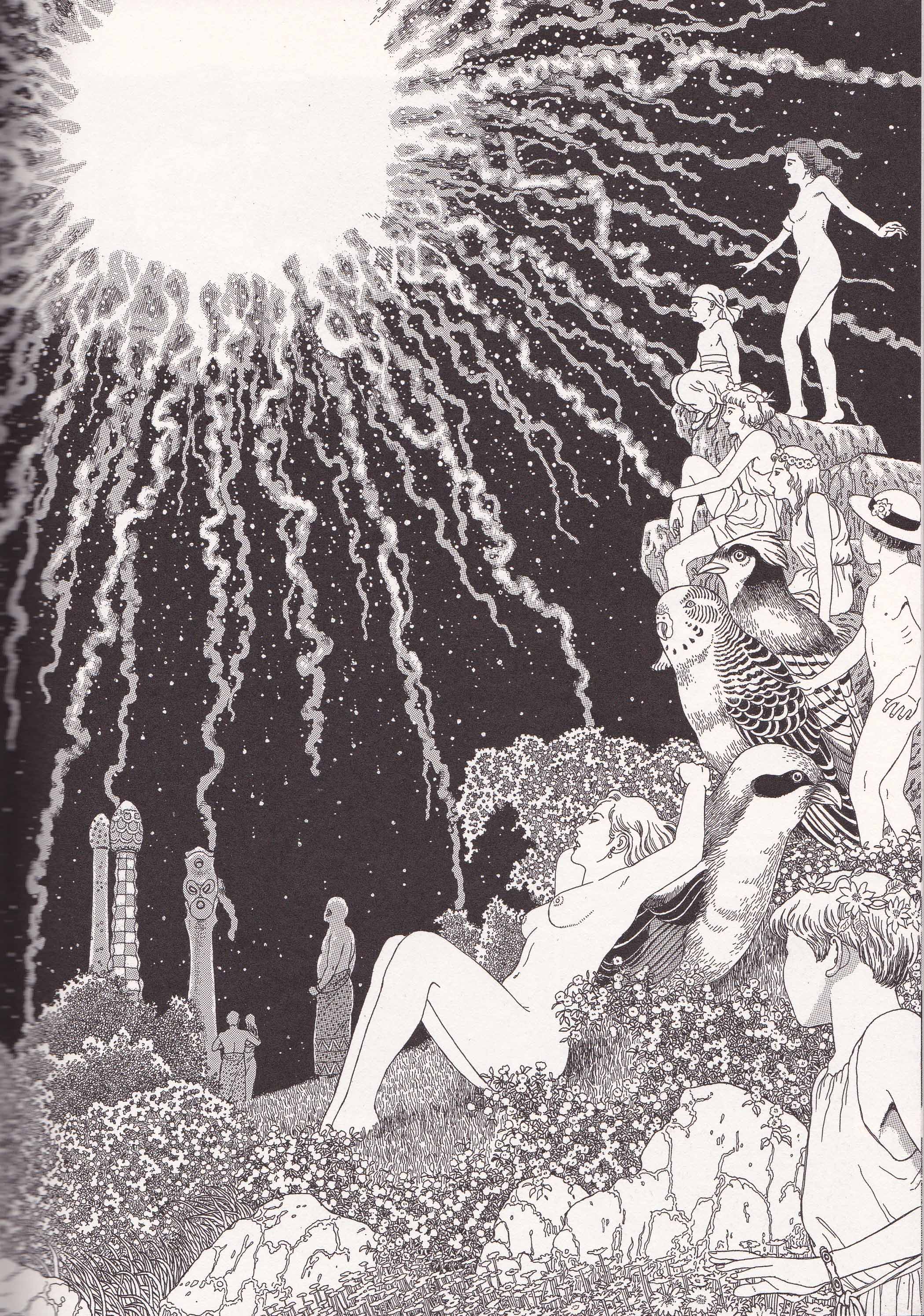

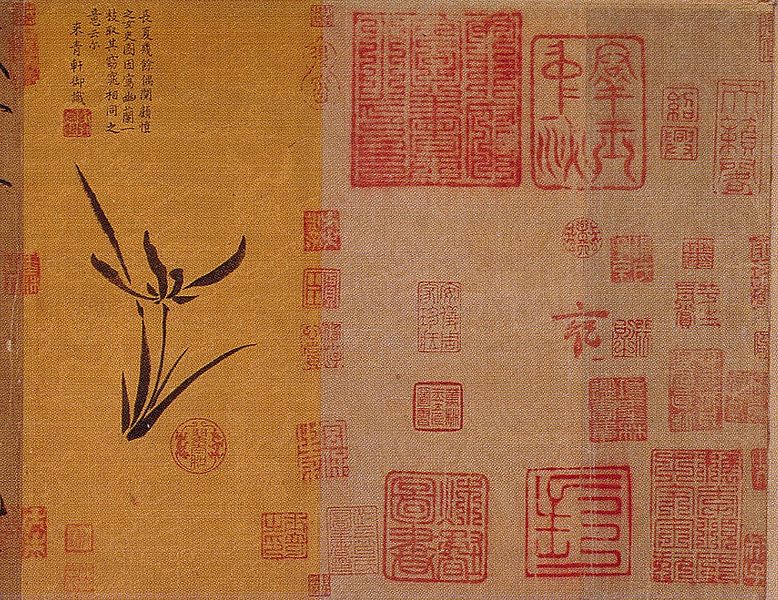

[Allegory of Comics Criticism by Wallace Allan Wood]

TCJ.com recently published an exchange between Frank Santoro and Sean T. Collins concerning the state of comics criticism (c. 2013).

In his prologue, Santoro expresses concern about the neglect of a whole new generation of cartoonists now as much wedded to the world of the internet as to paper.

“… the small subculture of engaged comics reviewers is getting older, myself included. I really hope that members of the younger generation will start writing about each other. I’m seeing some hints of it here and there, but not many organized voices…The “pap pap” demographic of comics is so insular – which is fine – but out on the circuit younger makers are telling me that they never read this site, or any websites related to comics at all. There’s really not much for them in most comics sites that reflects their tastes or their concerns.”

Some questions should spring to mind immediately upon reading this. Why is it of special concern, for example, that younger makers of comics are not reading TCJ.com or any website related to comics at all? Are they representative of the alternative comics readership as a whole? Or are they simply the kind of people Santoro would prefer read TCJ.com and comics criticism?

Comics has a long history of cartoonists not engaging with criticism and critics at all; they for obvious reasons preferring the company and conversation of their “own kind.” No doubt long time comic aficionados will begin pointing to the classic comic histories or the critical works of Seth, Chris Ware, Scott McCloud, Art Spiegelman et al. It should be pointed out, however, that the very idea of a negative critique is anathema to this school of criticism (unless it is directed at blind intransigent critics). It is adulation and evangelism which is required. Such is the rarity of this engagement that one might say that the arrival of a celebrated cartoonist into the unhallowed halls of comics criticism is, more often than not, greeted with a joyousness befitting the arrival of the Queen of Sheba (the royal metaphor here being no accident of choice).

The attitude of young comics makers conforms to this pattern. They are merely ape-ing the behavior of their forebears. What was once good for the artists of Fort Thunder (and its adherents)—namely steadfast, earnest positive promulgation—is now good for the new web-based alternatives. Collins returns to these concerns towards the close of the dialogue:

“The other big problem, maybe the biggest, and certainly the one that’s worried me the most and I think inspired my whole end of this discussion with you, is that there’s an entire generation of young artcomix makers whose work just isn’t being reviewed at all. …An entire generation, an entire movement, of altcomix creators who are doing vital, defiant, personal work is badly undeserved by criticism, and that will have a huge effect on both comics and comics criticism moving forward.” [emphasis mine]

This might certainly be of concern for readers (and critics) with a long term interest in sustaining the comics grassroots. It might in fact be seen as the duty of committed blog aggregators (with a compliant readership) to push links to these sites on a more frequent basis and for publishers to consider the best of these for print publication and more sustainable retailing. Comics critics who see themselves as evangelists and want to sideline as marketing agents for the small press may also choose to delve into this. Indeed, the vast majority of comics reviews do in fact fall into the category of marketing. There is no reason why these hats cannot be put on or taken off at will. There are even college courses in marketing for those so inclined. One might even consider being reborn as Peter Laird (of the Xeric Foundation) or Kevin Eastman (of Tundra).

But all this is of secondary importance to the state of comics criticism. Last time I checked, The Comics Journal was supposed to be the magazine of news and criticism, not the Journal of Comics Marketing. Collins’ concern that the artists of the Happiness anthologies are not being reviewed suggests that he is concerned that they are not being covered positively and disseminated widely—that they are not being sold to a whole generation of readers. This would appear to be the primary purpose of comics criticism in Collins’ view.

I beg to differ. If you want to sell things, then sell them—send them to famous cartoonists, influential publishers, and comics critics who are interested in selling things. One influential Tweet by a comics celebrity will do more good than a 3000-word review of the highest quality produced by a nobody. And for god’s sake, don’t send your comics to critics who want to criticize them. Find someone who cares more about how many copies you sell than about the quality of your work. If we could only separate these comics critics from comics marketers, comics criticism might be in a more healthy state.

Comics must be the only art form where the most prominent commentators in the field (who shall remain nameless) regularly dismiss or deprioritize discussions of the art form they are engaging in. The art form I am referring to is not comics but criticism. Santoro’s comment that he “noticed that [he] wasn’t taking the time to read long reviews or blog posts” (in the last few years) is not a new phenomenon but purely a symptom of this modern age—an age of endless distractions and diminishing attentions spans. The idea that someone might take a copy of The Comics Journal on a long plane flight as reading material (as Tucker Stone has admitted to doing at least once) could be taken as a sign of mental illness or at least an eccentric attitude towards comics.

Comics criticism doesn’t actually need more people who are interested in comics (that is a given considering the insular nature of the hobby); what it needs is people who are interested in criticism. Collins’ main concern—that the comics he likes aren’t being reviewed—is understandable but should be of little concern to comics criticism per se.

* * *

Santoro and Collins began their discussion with much broader concerns, starting with the number of comics reviews being published of late. This question of quantity is first directed at Collins who answers:

“Less. Certainly less as far as alternative/art/literary/underground comics go. It seems as though there’s as much of a profusion of reviews of superhero comics as ever.”

Any proclamations on this topic are guaranteed to be anecdotal and unscientific but my impression is that there has not been a drop in the quantity of long form criticism concerning non-superhero related comics since I started monitoring the field more closely. Santoro suggests that there was an apparent golden age from 2008-2009 “when 1000-word reviews were common.” No doubt quality is always preferable to quantity but a 1000-words can hardly be considered the high water mark of long form criticism. Perhaps it is the bare minimum Santoro demands but 1000-words often suggests:

(1) “I don’t have enough space or money to pay you for more”, OR

(2) “I don’t want to waste my brain cells on this so I’m going to vomit out whatever is on the tip of my tongue”.

600 words for opinion and short analysis (at best), 300 words for the gloss and information, and 100 words for padding and style don’t often add up to much in terms of essential reading for the informed except in rare circumstances. A little more leeway might be found in instances where the work has been thoroughly assimilated by the comics community and a tighter focus brought to bear on the subject matter. 1000-words is of course the “industry standard” for long form criticism and not something to be especially proud of. As a purveyor of this kind of material, I should know. The call for 500-word reviews (to increase coverage) during the closing years of the print Journal certainly heralded the arrival of poorly substantiated opinion as opposed to analysis. A publisher’s synopsis and an Amazon.com comment would have worked just as well in this instance.

The short form approving review or “call to purchase” is tailor-made for the comics critical community, a grouping which is largely unpaid and interested primarily in fellowship—the generation of comments and making friends on Facebook and Twitter. Collins points to this early in the exchange where he writes:

“It’s exceedingly easy to type up your strongest single impression of a new work and post it to Facebook, Twitter, or Tumblr, and receive feedback almost immediately. And since your strongest single impression could be nothing more complex than “This is SO GOOD, you guys,” and the feedback can just be a like or a fav or a reblog or a retweet or a share, it’s tough to build up a thoroughgoing interrogation of a comic. The energy is diffused.”

The motivations for writing comics criticism are many and this is but one possibility. Some might do it for pocket change while others might participate in the interest of generating a conversation by which process they might attain enlightenment or at least a modicum of self-improvement. If one desires a large readership and a huge reception on Twitter, then an article on a superhero comic would increase the probability of this (preferably a controversial one). To expect a substantial response when writing a review of an alternative comic with a readership in the low thousands (or hundreds) at best would be to deny reality. At the risk of stating the obvious, people are interested in what they’re interested in. They are unlikely to read, comment on, or even click on a link to an article about a comic or subject of which they know nothing about. In fact, the best way for a comics critic to get an audience is to not write about comics at all—easily one of the least popular art forms extant today.

The problems associated with writing good, well researched long form comics criticism mirror those found in the creation of alternative comics with a marginal readership. The present day solution to these problems is echoed in both endeavors. If one desires quality criticism of the alternatives in the field then an altogether different attitude (and critic) is required. This is the kind of critic who primarily writes for herself or at least because of some deep inner need (pompously metaphysical as this may sound). It is a simple equation. You write criticism because you have something to say, because you feel compelled to write about it, and because you want to do the best job you can (as would any artisan). The need for an audience (and this is an ever present gnawing desire) must come only after this. The available readership for comics criticism is limited by the popularity of the form and the attractions of the topic or comic being written about; much less so the quality of the criticism.

An actual increase in the volume of comics criticism is not necessarily desirable or even achievable considering the state of the industry and art form. A different lesson presents itself if one considers the titans of comics. Kirby’s oeuvre, for instance, would have been substantially enhanced had he the luxury to draw and write less and not more comics. In the same vein, I would much prefer it if unusually prolific critics would write substantially less but longer and more considered reviews. Which makes Collins’ point later in the exchange appear somewhat wrongheaded:

“My point, ultimately, is that without a sufficient volume of reviews being written, you’re not going to see needed critiques — particularly since most people are writing for little or no money, and most humans like enjoying themselves if they’re not getting paid, and it’s generally easier to enjoy yourself if you’re thinking about something you like instead of something you don’t.”

It is not critical volume which is required but concentrated quality. The idea of twenty 500-word articles on Alternative Comics X does not please my mind in the least and would certainly not be an advancement over just one good long form article on the same comic.

Monitoring the comics critical scene is an endless drudge considering how often blog aggregators point me to worthless plot synopses and marketing copy masquerading as reviews. Even worse is how little effort they spend differentiating between this excrement and the truly worthy articles which generally get lost in the shuffle. In any case, the state of coverage is considerably better than was the case back in the 80s and 90s when The Comics Journal (the print version) was virtually the only game in town when it came to non-superhero related material. Not being reviewed in the Journal (for good or ill) in those days was tantamount to not getting reviewed at all. Since then, the state of comics criticism has been enriched by voices emerging from the fields of academia; a not surprising new source considering this grouping’s dedication to thinking, reading, and writing about things. A number of these writers emerged from fandom and it is high time fandom looked beyond its own narrow shores to the wider world of critical writing if only in the interest of improving itself.

* * *

Side note:

Noah commented twice on the article at TCJ.com; I understand with some irritation that the site you are reading was left out of the conversation when it turned to subjects such as long form comics criticism and analysis, extended comments sections on subjects other than superheroes, female writers, and coverage of non-superhero related material.

He should not be surprised or overly concerned. To put it bluntly, The Hooded Utilitarian is a pariah site as far as the traditional comics community is concerned—reviled primarily because of its owner and a lack of correct communal spirit. Others might add lies, bad faith, and a lack of “professionalism” to the mix. To expect consideration from a school of comics criticism which you have rejected is perhaps asking far too much. Like a lump of shit, the only instance in which they might care to notice this site is if they stepped on it accidentally.

HU is not exceptional in its pariah status. The manga community is yet another example of a group of “comics untouchables”, a community with women writers and readers in far greater abundance than on HU. Which leads to the inevitable conclusion that, for all intents and purposes, women are the Dalits of comics, alienated by virtue of the types of conversations which engage the longstanding comics critical community of males. It might be that in their view, it is the men who helm the traditional comics conversation who are to be avoided. They also don’t need anyone to fight their battles for them (see comments by Peggy Burns, Sarah Horrocks, and Leah at the original article) .