I’m probably overly pleased with this comment from the ongoing theory vs. art debate…but, hey, it’s my blog, and I will highlight it if I want to:

In terms of instinct…I sort of said this before, but…I don’t think the kind of instinct you’re talking about in terms of art is the same as the general understanding of the word instinct. That is, it’s not the same as the instinct which makes a lizard bask in the sun, or a bee go to a particular flower. Those are instincts that are outside of language; they’re innate.

Making art though isn’t instinctual. It’s learned. And what’s good and bad in art isn’t instinctual either. It’s part of a communal or social agreement or process. Art is like language; it’s a form of communication, which makes it shared, not isolated. That’s what Hauerwas is talking about when he says imagination is a communal project. It exists within a society, and that society gives it meaning (and, arguably, vice versa.)

When I make art (whether poetry, art, criticism, or whatever) it’s obviously something of a mysterious process. Any thinking is, because we don’t know ourselves — in large part because so much of ourselves are other people. In that vein, I’d argue that the praxis of art making is itself infused with ideas; what you create, how you create is, what you think is good and what you think is bad, is all dependent on a conversation with other artists, with other critics, with ideas and arguments. Art is made out of other art, the standards of art come from other art, and that making and those standards are a discussion.

My problem with making that into a shorthand called “instinct” isn’t that it’s untheoretical. As I noted before (and as Bert did), I don’t really know that artists necessarily benefit from reading theory. But…making art into instinct makes art seem like a lizard sunning itself, or a person urinating. Art’s not a natural process like that. It’s a social thing and a cultural thing. Which means that art is never one voice; it’s many different voices. Criticism isn’t an outside thing that takes away from praxis; criticism is praxis, and vice versa. Thought and intellect are what art is made of, just as they’re what people are made of, to the extent that people aren’t just animals (of course, people *are* animals too…but art is not the animal part.)

I mean…it’s possible that I’m misunderstanding you and that you in fact agree with all of that. But when you appeal to temperament or instinct, it seems to me like you’re trying to deny the social and communal aspects of art. The artist is alone with her instinct, creating a thing of beauty which is beyond analysis. Humans do arguably create things like that — they’re called children. And despite the artful comparisons of metaphor, art isn’t children.

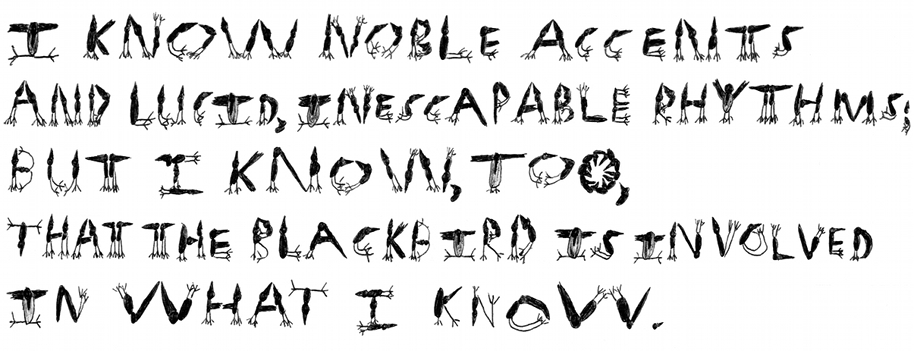

The point is, when you say that without instinct art is nothing…that’s an aesthetic opinion, which one can agree or disagree with. But without intellect without language, there literally can’t be art. In that sense, criticism, or language about art, precedes art itself.

And, just to make this a little less solipsistic…here’s Bert Stabler talking about radical and conservative art.

Well, we just have, at bottom, a “conservative” and a “radical” stance. Zizek of course privileges the radical, but I don’t, out of hand. Franklin and Alex see an old order, a natural harmony, an organic tradition that surpassed language, invaded and overturned by an alien force, a new regime of arbitrary artificial homogeneity. Caro and Nate (and to an extent Noah and I) are agitating on behalf of a foundational tension, rather than a foundational order, within which Theory is only the latest in a series of attempts to cope symbolically (through language).

I think there’s kind of a historical pendulum (swinging but also rotating– you know, rotation of the earth and all that)– the Enlightenment gave us liberal universalism, and the 19th century reacted sharply, with conservative particularisms (colonial revolutions rather than domestic ones), fighting for sacred tribal earth. The twentieth century brought conservative universalism in the form of various large-scale assertions of absolute truth, and one might hope that this century would grant us some liberal particularism. That means that the totalizing arrogance of radical stances needs to start recognizing boundaries, and the vicious purity of the conservative will have to be redefined in humility.