If you talk about white people, you’re not talking about race. If you talk about black people, you are. This is arguably the essence of racism; black people are an aberration or a disturbance; white people are natural. Therefore, to end racism, artists should treat black and white individuals exactly the same. If art doesn’t see color, then the art isn’t racist. QED.

This is the logic that Lamar one of the co-creators of the Pixies’ video “Bagboy,” used when he defended his decision to present a narrative in which a white kid gleefully and giddily trashes a house which, at the video’s conclusion, turns out to belong to a black woman who he has trussed up in her own bedroom.

We knew we were taking some risks when we made the video. When most people see a white kid (Nik’s little brother) and a black woman (my older sister) they can’t help but think “racist” and “misogynist”. This is pretty sad.

From the beginning, when we originally thought of the concept, it was never our intention to make it about a white kid terrorizing a helpless black family. I, myself, being black have gotten to the point where I don’t automatically see color in people. It’s the same for Nik. If the character’s races were switched you’d probably have the same amount of stuff to say about the video.

It’s 2013, at what point do we stop seeing everything as racist. At what point do we stop making things a bigger deal than they are.

The problem here, as Bert Stabler points out, is that claiming color-blindness doesn’t make the rest of the world color-blind. Declaring racism over doesn’t make it so, and there isn’t really any way to show a white kid terrorizing a back woman’s home without referencing the way that white people really have, in the recent past, conducted vicious campaigns of terror against black people for daring to move into middle class homes. The video doesn’t come off as color-blind; it comes off as thoughtless, or (as Bert suggests) as cynically courting controversy. Not seeing race now can’t erase a history of racism, especially when not seeing race seems to just result in you unthinkingly mimicking that history.

Danity Kane’s Ride For You does a much better job of suggesting that race doesn’t matter, though not exactly by ignoring race.

Towards the end of the video, the five female members of the interracial group pair up with various hot guys. Those pairings are integrated; there’s a black guy/white girl couple; a white guy/black girl couple, a back guy/black girl couple, and two white guy/white girl couples. This almost surely has to be a deliberate choice; Danity Kane is not a spontaneous punk rock kind of group,and everything else on the shoot, from the multiple costume changes to the round robin vocals, certainly seems focus-grouped within an inch of its life. Someone during the making of that video decided that they wanted to present a color blind world. But to do that, they had to admit (to themselves, and I think to the audience as well) that they could tell which of their singers (and which portion of their studly male window-dressing) were black, and which were white.

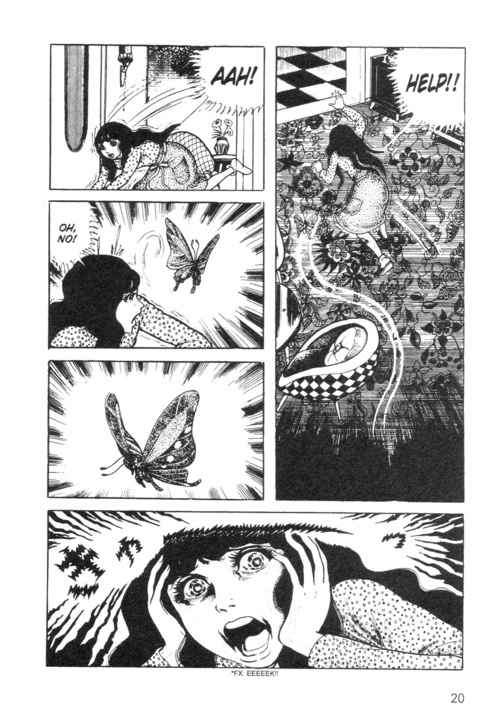

Johnny Ryan’s “E.T. on the Street” also is also quietly but deliberately conscious of race in the interest of avoiding stereotypes, though the success is more mixed.

Laurel Lynn Leake dismisses this, arguing “That whole ET comic is just “what if ET was a bl- I mean, urban man! He would be a total greedy sociopathic asshole, amirite?!” And there’s certainly something to that argument. At the same time, though, you can see Ryan (usually thought of as eager to offend everyone) trying quite consciously to avoid offense. The black guy at the beginning of the comic isn’t a gangsta, and he hasn’t been shot — he’s been hit by a car, and E.T. robs him, not the other way around. Along the same lines, the violent thug at the end is white, not black. And, for that matter, E.T.’s race is unclear. Is he supposed to be black? Or is he supposed to be a tourist in a black neighborhood — ignoring the misery there, and then pretending (with that backwards baseball cap) to be one of the folks he’s just callously robbed? Is the joke that E.T. is a black man and is therefore an asshole? Or is the joke that he’s a white guy pretending to be black, and is therefore an asshole?

The strip is conscious enough of race to make that reading plausible, and, I think, even probable. But it’s not conscious enough to exactly make that reading the point, nor to do anything with it. The end could perhaps suggest something like Crane’s suggestion in the Blue Hotel that believing in stereotypical narratives can make those narratives close around you and destroy you. But E.T.’s motivations are too much of a cipher, and his fate too random, to really sustain that. If the first part of the strip seems to be willing to think about and talk about race, the second just shrugs, abandoning the theme of racial tourism for standard-issue tropes of ghetto violence, sanitized by making the perpetrator a white guy. It’s significantly more careful about racial issues than that Bagboy video. But since it doesn’t seem to want to follow through on them, you do end up feeling, as with the Lamar and Nik effort, that race is here evoked mostly for the sake of controversy.

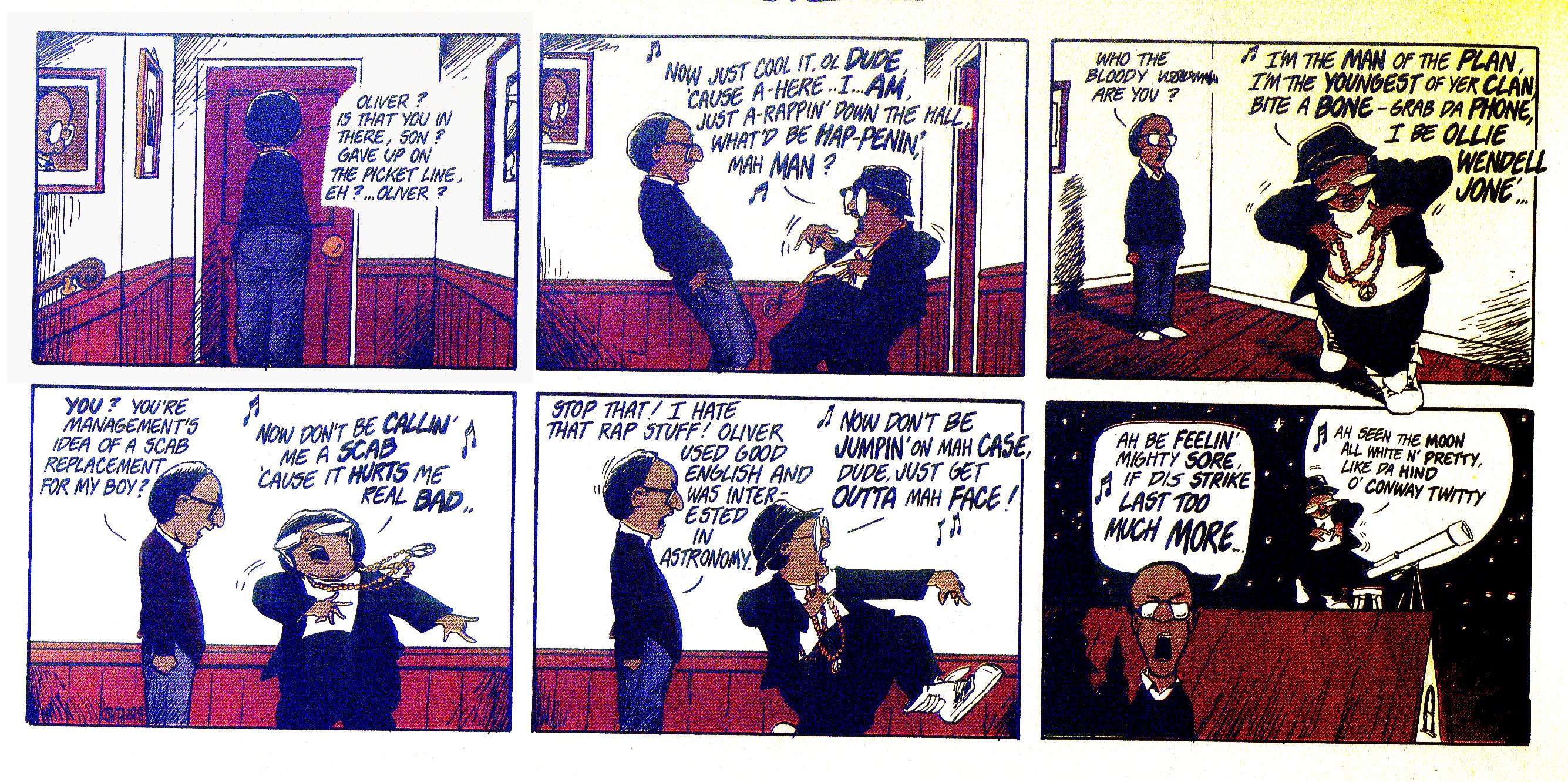

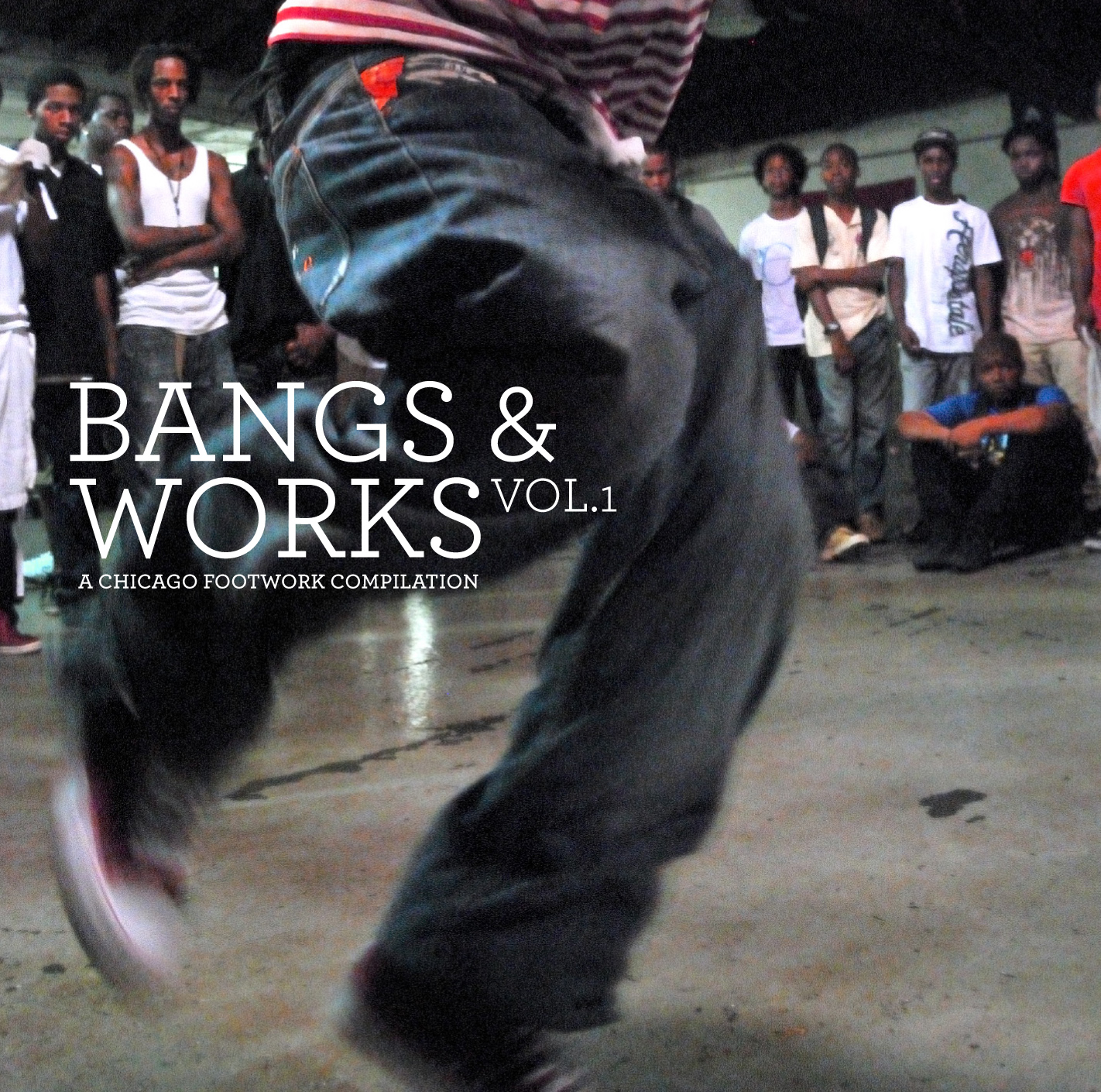

And then there’s this. (Apologies for the crappy scan.)

As with most of Berke Breathed’s Bloom County strips, this one is embedded in a lengthy and preposterous narrative. In this case, the Bloom County characters have all gone on strike to protest the shrinking space available for comics; management has hired scab replacements. Oliver Wendell Jones, the strip’s resident child-genius who also happens to be black (and whose picture you can see off to the side in the first panel), has been replaced by a ludicrous rap stereotype.

Part of the reason this strip works better than the other examples here is a function of time. Breathed isn’t working with a 3 minute video or with an isolated gag strip. Bloom County is a daily, and we know Oliver Wendell Jones like a friend. We know him so well, in fact, that he isn’t just a racial marker, as black people too often are in pop culture. Rather, Oliver is a particular person, who, like his dad says, speaks good English and loves astronomy and occasionally crashes the world’s computer networks. Breathed has put in the time to ensure that Jones is not a caricature, and as a result the reader can fully appreciate the travesty of having him replaced by one.

So in part the strip deals effectively with race because it worked to erase race. But that work, obviously, involved seeing race in the first place; making your black character a computer genius is a decision that has meaning. And the joke in this strip, too, requires seeing race, and acknowledging the way it turns individuals into the tropes we expect to see. Even Oliver’s dad, at the en, succumbs, and breaks out into rap, complete with bad grammar. In the meantime, his “son” is up on the roof, looking at the stars, and declaring

Ah seen the moon

All white n’ pretty

Like da hind

O’ Conway Twitty.

I don’t think it’s an accident that a strip about ridiculous totemic blackness ends with a ridiculous invocation of totemic whiteness. The round fat moon hoves into the panel, made visible by both telescope and verse, reminding us, perhaps, that if we must see blackness, the least we can do is remember to see whiteness as well.