(or “Can Manga Muster Up Its Maus / Watchmen Mega-Crossover Hit?”)

As a reader of Hooded Utilitarian, you’re probably a little like me: you spend so much time in the world of comics and manga, you’re a little weirded out when you remember that the vast majority of readers in America still think that “comics are for kids.” Why do you think there are still magazine / newspaper / TV news reporters who trot out that tired headline “Pow! Zap! Comics Aren’t For Kids Anymore?” It’s because it’s news to them that there are lots of comics (ahem, “graphic novels”) that are written by grown-ups, for grown-up sensibilities.

Even now, if I mention that I read graphic novels to my friends, co-workers, family members and acquaintances who are non-comics readers (there are a lot of them), only 1-in-5 (maybe 1-in-10) will mention that they’ve read and enjoyed a graphic novel. They’ll usually name-check Maus by Art Spiegelman, or maybe Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. But it’s extremely rare that I’ll hear a manga title mentioned in this short list of grown-up graphic novels that reach non-comics readers. That’s really a shame, because manga has a lot of variety, and a lot of original and fascinating stories to offer to readers who normally shy away from superhero fare.

MANGA ABOUT ALMOST ANYTHING FOR ALMOST EVERYONE

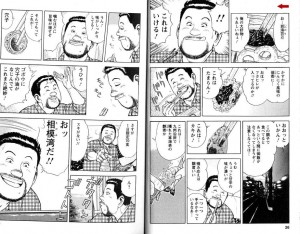

I love lots of things about manga, but there’s one thing I especially love: it’s so incredibly diverse. There’s manga about almost any subject you can imagine. There’s manga written by and for men AND women. There are stories for adults, teens, tweens, girls and boys — almost any reader of any age, and about almost any subject under the sun. This year alone, I’ve read manga about:

- Cats, dogs, fish, rabbits, dinosaurs

- Cooking, wine, bacteria and fermentation

- Basketball, football, ice skating, mountain climbing

- Rock music, classical music, kabuki, acting, ballet

- Fine art and fashion

- Space exploration, astral projection, oceanography, medicine, religion

- Autism, alcoholism, drug abuse, homelessness, serial killers

- English maids, Spanish bullfighters, Turkish nomads

- Gay, straight, cross-dressing, transgendered and transsexual characters

- Single parents, office workers, soldiers, librarians, pastry chefs

- …Even comics about making comics!

And that’s mostly just the manga I’ve read in English. If we open it up to manga that’s available in Japan, the variety of stories and styles is even greater.

Really great manga creators draw about subjects that they’re passionate about – and their enthusiasm, diverse art styles and points of view make their comics a joy to read. “Manga” is not a style – it’s a genre, just like “rock music” is a genre that can be expressed in a variety of ways for a variety of audiences.

So why do people have such a narrow perception of what manga is? As Ed Chavez mentioned in his essay, in Japan, “manga” just means “comics.” I say we need to think beyond that. In North America, calling manga “comics” limits a book’s appeal to just comics readers. Calling it “comics” forces a book to try to overcome what mainstream book readers assume “comics” are – they think comics are kids stuff.

TOO MUCH OF A GOOD THING: FIGHTING FOR COMICS FANS’ ATTENTION

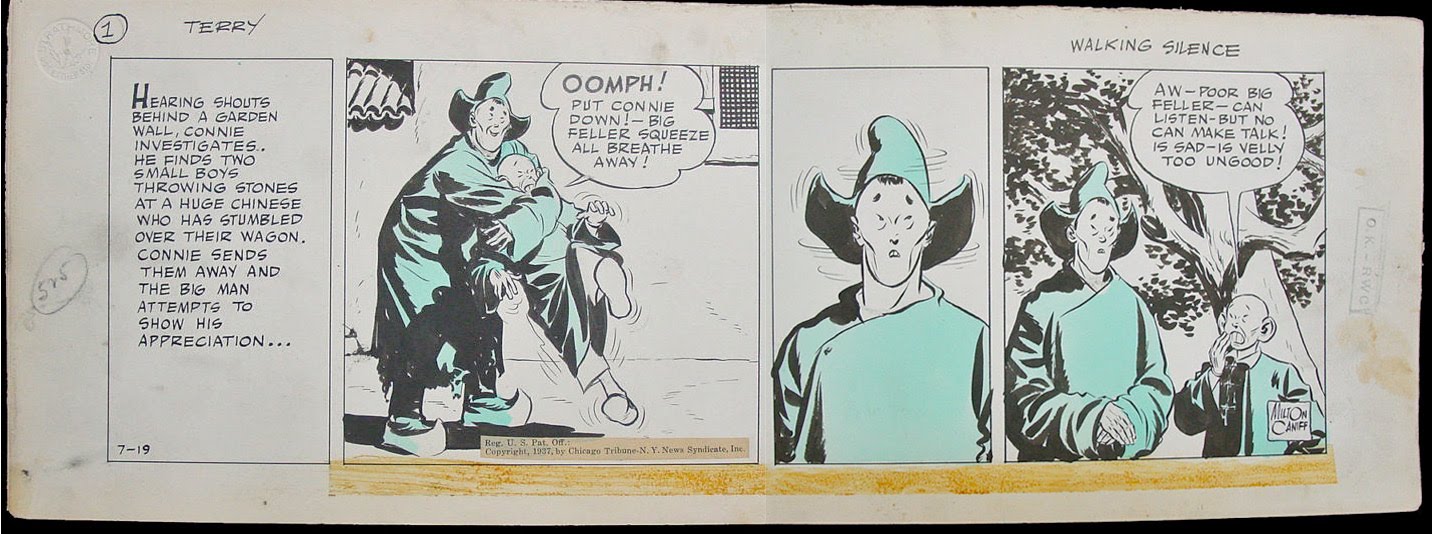

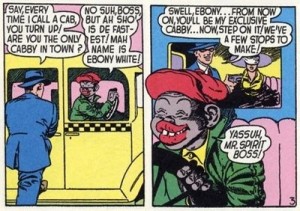

If American comics have to deal with the “comics are for kids” stigma, imagine what manga has to endure. Not only does manga in America have to deal with the “kids stuff” label, it also has to fend off assumptions held by mainstream comic book readers.

“Manga? Isn’t that girly stuff?”

“Manga? What, like Pokemon?”

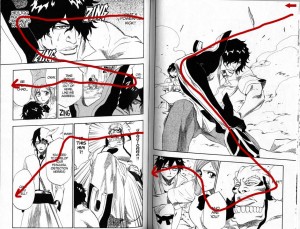

“Manga? I can’t read that backwards crap.”

“Manga? Nah, I’m not into tentacle porn.”

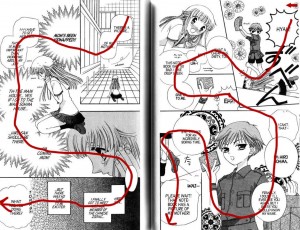

As things stand now, a lot of manga that’s published in the U.S. is geared to appeal to people who already “get”manga: the fans who watch anime, or have already been introduced to the joys of manga, via the classic”gateway drug” manga titles like Akira, Lone Wolf and Cub, Fruits Basket, Naruto, Death Note and Ranma ½. But by focusing on the already “converted,” are we missing out on an opportunity to reach out beyond the comics shop, the manga aisle or even the “graphic novels” section of the bookstore?

Where there was once only a handful of manga titles published in the U.S., there are now hundreds – and a lot of them are targeted at teen readers. As a result, a lot of teen manga fans are overloaded with choices. There’s so much great manga for them to choose from nowadays, they despair because they can’t afford to buy everything they want to read. So faced with so many desirable titles, what do budget-strapped manga readers do? Some (okay, lots of) fans download it for free by any means necessary (Erica Friedman dove into the scanlation issue in her essay for this roundtable).

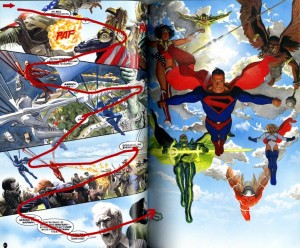

Meanwhile, on the other side of the comics shop, a lot of diehard superhero comics fans have a hard enough time keeping up the various crises on Infinite Earths, Darkest Nights, Brightest Days and Marvel zombie invasions. Why would they invest their spare time sifting through the hundreds of similar-looking manga on the shelf to find one that they might enjoy reading, much less consider buying, with their already tapped-out comics-buying budget?

These clichés of comics fans have tons of manga / comics titles fighting for their attention and their dollars. So why bother trying so hard to sell “arty,” “indie” or “grown-up” manga to this crowd? I say think bigger – and think outside the comic shop.

LET GO OF LABELS THAT LIMIT MANGA’S APPEAL TO NEW READERS

To break out of the comic shop/manga aisle “walled garden”, we need to stop focusing on selling this kind of comics for grown-ups merely as “manga” (or “seinen manga,” “josei manga” or even “indie manga”). Clinging to Japanese classifications may give a diehard fan a degree of satisfaction that they know that a particular manga was published in XYZ magazine in Japan, but classifying a particular manga title as a “shojo,” “shonen,” or “seinen” title isn’t all that helpful to a reader who doesn’t understand Japanese; it just adds another potentially off-putting “code word” for new readers to decipher.

Using Japanese labels to describe a book tells new readers that they have to take Japanese lessons or earn their “otaku cred” before they’ll be allowed into the “manga clubhouse.” As Shaenon Garrity pointed out, and as Ryan Sands also mentioned in his essay, what we consider to be “indie” in the U.S. doesn’t always jibe with how Japanese readers perceive the same series anyway.

Trying to sell manga based on how they were sold in Japan can cut off worthwhile books from the readers who might potentially appreciate them most. For example: Emma by Kaoru Mori is an exquisitely-drawn, painstakingly-researched, beautifully-told historical romance. It was first published in Comics Beam, an eclectic “seinen” or “mens'” manga magazine. Based on its romantic storyline, Emma was marketed in the U.S. as a “shojo” or girl’s manga series. Naturally, its “girly” look and subject led a lot of “sophisticated” comics readers to turn up their nose at this series. Although it was submitted for consideration, it was snubbed for the 2010 Eisner Awards.

That’s a shame, because I’d argue that Kaoru Mori is probably right up there as one of the world’s true masters of graphic storytelling. Her ability to capture nuances of character, emotion and relationships with just a few strokes of her pen is astonishing. Mori’s current series Otoyomegatari (The Bride’s Stories), which is as yet unlicensed in the U.S., has one of the most stunning, heart-pounding hunting scenes I’ve ever seen in print.

Why should anyone who loves comics deny themselves the pleasure of reading such a wonderfully-drawn, masterfully-told story just because it looks “girly” or (gasp) just because they have a thing against what they think “manga” is?

EXPOSING MANGA TO NON-MANGA READERS

Breaking out of the mainstream mindset that “all manga is Naruto” requires savvy and imaginative marketing on the part of U.S. manga publishers.

Manga is incredibly diverse. Selling every manga title with a “one size fits all” approach to readers is a grave disservice to these comics, and it limits their potential readership. I know it’s time-consuming to do so, but it’s probably more effective to sell graphic novels to various types of readers based on the various titles’ individual art styles and subject matter.

If we can’t get new readers into the manga section, then it’s up to us, publishers and people who want to see more “grown-up” manga get the attention it deserves, to put manga in front of new readers by bringing manga to where these prospective readers are getting information now: non-comics magazines, newspapers, blogs, TV shows, radio shows – anywhere they turned on to new ideas. One way to do this is to focus on the subject and style of the manga, and as Brigid Alverson suggests in her essay, pitch these unconventional graphic novels to non-comics media outlets.

While rare, several manga titles have gotten some attention from non-comics media:

- Basketball manga by Takehiko Inoue (Real and Slam Dunk) was reviewed and Inoue was profiled in the L.A. Times during the Lakers – Celtics NBA Finals.

- Kami no Shizuku (Drops of God) by Tadashi Agai (a.k.a. brother/sister team Yuko and Shin Kibayashi) has been written up in the New York Times, CNN and Decanter Magazine, and wine blogs. Alas, while it has been published in French, it’s not yet licensed in English.

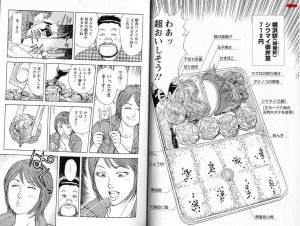

- Oishinbo has been featured in the pages of Bon Appetit, the food section in several newspapers and numerous food blogs. As a result, I’ve seen Oishinbo sold at cooking specialty shops like Omnivore Books in San Francisco and Good Egg in Toronto. Seven volumes of Oishinbo, each focused on a different food, are available from VIZ Media.

- LA Weekly columnist Liz Ohanesian regularly writes about anime and manga culture with a hip, street-smart voice and perspective that’s not just “otakus writing for otakus” – check out her fab article about former Bratmobile singer Alison Wolfe’s role in localizing Ai Yazawa’s rock ‘n’ roll drama, Nana.

- Whitney Matheson, from USA Today’s Pop Candy blog gave a shoutout to Detroit Metal City, Kiminori Wakasugi’s crass, brash and outrageous heavy metal comedy – and even named it as one of the top 10 best graphic novels of 2009, along with A Drifting Life and Oishinbo

- Summit of the Gods by Jiro Taniguchi, a manga about climbing Mount Everest got a nice write-up in Outside Magazine. (Available from Fanfare-Ponent Mon)

- Section Chief Kosaku Shima, one of the most popular “business manga” titles in Japan was written up in The Economist. Unfortunately, only a few volumes of the Kodansha bilingual edition of this series is available in English.

- With the Light by Keiko Tobe, a series from Yen Press about a young mother’s struggles to understand and raise her autistic son has been featured on a few autism-focused parenting blogs.

- GoGo Monster by Taiyo Matsumoto (VIZ Media) was nominated for the L.A. Times Book Prize alongside Asterios Polyp, Scott Pilgrim, and Footnotes in Gaza.

- Ooku by Fumi Yoshinaga (VIZ Media), won the 2009 James Tiptree Jr. Literary Award – an “annual literary prize for science fiction or fantasy that expands or explores our understanding of gender.” Ooku certainly fit the bill, as it examines an alternate reality where most of Japan’s male population has succumbed to a mysterious plague, and the shogun is a woman.

Meanwhile in Japan, manga is featured in fashion magazines, alongside fashion photo spreads and celebrity interviews:

- Manga creator Erica Sakurazawa (The Aromatic Bitters from TokyoPop) recently did a 6-page short story adapting the characters of Sex in the City as manga characters. This full-color comic was featured in the Japanese edition of Harper’s Bazaar as a showcase for both the Sex and the City 2 movie and the latest styles by Louis Vuitton, Prada and Versace.

- Ai Yazawa’s Paradise Kiss (TokyoPop), a story about an aspiring model and fashion design students, was serialized in the pages of Zipper, a fashion magazine.

As Kate Dacey asked in her essay, why aren’t we doing more to reach the one audience that the U.S. comics industry has been ignoring or failing to reach for years: young women? If we can have manga versions of Twilight and Gossip Girl, why not Sex and the City comics? Why isn’t a series like Suppli, a series about the professional and romantic tribulations of a young woman working at an advertising agency reviewed or serialized in Glamour or Marie Claire? Why not have Bunny Drop, a completely relatable series about a single father and his young adopted daughter discussed in parenting blogs or magazines? And what if (as Shaenon Garrity suggested in her essay) Oprah actually plugged a manga series on her show or magazine? The mind boggles.

WHAT WILL IT TAKE TO TAKE IT TO THE NEXT LEVEL?

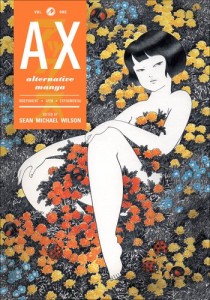

There are so many possibilities out there to explore. I’d love to see a regular columns about indie manga – or even have have manga featured more prominently in hip, artsy and pop-culture savvy magazines like Giant Robot, Hi-Fructose, Spin, Juxtapoz and VICE. Artistically edgy, smart and witty titles like Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu (Last Gasp), AX: Alternative Manga (Top Shelf) and I’ll Give It My All… Tomorrow (VIZ Media) are all appealing choices for these magazines’ readers.

Websites like SigIkki.com make it easy for new readers to sample manga online before they buy them; it’s a painless way to turn new readers onto manga they might not ordinarily be exposed to. It can only get better as more manga is available for sampling and reading online or for download via eBook readers like the Kindle or iPad.

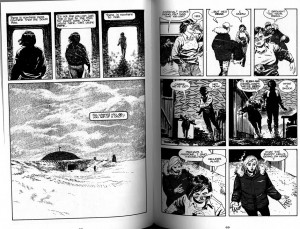

It’ll take a lot of effort and outreach to get to the point where we have a manga title that’s as widely read as Maus or Watchmen. It won’t be easy. Books like that achieve a high level of attention and acclaim because they have a rare combination of factors going for them:

- a great story that’s well-written, enjoyable to read and accessible enough to captivate even non-manga/non-comics readers

- strong and consistent marketing support from publishers and creators

- lots of great word of mouth from readers.

One only needs to look at the attention and care that Drawn and Quarterly put into promoting the work of Yoshihiro Tatsumi to see how it could be done. There are lots of good reasons why A Drifting Life made it onto more “Best of 2009” lists than any other manga title put out last year (It’s just an amazing book, period) – but I’d have to say that D&Q’s thoughtful and consistent marketing efforts made a huge difference too.

I think that manga’s version of the Maus/Watchmen “cross-over hit” will happen eventually – but it won’t if we content ourselves with just promoting manga to the already converted.

I believe in putting my money where my mouth is, so on a 1:1 basis, I recommend manga to friends based on their interests.

- I gave a copy of Kami no Shizuku to a sommelier pal (he actually heard about it from the Decanter article, and he found it to be completely fascinating).

- I’ve given copies of Solanin, GoGo Monster and Children of the Sea to friends who normally just read “indie” comics (they’ve come back to me asking for more recommendations).

- I’ve turned on girlfriends to Emma just by describing it as being like a Merchant-Ivory film, or similar to Jane Austen books.

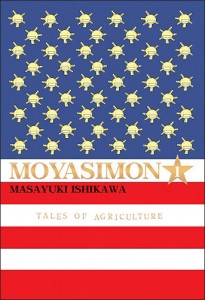

- I gave Moyasimon: Tales of Agriculture (Del Rey Manga) to a friend who is a technical editor who writes about waste-water management (she’s always asking me when the next volume will be coming out).

- My cat-loving sister who hasn’t read a comic book since she stopped reading Archie comics 30 years ago is loving Chi’s Sweet Home by Konami Konata (Vertical).

- And I’m pretty stoked at the reaction I’ve gotten when I’ve recommended Biomega to this particular friend.

So I’m doing my part – what are you doing to turn on new readers to manga that they might enjoy? Try it – you might be pleasantly surprised by the results.

______________

Update by Noah: The entire Komikusu roundtable is here.