A week or so back I wrote a piece for Salon in which I talked about the way in which self-publishing and ebook erotica has fit into and challenged romance genre themes and conventions. In the discussion, I talked about Janice Radway’s classic 1984 study Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy and Popular Literature.

I’ll admit, I hadn’t quite realized how controversial Radway’s study is. Romance readers, it turns out, hate it, arguing that it’s condescending, simplistic, and blinkered in its narrow anthropological focus on one small group of romance readers. They also are infuriated by Radway’s suggestion that romance provides women with a compensatory escape from unsympathetic husbands and lives stifled by patriarchy. Pam Rosenthal added that she was “pissed re use of Radway cuz it ignores a generation of feminist-inflected romance discussion since then.”

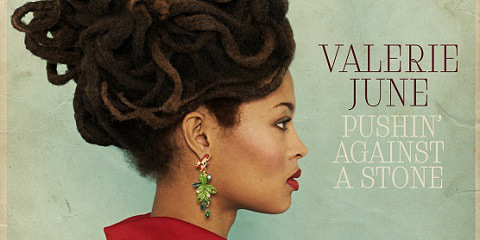

In the course of the twitter conversation, Janine Ballard recommended a couple of romance novels that she thought might challenge my view of the genre (and perhaps make me more skeptical of Radway.) Two of the books she suggested (both regency romances) were Cecelia Grant’s “A Lady Awakened” and Pam Rosenthal’s “The Slightest Provocation.” So, having read both (and enjoyed both, with reservations) I thought I’d talk a little about ways in which they do, in fact, seem to dovetail with Radway’s discussion, and ways in which they don’t.

The most intriguing part of Radway’s argument, to me, is her suggestion that romance novels are an expression of a desire for nuturance which, she suggests, is often denied to women in patriarchal society. Using the theories of Nancy Chodorow, Radway argues that romance novels imagine men who, beneath a hard, distant exterior, are actually soft and nurturing. Romantic heroes are mothers in disguise.

Both Rosenthal’s “The Slightest Provocation” and Grant’s “A Lady Awakened” fit this theory surprisingly well. Or at least, both take care to link mothering and romantic love. Grant’s protagonist, Martha Russell, has at the beginning of the novel just lost her drunken husband. Without an heir, her home will go to his brother, known among the servants for having raped multiple housemaids. In order to prevent that, Martha engages Theo Mirkwood, a neighboring sensualist exiled to Sussex by his father, to sleep with her every day in hopes of producing a heir that can be fobbed off as her former husband’s. Theo, then, is not so much a lover as a mother-maker, and Martha’s emotional isolation is specifically tied not just to her lack of love for men, but to her barrenness. Anxieties around mother-child are paired and mirrored in the anxieties around lovers, so that both are solved simultaneously — with Martha able to nurture a child when she finds herself able to allow Theo to nurture her.

The plot of Rosenthal’s “The Slightest Provocation” doesn’t deal with mothering so obviously. But its first scene makes the connection very strongly, as Emilia, the Marquessa of Rowen, bonds with her first baby and simultaneously regrets her husbands lack of affection. In a passage that (given the rest of the text) is pretty clearly supposed to be erotic, Emilia prepares to breastfeed, noting that “She felt the most remarkable sensation in her breasts, which had grown hard, and moist at their tips.” But then a wet nurse comes and takes the baby away, in part so that Emilia will be ready to have another baby (a back-up heir) in short order. “The milk and her tears dried up, and her menses started again a few weeks later.” Again, the thwarting of motherhood and the thwarting of romantic love are linked. Romance means mothering; a loving man becomes loving mother. The delight is in the gender mix-up, as Rosenthal makes clear in a remarkable passage.

Confusion, befuddlement, sweet sea of swirling distraction; she couldn’t tell (didn’t know and obviously was in no position to say) whether she was moving or sensing, doing or done to, lover or beloved or both at once.

Was it possible to be both at once? Could one sort it out, separate the each from the both of them, find the beginning or skip ahead to the ending? While the snake swallowed its tail, beyond words or thought, where there was only the endless circle, the ring of pure light, the blank low sound of ohhhh, words faded to humming, ecstatic spiral of sensation? After heroine and hero have pushed and pulled, teased and taunted, come and gone and come and come again, to this quick, bright, simultaneous and happy confusion, bonds loosed and boundaries no longer distinct? Where does one pick up the story again, the then and now, he and she, lover and beloved?

Radway, paraphrasing Chodorow, argues that romances are based in the fact that women, unlike men, “possess quite permeable ego-boundaries…their adult internal psychic world…is a complex relational constellation that continuously demands the balnce and completion provided by other individuals.” As a description of all women everywhere, that seems pretty reductive, but as a gloss on what’s happening in that passage from Rosenthal, it works nicely. A utopia of pleasure in which ego is lost and relation becomes the self, a “ring of pure light” which seems like it could describe birth as easily as sex, with “boundaries” between selves “no longer distinct.”

Radway tends to see this imagined feminine utopia of love, interrelation, and mothering, as compensatory — it is as a way to escape from an unpleasant patriarchal reality in which men are not caring and women are not nurtured. This, too, could be seen as fitting both Grant and Rosenthal’s books — though in a more consciously feminist vein than Radway proposes. That’s because both authors are quite explicit in presenting love and relation as a solution to, or antidote to, patriarchy.

In “Awakened,” for example, Theo, the wastrel, finds his sense of duty and ambition through his love of Martha — and that sense of duty and ambition makes him, not a masterful hierarchical patriarch, but an egalitarian leader by consensus.

When had he become this man, as easy about command as though he were born to it? He gave respect in extravagant handfuls, never fearing he might diminish his own store — and indeed he did not. The more he deferred to the expertise of others, the farther they would follow him down any path. One could see that in the way people stepped up to undertake this or that part of his plan.

In complement, Martha’s love of Theo leads her out of her widowed isolation; he gets her neighbors to call on her, much to their pleasure and hers. In her troubles he tells her “You have more allies than you know, if you would only learn to trust them” — which is a prelude to the entire community uniting against the dastardly Mr. Russell and forcing him to give up his desire to take possession of Martha’s house. Love is not just an individual troth, but a communal good, which binds men and women, masters and servants, laborers and landowners — and banishes evil, here figured deliberately as the patriarchal monstrosity of the rapist.

“The Slightest Provocation” is just as sweeping. Set in a period of famine and labor unrest in England, the love of Mary and Kit prevents bloodshed and thwarts the British government’s patriarchal schemes to foment revolution in the interest of passing repressive legislation. Mary’s long delayed declaration of passion “My husband, my darling my only love—” is issued as Kit and she are in the middle of an elaborate ruse to dissuade a number of laborers from marching on London, where they will surely be arrested and perhaps eventually hanged. Love saves lives and bridges class — a truth underlined even more emphatically at the end of the novel when we learn that Kit is the illegitimate son of Lady Emilia’s carpenter and worker, Mr. Greenlee. The novel that began with Emilia barren of milk and love ends with her and her long-time working class lover happy in the knowledge that their son, Kit, has found happiness as well.

I’d argue, then, that Rosenthal and Grant don’t contradict Radway’s analysis so much as they complete it. Radway, again, saw the romance as a kind of idealized feminine vision created in the teeth of male reality; a fantasy in which the barren partitions of patriarchy could dissolve in a nurturant bi-gendered relational egolessness. Rosenthal and Grant certainly respond to that vision — but they, like Radway, draw out its political subtext. In these novels, the 19th century setting, portrayed in loving realistic detail, is exciting precisely because its rigid hierarchies are so ripe for overthrow — the patriarchy bending and flowing into sweet, soft communal affection. The purpose of the Regency is to save the Regency for, and with, feminism. If Radway had written romances rather than anthropological treatises, you have to imagine that these are the sorts of romances she would write.

_______

While I think Radway would love these books, though, I can’t exactly say that I did. Both of them were well-written. Grant in particular, is a masterful stylist. This description of one of Martha and Theo’s first sexual encounters, for example.

Her hands fell at random places on his back and stayed there, passively riding his rhythm like a pair of dead fish tossed by the sea. Or rather, one dead fish. The other still curled tight, like a brittle seashell with its soft sensate creature shrunk all the way inside.

That’s lovely, and also bitingly funny — the sort of thing Jane Austen might have written if she’d been willing to follow her characters into bed. And then there’s this scene, again in bed:

“My mind rules my body. Not the other way round…..”

“I’ll pleasure your mind as well. I’ll speak of land management the whole time.”

“You’re depraved beyond my worst conjectures.

The joke is, she really is obsessed with land management. I laughed out loud at that. Why can’t rom-coms ever have banter that witty? For that matter, why exactly is romance so universally considered to be crap while Elmore Leonard or John LeCarre or J.K. Rowling or for that matter Jonathan Lethem are supposed to be taken seriously? Grant’s prose is better than all those folks’, I’m pretty sure.

At first, as I was zipping through the ebook, I was planning to buy everything Grant had written and read it ravenously. I wasn’t quite as enthusiastic about Rosenthal, but still I enjoyed her high spirits, her forthright sensuality, and her sly meta-moments. There’s a very clever passage in which Peggy, a servant girl muses about the pleasures of following the lives of the nobility, and thinks about how her sisters ; “real-life problems are dull and intractable,” she notes. “Peggy didn’t see why you shouldn’t get a little amusement from people whose lives remained cozy and comfortable…” A neater apologia for romance couldn’t be penned.

So, if there’s so much to like about these books, why the reservations?

In two words, the end. The end. The cheerfully feminist, sweepingly optimistic end.

Don’t get me wrong; I know romances end with the main characters happy. I’m not against that. On the contrary, I really, really liked ramrod-straight, censorious Martha and dissipated but puppy-dog eager Toby, and Rosenthal’s Martha and Kitt as well. I wanted them to get together; I wanted them to be happy. But does everybody need to get a happy ending? The eloped couple stopped before they do anything rash; the silent, bitter former maid given her moment to confront and overawe her rapist; evil plots foiled; every couple united; the very cows singing with content. “Lady Awakened” won’t even allow any deception, no matter how prudent, to mar the march of aggressively joyful virtuousness, and so the book’s long, exquisite representation of reticence is released in a single artless confessional belch.

Again, I think I understand the appeal. The vision of love uniting everyone, the idea that romance can usher in not just personal but political utopia, is part of both books’ central message. But, for me at least, it’s just too much. My belief in the love is supposed to guarantee the utopia, but instead the unlikelihood of the utopia undermines my belief in the characters and their affection. The world just doesn’t change that easily; pretending that it does knocks me out of the fantasy and makes me depressed. Elizabeth and Darcy are real in part because Charlotte Lucas and Elizabeth’s ninny of a sister are there to show that, yes, this is the world I know, where stupid people stay stupid and people have to make compromises, and not everything turns out for the best for everyone. But in “Lady Awakened” and “The Slightest Provocation”, utopia eats the characters. There, in the steady, omnipresent light, they cast no shadows, turned into flat, smiling ghosts, lobotomized advertising images selling equality and love with a blank, depersonalized cheer.

Complaining because a utopia is unrealistic is a bit pointless, I guess. And of course you could conclude that I’m not the intended audience here and leave it at that. But the thing is, I want to be the intended audience. I want the happy ending. For that matter, I find the feminist utopia appealing. I want more bitter in my sweet not because I disdain the genre pleasures, but because I crave them. Maybe, after all, these romances could use a little more of Radway’s pessimism; a little more of her second wave view of patriarchy as a bleak, not easily movable weight. I fear I need a touch of sadness and despair in order to access the joy.