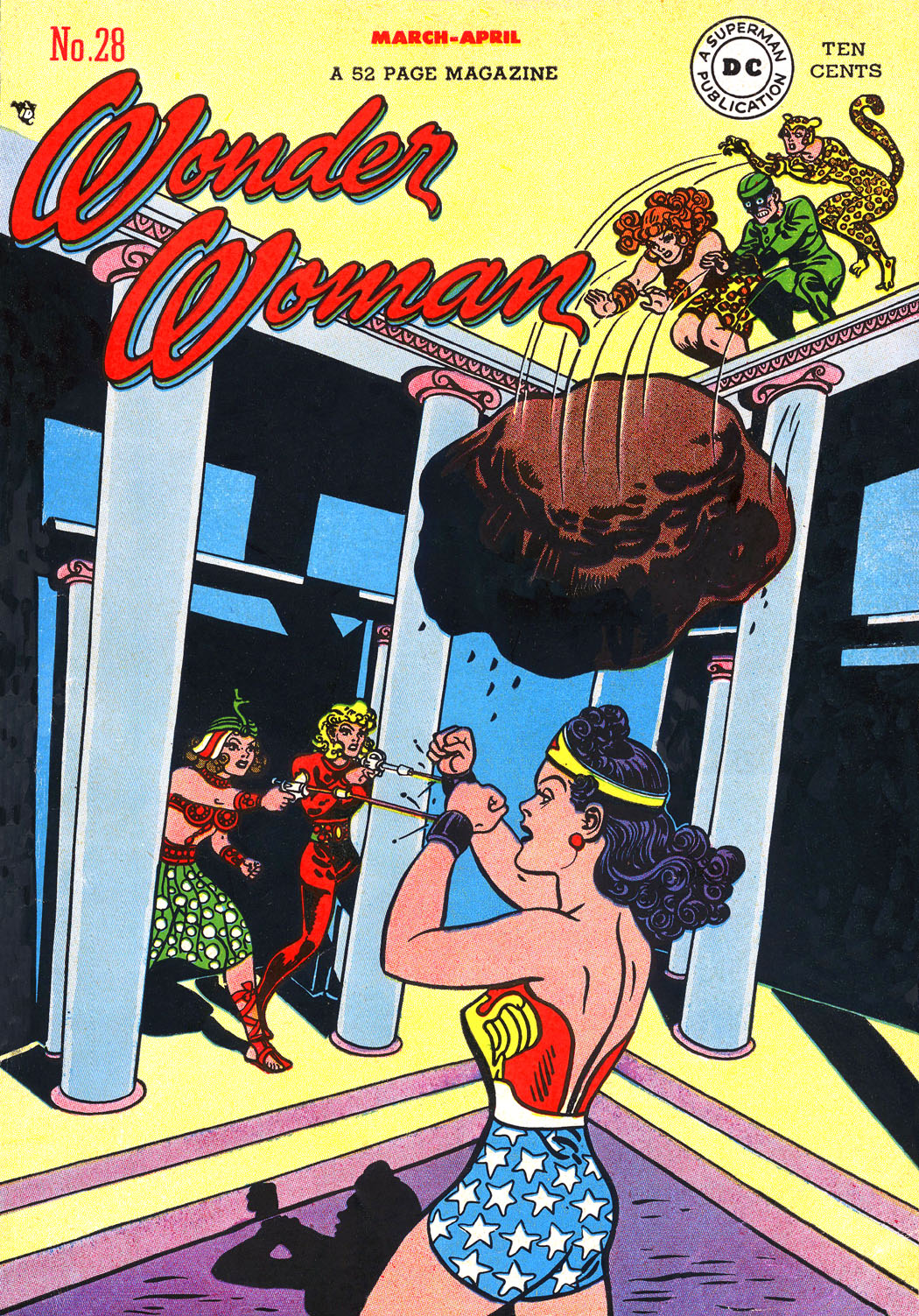

This is part of a roundtable on Marston/Peter’s Wonder Woman #28. The roundtable index is here.

_______________________

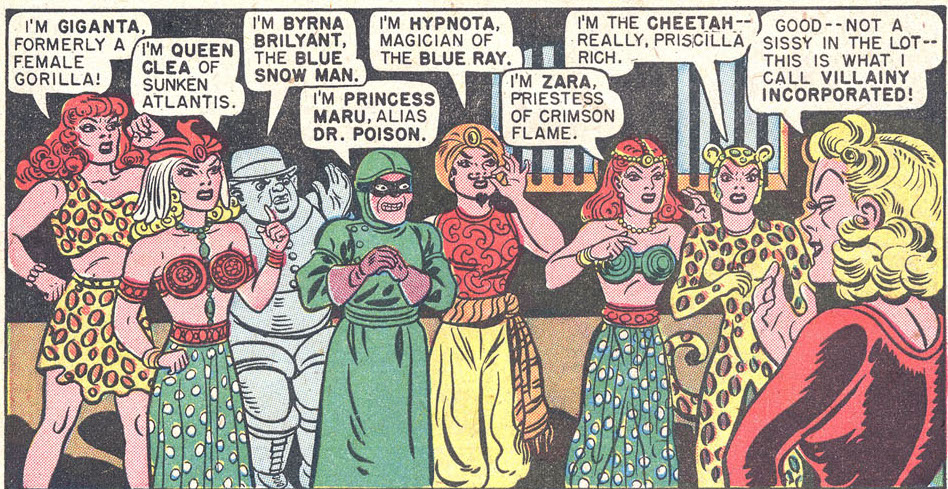

Wonder Woman #28 is a great example of the Marston-Peter team at its most gloriously over-the-top. A group of prisoners on Transformation Island, the Paradise Island reformatory, escape and spend thirty-six pages trying to destroy Wonder Woman, Queen Hippolyta, the Amazons, and Wonder Woman’s sidekicks, the Holliday Girls, only to be (of course) foiled at the end by everybody’s favorite Amazon. The prisoners are a piece of work: almost half of them are drag kings. One of them is an evil snowman.

Could anyone get away with using such wacky characters today? Maybe. In the 1990s, John Byrne resurrected Egg Fu, not only wacky but racist to boot, and got away with it. Personally, I love the beautiful villains — and for the most part, Marston’s and Peter’s villainesses were beautiful — like Giganta, “formerly a gorilla.” In fancy bras and filmy skirts, they resembled a cross between Hollywood harem girls of the period, and all the beautiful but evil women on the cover of every science fiction pulp magazine. Queen Clea of Atlantis and Zara, priestess of the Crimson Flame, are dressed almost alike in outfits like that, except that one’s blonde and the other’s a comic book redhead, with crimson hair.

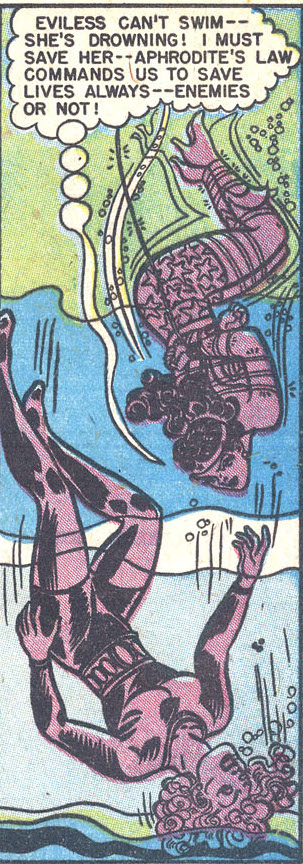

The plot is as wacky as the villains. Wonder Woman is forced to steal a submarine and tow it with her teeth. But she’s plucky and bounces back with a wisecrack: “You’re so kind, Clea!” Earlier, when the villains had chained the princess and her mother to a pillar with flaming chains, she had quipped, “What sweet girls you are!” Indeed, Wonder Woman rarely seems to be afraid for herself , perhaps because she knows she will win in the end. She fears for the other people in peril: her sister Amazons, the Holliday Girls, who have been shoved into a devolution machine and turned into gorillas, all except for their heads. She even fears for the villain mastermind, Eviless the Saturnian. Attempting to escape while tied to a boat full of villains, Diana pulls the boat under water. But Saturnians can’t swim! So Wonder Woman rescues her: “Aphrodite commands us to save lives always–enemies or not!”

And by the way, Steve Trevor, despite the fact that he always needs to be rescued by Wonder Woman, isn’t as wimpy as he’s been made out to be. When Cleo and Giganta tie him up and threaten to burn his eyes out and cut him to ribbons, he’s brave enough to quip, “You’re certainly playful girls! Go ahead and have your fun!”

And it is fun. You don’t take it seriously. The entire story is fun.

With a few exceptions, Wonder Woman hasn’t been fun for quite some time now, but you still don’t take it seriously. Gale Simone, in my opinion one of the two best Wonder Woman writers (The other is Bill Messner-Loeb) got into the spirit of the original when she gave the amazon princess white talking gorilla sidekicks, to take the place of Etta and the Holliday girls. They move in with her, and apologize for the “flinging incident.”

But more often, it seems that when the almost 100% male writers Wonder Woman has had get their hands on her, they just can’t wait to re-invent her. Sometimes the re-inventing is mild, if annoying, as when Wonder Woman’s suit keeps shrinking while her bust size increases. Depending on the artist, her hair bounces from curly to straight and back again. But sometimes it’s a very violent re-invention, as when in the late 1960s writer Denny O’Neill completely disempowered Princess Diana, removing her from both her powers and from Paradise Island, giving her a male guru (and a what a racist depiction that was!), taking off her iconic starry costume and garbing her in a white Emma Peel-style jumpsuit. The result was a story arc about a karate-using woman in a white jumpsuit with a male guru. What it was not was Wonder Woman.

J. Michael Straczynski gave Diana a wardrobe makeover again, in 2010, putting her into what looked like a 1980s disco outfit with long pants. Fans hated it and amazingly, DC Comics actually listened to them for a change, and restored the Amazon princess’ starry shorts.

And now it’s Brian Azzarello’s turn. He has taken everything that made Wonder Woman special, and done away with it, so that Wonder Woman isn’t special anymore. He can’t shove Princess Diana back into a white jumpsuit — been there, done that — so instead he destroys the Amazon’s very origins, which are as iconic as her star-spangled costume. As Prometheus made mankind out of clay, as the Navajo gods molded all the animals of the Earth from clay, as the supreme deity molds the first man from clay in Judeo-Christian and Islamic mythology, Queen Hippolyta molds her baby from clay. And as if this divine origin, which Wonder Woman shares with the first of all creatures, is not enough, Marston gives it a feminist twist: the goddess Aphrodite breaths life into the statue. Thus, little Diana has two mommies.

It is highly unlikely in Marston’s original version that her tribal sisters would sneer at her for her origins, as they do in Azzarello’s version, and call her “Clay.” In fact, according to the first issue of Marston’s Wonder Woman, Aphrodite originally molded the entire race of Amazons from clay, and breathed life into them.

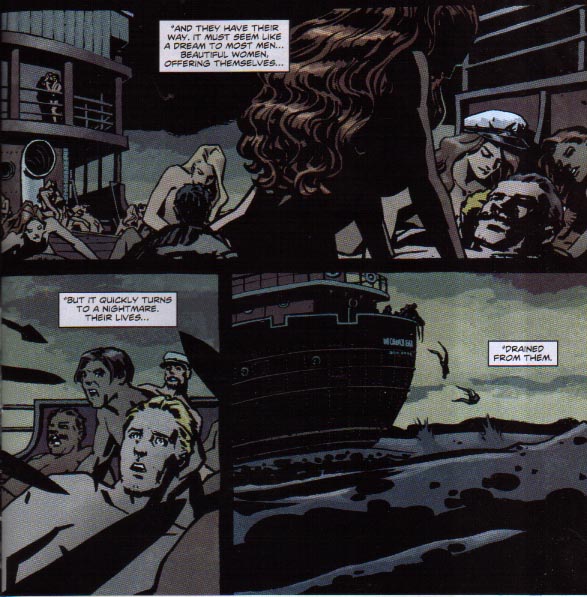

But Azzarello has taken care of that by demoting Wonder Woman, putting her at the end of a long line of mythic heroes fathered by Zeus, and of course, in taking away her feminist origins, making her a child of the patriarchy. And as for Diana originally being the only baby born on Paradise Island, Azzarello’s nouveau Amazons seduce sailors (and then dump the sailors overboard!), keep the girl babies that result from the union, thus keeping up their tribe’s population, and they sell the boys into slavery. Marston’s Amazons would never seduce or kill anybody, and they have no need to. They drink from a fountain of eternal youth, and as Hippolyta says, “Beauty and happiness are your birthright as long as you remain on Paradise Island.”

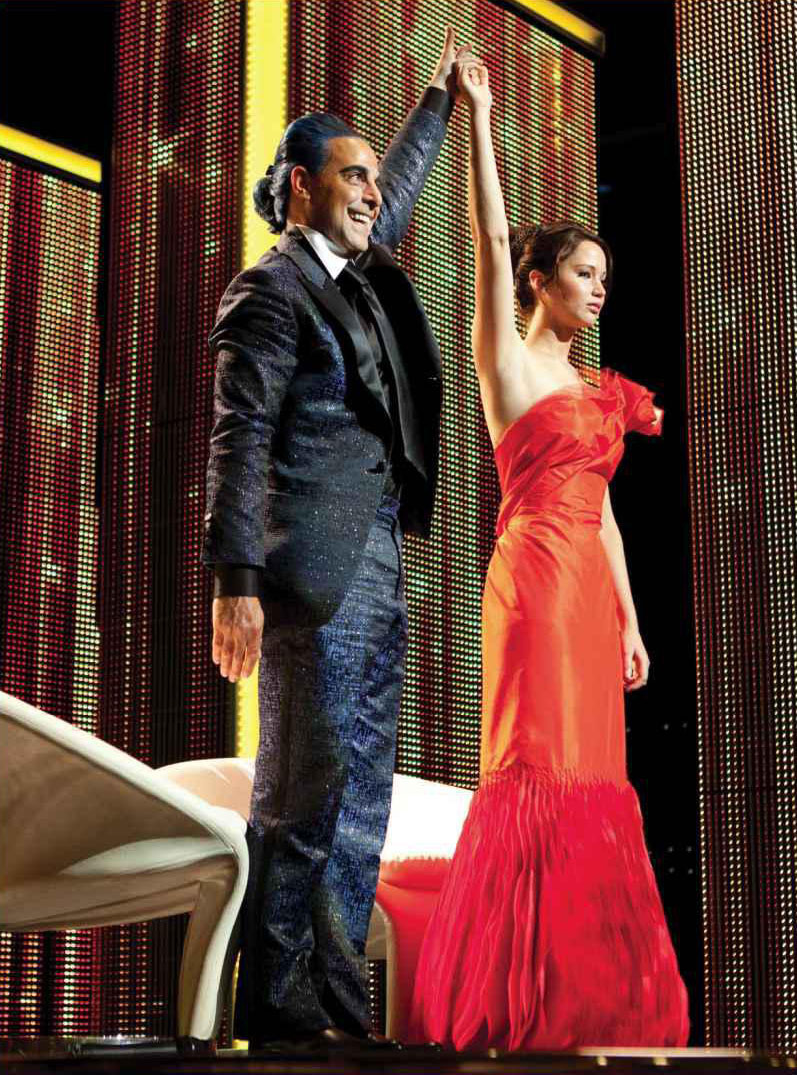

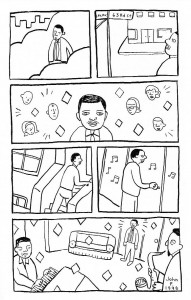

Azzarello/ChiangWonder Woman #7

This makes Diana’s sacrifice, when she leaves her island to go to “Man’s World” all the more poignant: she is giving up immortality in order to fight evil in a blighted land.

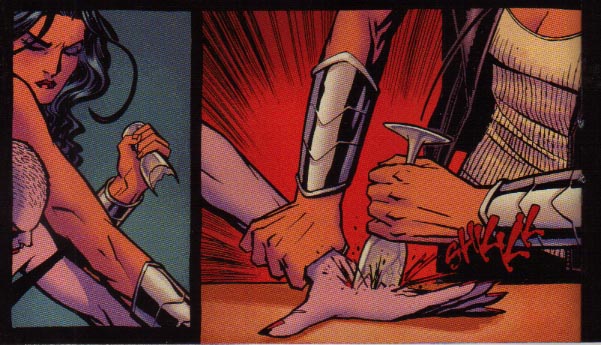

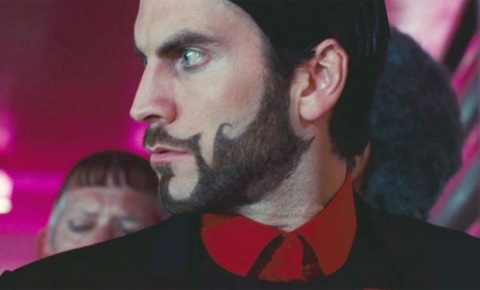

If Azzarello has demoted the Amazons to mean and ruthless killers, the gods have fared no better. Hera (Remember how Wonder Woman used to say “Great Hera?”) is now a soap opera-style bitch, a kind of Joan Collins dressed in nothing but a peacock cape. Her daughter Eris, the goddess of strife, is a bald anorexic crusty. The other gods look like London hipsters and have become ironic. Diana has no personality at all, and definitely utters no quips. The gods lead her around and show her stuff, and she reacts rather than acts. Her expression changes from a pout to a shout and back again. Diana, who, Jesus-like, gave up her immortality for mankind, has become so vicious that she stabs Eris’ hand with a broken wine glass.

Azzarello/ChiangWonder Woman #4

To many of us, including yours truly, the Amazon princess is almost real. Yet in our saner moments we have to admit that she is a construction, a thing of paper and ink who is a slave to anyone who writes her. Thank Hera for my reprints!