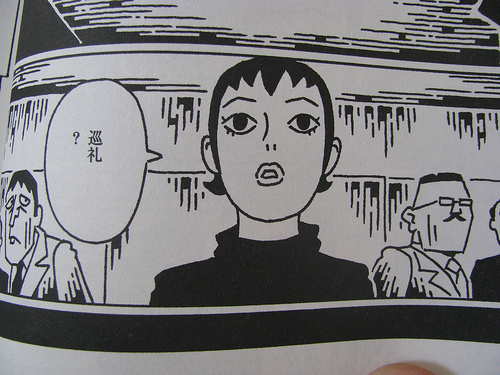

Traumerei by Shimada Toranosuke(top) and Ashura by George Akiyama (bottom), indie manga in both content and pedigree

In thinking about this post and what I could add to this discussion, I had a private goal of sneaking in and name-checking as many cool titles as possible, to proselytize those weirdo books that we love over at Same Hat (the blog I run for indie/horror/weirdo comics fans get together and talk shop). I was struck yesterday by something Kate wrote in laying out her smart and right-on points about marketing indie manga to readers. She said,

Buddha, Ode to Kirihito, and A Drifting Life are three examples of manga that appealed to a wide range of readers, from folks interested in good stories to folks interested in reading works by seminal Japanese artists. It’s this piece of the Venn Diagram that I’d like to address, in the form of three simple suggestions for marketing books to both audiences.

These are all interesting manga titles that have crossover appeal to non-manga fans, and were published by publishers other than the mainstream big companies. But are they “indie manga”? Is it the case that a work by Osamu Tezuka can even be categorized as such? This may seem like an obvious place to start, but if we’re going to discuss how to market these books, it’s important to figure out what the hell these terms mean. It seems to me that the two defining characteristics of indie manga are:

- Who licensed and published it in English

- The content of the manga itself

I wanna try to unpack these two defining characteristics in this column. A few months back, About.com’s Deb Aoki hosted a special “Indie Manga” edition of the fantastic comics podcast, Inkstuds. That discussion was a blast, featuring commentary from David P. Welsh of The Manga Curmudgeon and Chris Butcher of Comics212/The Beguiling. (I recommend that post if only for the fantastic list of titles that get mentioned as starting points for indie comics fan looking to dabble in manga). I talked there about how what we think of as indie manga is very much defined by which publisher licensed it in the States, rather than where it appeared in Japan originally.

When manga fans I know on Same Hat talk about our favorite indie manga — they’ll throw together the formalism-meets-pornography experimental works of Shintaro Kago with a horror serial like The Drifting Classroom by Kazuo Umezu and alongside Red Snow by Susumu Katsumata. For American readers it’s easy to draw a line through these titles as similar in their “indie-ness”, but looking at their demographic/publisher/bookshop placement in Japan this makes no sense at all; If Shintaro Kago is “underground” in America, he’s mega-underground in Japan– no manga shop in Tokyo save for Taco Che and other speciality weirdo shops would stock his books. Meanwhile, Kazuo Umezu is a super-mainstream godfather of gag and horror comics, and his Drifting Classroom was published as a popular kid’s comic in Japan (and is now sold shrink-wrapped for Mature Audiences in America). Lastly, Red Snow is a gekiga collection full up on realism and rural life.

In America, perceived similarities (indie-ness?) between these creators in American comic fans head space are felt because of the publisher or imprint they are published in America… but in Japan folks would majorly scratch their heads at these being discussed together.

In the introduction to Secret Comics Japan, one of the three defining anthologies of indie manga to date, an interesting and similar point was made by the editor, Chikao Shiratori. Shiratori is a comics essayists and worked as Managing Editor of GARO in the ’90, and also helped put together its spiritual sister publication (and literally the BEST primer on indie manga out there), Comics Underground Japan. In that introduction, Shiratori said:

Today, categories like “major” and “underground,” have become ambiguous and are crumbling. It might just be that the medium has truly matured, and now no single manga or manga magazine can dominate over the others as they once did… This book is entitled Secret Comics Japan. What, then, is a “secret comic” in today’s Japan where underground exist in the majors and majors lurk in the underground? In Japan, reading manga is part of daily life in almost any age group; however, things have not reached the point where your average person will actively seek out good manga, manga that will stimulate them and make them think and feel deeply. Understand, in Japan today, manga and manga-type media have become so widespread that to read manga everyday doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re a manga fan, any more than watching television regularly makes you a television fan.

Here, Shiratori hints at the other piece of my haphazard definition of indie manga — the content of the book itself! Seems to be the fundamental point of everything right? Indie to me used to mean topics and styles outside the mainstream. The weird, raw or uncommon forms of expression that you just don’t encounter without working and digging for it. This has been consistently where my comics sensibilities draw me when it comes to manga, and why anthologies such as the two mentioned above, along with Pulp Magazine and the book Sake Jock meant so much to me when I was younger — they were the Rosetta Stones of weirdo manga.

My current relationship to manga and comics in general feels different today. While my shelves are stocked with books that most likely will never be licensed into English — like the strange finds and old genre classics from my most recent trip to Japan — the world of indie manga seems vast but no longer untamed. For the initiated and devout manga fan, it’s not that hard to find out what the RAWs and MOMEs and POPGUNs of Japan are, or where the weirdest work is happening right now. (If this is you and you want to learn more and blow your own mind, I implore you to read the online English translation of the book on indie manga in Japan: Manga Zombie). Manga is awesome, sure, but the stuff I’m most excited about are self-published comics by friends and contemporaries, and Chinese and European indie comics– specifically cuz i dont know much about them! Isn’t that what “underground” is all about?

Getting back to this discussion’s thrust: it seems that indie has been used by fans and companies as shorthand for a few things:

+ Classics and Gekiga: Osamu Tezuka as Indie? How about Shojo masters like Keiko Takemiya and Moto Hagio?

+ Genre stuff that’s not SF, romance, or action: Horror serials and shorts, historical fiction, erotic comics. Interestingly enough, this is the approach that seems to often have been used on marketing European comics published here in N. America.

+ Stuff that is similar to American indies: Personal/introspective autobiography comics or stuff that follows the American “comix” scene. How often have we heard marketing refer to the “R. Crumb” of Japan, or use Tomine and Spiegelmen as their yardsticks in relating a manga?

+ Deeply weird stuff: the art and experimental comics (Yuichi Yokoyama), the genre-busting or straight-up explicit stuff (Toru Yamazaki’s Octopus Girl, Suehiro Maruo), genres we don’t have in America (gag comics by Tori Miki, Usamaru Furuya)

The Early Days! (late 1980s!) Genre comics were published piecemeal alongside other European and American genre comics. The few manga at the beginning was published in Epic Illustrated, Heavy Metal — bodacious SF and manly comics that weren’t demarcated by their country of origin, but by their adherence to genre tropes.

The Golden Years! (late 1990s!) Everyone starts taking weird changes, and Viz uses their Pokemon money to fund Pulp (spitting out art comics, genre comics, and deeply weird stuff!); To me, this was the golden age of indie manga, when it felt like the manga market pie was getting big enough that there was a piece for every reader, and every style.

Nowadays! (late 2000s!) Indie is everywhere? Or maybe we should just call them all graphic novels by now? Dynamic and interesting works are being put out by a number of publishers? In one sense, the defining characteristic seems to be a similarity to the house style/speciality of the American indie publisher that put it out…

Interestingly enough, this focus on genre stratification, and the curation role of the indie publisher (be it Fantagraphics, Last Gasp, or Viz) was raised at the very start of manga’s publishing in the late 1980s, by translator/author/manga master Frederik Schodt. Back then, he wrote an essay about manga’s potential success among English readers:

The first reason is the sheer size of the Japanese industry and the variety of material it churns out. Probably ninety-five percent of Japanese comics are not worth translating. A lot of them are soft-core porn for men or trashy romances for women, stuff we Americans could create on our own, thanks. And who wants to read volumes about the problems of hierarchical relationships in boring office jobs or the spiritual rewards of selling discount cameras in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district? But precisely because there is so much stuff produced, there is something for nearly everyone, if selected properly. You want a story on the Russian revolution, or an analysis of gourmet cooking? You wan wild, original art work? You want something that looks just like an American comic? If you can name it, Japanese comics probably have it.

I think most people who read manga in America are not aware of the fact that the filter is huge. The filter that an American publisher is using when they decide what to publish here is very big and tight and they ultimately have to import what they can sell here, which is not what someone in Japan would necessarily want. That’s why for years all the manga here were kind of SF, young male-oriented works. It’s only recently that shojo manga caught on, which was a big surprise to everybody in the industry. Even to this day, I’m not sure how much of the popularity of manga is here to stay, or how much of it is a bubble or fad. It’ll be interesting to see.

Okay, so I went long on history and terminology and short on solutions for marketing and selling indie manga to English readers. I think others have tackled this well, but here are my final thoughts on finding readerships. Considering the two definitions of indie manga from the start of this column (the content itself is truly “independent” in nature and/or the English publisher that licensed it specializes in indie books), here are thoughts:

1) Branding the Japanese source of the books and harnessing that curatorial indie brand:

Manga fans know that GARO was an important publication and an easy parallel to make. But what about AX and COMIC BEAM as the place in Japan for the coolest shit? Top Shelf seems to be doing this well in the way they’ve framed their upcoming AX Anthology, and similar things are happening with the term ‘gekiga’ due to Drawn & Quarterly’s promotion of the genre/movement. The ’90s anthologies I love and cherish understood this too, positioning their collections as THE gateway (drug?) to a certain scene and era.

2) Accepting small audiences when they are and should be small for truly independent work, and finding lovers of the type of story that book tells.

As Peggy said in her email, they have success with Tatsumi because “we promote him as one of our D+Q cartoonists, and because we publish books for adults.” Here’s another interesting marketing example: the works of genius creator Naoki Urasawa are very much NOT indie — not in Japan and not in America. Yet Viz’s Signature line editor noticed in an interview that Pulitzer-winning author Junot Diaz had name-checked Monster in an interview in the mainstream press, and got him to write a blurb for the flap of Monster / 20th Century Boys . This is a coup in one sense, but does it sell books? How do you telegraph the indie/genre cred of comics from Japan?

________

The whole Komikusu roundtable is here.