Hollywood loves dystopias. They’re blockbusters with brains – mass market morsels with box office potential just waiting for grad students and culture writers to dissect, contextualize, and elevate. Regardless of whether the movie is meant to be camp or self-serious, the stories and themes need to be as intricately drawn as the world creation of fantasy films and novels, yet still rooted in some recognizable reality. In the simplest, and perhaps most confusing of terms, a dystopia is the opposite of a utopia. Dystopias aren’t the same as post-apocalyptic anarchy. That might be the origin of the dystopia, but after the chaos comes control. In a dystopia, the miserable structures are institutionalized – whether by a government, a corporation, or technology.

On one level, dystopias are entirely artifice. Everything is manufactured and tightly controlled to support whatever claim the controlling force has given for its power, from language, to information, to material goods. Individuals are dehumanized, and uniformity reigns. But with all the deconstruction of the plots and themes and texts and Cave allegories, it’s easy to overlook how the films are styled to show the audience a new and bleak world. What might seem an afterthought can become one of the most important elements of telling the visual story, exposing informative elements and details of the society that’s been created. Along these lines, I’m most interested in how wardrobe choices can illuminate something crucial about the world of a film.

Or: what will we wear when everything turns to shit? And why does it matter?

Why, for example, do all of the characters in the “real world” of The Matrix have to wear thin, holey, ill-fitting sweaters? What, beyond its blatant gesture to noir, is the meaning or significance of Rick Dekard’s trench coat? Why do all of the clothes in Children of Men just look…normal? In this essay I want to examine the great costumes in Gattaca and The Hunger Games — two examples of films with particularly weird dystopian fashion — to suggest some ways to think about costumes in the broader context of Hollywood’s visions of Dystopia.

Just as there are half a dozen varieties of dystopias in films, the costumes are similarly varied. Broadly speaking costumes in these films tend to fit into three categories: minimalist, over-the-top gaudy and garish, or retro poverty. Even something as straightforward as minimalist clothes can mean different things in different films. In Los Angeles Plays Itself Thom Anderson notes that films like to put the bad guys in modernist homes. Though of course not the point of modernist designs, the starkness of the sleek minimalism can easily be manipulated to signify some sort of deranged obsession with the superficial. Perhaps the ubiquity of high design might make that jump more difficult today, but with the right tone and the introduction of a pre-established villain, the minimalist home itself becomes the opposite of the calm utopia it was intended to be. Instead, the home becomes sinister, vapid and empty, not only of furniture, but of tenderness and humanity too. In other words, the good guys are never as well dressed as the bad guys.

Andrew Niccol’s 1997 film Gattaca presents the audience with a “not-too-distant future” where potential is predetermined by genetics. Employment and educational opportunities and advancement are set from birth, and liberal eugenics are used to manipulate genes to ensure the best possible outcome for people before they are even born. In this world, there are the successful and there are the defective and there is no real in between. Your genes tell the only story that employers need to know. Ethan Hawke’s Vincent is one of the defectives, with a life projection of only 30 years due to a heart condition who uses the black market to assume the identity of a genetically ideal person in order to become an astronaut.

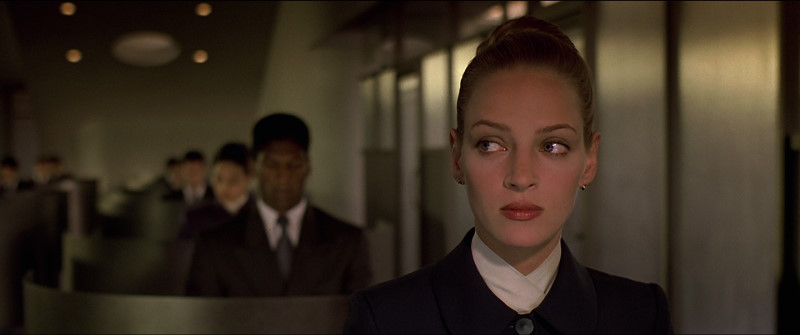

The clothes in the world of the genetically superior are sleek, modern, and minimalist. The men wear impeccably tailored suits, All of the colors are either dark or neutral. Men and women wear their hair slicked back neatly and tightly. At the highest level of genetic perfection, and correspondingly prestigious places of employ, everything is pressed and starched. The white cotton shirts that peek out of the somewhat androgynous suits are flawless. In essence, no individuality needs to be shown through the clothing, because anything that you’d ever need to learn about a person you could learn through a simple gene report. Though we never find out where the mandates for these sorts of clothes originate, it would be reasonable to think that it likely started with the government or a corporation. In Gattaca, individual agency is rare. But the clothes represent an implicit acceptance of the world that they’re in – the shame of their flaws and individuality are so deeply ingrained in all of the characters that a different way of life and dress likely does not even occur to them. Even Jude Law’s crippled Jerome who doesn’t leave his home dresses in bespoke suits and vests.

Those outside of this top echelon still dress in muted colors, but the outfits are ever so slightly more rumpled. The cops and private investigators sport noir like Fedoras and unassuming suits. Those at the lowest level, the janitors, wear uniforms too. Everyone has their place, and every place has its predictable dress. No one would be mistaken as being part of an elevated status. Genetic makeup and class are intertwined.

There’s a brief suggestion of subversion when Uma Thurman’s Irene goes out for the night with her hair down and wavy, in a form fitting gold sequin gown. In this scene she even acknowledges that the pianist that they’re watching couldn’t play as beautifully as he does without his flaw (extra fingers). Perhaps the wild hair and seductive gown represent individuality peeking through outside of the workplace. But the shame permeates the night off too. Work, perfection, and the company define and shackle our characters, and it’s where this otherwise “perfect” society starts to crack. Though it might be beneficial for insurance agencies and companies to know the exact genetic potential of all of its employees, once genetic discrimination becomes institutionalized, leaving no room for individual advancement or self-betterment, the individuals begin to falter. Jude Law’s character commits sucidie after realizing that his life in a wheelchair in this society is no life at all. Afraid of their own humanity and fearful of flaws, the characters resign themselves to the standards of their own society, reinforced by dress and presentation. It’s not an injustice, it’s just the way things are. Ethan Hawke’s character subverts the system only for his individual gain by conforming to its expectations – altering himself to meet their demands and exfoliating away as much of himself as possible.

Gary Ross’s adaptation of The Hunger Games is somewhat more simplistic and ultimately more frustrating. In this post-revolution world, there are the haves and the have nots and material goods are the only determinant. In the movie we get no explanation as to why the society is divided as it is. Why do the people in the Capitol get to be there? Intelligence? Money? Birth? Maybe it doesn’t matter. Much has already been made about the disappointment that some avid fans of the book felt upon seeing some of the film’s representations of the costumes, but for our purposes we’re only going to talk about what we actually saw on screen in light of what the movie tells us about the world.

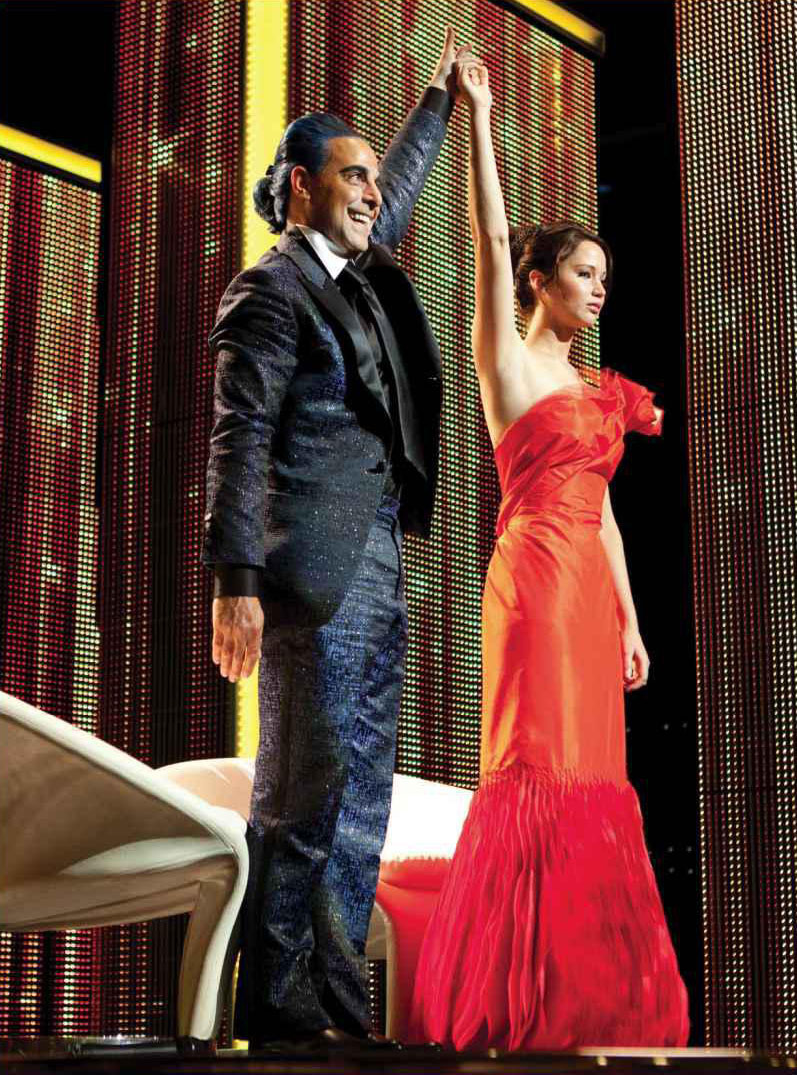

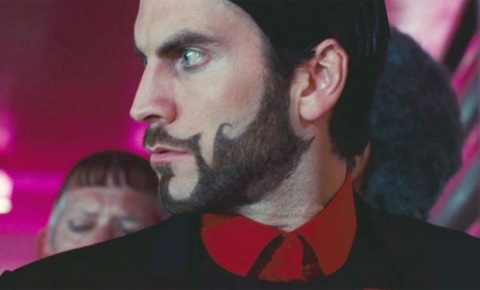

Those in the Capitol dress in lavish and gaudy clothes, reeking of invasive and discriminating excess that suggests both Marie Antoinette and a 1980s Wall Street Banker. The ladies wear puffy sleeves, full faces of white makeup, 1920s bee-stung lips, and neon shade of hair color. The men wear sparkly suits and facial hair so intricate that it resembles a tattoo. Grooming and appearance are clearly of great importance in the Capitol and everyone who resides there has both the money and the time to execute these looks daily.

In contrast, Katniss’s mining town of District 12 looks straight out of Harding-era West Virginia coal towns, with the earthy colored trousers and suspenders for the men, and modest knee length, short sleeved cotton dresses for the women. Makeup is non-existent, hair color is natural, and faces are smeared with soot. This is supposed to be a desperate people. Putting the citizens of District 12 in frocks that look like they were transported from The Great Depression could be a way to keep morale down. Not only do they have to lead miserable, impoverished lives, but they don’t even get any updated poverty clothes. It’s likely this was just an affectation of the movie, though, trying to make poverty look prettier thanks to the blinding revisionism of a style of clothes almost 100 years old.

Excusing the poverty porn of District 12, the initial division is striking. The contrast between Katniss in her drab blue dress and Effie in her magenta power suit sharing the same stage perfectly conveys the vast wealth disparity. Effie has everything, and Katniss has nothing. But once the film moves forward, and the tributes are transported to the capitol, things become less coherent. After examining the controlled and limited options for dress in Gattaca, The Hunger Games looks like it is verging on potential anarchy already. The varieties of dress are just too great. Everyone in the Capitol is so loudly individualistic, authoritarian control is hard to reconcile. But perhaps this is where The Hunger Games is a bold departure from the Gattaca-like uniformity. The control and the power is so pleasing to folks in the Capitol that they are willing to support the state since it allows them a superficial leniency in dress and decoration.

The makeovers for the tributes, though, seem inconsequential to the society in the movie. It’s all for show and entertainment and essentially looks like little more than fattening the pig before the slaughter, and has little to do with the power structures in place. Perhaps the fire costume was indeed more subversive in the books, but in the filmed adaptation it was more difficult to find the significance.

We could assume that the effeminate clothes and seemingly relaxed gender standards in The Capitol represent the government’s half hearted way of convincing those privileged enough to live there that they are indeed part of a liberal society. But when we step back and look at the evil oppressors in The Capitol as those in the districts might, it seems a strange choice on the part of the author and filmmaker to dress the bad guys effeminately. Is the point to just scoff at the excess and stop there, or is there something inherently dangerous in equating gay identity with the immorality of The Capitol? It becomes even more problematic considering the fact that beyond the suggestive clothes and makeup, we don’t see any sort of realized gay identity on screen – things are aggressively heteronormative. The ambiguity of the purpose of putting the bad guys in effeminate clothing ends up hurting the story, because it shouldn’t be a question that we have to ask, and it is irresponsible to leave it to unclear.

There are many other films to investigate. Sometimes clothes are just clothes, but in these dystopian films, they can be as meaningful and telling as a working knowledge of Huxley and Plato, even when the choices don’t quite seem to work.