Boots in Time

The first major touchstone in Fredric Jameson’s epic 1991 Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capital Capitalism is Van Gogh’s A Pair of Boots.

Jameson refers to this as “one of the canonical works of high modernism,” and goes on to argue:

that if this copiously reproduced image is not to sink to the level of sheer decoration, it requires us to reconstruct some initial situation out of which the finished work emerges. Unless that situation–which has vanished into the past–is somehow mentally restored, the painting will remain an inert object, a reified end product impossible to grasp as a symbolic act in its own right, as praxis and as production.

This last term suggests that one way of reconstructing the initial situation to which the work is somehow a response is by stressing the raw materials, the initial content, which it confronts and reworks, transforms, and appropriates. In Van Gogh that content, those initial raw materials, are, I will suggest, to be grasped simply as the whole object world of agricultural misery, of stark rural poverty, and the whole rudimentary human world of backbreaking peasant toil, a world reduced to its most brutal and menaced, primitive and marginalized state.

Fruit trees in this world are ancient and exhausted sticks coming out of poor soil; the people of the village are worn down to their skulls, caricatures of some ultimate grotesque typology of basic human feature types. How is it, then, that in Van Gogh such things as apple trees explode into a hallucinatory surface of color, while his village stereotypes are suddenly and garishly overlaid with hues of red and green? I will briefly suggest, in this first interpretative option, that the willed and violent transformation of a drab peasant object world into the most glorious materialization of pure color in oil paint is to be seen as a Utopian gesture, an act of compensation which ends up producing a whole new Utopian realm of the senses, or at least of that supreme sense-sight, the visual, the eye-which it now reconstitutes for us as a semiautonomous space in its own right, a part of some new division of labor in the body of capital, some new fragmentation of the emergent sensorium which replicates the specializations and divisions of capitalist life at the same time that it seeks in precisely such fragmentation a desperate Utopian compensation for them.

There is, to be sure, a second reading of Van Gogh which can hardly be ignored when we gaze at this particular painting, and that is Heidegger’s central analysis in Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes, which is organized around the idea that the work of art emerges within the gap between Earth and World, or what I would prefer to translate as the meaningless materiality of the body and nature and the meaning endowment of history and of the social. We will return to that particular gap or rift later on; suffice it here to recall some of the famous phrases that model the process whereby these henceforth illustrious peasant shoes slowly re-create about themselves the whole missing object world which was once their lived context. “In them;” says Heidegger, “there vibrates the silent call of the earth, its quiet gift of ripening corn and its enigmatic self-refusal in the fallow desolation of the wintry field.” “This equipment,” he goes on, “belongs to the earth, and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman. . . . Van Gogh’s painting is the disclosure of what the equipment, the pair of peasant shoes, is in truth. . . . This entity emerges into the unconcealment of its being;’ by way of the mediation of the work of art, which draws the whole absent world and earth into revelation around itself, along with the heavy tread of the peasant woman, the loneliness of the field path, the hut in the clearing, the worn and broken instruments of labor in the furrows and at the hearth Heidegger’s account needs to be completed by insistence on the renewed materiality of the work, on the transformation of one form of materiality–the earth itself and its paths and physical objects–into that other materiality of oil paint affirmed and foregrounded in its own right and for its own visual pleasures, but nonetheless it has a satisfying plausibility. At any rate, both readings may be described as hermeneutical, in the sense in which the work in its inert, objectal form is taken as a clue or symptom for some vaster reality which replaces it as its ultimate truth.

For Jameson, if the painting is not to be decoration, if it is to have meaning, then it needs to include meaning — which is to say, narrative, or history. The decoration, the burst of color, is merely a surface to be consumed unless it has a context attached to it. That context is both the past (the long path of the immiserated peasant through his life of toil, up to his door, and to the moment when he removes these, his boots); the present (especially in Jameson’s second reading, where the painting creates the peasant woman and the field and the earth around itself) and the future (as the burst of Utopian color, the yearning towards a decidedly material relief.) The painting calls for a story to complete it.

This is obviously a very Marxist reading. But it’s also a comics reading.

At first calling it a comics reading may seem a little startling, because there is often a very strong push in comics crit against ideological readings. Recently on this site, for example, Matthias Wivel argued:

Which brings me to the other issue I have with the critical reception of Habibi, and comics in general: the lack of sensitivity to how the visuals are integrally determinant of the work. Critics tend not to look beyond the surface qualities of the drawing in comics, and then proceed to discuss whatever conceptual issues are at stake without devoting much attention to how those issues are manifested visually. Even a cursory examination of the reviews published so far of Habibi should demonstrate this. Only a few have been entirely positive and several have been strongly negative in the conceptual assessment of the book and its ‘writing,’ but the majority of the reviewers have nevertheless taken time to commend the ‘art.’

Matthias argues that critics “tend not to look beyond the surface qualities of the drawing in comics” — which can not entirely finesse Jameson’s point that drawings are, literally, surface. Matthias goes on to a lengthy and thoughtful discussion of, among other things, Thompson’s line. But the discussion of that line itself seems flattened by Matthias’ circumspect refusal to give it a context. He criticizes Thompson for failing to convey complexity of emotion — but why exactly are we supposed to desire complexity of emotion? He points out the lack of spontaneity in Thompson’s line — but why does it matter if the line is spontaneous or not? Without the ideology that Matthias denigrates, the critique is left foundering in a thin (because untheorized or acknowledged) humanism or else, as Jameson suggests, in the even thinner realm of decoration, where the ink is appreciated in its inkness, a connosieur’s pleasure. (One could, of course, defend connosieurs and decoration — but I don’t know how you could go about doing that without wading into the deeper shoals of ideology.)

To be fair, Matthias isn’t calling for non-ideological readings; just ideological readings which pay more attention to surfaces. But (as is the way with such things) he ends up so chary of ideology that he seems to be paying attention just to the surface — looking so closely at the trees that the forest drops out of the peripheral vision. Jameson insists on looking beyond the image, on saying where it is coming from and where it is going to. For Van Gogh’s shoes to have meaning, they have to be in the world, affected by it and affecting it; they have to be made for walking. Matthias, in contrast, seems at times to want the line to draw a circle around itself, keeping the world, with its messy moral judgments and harumphing ideology at bay.

What’s strange about this tack is that it seems to miss the essence of comicness — to call for a focus on surface when sequential art has that “sequence” right there in its name. The comic book does exactly what Jameson does; it provides the situation for each image, and for each image the situation.

Comics in Jameson’s terms then seem to be what others have sometimes praised them for being; that is, resolutely committed to old-fashioned artistic values — a medium committed to Van Gogh rather than to Jameson’s post-modern exemplar, Andy Warhol:

Now we need to look at some shoes of a different kind, and it is pleasant to be able to draw for such an image on the recent work of the central figure in contemporary visual art. Andy Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes evidently no longer speaks to us with any of the immediacy of Var Gogh’s footgear; indeed, I am tempted to say that it does not really speak to us at all. Nothing in this painting organizes even a minimal place for the viewer, who confronts it at the turning of a museum corridor or gallery with all the contingency of some inexplicable natural object. Or the level of the content, we have to do with what are now far more clearly fetishes, in both the Freudian and the Marxian senses…. Here, however, we have a random collection of dead objects hanging together on the canvas like so many turnips, as shorn of their earlier life world as the pile of shoes left over from Auschwitz or the remainders and tokens of some incomprehensible and tragic fire in a packed dance hall. There is therefore in Warhol no way to complete the hermeneutic gesture and restore to these oddments that whole larger lived context of the dance hall or the ball, the world of jetset fashion or glamour magazines.

Yet this is even more paradoxical in the light of biographical information: Warhol began is artistic career as a commercial illustrator for shoe fashions and a designer of display windows in which various pumps and slippers figured prominently. Indeed, one is tempted to raise here–far too prematurely–one of the central issues about postmodernism itself and its possible political dimensions: Andy Warhol’s work in fact turns centrally around commodification, and the great billboard images of the Coca-Cola bottle or the Campbell’s soup can, which explicitly foreground the commodity fetishism of a transition to late capital, ought to be powerful and critical political statements. If they are not that, then one would surely want to know why, and one would want to begin to wonder a little more seriously about the possibilities of political or critical art in the postmodern period of late capital.

But there are some other significant differences between the high-modernist and the postmodernist moment, between the shoes of Van Gogh and the shoes of Andy Warhol, on which we must now very briefly dwell. The first and most evident is the emergence of a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality in the most literal sense, perhaps the supreme formal feature of all the postmodernisms to which we will have occasion to return in a number of other contexts.

Van Gogh’s shoes look like they’ve just been tossed aside by a perambulating peasant; Warhol’s look like they’ve been purchased new from some shop window and then hammered flat. No one has worn them, no one will wear them; they are shoeness without story. If they have an ideology or a narrative, it is the narrative of no ideology and the ideology of no narrative.

In contrast, consider this sequence from Hideo Azuma’s Disappearance Diary:

The worker’s shoe here is not abandoned as in Van Gogh; instead, it is in its place, on the foot of an actual worker, inside a narrative. The upper right panel, showing Azuma tying his own shoe, wraps itself in time, the hands creating a whirlpool of motion with the shoe an anchor at the center. If the shoe in Warhol is dead and the shoe in Van Gogh points to life, then this shoe is actually alive, tied up with time. Azuma is effectively pulling on the working class identity, with its manual facility and expertise (“this made me look cool like a veteran.”) There is no burst of color, and no utopian vision, but the motion lines and, indeed, the panel progression still energizes the images. The narrative is in the picture and the picture in the narrative; the boot is not just its surface, but, as with Van Gogh, its story.

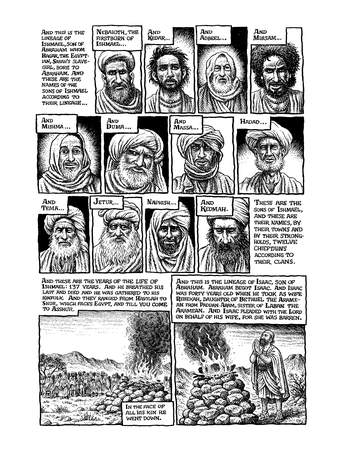

Comics then, can be seen less as an illustration of text than as a narrativizing of illustration — a form which pushes back against the shallowness of contemporary art practice by embracing the old-fashioned narrative and ideological virtues of prose. From this perspective, the achievement of R. Crumb’s Genesis is not giving flesh to every passage in the Bible, but rather giving narrative to every image. There are many, many Biblical paintings and drawings which show us Biblical characters as flesh and blood:

Crumb’s Genesis, however, is much more rare in insisting the the flesh of the Biblical image must be elaborated by the Biblical text itself. Crumb’s Bible is narrative; generations begatting through time, each with its own face that takes on weight only in relation to all the other faces.

In this sense, Crumb and comics themselves can perhaps be seen as analogous to doubting Thomas. Seeing is not enough; you also need the experience of narrative and the word. If post-modernism proffers the dehistoricized image, comics insists on reinscribing it. Backwards looking in every sense, comics does not exist without the preceding panel, the one that gives the present depth and meaning.

Boots in Space

In Postmodernism, Jameson specifically claims that the distinction between the modern and post-modern is in post-modernism’s spatialization of time.

A certain spatial turn has often seemed to offer one of the more productive ways of distinguishing post-modernism from modernism proper, whose experience of temporality — existential time along with deep memory — it is henceforth conventional to see as a dominant of the high modern.

Thus, Van Gogh’s shoes, imbued with a past and a future, become Warhol’s shows, shorn of history, existing as pure space. Or (though Jameson does not use this example specifically) the painful, crushing sense of a life passing in a stymied claustrophobia in Kafka’s parable of the man at the door of the law is replaced in Borges’ story “The Double” with a miraculous simultaneity, as an older Borges and a younger Borges suddenly exist in the same space, so that time becomes not an unavoidable weight but a sleight-of-hand juxtaposition. As Jameson says, “Different moments in historical or existential time are here simply filed in different places; the attempt to combine them even locally does not slide up and down a temporal scale…but jumps back and forth across a game board that we conceptualize in terms of distance.”

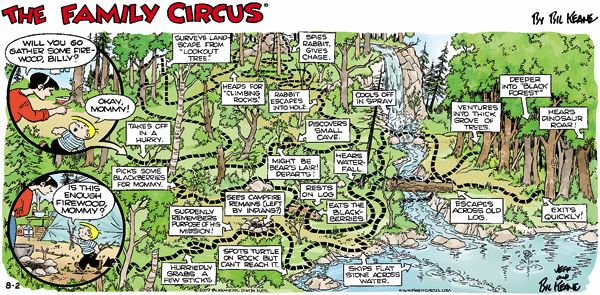

What would it look like if you turned time into space on a metaphorical gameboard? Maybe something like this?

The time of Billy’s journey is turned into a single schematic, a line which we can lightly trace. As Jameson says, different moments are simply filed in different places; the modernist pleasure of recuperation and depth is here replaced with the pleasures of surface and juxtaposition.

From this perspective, comics are not a backwards-looking modernist medium at all, but rather a post-modern engine for flattening time and narrative into space — of making time itself a manipulable, reified product. As an example, the Hideo Azuma boot-tying sequence:

Is the boot really energized and enriched by the narrative? Or does the existence of the narrative as spatial image allow time itself to become a mere decoration? The whipping hands and the boot so simplified it is almost a logo — Azuma presents this not so much as a specific boot in time, but as an iconic representation of a desirable skill, contained in a box and reproducible specifically for public consumption. Van Gogh’s boots were valuable for the life that had lived in them; Azuma’s are valuable because of their own image; they make him “look like a cool veteran.” Time — the working-class narrative of bootness — is flattened, mastered, and packaged for consumption. The boot points not to Marx’s utopian narrative, but to Lacan’s mirror stage; the exhilarating moment of mistaking a reflection for one’s past and one’s future.

You can similarly reinterpret Crumb’s Genesis.

Rather than using the narrative to give life to the image, the steady drumbeat of the images crushes the narrative. Generations are spread out across the page like moths pinned for display, or like collectable baseball cards. Narrative and ideology are systematized and controlled. The mystery of time becomes the fetish of space, patriarchs set together cheek by jowl with a repetitive obsessiveness reminiscent of Warhol himself.

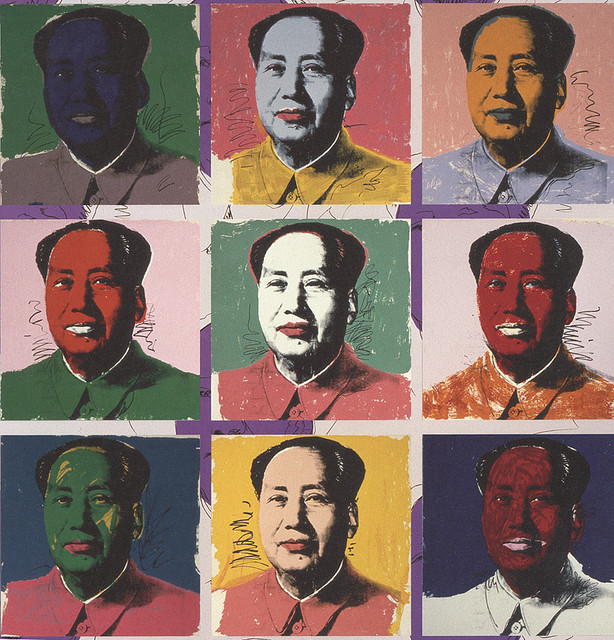

Warhol’s treatment of Mao is more explicitly parodic, but for that very reason it is almost more respectful. Mao and Mao’s image are, for Warhol, worth defacing and worth queering. Crumb’s Genesis, on the other hand, is treated as meaningless — one of the most consequent texts in history becomes a mere decoration, lines on paper. Ng Suat Tong’s is right that Crumb is “watering down” Genesis, but he’s wrong to think that this is a bug rather than a feature. If Crumb’s Genesis has a point, it is precisely the evacuation of content, the rendering of the Bible as merely another surface pleasure, its long history become a mere image no difference from any other that flickers across our optical nerves.

Jameson barely mentions comic book’s in Postmodernism; there’s one throw-away line in which he talks about post-modern bricolage as comic-book juxtaposition (and as schoolboy exercise.) In contrast, he devotes a great deal of time to video art, of which he says:

Now reference and reality disappear altogether and even meaning — the signified— is problematized. We are left with that pure and random play of signifiers that we call postmodernism, which no longer produces monumental works of the modernist type but ceaselessly reshuffles the fragments of preesistent texts, the building blocks of older cultural and social production, in some new and heightened bricolage: metabooks which cannibalize other books, metatexts which collate bits of other texts — such is the logic of postmodernism in general, which finds one of its strongest and most original, authentic forms in the new art of experimental video.

Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway

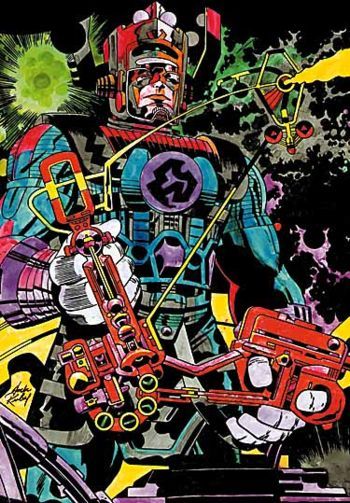

But if video art is the quintessential post-modern genre, perhaps it’s possible to see comic-books as its fuddy-duddy dialectical twin. Where video art fragments, comics reify. Where video art erases, comics embalm. Where video art heightens the ADD of advertisement, comics channels advertising’s depthless, deathless monomania.

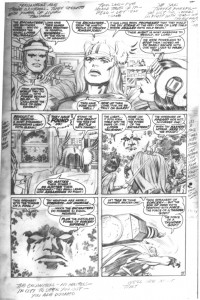

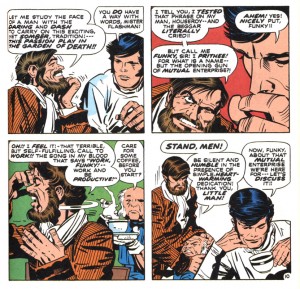

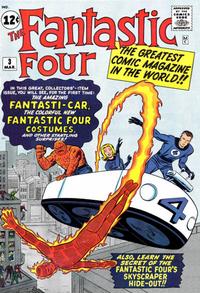

Stan Lee/Jack Kirby “Save Me From the Weed!”

Stan Lee’s advertising huckster sloganeering (“A weed the likes of which the world has never known!”) is the perfect soundtrack for a medium in which time passing is shown by compulsive iconic repetition. Kirby’s helplessly neotonic weed, straining virilely against its roots, is a pre-Internet self-contained viral meme, its image replicating across the page like an embedded video or Warhol’s fecund Maos. Video art fractures identity into a unassimilable riot of images; comics turns repetitive image into identity. The evil weed next to the evil weed next to the evil weed might as well be a series of toys each in its box on the shelf in Wal-Mart, every iteration a pitch for all the others.

Comics’ crass refusal of the past as history, its suffocating nostalgia for and commodification of even the most dunder-headed images simply because they are images, can be a depressing spectacle. Yet, if comics epitomizes some of the worst excesses of the zeitgeist, is that not a sign of its relevance? As Jameson notes, there is no getting outside post-modernism; to the extent that we have a narrative, it is our narrative; to the extent we have a surface, it is our surface. We can mourn the rich texture and context of Van Gogh, but our mourning is itself post-modern, a loss based in our position after the modern has gone. If we pick up Van Gogh’s shoes again:

to illustrate a point or create a narrative, then those shoes become ours, not his. They lose their lodging in the past and find a space in the present, digitally replicated ad infinitum, almost like a comic book.