A few weeks back I reposted an essay on superhero and fascism. Somewhat to my surprise, it generated more than 150 comments, mostly from folks skeptical about my thesis.

A few weeks back I reposted an essay on superhero and fascism. Somewhat to my surprise, it generated more than 150 comments, mostly from folks skeptical about my thesis.

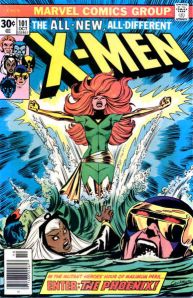

That thesis was, to recap quickly, that superhero narratives are about fascism. That isn’t to say that superheroes are always fascist. On the contrary, there are a lot of superhero stories, like Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, or Grant Morrison’s Animal Man, or the Marston/Peter Wonder Woman, or Watchmen, which consciously work against the superhero-as-fascist trope, offering some combination of parody and critique. Those parodies and critiques go back to the beginning of the genre, just about. And, for that matter, Superman himself is a response to fascism, a kind of New Deal mirror image of the Nietzschean Nazi Superman, both embodiment and critique.

With that in mind, it’s maybe interesting to look at fascism in light of another typical male action hero narrative that is not a superhero story. In particular, Stephen King’s Running Man.

Running Man is a dystopic near-future reality show adventure from way back in 1982, long before Battle Royal or the Hunger Games (or the reality television craze, for that matter.) The story is set in 2025, and our hero, Ben Richards, is part of the mass of impoverished peons living in environmentally degraded inner cities. He’s out of work; his little girl is deathly ill with pneumonia, his wife turns tricks to try to get her crappy, black market medicine. In desperation, Richards decides to compete on one of the deadly reality television shows where proles are paid to get abused and killed for the entertainment of the masses. Richards ends up on the highest rated show, the Running Man, where he essentially becomes a fugitive, with the entire apparatus of the state hunting him down for a mass audience.

In a lot of ways, Richards is not unlike Batman or Daredevil, or any of a number of scrappy, ground level low-power superheroes. He’s extremely resourceful, cunning, and deadly, a master of both disguise and improvised violence. The scene where he rigs an explosion in the basement of the YMCA, killing at least five cops before making his escape through a sewer pipe, is reminiscent of Rorschach’s deadly fight with police involving kitchen products and a spear gun. (I wouldn’t be surprised if Moore had read The Running Man, though I doubt it was a direct influence.)

The surface similarities, though, just emphasize the differences. Rorschach fights the cops because his fight against crime is illegal — but he never actually tries to, or thinks about, fighting the cops because the system is corrupt. Superheroes fight bad guys; cops may be collateral damage, but the enemy is the criminals, not the state. The one hero who does launch an attack on the powers that be is Veidt — and in so doing, he demonstrates that he’s a (ironized, complicated, but still) super-villain.

In The Running Man, on the other hand, the state is the bad guy. Whereas in Watchmen, or in any random Bat-or Spider-title, the proliferating evidence of evil and corruption are low level street punks and thugs, in the Running Man the minions are the cops, who glower and lurk around every page, fat, dumb, menacing and dangerous, the toughest street gang around. The dastardly supervillains with their fiendish plots are the guys in suits, the executives and government manipulators who have let industrial by-products turn the air into a carcinogen and then refuse to distribute filters to the poor. Rorschach, or Batman, or Spider-man, fight for decency and justice, but in Richards’ world, decency and justice are just a ruse or brutality. “If you’re so decent,” as Richards says to a woman he kidnaps, “how come you have six thousand New Dollars to buy this fancy car while my little girl dies of the flu?”

You could argue that Richards is not a superhero because he doesn’t have superpowers or a costume or a secret identity. But all of those aspects of superherodom are really more or less optiona. What really makes Richards not a superhero is that he’s neither a fascist nor really troping against fascism. Heroes in this world don’t have the power. The guys with the power are villains.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying that The Running Man, by virtue of separating power and goodness, is more moral than superhero narratives. In the midst of our perpetual recession, The Running Man does seem almost eerily relevant, but that doesn’t necessarily make Richards, or the novel, especially admirable. Just for starters, the book treats the injustice it documents as a crisis of masculinity; poverty has emasculated Richards, and the violence he perpetrates during the game is an extended demonstration that he’s retrieved his bits. In one particularly unpleasant scene, he undergoes psychological testing by a woman in improbably revealing clothing, and demonstrates what a bad ass he is by leering at her and then patting her rear. When she tearfully tells him he’ll get in trouble, he responds that she’ll lose her job if she reports him. Why she would isn’t very clear, but such logical hurdles are less important than making sure Richards can assert his manliness through the tried and true method of sexual harassment.

And if garden-variety misogyny isn’t enough for you, there’s the book’s denoument, in which Rogers flies a plane into the giant skyscraper housing the government bureaucracy that controls the games. King wrote this 20 years before 9/11, but looking back now from that vantage, it seems like an eerily precognitive endorsement of the attacks. Marginalized people with nothing to lose destroy the towering symbol of their oppression. It feels a lot less celebratory when you’ve had a chance to actually count the dead.

As this suggests, Running Man is as violent, or more violent, than most supehero narratives — but the violence is the violence of revolution, not law and order. Richards isn’t a glorified cop; he’s a glorified criminal. And not one of those patented superhero mistaken-for-a-criminal-but-still-fighting-for-order kind of things, a la Miller’s Daredevil or Dark Knight.

There is actually a moment towards the end of the book where Richards thinks about becoming a cop. He’s been so successful at the game that the powers that be offer to make him the chief Hunter; the head of the evil bastards who track down the running men. He’d be an uber-cop — or,if you will, a superhero. Maybe, then, Running Man is a kind of superhero narrative after all, at least in the sense that fascism, or superheroism, trail Richards like a shadow, both inescapable oppressor and dark double.