W.A.S.P. Thanksgiving

Redneck Thanksgiving

Animated Thanksgiving Continue reading

Bliss was it to be alive in that dawn,

But to be young was very heaven!

—Wordsworth

A house in Launceston Place, Kensington, London; we were a couple of doors down.

In 1969, my family moved to London; in December of that year, I turned 15.

London– 1969– 15 years old?

Yesss!!!!

“Swinging London” was still very much roaring along. Behold Carnaby Street, luv:

I’d come from a deeply repressive Swiss all-boy Jesuit school the year before, where tracts against masturbation were solemnly handed out, and attending a party featuring ‘impure’ pop music was grounds for expulsion.

And here– just in time for my puberty– was I introduced to this carnival, this opportunity to blossom!

Soon I’d ditched my staid flannel tartans and chino trousers for paisley scarves, ruffled pink shirts, and bell-bottom pants…

That’s me, age sixteen, literally rising above my peers at school.

The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix (who died in the hospital next door to our first house — for some reason that spooked me at the time), The Mothers of Invention, The Rolling Stones…they furnished the soundtrack to my life.

Ah, but this is a column about comics, is it not? So what was the scene like at the dawn of the ’70s?

It was glorious.

Current wisdom holds that comics of the ’70’s were in a particularly dire patch of their history; but this sad state of affairs came about essentially after 1973, and there were bright spots even so until the end of the decade.

The comics Underground was at the apex of its short history; Crumb, Shelton, Deitch and co. Their comics were hard, but not impossible, to find in London; generally in the funkier record shops like Cheapo Cheapo Records off Picadilly, or in the patchouli-scented head shops.

Mostly, though, they were reprinted in underground newspapers like the International Times (IT):

click image to enlarge

The British Underground comics scene was pretty underdeveloped, though there were promising exceptions. Here, from IT, is Michael Moorcock‘s Jerry Cornelius, as rendered by Mal Dean:

click image to enlarge

An all-comics offshoot of IT was Nasty Tales, edited by the musician Mick Farren. More Crumb than you can shake a stick at:

… and it was a Crumb spread of an orgy that caused the publisher to be prosecuted in the sensationalised trial that set a precedent for freedom of the press. A benefit comic was published, with early work by Dave Gibbon:

Meanwhile, across the Channel, French comics were enjoying something of a golden age; magazines such as Pilote and Charlie were moving to more adult content.

That 1969 Christmas, my father gave me a book that was a touchstone for an entire generation of fans: The Penguin Book of Comics, by George Perry and Alan Aldridge:

My collecting centered mostly on the American mainstream: Marvel, DC, Warren.

At first, American comics were distributed in the UK in a very haphazard manner.

They were mostly unsold copies from the USA that were shipped across the Atlantic as ballast. You never knew what you’d find: that ensured the thrill of the hunt all collectors know.

It was a rich period in the mainstream. The old-guard cartoonists– Kirby, Adams,Wood, Severin, Kubert, Heath, Kane and so on– were at the top of their powers, and were joined by a crew of young Turks of remarkable talent– Barry Smith, Mike Kaluta, Berni Wrightson, Frank Brunner, Ralph Reese, Howard Chaykin.

Popular genres other than the super-hero were still flourishing: war, mystery/horror, romance, fantasy. There was still a plethora of humor books.

And an innovation that foretold the future of comics as we know it was coming into being: the comics shop.

click image to enlarge

When I first opened the door of ‘Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed’, Britain’s first comics store, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. A shop given over entirely to comics? Was it possible? Was it even legal? It was indeed.

Derek ‘Bram’ Stokes and Diane Lister…for ten years the priests of London’s comics temple

And for the first time, I was meeting other comics lovers there: I had discovered fandom. And with fandom, fan publishing.

In those pre-Internet days the main medium of communication for comics lovers was the fanzine. Britain had its fair share of ‘zines, such as Rich Burton’s Comic Media News or Frank Dobson’s and Dez Skinn’s Fantasy Advertiser.

Yes, breathes there a fan with soul so dead that to himself has never said, ‘I think I’ll start a little fanzine’?

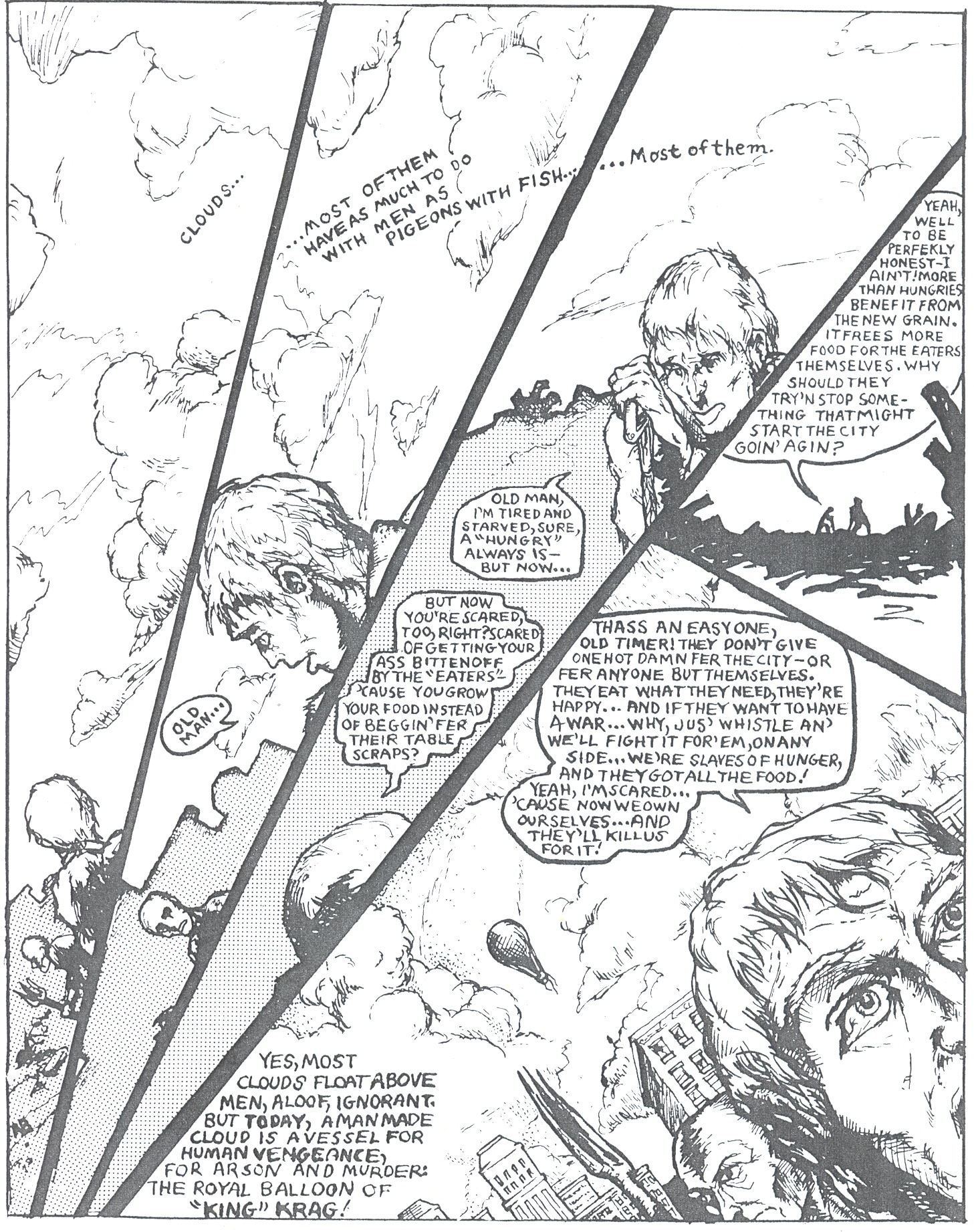

And indeed that was my thinking when, aged sixteen, I started drawing a comic strip with the alliterative title ‘King Krag.’

Now, printing options were fairly limited in those days. Mimeograph was still widespread; photocopies were becoming available, but they couldn’t reproduce solid blacks and needed a special paper. Offset printing was expensive.

This last limitation, though, was swept away by a new business model. The Instantprint chain offered printing in small runs at a reasonable price. Not free, though, and I struggled to get together the twenty-five pounds needed for a print run of 200 fifteen-page pamphlets.

I took a decision that I regretted deeply at the time: I sold most of my comics collection.

In retrospect, I’m very glad I did. It broke the anally-retentive hold collecting had on me: thenceforth I would buy to read only. I would no longer obsess about completing runs of series and throw away money on stuff I didn’t even like to close gaps in my collection.

I teamed up with my friend Ahmed Sehrawry, who took the impressive title of Managing Editor; really, I just wanted someone to talk to– I did all the actual work. Another friend, Chris Lomax, provided the strange back-up strip ‘Milkman.’

I drew the strip same-sized (A5). Never again. You don’t save any time. In fact, the six pages took me over a year to finish.

I remember bringing the package of printed pages back to my school — the French Lycée in London — to the art department, where my art teacher gave me a room and a bunch of tables: yes, we were collating and stapling by hand– we couldn’t afford machine collation or binding. No worries, my friends and I had a good time; a collation party is much like a corn-shucking bee, an undemanding communal activity, interrupted by the odd tea break.

(Tea is one addiction I picked up in England.)

By God, the first time you see your work in mass reproduction is a trip and a half! And the first copy of a finished work…does that feel good in your hands.

I was seventeen and a publisher.

Now, I will beg your indulgence for the artwork shown. It was produced by an immature young fellow who wore his influences all too prominently; I’m harder on that boy than you could ever be. Still, as an artifact of a past 38 years gone, it repays arm-length study. Here is the cover of Bizarro #1:

What strikes the 55-year-old me about the seventeen-year-old me’s drawing above is the level of violence. True, the culture was moving that way; this was the age of films like The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs and A Clockwork Orange. But looking at that cover, I can only ask in dismay: was I that full of incoherent rage? More than another typical teenager? Apparently, yes.

Influences are embarrassingly obvious: Frank Frazetta, Barry Smith. A less obvious influence is Géricault‘s Le Radeau de la Méduse:

…which explains why so many of the figures therein rudely turn their back on the reader.

Also irritating are the visual tics picked up from Berni Wrightson: the ‘saliva ropes’ in the shouting character’s mouth, the ‘twisty hair’ on his forearms.

Note the patterned background: I had just discovered Letratone, and like so many neophytes was inclined to abuse it, as the luckless readers of this blog shall soon confirm.

On the plus side, the composition holds together fairly well (you can’t go far wrong with triangles) and there’s a real sense of depth.

But that sloppy logo is unforgiveable.

On to the strip. It’s a nightmare of incompetence.

Note on this splash page how I avoided heavy blacks: at that time, I was intending to produce this via photocopy.

Apparently, in the year 2025, for some reason they revived flintlock muskets…

It’s the standard post-apocalyptic fun future, inspired by Roger Zelazney‘s novel Damnation Alley and, oddly, Jack Kirby’s early Jimmy Olson comics. A bit over-tidy for after the apocalypse

I’m surprised to see how competent the perspective is: I don’t recall having studied perspective at that age (16), but I guess I had.

I’m afraid lousy dialogue and worse lettering are the hallmarks of my writing here. I was a nice white middle-class boy, so of course I tried to talk tough. Guns are by definition cool at that age.

Not the fishbowl-lens perspective on the guy’s hand in panel two. I was probably imitating Neal Adams.

The fussy, unnecessarily confusing odd panel shape was a disease of the time. I guess I was following in the footsteps of Jim Steranko and of Neal Adams. Note the last panel: you won’t see another woman in this macho world for macho men.

More weird layouts, odd angles, arbitrary cropping. The guy walking downstairs looks like he’s about to fall on his hairy face. I learnt that the real challenge in drawing isn’t in detailing giant space armadas– it’s in showing someone walking downstairs or opening a door.

So endeth chapter one.

There followed a mimeographed page of messages from the editor. I’m relieved to note that neither Ahmed nor I took himself very seriously. It was typewritten: word processors didn’t exist, and typesetting was expensive.

Rounding out the book was Chris Lomax’s ‘Milkman’. Its primitivism and absurdity have stood the test of time better than my overblown strip. Chris went on to be a successful stage and set designer in Paris, working on films such as Betty Blue.

We return to the horrors of mimeograph. Bram at ‘Dark they Were and Golden-Eyed’ let us drop off some copies on consignment if we’d run a free ad for his shop.

Well, Bram, you get what you pay for. And this is what ‘free’ pays for:

Ahmed took fifty copies to sell at his school; I took the remaining hundred and fifty to sell in mine. I recruited my brothers Philippe and Gérard, as well as friends like fellow comics- fan Sanjit, to spread out through the school and tout my inky baby.

We sold out within 24 hours.

It seems that publishing a comic in high school is like giving a rock concert in the gym or acting in the school play. The kids’ll support you just because you’re one of them. (Our principal was something of an arsehole about it, as I hadn’t asked for his permission; fuggim, I was out of there anyway.)

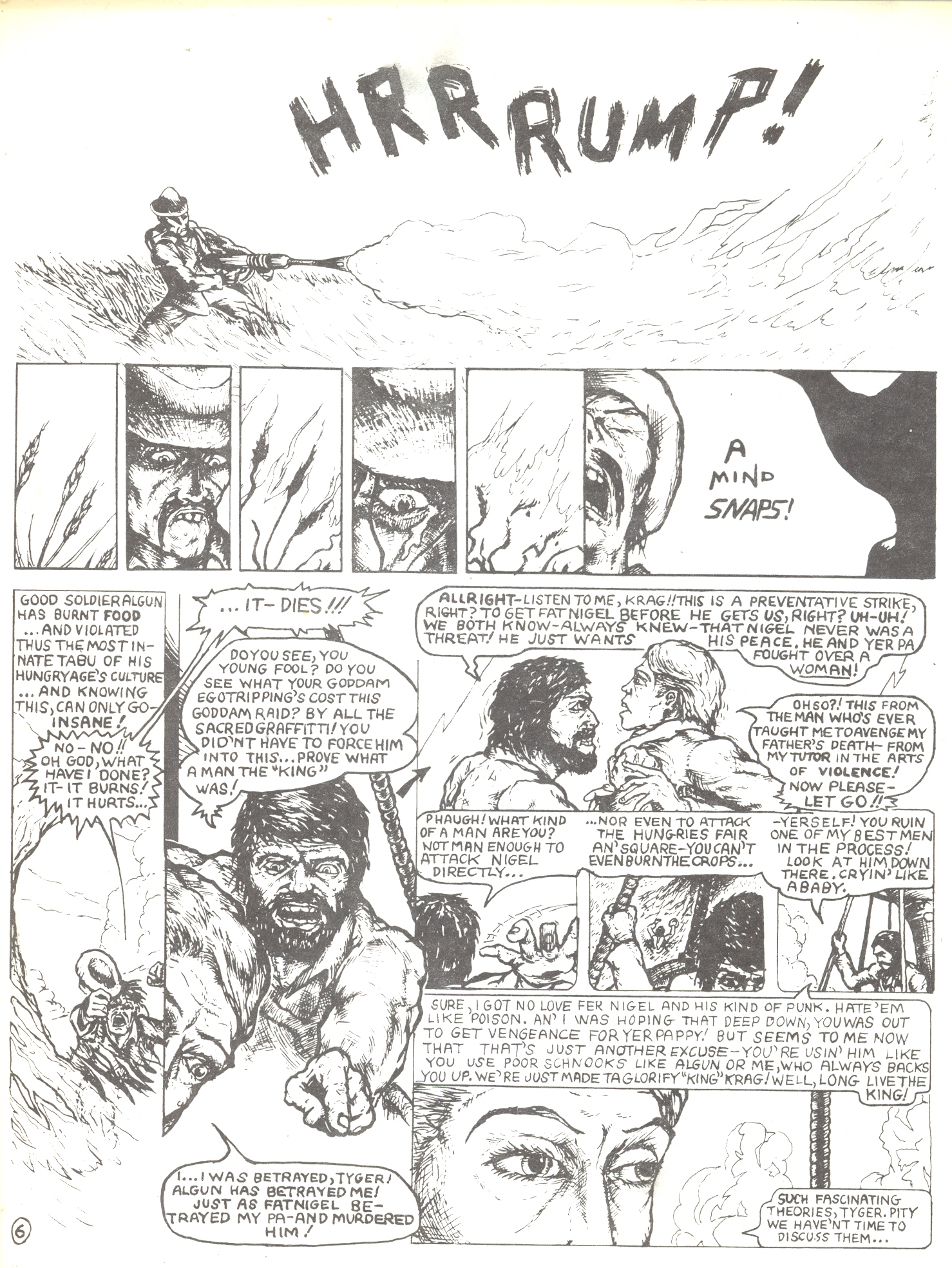

Issue 2 came out over a year and a half later. Now I’m a terribly slow artist, but this was ridiculous.

I had gone to Paris to study art at the Faculté des Arts Plastiques et des Sciences de l’Art of the Sorbonne. I was studying electro-acoustic music under Yannis Xenakis, screenwriting under Eric Rohmer, conceptual art under Journiac, comics under Jean-Claude Mézières.

I had outgrown my adolescent strip. It frankly embarrassed me.

Why didn’t I just give it up, then? A misplaced puritanism– I had vowed to break my bad habit of starting projects and not ending them; and I didn’t want to let Ahmed down.

The second issue boasted another odd cover, replete with clichés taken from Frazetta, Ploog, and Gustave Doré. I like the poor sap in the foreground’s expression. “I gotta turn around…but I really don’t wanna turn around…but I gotta…”:

Page one– more arbitrary panel noodling, fatuous captions, and peasants dutifully giving us an “infodump”: a massive exposition of stuff they already know and shouldn’t be repeating.

God, the inflation of those speech balloons.

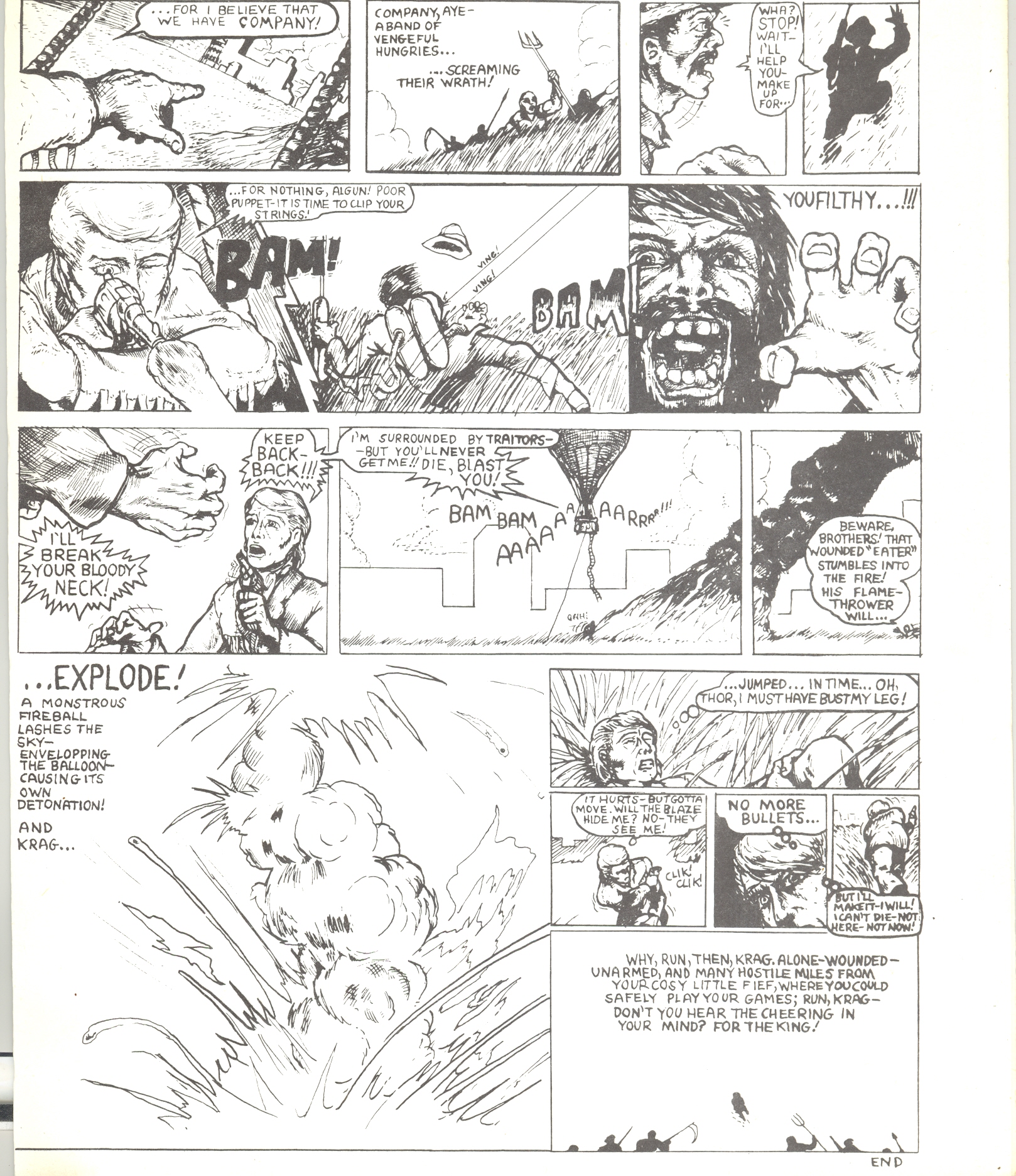

More gratuitous violence follows. (I give myself some credit for actually researching hot-air balloons.)

From here to the end, you’ll note that the panel-per-page ratio goes up, to as much as fifteen. Was this innovative structuring for more intense beats? No, it was bad planning. I leave the rest of the story to the masochistic blogreader. It depresses me to read it myself.

For the second issue I had simply mailed the pages to Ahmed in London and let him do it all himself. A bit cowardly of me.

Ahmed found a 15-year-old artist named Marcelo Anciano to fill out the rest of the book:

When I finally met Marcelo the next summer, I remarked how his characters’ weapons were such blatant phallic symbols (see above). He nearly died laughing.

(Marcelo is now a film director and producer, working with Quentin Tarantino and other luminaries.)

Note in Marcelo’s back cover how he spells ‘Bizzaro’ for ‘Bizarro’. We were all over quality control, weren’t we?

The second issue was a sales disaster, as it probably deserved to be. I didn’t care; I’d purposefully disengaged myself from it, which was unfair and a betrayal to Ahmed and to Marcelo.

Today, Ahmed is known as Ahmed Shawki, the editor of the International Socialist Review. I wonder if our failed little business venture soured him on capitalism? He’s certainly grown since this first foray in the publishing business.

(One 13-year-old fan, an architect’s son, who used to come to Ahmed’s place where we’d discuss comics, was definitely not a business failure. He went on to found the Forbidden Planet chain of bookstores, the dominant direct-market distributor in Britain, and Titan Books. His name was Nick Landau.)

For years after, though, I’d take copies of issue 2 to the comics marts off Tottenham Court Road and vainly try to flog’em. This led to an embarrassing incident (and a good lesson.)

After one mart in 1975 I was hanging around while the organisers dismantled the set-up. A fellow dropped by the table where I sat and asked to see some of my purchases; we got to talking. It was Dave Gibbons, then known to me as a very prolific fan artist. He said he was working on superhero comics for an African publisher and was about to do ‘Dan Dare’ for an upcoming IPC mag called 2000 AD.

I passed him a copy of my issue 2 and awaited his opinion.

Now, Mr Gibbons is a gentleman, and I’m sure he didn’t wish to hurt my feelings. He pointed to one panel and said: “I like this one”:

As it happens, that panel is the only swipe I’ve ever done– stolen from Swamp Thing # 4.

” God sees the truth, but waits” goes the old Russian proverb.

So does Dave Gibbons! I’ve never swiped a drawing since. Never.

(“What, never?”

“No, never!”

“What, neverrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr….?”

“Well…

…hardly everrrrrrrrrrrrrrr…!!!

1973 was a watershed year for comics. And not in a good way.

The Underground smashed into a brick wall: anti-obscenity Supreme Court decisions, anti-paraphernalia laws that destroyed headshops, a general change in the culture away from perceived ‘hippie dippie’ values, all nearly killed this once-vibrant sector.

The great paper shortage of 1973 and the oil embargo of that same year put crippling pressure on the mainstream comics companies.

They also were losing quickly their traditional retail outlets, and the nascent direct market wasn’t yet strong enough to take up the slack.

Britain headed into a decade-long economic slump, putting paid to ‘swinging London’ (and birthing Punk.) ‘Dark they Were and Golden-Eyed’ went out of business in 1981.

promotional button by Hunt Emerson

Still, in those old crude fanzines of Britain’s early seventies are the seeds of future accomplishment. It was here that the young Dave Gibbons, Brian Bolland, Kevin O’Neill and so many others took their first stumbling steps.

Bram, Diane, Rob, Des– I just want you to know that the whiny, loud, obnoxious fanboy 15-year-old you knew as Alex is now a whiny, loud, obnoxious fanboy 56-year-old, and he’d like to buy you all a jar so we can lament how comics have gone to the dogs since our day. ‘When I were a lad…”

As for me, I never published again, and remain a dilettante in comics. Looking back, I regret that I didn’t pursue an entirely different talent I had for caricature; it would’ve borne more interesting fruit.

Ah, nostalgia just ain’t what it used to be…mais où sont les neiges d’antan? Where are the snows of yesteryear?

Below is a recent bit of foolery, done for an online ‘exquisite corpse’ jam comic:

That’s about the limit for me nowadays.

Yet, hard as I’ve been on my adolescent self — still I’d give up everything I have to relive those days, those golden years gone forever, when I was teenage cartoonist.

****************************************************************************************************

For a good overview of the British fanzine movement, check out

Dez Skinn’s entertaining take.

An incredible resource:

the International Times archive.

Lastly, that jam I contributed to:

Good fun, check it out

But he took the wee baby seal by the flipper. “You little rascal!” he said. “You’ll grow up some day to be a big seal and then you’ll destroy my net if I’m still here.” And he took the wee baby seal, hit its head against a rock, and threw it among the seaweed on the shore. —The Silkie’s Revenge

The pleasure of a library sale is that of a second-hand bookshop – the pleasure of serendipity, of finding what was unlooked-for. Thus I never miss any that are held at my beloved American Library in Paris.

“Come oot,” he said, “I want to show you something!” “What is it?” she said.

“Come here, come here. I want to show you something! Look!” he said to his wife. He opened the door of the byreand he showed her — there was the cow and there was the bonnie wee calf standing at her feet, there was the pail of water and there was the hay in her wee heck at her nose, and the cow was as healthy as could be and so was the calf! —The Broonie on Carra

At last month’s sale, I took in my haul the following wee book, paid for at the price of 1 euro– one of the better purchases I have made as a collector:

The Broonie, Silkies and Fairies is a collection of traditional oral tales from the travellers of western Scotland, a folk of nomads like the tinkers of Ireland or the Rom/ Gypsies, as told by traveller Duncan Williamson (1928–2007).

“I was reared, born and bred on stories. That’s all I had in my life.”– Duncan Williamson

Every day she used to go hawking with the old woman too, selling her basket and tinware to the houses.

So one day she says, “Mother, dae ye never get fed up on the sea? Dae yese never go on the roads?”– Saltie the Silkie

From Williamson’s obituary in The Guardian:

Duncan was born in a tent on the banks of Loch Fyne, near Furnace in Argyll, the seventh of 16 children. Neither parent could read or write, but pipers, singers and storytellers on both sides of the family were testament to a rich oral culture. His father, a basketmaker and tinsmith, was determined that his children should get a basic education, and Duncan went to school in Furnace until, at 14, he was apprenticed to a stonemason and drystone-dyker, Neil MacCallum, who told him stories in English mixed up with words and phrases in Gaelic. A year later, he left home with an older brother, travelling all over Argyll and Perth. He worked as a farm labourer and became a horse dealer.

Duncan first heard stories and songs within the family, including a version of the classic supernatural ballad, Tam Lin, from his grandmother, Bet McColl. Duncan recalled his father’s storytelling in the introduction to his own collection of stories, Fireside Tales of the Traveller Children (1983). He knew his father was telling him something that “was going to stand us through our entire life”, and even though they may have had no food to eat, “we were full of love of our father’s voice”. He also recalled listening, at the age of 24, to an old man telling stories from 10 o’clock at night through to six the next morning. Such was the power of the storytelling culture of the Travellers. — Derik Schofield

It looked up and shook its fist. “Ye finally found the answer, but” it said, “many’s the night when I lay in your bosom and cuddled ye, I cuid have done terrible things to you– curse upon you! And curse upon your old postman!” Like that– he was gone. Gone, disappeared for evermore. — The Taen-Away

In the sixties, Williamson was discovered by folklorists, who recorded his tales for Edinburgh University; transcriptions of these stories were compiled into a series of books, such as the present one; it was published in 1985 by Canongate Publishing Limited, of Edinburgh, Scotland.

And the wee son used to say, “Daddy, why is it when you come to the bridge that you always push the pony past? I’d like to see the bridge and I’d like to see the river, I would like to see the steps going to the pool.’

“Son”, he said, ‘wheesht! You don’t know what I know… the Broonie lives in there! And these are his steps, he is in that pool — that’s why I hurry the horse past them.” — Torquil Glen

( The above drawing was printed upside-down in my copy!) These are tales of the supernatural– of fairies and the shape-shifting seal-folk, the Silkies; of changelings and sea-monsters; of the Broonie, the magical creature that rewards the generous and punishes the miserly.

I had no time for breakfast, I was so sad. I said, “Prob’ly she went out swimming and she got drowned.” And I was so upset, I didn’t know what to do. I searched the island, I went down the steps, searched the lighthouse outside and inside. She was gone, there was no Rona. — The Lighthouse Keeper

However delightful the tales, though, my purchase was prompted by the charming illustrations of Scottish illustrator Alan B. Herriot. And no small part of that charm is owed to Herriot’s masterful use of a now all-too rare illustrative technique: silhouette drawing.

And the King stood before Archie. “Archie, I’m sorry. You’ll hev tae move away from here.”

And Archie said, “Why should I move away from here?”

“Well,” he said, “you can move or you don’t need to, because we are gaunnae have a party here.”

And Archie said, “Who are youse?”

He said,”Archie, you ought to know who we are! Archie, we are the Little People, we’re the fairies! This is the day we’re going to have wir party here!” — Archie and the Little People

Nowadays, Alan Herriot is primarily a painter and sculptor in a naturalistic vein, author of several public monument statues.

Alan Herriot (right) in his studio

Worthy though these projects may be, one regrets the loss of the lightness and mystery, of boldness allied to delicacy, these illustrations from his youth so beguilingly set forth. Look again at the drawing of Archie and the Little People. The silhouette technique ‘sells’ the magic; by withholding visual information, the artist teases– and awakens– our imagination.

She said, “Auld man, my husband says ye’re hungry”

“Yes, my dear, I’m hungry.”

“Well,” she said, “would ye accept this bowl o’ soup?” —The Broonie’s Curse

Silhouette art goes back to the origins of human kind; it was found in the ten-thousand-year-old cave paintings of Lascaux; it was prominent in the murals of Pharoah’s Egypt; it reached a high degree of perfection in ancient Greek pottery. But its true apex came in the 18th century, when it was the commonest form of portraiture– as seen in the example below:

…occasionally involving quite complex group compositions :

This ascendancy declined in the 19th century with the coming of photography– although silhouette portraits by no means disappeared; below is depicted the poet Longfellow, by August Edouart:

And even today, silhouette portraitists ply their craft on seaside docks and at country fairs.

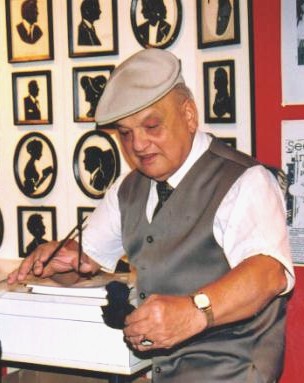

John Ross, a sihouette artist who employs the traditional technique of paper cut-outs

The silhouette has also been much used in the performing arts, whether in the Wayang puppet theatres of Java and Bali:

(French-language documentary and demonstration of Javanese Wayang) video here.)

…or in the cinema, as in the animated films of Lotte Reininger; this still is from her Adventures of Prince Ahmed:

Here is a video extract from ‘Prince Ahmed’

And this man said, “You have come here to stone the seals– we are the seal-folk and you have come here tae destroy hus. Ye meant…everything ye intend tae do is upon hus. So we cam here tonight tae do the same thing tae you.”–The Fisherman and his Sons

Illustrators have always prized the delicate possibilities offered by the silhouette, with work by Aubrey Beardsley and Edmond Dulac among the choicest; here are two illustrations to Cinderella by the mighty Arthur Rackham–(thanks to Noah Berlatsky for supplying them):

Today, this tradition is carried on by artists such as the witty Kara Walker:

In the press, silhouette vignettes were a useful design element in layout, for vignettes and colophons and headers; and examples can still be found in today’s New Yorker.

“Ye’re washin yir feet?” said the fisherman.

“Yes,” said the tramp, “I’m washin my feet. Because the day is hot.” — The Tramp and the Boots

In comics, silhouette work is generally punctual– to show a character is in the dark:

Christophe, ‘La Famille Fenouillard au Japon’, 1893 (click to enlarge)

…or as a simple way to vary panels:

Wallace Wood, ’22 Panels that always Work’: a guide for his assistants

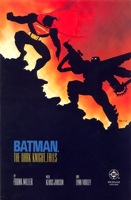

…or as a dramatic graphic device, as widely employed by Frank Miller:

Do we need more than this to know that Superman fights Batman?

Silhouettes, which deliberately withhold visual information, work well with visually stereotyped images of the type superheroes provide. An interesting use of silhouettes was pioneered in the obscure DC comic Strange Sports Stories: they made excellently speedy transition panels:

It is a pity the sihouette is not used more, as its aesthetic is well compatible with that of cartooning; to my knowledge, the only contemporary cartoonist who regularly uses silhouettes in continuity is Stéphane Blanquet:

From Blanquet’s ‘La Vénéneuse aux deux éperons’

I would be grateful for any others the reader can point out to me.

He walked down to the beach, there she was sitting and about fifteen or sixteen seals were all gathered round her. He rushed down to the shore and caught her by the arm, he dragged her back to the house. — The Crofter’s Mistake

I love the use of negative space in the above drawing.

“And remember: some day this farm will pass on tae you but promise me, as long as you own this place ye’ll never part with those breeches, or that coat or thae hose!”

“No, Daddy,” he said, “I never will.” — The Broonie’s Farewell

Duncan Williamson:

All my stories I’ve told you these past years belong to dead people– they’re all gone. And that’s why I want to tell them to you and to the world, because some day I’m not going to be around and I want people to remember and enjoy the stories that were passed down from generations of people, from the West Coast to Aberdeenshire, through Angus to Perthshire, down into Ayrshire, around the Borders, and all over– these beautiful stories that were not written down. All these stories are a matter of teaching, to show what can happen to you if you are evil and bad or good and kind. Because the travellers have met with so much badness, so much opposition and persecution along the way in their lives, even the thought of badness in their minds disturbs them. They believe that nobody in the world has any reason to be bad. They never hurt anybody. They live their own lives, do their own things and want to be left alone — like the seals.

As of October 2010, over 3000 travellers — ‘gens du voyage’ — have been deported from France…

Extracts from The Broonie, Silkie and Fairies copyright the estate of Duncan Williamson

Illustrations for The Broonie, Silkie and Fairies copyright Alan Herriot

Alan Herriot’s Website. Duncan Williamson’s obituary from the Independent.

Two beautiful silhouette animations by Lotte Reininger:

The Little Chimney Sweep

Cinderella

They are well worth a wee peek , lassies and laddies.

Finally, the gifted young artist and cartoonist Eroyn Franklin deserves a look. Mark how she uses reverse silhouettes (I.E. white-on-black rather than black-on-white). Thanks to Sean Michael Robinson for finding her.

In the two previous parts of this essay, we surveyed the intersection of comics and architecture in a one-sided way: showing how comics draw on architecture.

But what do comics have to offer architecture in return?

In conjunction with the Archi et BD exhibition reviewed in part 1, several architects were asked about their relationship to comics.

Francis Rambert and Jean-Marc Thevenet , curators of the exhibition

David Trottin, co-founder of the Peripheriques architectural collective:

“Many are the architects who have been marked by Gotham City and all those American cities you’d see in Strange [a French superhero reprint mag] and other comics. More recently, I’ve been attracted by the strips of Charles Burns or Daniel Clowes (…) I like this vision of the city, cleaving to reality while leaving the door open to the supernatural. These authors create a sideways banality (“un banal decalé”).

The city, anyway, is never so beautiful as when it is the medium of a story.

We architects are not supposed to tell stories.

And at the same time, our role is to imagine places for living. This debate about the ‘scripting’ of life in the architect’s work is extremely interesting.”

So it would seem that comics provide a source of inspiration, but also of reflection.

As Trottin indicates, narrative is inherent to architecture yet secretive, difficult to articulate; one can, however, follow possible architectural narratives in comics. Comics can serve as a sort of test lab for the liveability of a space. It is always a challenge, in an architectural drawing, to show how human beings will occupy and inhabit a space.

But if there’s one thing comics characters do well with architecture, it’s to inhabit it– and architects are very much aware of this.

Reza Azard, from the Projectiles studio that designed the Archi & BD exhibition:

“For architects, drawing is primordial, it even represents a great part of our work. Before construction, there’s the project that must be drawn and, in order to convince, the drawing must express life, emotions, things one finds in films and in comics, which are media that place man in his context. Many architects are inspired by films and comics.”

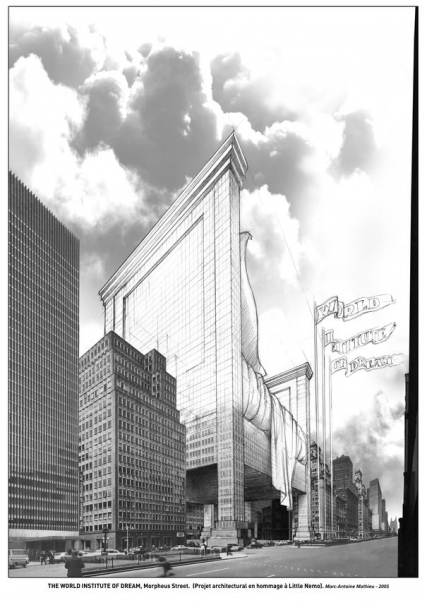

As a parodic, playful witness to this inspiration, this tribute to Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo by cartoonist Marc-Antoine Mathieu:

(Comics certainly are also useful for presenting the architects’ work: Trottin’s Peripheriques agency produced its 2003 catalogue in the form of a comic book. The same goes for the Danish agency BIG, which has sponsored a travelling exhibit of its work– ‘Yes is More’, a parody of Mies Van der Rohe’s dictum ‘Less is More’ — jointly with a comics-formatted catalogue; see the result here)

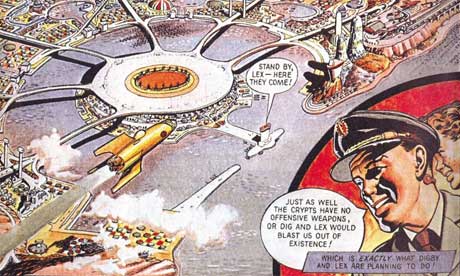

And architects also revel in the sheer invention and vitality of comics. Here’s the cover of a manifesto by the 1960s British architectural agency Archigram:

Yes, this draws on the Pop Art and Camp vibe of the times, but I prefer to think the Archigram crew was attracted by the brashness, the childishness, the sense of play of comics — of illicit creativity.

They certainly proposed fantastical projects that could, indeed, have come straight from the comics, such as their Walking City:

Norman Foster has done more than any other architect to bring to life some of the spirit, and even the fabric, of the optimistic, technologically underpinned world celebrated in the futuristic British strip Dan Dare by cartoonist Frank Hampson.

Foster is in no doubt that Dan Dare has been a genuine influence on his work. In 1983, he even commissioned John Batchelor, a former Eagle artist, to draw the new Renault Distribution Centre in Swindon as a pullout poster for the Architectural Review, which ran a feature on Foster’s approach under the headline: The Eagle has landed. (The Eagle was the comic magazine in which the strip ran.)

“I loved the coloured, cross-sectional, technical drawings that appeared in the middle of the Eagle after Dan Dare,” says Foster.

One Dan Dare episode features Big Ben housed in a Perspex sheath, shaped exactly like Foster’s famous Swiss Re building in the City of London, the so-called ‘gherkin’ (pictured above).

Laurie Chetwood, born in 1957, is one of Britain’s leading architects. His most recent proposal is a $300m space-age sanctuary for world leaders in the Nevada desert. It looks exactly like something Dan Dare would manoeuvre his rocket around. Says Chetwood:

Architects don’t often seem to have had childhoods. Or at least, they pretend they can’t remember them, in case they appear to be less than earnest. My cousins handed me down their Eagle annuals, and I became a Dan Dare fan. I drew loads of space rockets and strange machines.

The draftsmanship skills required of a cartoonist and those required of an architect are similar– rigor, clarity, mastery of perspective and space, a controlled line, a good sense of measure and proportion.

(These skills, however, may seem less and less relevant to young architects in this age of computer-aided design; I once had a book entitled Perspective for Architects — incidentally the most useful book on drawing I have ever owned– in which the author scolds architects for their poor draftsmanship, comparing them unfavorably with illustrators and cartoonists.)

Many cartoonists have had training in architectural or technical drawing. Dave Gibbons, of Watchman fame, trained as an engineer ( he points out that not only could he draw a window, he could also build one), as did Jacques Martin, the author of the Alix series set in ancient Rome:

Jacques Martin, Alix

The late Marshall Rogers trained as an architectural draftsman, a fact readily apparent from his city backgrounds:

Marshall Rogers and Terry Austin, Detective Comics

Some cartoonists, however, go beyond depictions of buildings and get involved in building design and decoration.

The most basic way is the painting of exterior murals. And, indeed, the city of Brussels — one of the historic capitals of comics creativity — has commissioned 32 of them to adorn its streets with the works of popular cartoonists:

Le Chat, by Phil Geluck

Cory Moussaillon, by Bob De Moor

However charming these be, for the most part the murals don’t integrate well with the buildings — merely adding an illustrative layer on the facades– sometimes to add a gag:

Gaston Lagaffe, by Franquin

Here is a complete series of photos of this delightful urban phenomenon

But one in the series does seem to dialogue with its support:

… and this doesn’t come as a surprise, for the comics artist who designed it has thought much about architecture over his three-decade- plus career’s span: François Schuiten.

A typical architectural fantasia by Schuiten

And another one

His most renowned series in that vein is Les Cités Obscures, written by Benoit Peeters.

Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters

These stand-alone but thematically connected works deal in an often fantastic or metaphoric mode with humanity’s relationship with the city and with buildings.

In Les murailles de Samaris (the Great Walls of Samaris) a mysterious city seems to be in a perpetual state of flux, with shifting walls and morphing buildings:

From Les Murailles de Samaris

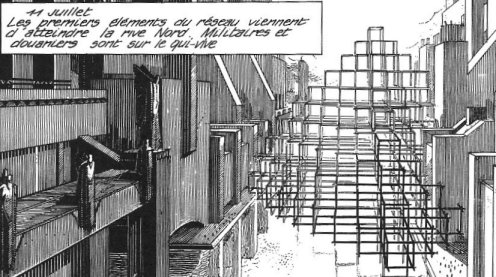

In La Fièvre d’Urbicande (Fever in Urbicand) two cities that have always been separate are joined by a strange grid that starts out as a desktop toy and grows slowly to immense size, overlaying the cities:

La Tour (The Tower) is Schuiten’s take on the Tower of Babel legend, with a nod to Borgès, featuring a Medieval-style tower of seemingly infinite height and depth.

All in all, there are nine Cités Obscures albums so far; several are available in English from NBM.

And another urban landscape…these are addictive

It comes as no surprise that an artist of his accomplishments should be solicited to realise those architectural “dressings” known as scenographies. And, indeed, Schuiten has done several; most spectacularly, a platform on the Paris Metro’s ‘Arts et Métiers’ subway station:

You step into a dream of “steampunk”, a Jules Verne setting made real, a way station in the Cités Obscures.

In walls of copper sheathing, portholes worthy of Captain Nemo’s Nautilus display models of marvellous inventions from the Arts et Métiers museum.

In the tunnel’s ceiling, we see the ominous edges of gigantic gearwheels…for what obscure purpose?

Schuiten has also designed scenographies for the Pavilion of the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg at the Seville World’s fair, and the Pavillon des Utopies (A Planet of Visions) at the Hanover World’s Fair.

World’s Fairs? How appropriate for a designer of architectural utopias.

Schuiten comments:

“The risk in drawing utopia, is that it isn’t incarnate, it distances itself from reality, that it is complacent in its own invention and detaches itself from the roughness of reality. So, when one works on worlds, one wishes to test them> my drift into scenography allowed me this, and in exchange has modified my draftsman’s gaze. This back-and-forth between the two forms of expression creates a new awareness of what drawing can bring and what reality cannot.”

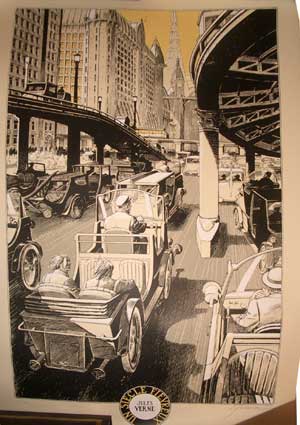

What the heck, I can’t resist… Schuiten adapts Jules Verne’s ‘Paris au XXeme Siecle’

François’ brother and erstwhile collaborator, Luc Schuiten, has abandoned comics altogether and become an architect full-time.

His projects, though, show definite comics influences in their utopian designs:

Jean-Claude Mézières, the artist on the noted science-fiction series Valérian, was commissioned by the city of Lille, France — the European Capital of Culture for 2004 — to transform a boulevard into a spaceport landing strip: ‘ Le Chemin des Etoiles’ (The Way of the Stars):

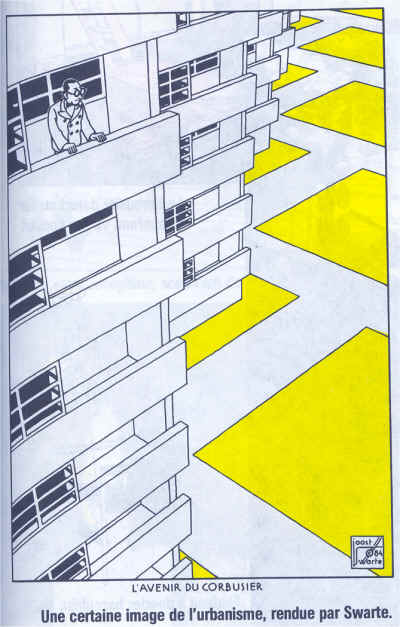

The Dutch illustrator and cartoonist Joost Swarte is also known for the strong architectural presence in his drawings; he is yet another artist with training in industrial design:

Joost Swarte

Swarte has collaborated with architects to actually design and realise buildings.

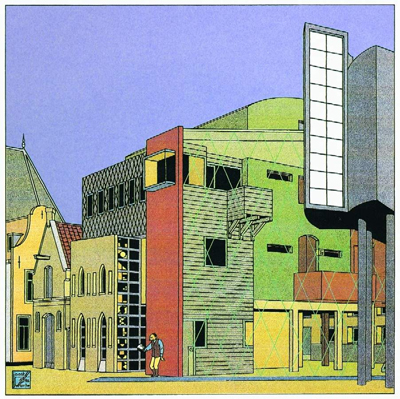

His first major project was the Toneelschuur Theater in Haarlem, in partnership with the Mecanoo agency:

Swarte:

“Architecture projects are big puzzles to be solved… An architect friend pointed out that a wall is a pen-line on paper, while it has thickness in the real world. I’d forgotten that when I had started organising the different spaces in the theater. But walls make up about 15% of a building’s area! Comics also have this advantage over architecture that you can launch a project with zero budget…”

The Swarte/Mecanoo design for the Toneelschuur Theater in Haarlem

The director of the Hergé foundation, Nick Rodwell, then asked Swarte to design the Herge Museum in Louvain-la Neuve; with Thierry Groensteen — a man possessing great experience as a comics curator — and Philippe Godin, the foremost Herge scholar, as consultants, he came up with a design for the building that was completed by architect Christian de Portzamparc.

The Musée Hergé under construction

Front approach to the museum

The main hall

Footbridges link the four main exhibit rooms; Pontzamparc compares them to the gutters between panels

Note how the spaces reserve surprises and summon the spirit of exploration and adventure of a Tintin album:

Side view; note the colors, all carefully matched to those in the Tintin albums.

Swarte:

“It’s bizarre, but when I’m working on an architecture project, I think about the comic I could make of it. And on the other hand, when I’m doing a drawing, I start drawing facades, and imagine what I can put behind them. I can’t fight it! It’s natural.”

The Musée at dusk

Christian de Portzamparc:

“The Musee Hergé is perhaps the only example of a comic transformed into architecture. At least, it has materialised in three dimensions”.

Joost Swarte also designs for other media. Here he presents his tapestries at the Stadhuis (City Hall) of Haarlem

Hob-nobbing with architects is all very well, but why shouldn’t the guys who actually build the building inspire cartoonists? Why this snobbery towards the hard-hats? Cartoons may lead to construction, but can’t construction — with your own two hands — lead to cartoons?

The cartoonist Alan Weiss spent a summer on a construction site; it got him thinking about the lack of real proletarian heroes in mainstream American comics.

Thus was born Steelgrip Starkey, a genuine blue-collar fusion of Li’l Abner, Edison, and Doc Savage: a superhero who disdains violence for the kicks of building huge wicked cool projects the world over! Check out this quirky but good-natured series from Marvel Epic.

Yes, I know — the full title sounds like a porno movie. So sue me already.

***********************************************************************************

There is a final, compromised but creative way for cartoonists to “realise” their architectural ambitions, through a third artform: the cinema.

Directors and designers have not been slow to call on the creativity of comics artists. Ron Cobb designed the ship Nostromo’s interiors for Ridley Scott’s Alien; Mike Ploog designed for films such as Tomb Raider.

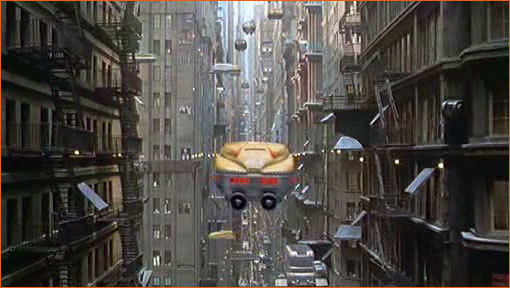

Two of France’s top science-fiction comics artists were the chief designers of director Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element, and that film’s futuristic New York: Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud and Jean-Claude Mezieres. Here are a few of Mezieres’ preliminary sketches:

And here’s Meziere’s designs come to life:

Mèzière’s city comes to cinematic life in this clip.

Enki Bilal has gone further, directing as well as designing Immortel (Ad Vitam), an adaptation of his Nicopol series of albums:

Another option for cartoonists who wish to concretise — if only virtually — their designs is video games. Such was the path chosen by Benoit Sokal, the creator of the anthropomorphic noir series Inspecteur Canardo.

Inspecteur Canardo, the police duck, in an introspective moment

Sokal was the designer behind the games Amerzone and Syberia.

This concludes my essay on comics and architecture; as a valediction, this advice:

Architects, draw more; cartoonists, build more.

****************************************************************************

“Concludes”? I wish! this is too vast a subject.

Where, for example, have I mentioned Alan Moore’s and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell, in which architecture is used narratively in such an innovative way?

What of the Japanese comics masters?

In other words, I can’t exhaust this subject, and follow-up columns on it will appear from time to time; as ever, your suggestions are welcome.

********************************************************************************

This is part 3 of a 3-part series. Click here for part 2 and part 1

What are the links between comics and architecture?

At first thought, not many, other than the banal facts that cartoonists draw a lot of buildings, and that a few modern buildings look like something whacky or sci-fi-like that could’ve come from a comic book.

I believe there are deeper connections.

A strip cartoonist ‘builds’ a complex structure, manipulating space to organise time and impose a narrative.

An architect does much the same thing.

Consider a museum, a cathedral, an airport terminal: there is an implicit narrative in each, with the visitor “reading” the constructed space.

These resemblances even show up in technical vocabulary.

We speak of the “construction” of a script; both a building’s floor plan and the roughs for a comics story show a “layout“.

(Speaking of floor plans, cartoonist John Romita Sr revealed that the first thing he did before blocking out a scene was to draw a floor plan, prelude to his mise-en-scène of characters; doesn’t an architect do the same with regard to a building’s users?).

The Pritzker prize-winning architect Christian de Potzamparc (who collaborated with the cartoonist Joost Swarte on the Hergé museum) said:

“When I made the lodgings of the rue des Hautes-Formes in Paris, in the ’70s, I created a dozen successive perspectives. Like a film. […] It happens that this subjective vision is also the perception of the cinema but above all of comics.”

Rue des Hautes formes: lodgings designed by Portzamparc

Let’s now hear the thoughts of François Schuiten, a cartoonist who over his career has gained renown for his architecture- centred tales:

” [Between architecture and comics] there are identifiable meeting points. For example, one of the primordial things in comics is to bring the eye into the picture, and for this, architecture is a good tool, for it allows one to guide, to orient the gaze through the play of materials and light. What equally interests me is composition. The comics page — it resembles a topography, it plays on the relation between positive and negative space.

One can therefore compare the writing and composition of a page with an architect’s preoccupations.”

Lithograph by Francois Schuiten

“There are,” Schuiten goes on, ” in my stories, practically no drawings without a human character. I don’t get so much pleasure from drawing buildings for themselves. I like them to the extent that they can help me set a scale, tell a story, nurture fields of tension.”

Another Francois Schuiten cityscape

Schuiten often characterizes the city and comics as comparable systems:

“That’s what interests me. Benoit Peeters [Schuiten’s longtime scripter] and I track that: the character caught in a system. How an environment builds us, reveals us or destroys us. What organic links the city weaves to us. Those fractal links that arise between very small and very large things. Comics and architecture are good tools for discussing that. […] Small things must reflect the dimension of the system, detail becomes synecdoche, a carrier of meaning.

For me, there too, it’s possible to establish a link, if one wishes, between architecture and comics. Comics are the art of the sign, and through the staging of a building’s details, a lot can be expressed.”

(quoted from an interview with Stephane Beaujean; tr. from the French by A.B.)

Cover by Schuiten

Schuiten is articulate about architecture and comics for good reason; that has been his theme for over three decades. We shall return in detail to him in a later installment.

Architecture and architects are not that uncommon a theme in comics.

1983 saw the debut of Dean Motter’s comic book Mr X: the eponymous hero being the architect of a utopian metropolis, Radiant City, gone wrong; besides Motter, notable artists to draw it include Jaime Hernandez, Paul Rivoche, and Seth.

Mr X by Paul Rivoche

This dystopian approach didn’t prevent the artists from reveling in retro-futurist stylings; indeed, that seems to have been largely the raison d’être of the comic, whose real hero was the city itself.

Mr X art by Jaime Hernandez

In Hermann Huppen‘s Babette, we follow in great detail the building of a medieval cathedral:

click to enlarge

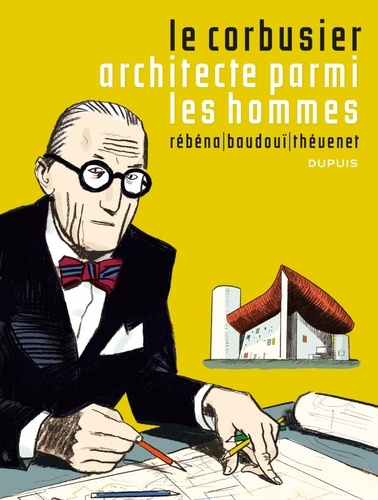

Jean-Marc Thévenet (script) and Frederic Rebena (art) have crafted a comics biography of Le Corbusier, the great Swiss architect:

The album delves seriously into the process of creating architecture, and avoids hagiography:

Andreas appropriates the buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright for his 1995 Le Triangle Rouge, a strangely oneiric multi-layered tale not unlike this year’s film Inception; Wright’s buildings seem the only sure anchor for the reader’s understanding.

The architect as savior from chaos?

2009 saw David Mazzuchelli‘s Asterios Polyp, the story of a “paper architect”– one who never actually builds anything– who has lost his way in art as in life:

(Asterios Polyp was extensively discussed in a roundtable on this blog)

But for a devastating critique of architecture, of urbanism, and indeed of modern civilisation– nothing surpasses Robert Crumb‘s brief, wordless, building-haunted masterpiece, A Short History of America:

I find most admirable in Crumb, here and elsewhere, his unflinching observation of the ugly, the banal, the quotidian of the city that we erase unconsciously from our perception.

There is a telling scene in Terry Zwigoff’s documentary film Crumb where the artist shows an album of photos he’d commissioned, showing freeway intersections, clusters of lampposts, concrete islands… all the most boring and brutalist “invisible” patches of our urban environment. Crumb pointed out that there was no reference accessible for these despised spaces, so he had to have them documented himself.

This is a true artist: one who sees what we don’t want to see, and opens our eyes to it.

Sofia, Bulgaria, 1966, by R.Crumb

Crumb was far from the only artist from the ’60s–’70s underground comics movement to show an interest in architecture. Bill Griffith, in his Griffith Observatory and Zippy strips evinced a fascination with the bizarre and often garish building vernacular that characterises so much of America’s urban landscape — showing affection for the trashy and banal:

Griffith organised a campaign to have the ‘doggie head” sign that so inspires Zippy be landmarked…and lo! It was. Click image to enlarge.

Architecture, then, can be the subject of a strip or cartoon…but obviously,the great majority of comics do not deal directly with architecture.

How, then, do comics and architecture interface? How do comics use architecture?

The prime use is functional. Architecture and landscape are the setting wherein the cartoonist will stage the actions of his characters.

Many cartoonists will keep the architectural features spare, to the point of minimalism; this stems from a valid aesthetic that heightens the narrative in contrast to its context. ( Others will do so out of laziness or hackery).

Look at the buildings in these panels from Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy:

They are reduced to their barest essence: just enough to convey the idea of “building”.

Consider the economy shown in this depiction of a shopping mall in Archie:

Click to enlarge

Just enough graphic information conveyed, and no more, to advance the story.

This aesthetic became a house style at Fawcett Comics’ Captain Marvel in the ’40s, as defined by C.C. Beck and encoded by the Jack Binder sweatshop; this page was drawn by Kurt Schaffenberger:

click to enlarge

In Europe, too, this stripped-down approach had many adherents. The ‘ligne claire’ (‘clear line) school of Belgium is famous for the detailed backgrounds of Hergé, E.P.Jacobs, or Jacques Martin; but it also featured more humdrum strips such as Chick Bill, by Gilbert “Tibet” Gascard that kept the architecture fairly spare and functional, though accurate:

click to enlarge

Beyond the purely functional, architecture in comics is illustrative. It complements and augments the story; it creates an ambience; it reinforces a fiction’s believability.

This is key for comics of historical fiction.

Renaissance Paris; from ‘Les sept Vies de l’Epervier‘, drawn by Juillard.

Prince Valiant, by Hal Foster. .

The above strip is a curious case; it combines scrupulous accuracy in depiction with heedless anachronism in setting. For example, the above drawing shows a typical 12th century castle and contemporary knight; but the action is supposed to take place in the 4th century!

Architecture is a capital component of science-fiction and fantasy comics, essential for establishing credibility.

Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud: The Long Tomorrow

The veteran fantasy artist Mike Kaluta notes that the believability of drawn architecture depends on the artist being able to visualise the invisible parts of a building– its hallways, pipes, rooms– even if none of them are shown the reader.

Carson of Venus; art by Mike Kaluta

Sometimes past and future collide, as in Gene Ha’s richly imagined The Forty-Niners:

…where early 20th century architecture is augmented by futuristic buildings; a design approach reminiscent of that of Syd Mead on the seminal science-fiction film Blade Runner.

But Mead was anticipated in this by Enki Bilal, who perfected the “mash-up” of futuristic, contemporary, and past architecture:

Besides the historical past or the fantasised future, of course, architecture establishes the verisimilitude of the present. Certain cartoonists have so excelled at this that they have become indelibly associated with a particular city.

Jacques Tardi is the cartoonist laureate of Paris:

Jacques Tardi, ‘Nestor Burma’: Paris in the 1940’s

Jacques Tardi, ‘La Position du Tireur Couché’: Paris in the 1970’s

London arguably belongs to Carl Giles:

For New York, my choice would be Will Eisner.

I was born in New York and lived there for the first 14 years of my life. I can attest that Eisner’s rendition of the crusty, crumbly, fire escape-festooned tenements and elegant stooped brownstone townhouses of the Big Apple are the real deal.

New York view, by Will Eisner

Eisner’s yenta mom substitute bawling out the Eisner stand-in (en Français in this translation). From ‘A Contract with God’.

The cartoonist Chris Brunner notes about the above image:

“Worth mentioning is the way architecture can be used as a graphic device to create panels within panels. A couple of the images here touch on this (…) the Eisner fire escape shot- the man part of the outdoor environment, the woman framed by the window in a way that suggests its own panel.”

Mark also how New Yorkers appropriate the fire escape as a mixed private/public space.

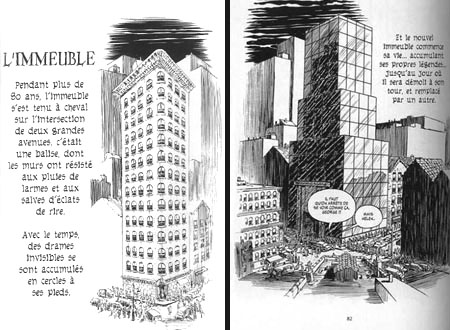

Eisner again, in French again.. a lucid look at the impermanence of New York edifices. From ‘The Building‘.

There is, of course, a quicker and lazier way to identify a city: landmarks, such as the Statue of Liberty:

The Gift, by Alfredo Alcala

…or the Empire State Building:

(This use of famed monuments has been thoroughly sent up by Scott McCloud in his Destroy!, where two rampaging superheroes demolish every famous landmark in New York:)

I call this use of architecture in narrative emblematic.

These landmarks can fulfil a metonymic function:

From Doonesbury, by Gary Trudeau.

The manor of Moulinsart (Tintin) by Hergé. Click image to enlarge.

The Batcave (Batman).

Snoopy’s Doghouse, from Peanuts (art by Carl Shulz)

The bard’s house (Astérix) by Uderzo

The Baxter Building (Fantastic Four) by Jack Kirby

(Compare with the Batcave: a staple of the ’60s superhero comic, the cutaway view of the hero/villain’s headquarters is but a memory now. You kids today…I just don’t know…)

The Money Bin (Uncle Scrooge) by Carl Barks

Pop’s Chocolate Shoppe (Archie).

The above location also functions as what T.V. sitcom writers call a “crossover set” — a place where any of the characters can meet, and any plotlines intersect.

The Marsupilami’s nest (Spirou), by André Franquin

Superman’s Fortress of Solitude; art by Ross Andru and Dick Giordano

These recurring landmarks serve as touchstones for the regular reader, offering the reassurance of familiarity; much for the same reason that Donald Duck always wears a sailor suit, or that Superman wears tights, a cape, and his underpants on the outside.

Sometimes architecture is used to signal a genre.

Arcane’s castle (Swamp Thing) by Berni Wrightson

Big spooky castle = horror comic

Nick Fury, agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. by Jim Steranko

Gratuitously futuristic décor = cool spy thriller.

The next function of architecture in comics I call expressive. The cartoonist uses architecture and landscape to evoke specific emotions in the reader.

See the expressionistically twisted yet realistic world of Alack Sinner, by Muñoz and Sampayo:

The harsh streetscape mirrors the sense of doom and injustice that pervades this noir series.

Less baneful, but as subjectively gritty and urban: Will Eisner’sThe Spirit :

Even the buildings are bent to the story– to the very logo:

Or consider Jack Kirby’s stunning imaginary cityscapes, such as Asgard:

click image to enlarge

…or his Great Refuge:

…or his New Genesis:

Now, note that many, if not most, of the buildings in the above Kirby panels have no discernable function. Or, rather, their function is emotional– to instill awe.

It’s far different emotions that are invoked by the quotidian landscapes of Jiro Taniguchi: peace, melancholy, mixed with a quiet joy.

The last use of architecture in comics celebrates the quiddity of the artist’s vision; for want of a better term, I call this use poetic.

How else to describe the quirky lunacy of George Herriman‘s ever-shifting buildings:

click image to enlarge…or the baroque hallucinations that Jim Woodring conjures up for dwellings?

Five categories, quite subjectively and idiosyncratically arrived at: functional, illustrative, emblematic, emotive,poetic. Of course, most comics architecture features more than one of these aspects, often all of them.

And this is nowhere truer than in Trondheim and Sfar’s Le Donjon series, where the titular dungeon, a seemingly infinite Gormenghastian source of terror and desire, dominates the actions of every inhabitant of its world.

It’s also obvious, merely from all the examples shown above, that architecture in comics can’t be considered in isolation: it relates to design, to landscape, to scenography, to narrative.

In this installment, we surveyed what architecture brings to comics.

But do comics have anything to bring to architecture?

We’ll examine that puzzle in part 3.

—————————————————————————————

This is part 2 of a three-part series. Click here for part 1 and part 3.

Here’s a link to a great recent post on notable comics places.

If you wish to see the work of one of last century’s true masters, this site collects a stunningly huge, searchable database of Giles cartoons. The “random cartoon” function is addictive!

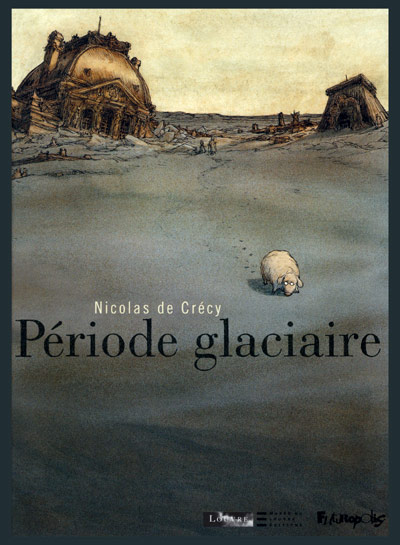

Art by Nicolas de Crecy

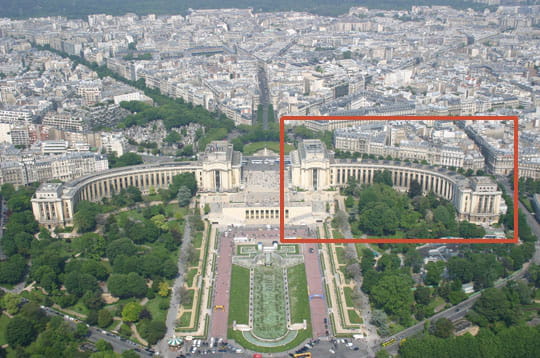

Until January 2 2011, the official French museum of architecture — La Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine — is hosting an exhibition on comics and architecture, Archi et BD: La Ville Dessinée in the Palais de Chaillot, Paris.

The museum, in the red square, as seen from the Eiffel Tower

The exhibition, curated by comics scholar Jean-Marc Thévenet and architect Francis Rambert, showcases over 360 items in a witty scenography by the Projectiles agency that evokes the nature of a comic strip– the visitor being its hero. The works are hung on rippling walls of translucid, backlit PVC.

I found this not altogether satisfactory, as the backlighting of original art tended to render it also translucent, hindering its readability.

The exhibition kicks off with Il était une fois Winsor McCay (Once upon a time, there was Winsor McCay). McCay (1869 – 1934) and his marvelous work, from the turn of the last century, is a fitting chronological start; few cartoonists indeed have matched his astounding architectural inventiveness:

Winsor McCay et ses héritiers (Winsor McCay and his heirs) highlights the work of such contemporaries of McCay as George McManus and Frederick Opper, all pioneers of the comic strip– which had very strong urban overtones from the start. No wonder: the explosive growth of the great American cities coincided with the appearance of the comic strip in a mass circulation urban press.

New York, première icone (New York, the first icon) is the next subsection, and the array of depictions of the Jewel of the Hudson is dazzling.

Broadway’s lights, from the strip ‘Mary Perkins: On Stage’, by Leonard Starr

New York street scene by R.Crumb

Aside from the American cartoonists, it was a surprise to see how much New York had inspired European ones.

Art by Janry. Note the racism of the caricatures– the interior is even worse!

Les Superhéros des mégapoles américaines (The superheroes of the American megalopolises) continues the theme, with art by Jack Kirby, Gene Colan and Will Eisner, among others.

The notes point out to the European visitor how varied and dramatic the p.o.v. shots are in superhero comics, the better to inject melodrama into the story — something, as an American, I was so used to that it took a European to underline how unusual this was in the broader context of world comics.

This sub-section is marred by the looped projection of a 1940s Fleischer Superman cartoon; its theme music blares continually down the gallery.

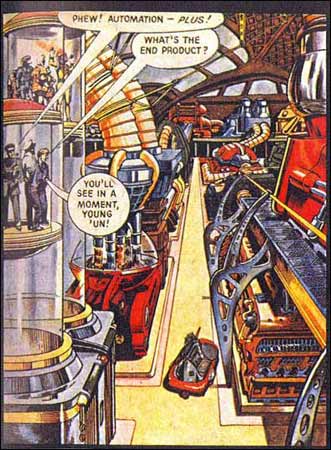

The next major section, L’esprit moderne (The modern spirit), starts out with l’Exposition Universelle de 1958 et l’Ecole belge (The 1958 World’s Fair and the Belgian School). The aforesaid World’s Fair took place in Brussels, and coincided with a post-war generation of young Belgian cartoonists such as André Franquin and Will: both showcased the new, futuristic modernism, as expressed in gadgets, vehicles– and buildings.

From ‘Tif et Tondu’, by Will

This style has since come to be called the ‘style Atome’, lovingly re-created by younger cartoonists such as the late Yves Chaland:

La Ligne Claire (The Clear Line) showcases major exponents of the eponymous school of comics drawing, with examples from heavyweights like Hergé (Tintin), but also such modern practitioners as Ted Benoit and Theo Van den Boogaard; it’s a style that, as architect Christian de Pontzamparc points out, is ideal for depicting buildings– and is partly inspired by architect and engineers’ concept drawings:

I confess that my affection for the ‘ligne claire’ comics is tempered by a distaste for their excessive cleanliness– like a Swiss housewife’s–, their blueprint-like precision, in a word their coldness: frigidity is one of the most insidious and damning sins of art. After the neat streets of Hergé one may long for the scuzzy Harlem of R.Crumb‘s sketches. This coldness, of course, is entirely appropriate for the sardonic irony of a Swarte, or the retro stylings of a Benoit.

Pontzamparc joined the most celebrated contemporary practitioner of the Clear Line style, the Dutch cartoonist and illustrator Joost Swarte, to design the Hergé Museum (which is represented at the exhibition by a model).

The third section is Itinerances de la bande dessinee (Wanderings of the comic strip). This heading is a bit of a catchall, covering the notion of travel both literally (as in Joe Sacco‘s trips to Palestine, or Loustal‘s Carnets de Voyage) and figuratively (Chris Ware‘s psychological explorations).

Village from Loustal’s `Carnets de Voyage`

Here, too, is a genuine weak spot of the exhibition– the relative paucity of strips from Japan, despite the claim that Tokyo is the new capital of comics.

Jiro Taniguchi‘s lovely Walker is presented, though:

I was charmed to discover examples of modern Chinese comics, such as those of Zou Jian-Le chronicling the transformation of Beijing:

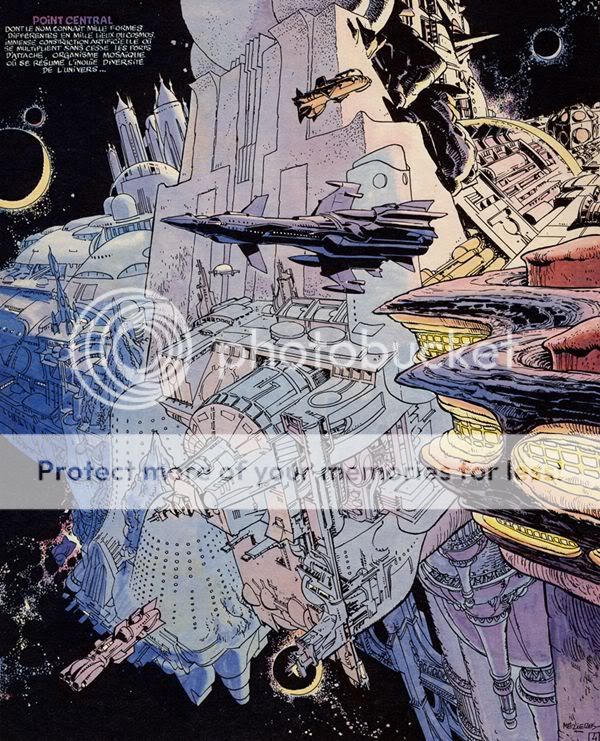

This is also the section for Utopies (Utopias), the wild urban landscapes of fantasy and science fiction, such as those of Jack Kirby or of Jean-Claude Mézières:

New York in the 23d century, by Mézières

Another Mézières city view

A stunning space city by Mézières…if I show so much of this artist, it`s probably because he was once my cartooning teacher!

A futuristic city by Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud

This is also the domain of the future catastrophe, allowing strange visual depictions of current cityscapes, as in Nicolas de Crecy’s Période Glaciaire:

or in Jack Kirby‘s Kamandi:

Or consider the nightmare urban fantasias of Schuiten, as in his La Fièvre d’Urbicande:

Here, too, are exhibited some of the more “sci-fi-ish” projects of architects; always fascinating to see, though I am unconvinced of any links to comics:

Deepwater undersea lab by Rougerie, 1974

The final section, Regards Croisés (Crossed Viewpoints), is basically a mishmash of installations of various sorts and the nowadays-obligatory bank of computers for a set of boring interactive exercises.

Overall, a stunning experience. Here is surfeit for lovers of comics as well as of architecture; and matter for thought on the interaction of the two artforms, which we’ll explore in part 2.

—————————————————————————————————————

This is part 1 of a 3-part series. Click here for part 2 and part 3

Until January 2 2011, at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine (1 place du Trocadero, Paris). Tickets: 8 euros — a steal. The museum is also well worth visiting for its stunning permanent collections, particularly its many architectural models.

PDF of the press release (French and English)

The museum’s website

On Wisconsin Public Radio’s Here on Earth program — moderated by the able Jean Feraca — Gene Kannenberg and I chat about Tintin and field listeners’ calls; you can find a streaming of the show at this link.

Enjoy my dulcet tones– or, rather, my robotic stammer.

———————————————

Some have chided me for overlooking the most excluded of “others” in the Tintin oeuvre, i.e. women.

This is indeed true. In all the albums, there are only three or four women with so much as speaking roles. I interpret this as a hangover from the fiercely puritanical Catholicism of Hergé‘s youth, mixed with his own dose of misogyny. Hergé’s own explanation fails to convince:

“True, there are only a few women, but not out of misogyny. No, it’s simply because as far as I’m concerned, women don’t belong in a world such as Tintin’s; it’s one dominated by male friendship, and there is nothing ambiguous about such friendship! Of course there are only a few women in my stories and when they do appear, they are caricatures, such as Castafiore.

If I were to create a character who was a pretty girl, what would she do in a world where all the other characters are caricatures? I love women too much to turn them into caricatures!

Anyway, pretty or not, young or not, women are rarely comical elements.

Would it be the maternal side of women which prevents us from making fun of them?”

(That last sentence would be of interest to a psychiatrist…and, indeed, Hergé spent years in analysis.)

But there is one woman in Tintin with enough force and character to dominate any story she shows up in; yes, the divine ‘Nightingale of Milan’, the Empress of the Opera:

Bianca Castafiore!

What mere male can fail to wilt before such beauty and power?

As the good Captain Haddock says, a formidable woman.

Ah, Captain, submit to the inevitable; the charm and might of La Castafiore will keep you in her thrall!

The transition from ogress to goddess is most satisfying, and is consummated in Hergé’s wittiest Tintin album, Les Bijoux de la Castafiore (‘The Castafiore Emeralds’)

Love her though I do, I must concede that the Castafiore is a monstrous caricature of woman.

What I delight in, however, is the way she serenely floats above every catastrophe…even when on trial for her life (in “Tintin et les Picaros”) she turns the courtroom into an opera stage!

You go, girl!

————————————–

Tintin wasn’t Hergé’s only series.

One may applaud the cosmopolitanism of the later Tintin albums (and of the redacted earlier work), yet still regret a certain earthy malice inherent to the initial work: Tintin was, in the beginning, a brawling, cunning trickster more than a boy scout. He was also definitely Belgian, as contrasted with the somewhat bland “international” Tintin of later years.

As a counterpoint, I recommend (to you who speak French) the series of albums featuring Quick & Flupke, a pair of wicked little Brussels street urchins.

The Belgian equivalents of the Katzenjammer kids or of Max and Moritz, these two lively pests were well grounded in the rich culture of that teeming capital, Brussels.

The series, composed of two-page stand-alone gags, also lets Hergé indulge one of his major talents as an entertainer– the gagman… but in a childlike, gentle mode that didn’t exclude mild satire:

And the establishment– represented by the police– comes in for some tweaking at the hands of this delinquent duo:

Try this strip some time!