It took me a very long time to realize that mainstream comic book industry isn’t at all interested in me, isn’t at all talking to me; that it is, in fact, talking over my shoulder to the straight white man-boy (and people who identify with the straight white man-boy) reading his comic book behind me.

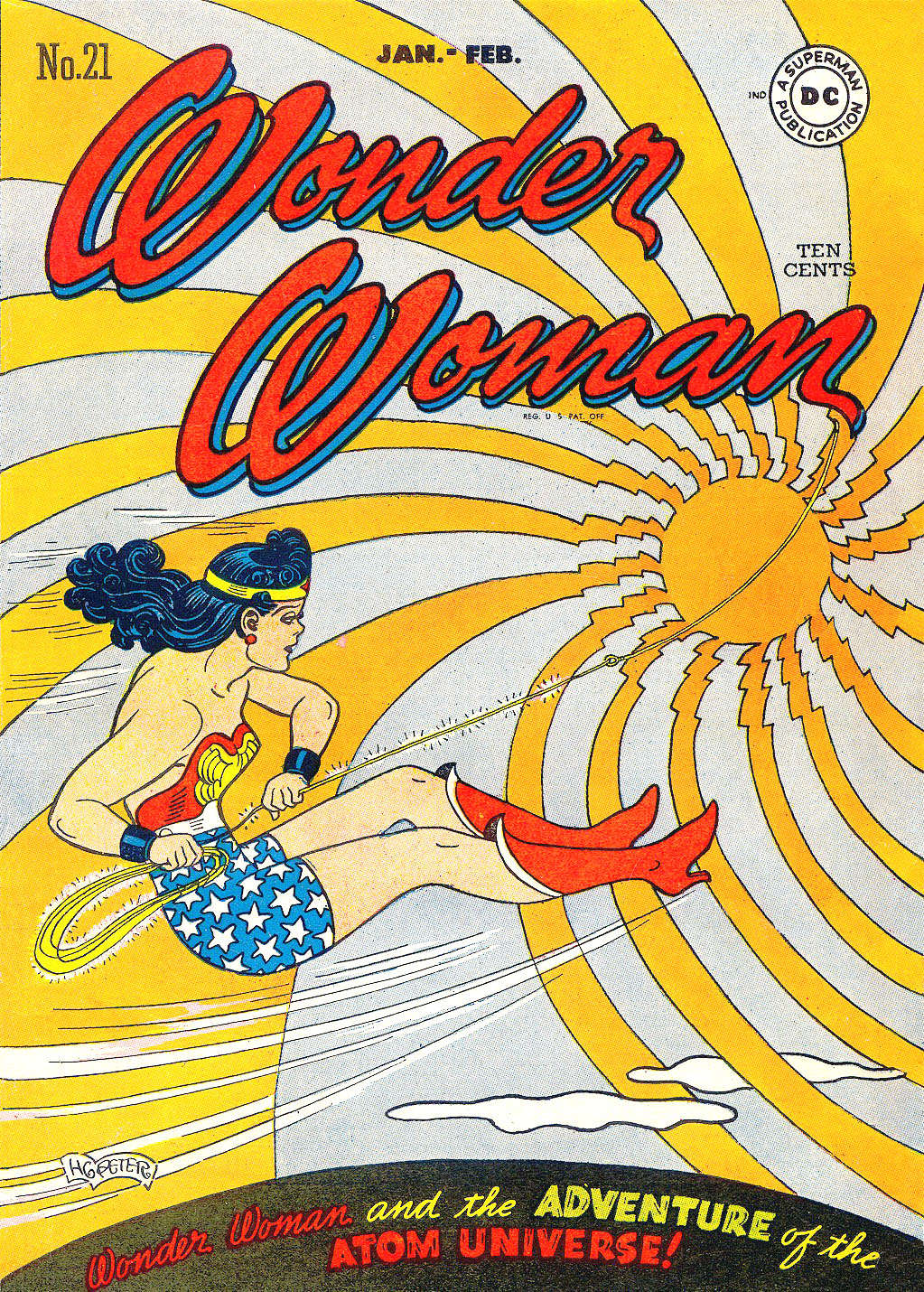

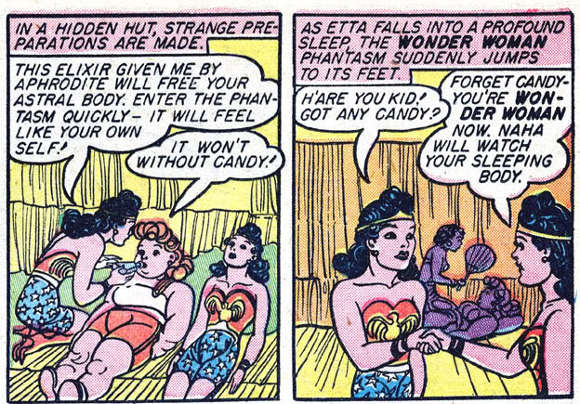

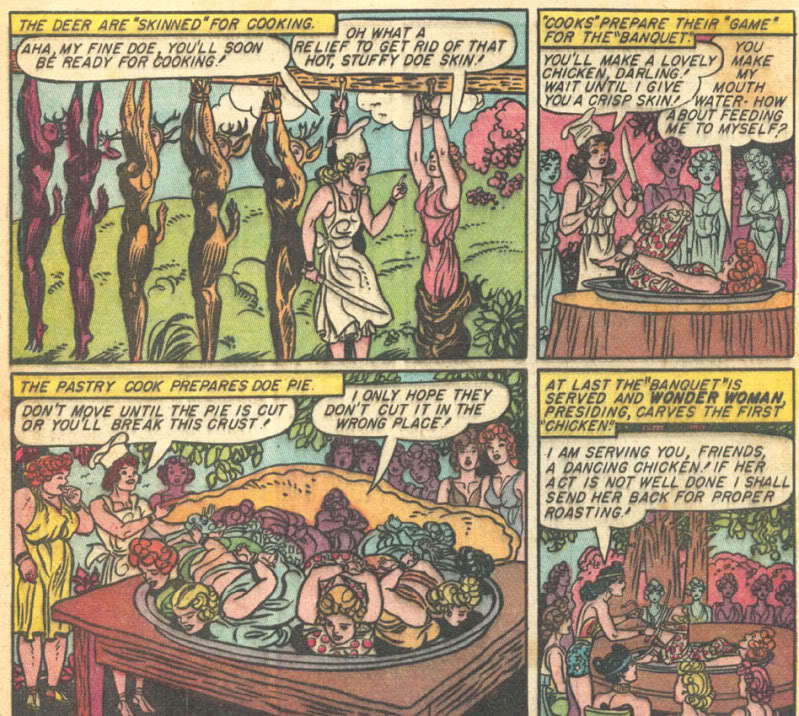

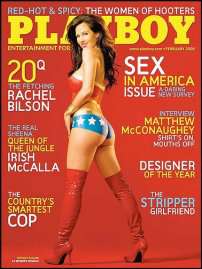

Every time I imagine that I’m just being hyperbolic, seeing problems where none exist, and return to the beloved hobby of my childhood, I am unceremoniously reminded of just how hostile that environment is to a conscious mind. I made the regrettable mistake of reading the current issue of a comic book that I had long abandoned: Wonder Woman. The book’s current course, and current success, can be traced, I believe, to its decidedly macho-friendly, anti-feminist tone.

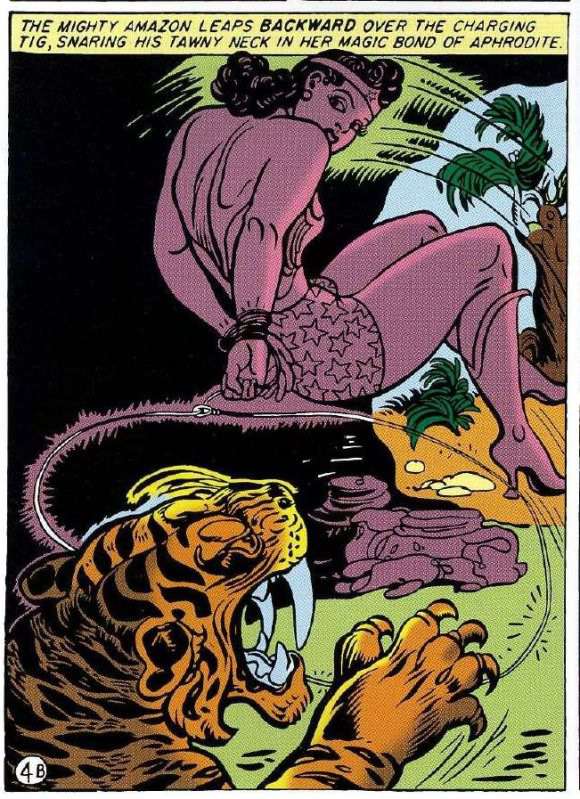

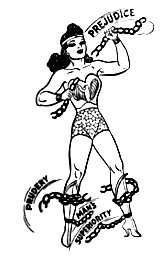

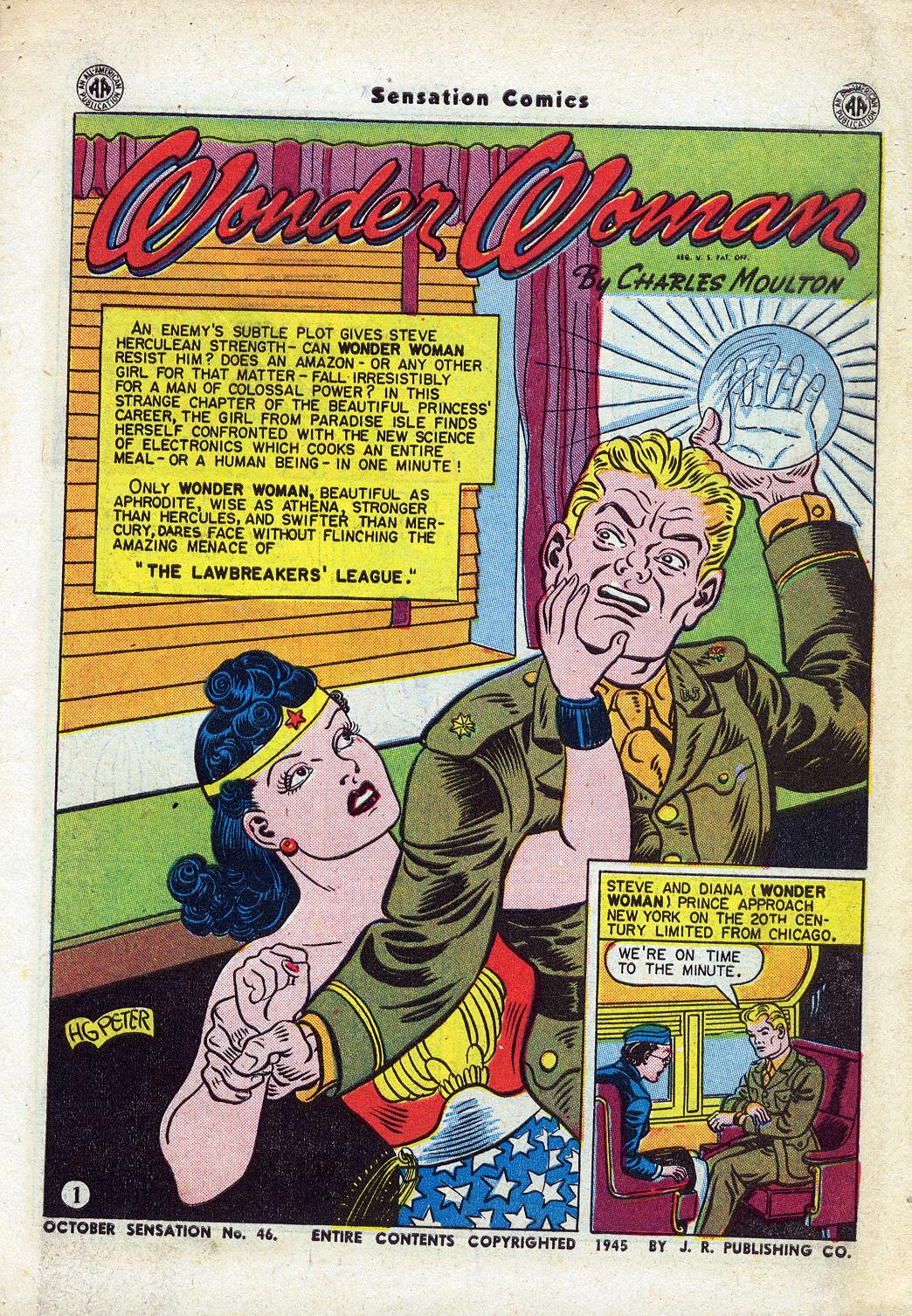

It wasn’t enough that this new iteration of the character jettisoned her previous origin of a child being formed from clay by a desperate Queen Hippolyta and blessed with powers by loving set goddesses (and one god) from the Greek pantheon. To add insult to injury, we were told that not only was Wonder Woman now the product of a tryst between Hippolyta and Zeus, the womanizing king of the Olympian gods, but that she also belongs to a tribe of man-hating women that periodically creep away from their island hideout to have sex with unsuspecting men, murder them, and would murder the male offspring from those unions too if not for the kindness of another god. If it sounds like ancient Greek misogynist propaganda with a modern twist, it’s because it is. And it is, in my opinion, all for the benefit of making Wonder Woman relatable to a bunch of men in the industry and in the audience, who simply can’t relate to a character designed to attack patriarchal notions and empower women in revolutionary ways.

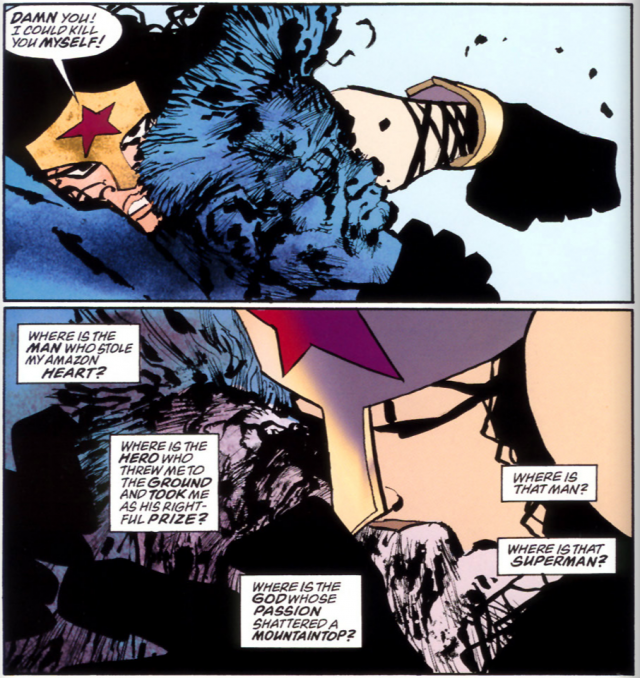

In the latest issue of Wonder Woman, another character, a new god named Orion, slaps Wonder Woman on the ass in a fit of sexist entitlement. Wonder Woman is denied the ability to respond to the assault because of other matters that take precedence in the story. The story seems to be saying that there are some things more important that getting upset over some harmless slap and tickle. You can almost hear chants of “Let a man be a man! Stop trying to emasculate us!” in the subtext. The wonder, for me, is in how this scene was deemed acceptable and harmless to begin with.

I’m sure that to Brian Azzarello (the writer of the story) and most guys in general, it was all very innocent, designed to show us, through action, just what kind of rapscallion Orion is. No one asks, however, if there are other, less rape-y ways to convey the same point. I imagine most men don’t see the harm because men rarely have to be on the receiving end of these sorts of violations, which are products of rape culture. Largely, men don’t have to walk through creation tense and braced for anything in nature to leap out on them and sexually violate their bodies and spaces. One out of every six men aren’t raped. Ninety percent of rape victims aren’t men. Men’s bodies aren’t under the constant policing and legislation of other men. Don’t let the members of the “men’s rights” movement (yes, that’s an actual thing) hear you say this, though. Ruling every major institution on Earth apparently isn’t enough; men have to be considered innocent and absolved of every crime, too. Patriarchy is a helluva drug.

When you have the luxury and privilege of wielding massive amounts of institutional power, Wonder Woman getting slapped on the ass in a comic books seems like a silly thing to get worked up about. It doesn’t matter that this act is just the latest in a string of very clear hostilities toward the idea of female and feminine self-government and self-determination—hostilities that aren’t limited to comic books. I propose that this action isn’t harmless, not even when it happens in the funny pages. I believe depictions like these reinforce the idea that there are no limits on men’s behavior, particularly in relation to women’s bodies. If the most powerful woman in the universe can get slapped on the ass and all she gets to do in response is get angry and, generally, live with the violation, men’s power is reaffirmed and all is right with the universe.

Except that it isn’t right.

I made another crucial error: I posted my feelings on a comic book message board. Not known for their cultural or political sensitivities, many comic book message boards are merely echo chambers in which people who are, by and large, sycophants gather to reinforce each other’s narrow-mindedness and reflect each other’s images at twice their actual size (to paraphrase Virginia Woolf). The audience, at least by way of message boards and comments sections, is remarkably repetitive when faced with sociopolitical criticism about the stuff they love: first defense, then denial, then a hyper “rational” analysis of why there couldn’t possibly be any misogyny/racism/sexism/homophobia in their beloved art form. They insist that the problem lies with the observer not with the object being observed. Dwayne McDuffie, rest his soul, had this audience pegged.

My comments were met, mostly, with simmering rage or the aforementioned cognitive dissonance: “Let me explain this to you rationally: I’m not a bigot and I like this book. So this book couldn’t possibly be bigoted in any way.” Anyone who agreed with my commentary was summarily dismissed, talked over, or explained away.

And, of course, there’s the tried-and-true option of dragging out the token members of the audience, the few blacks or women or queer people in the ranks who support the status quo. Nothing says “conversation ender” like, “Well, I have a female friend who said it was okay. So it’s not misogynist.” As though institutional pathologies like misogyny, racism, or homophobia require that every member of the oppressed class sign off on its identification; as though members of oppressed classes don’t succumb to the psychological warfare that is bigotry and participate in and perpetuate ideologies that are harmful to them and others in their social group; as though the oppressed don’t sometimes identify with the oppressors. Stockholm syndrome is very real.

I’ll agree that the problem lies within the observer (only not the observer the aforementioned audience believes), but the problem also lies within the object being observed. The reason why this audience doesn’t perceive any harm, intentional or otherwise, is because the creators, institutions, and this audience are literally speaking the same language. White supremacy isn’t white supremacy amongst white supremacists; it’s reality. Misogyny isn’t misogyny amongst misogynists; it’s normalcy. Homophobia isn’t homophobia to homophobes; it’s just the way God intended things. It’s very difficult for anyone inside a giant circle to have the necessary perspective to perceive its full shape.

There’s a reason relatively few women, black people, or openly queer people are employed in the mainstream comic book industry or hold relatively few positions of power within the institutions that distribute them. There’s a reason why those who are employed there have to do much to tamp down any perceived differences in opinion or worldview and get on board with the straight white male status quo. It has nothing to do with women, black people, or queer people not being talented enough to compete or there not being enough them present in the potential talent pool. It has everything to do with already being friends with an influential straight white guy at the company. It has everything to do with a group of frightened individuals setting up shop in their citadel, trying desperately to fortify their tower of straight white male hegemony in a world where that hegemony is becoming decidedly less tenable.

And you don’t only see this happening in the comic book industry. You see it in mainstream politics as well with organizations like the GOP trying to decide if they should jettison some of their more outrageous, overt bigotries in order to court enough Latinos, women, and gays to win elections. It reads to me as a sort of panic, a sort of regrouping of the straight white guard as they try to figure out what it means to be straight, white, and male in a world where queer people are demanding civil rights, a black man is the leader of democracy, and women are asserting control over their own bodies.

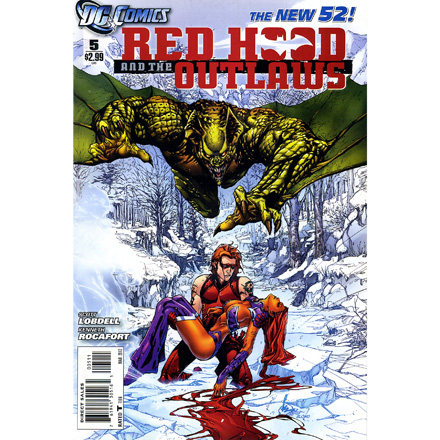

One of the ways in which they think they can reclaim the power they believe they’ve lost is through media propaganda. Since Obama’s re-election in 2008, for example, we’ve seen the incredible return of overt racist paradigms like the white savior and black pathology, as well as the puzzling return of 1950s values in relation to feminism post-Sarah Palin—not just in the real world, but in entertainment media as well: Did you miss World’s Finest #7, where Power Girl decided she knew everything she needed to know about African nations and their child soldiers because she watched KONY 2012? Or what about Miles Morales in Ultimate Spider-Man, who was not only at odds with his criminal uncle, but has to hide his identity from his ex-con father, too? Because, you know, nothing says “black” like criminal pathology. And don’t get me started on Bunker in Teen Titans, the gay Mexican character whose power is, wait for it: creating purple energy bricks. Purple. Bricks. I couldn’t create that big of a stereotype even if I tried really hard. But for some folks, it’s apparently rather easy.

We’ve seen these corporations pay lip service to diversity, but it’s always diversity for diversity’s sake—that is, diversity because they think it makes them look cool and hip in multicultural spaces. But bigots don’t understand the difference between diversity and tokenism, nor do they recognize diversity as something beneficial to themselves. They don’t see it as something that can open them and their organizations up to new ideas, new audiences, and new ways of being. They always regard the concept of diversity suspiciously, as something forced upon them, a notion that tries to coerce them into being politically correct, a practice the makes them, against their will, admit into their ranks “unqualified” people who didn’t “earn” their spot (because, you know, being a popular writer’s friend is considered earning a spot).

When called out on their nonsense, these corporations blame the bigotry on their audience: “Well, we tried to get this product featuring X Minority Figure off the ground, but the audience just wasn’t ready for it.” Bigots, unfortunately, have a collusive and mutually beneficial relationship that allows blame to be passed around (but never landing where it should), while keeping us distracted from the fact the structural impediments remain unmoved. And that’s all according to plan.

I’ve concluded that it’s useless to have these discussions with people whose fantasies rest on the fact that none of the social conventions upon which comic books stories are built can be seriously challenged or interrogated. It’s pointless to have these debates in this “post-racial” age where you’re only a racist if you use the n-word, you’re only a misogynist if you beat up women, and you’re not a homophobe, you’re just beholden to religious principles. Bigots—even passive, rational ones—are incredibly similar in their reaction to criticism: “My feelings are more important than your struggles.”

The only option left to individuals like myself who have had enough of the microaggressions and the chorus of defenders and deniers—who have had enough of the grating, tone-deaf depictions of women, people of color, and queer people in these often poorly written, poorly drawn, increasingly expensive books—is to opt out. And that decision is made evermore clear when you consider that the industry has been bigoted since its inception and you simply weren’t conscious enough to detect it when you were a kid. While the country has taken strides toward being a more perfect union, the mainstream comic book industry has, for the most part, dug its heels in and refused to move.

So I admit defeat. I am, ironically, waving the white flag. The bigots win. I’m plum tuckered out. I don’t have the energy to fight anymore. I say if they like the comic book industry and its product just the way they are, faults and all, let them have it. As long as I don’t ever have to read a misogynist Wonder Woman story or a racist Spider-Man story or a Superman story told by a homophobic extremist ever again, it’s all good. There are better products to spend my money on. That the mainstream comic book industry doesn’t want my money for fear of alienating their core audience of bubble blowers is the fault of their bad business model, not mine. In the meantime, I’ll be over here reading novels digitally on my iPad. These works, at least, reflect the world as it is, as it could be, as it should be, rather than as some defective, reductive supremacist fantasy.

__________

Robert Jones, Jr. is a writer/editor from Brooklyn, New York and creator of the Son of Baldwin blog. He is currently working on his first novel.